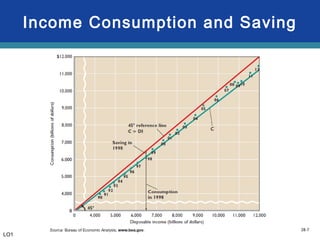

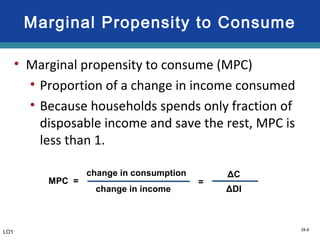

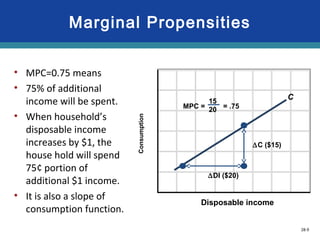

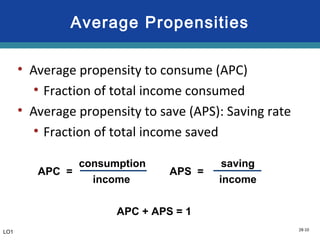

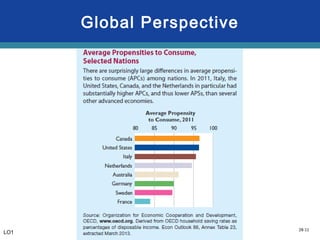

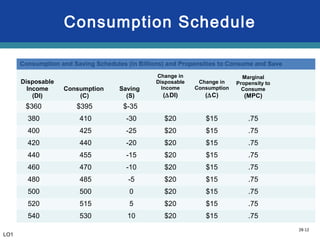

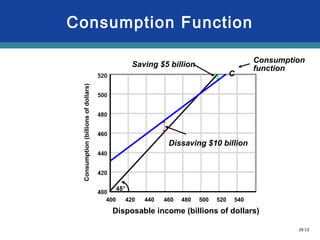

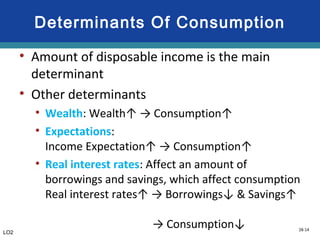

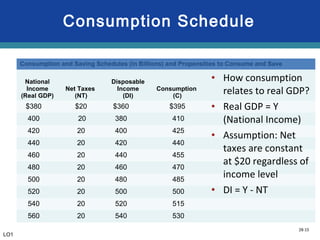

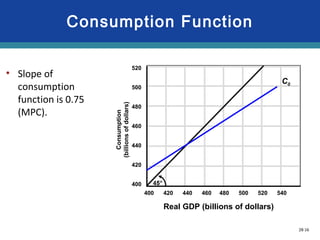

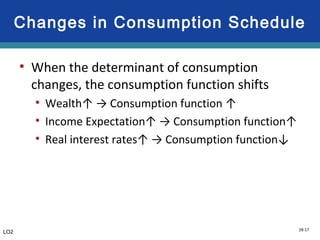

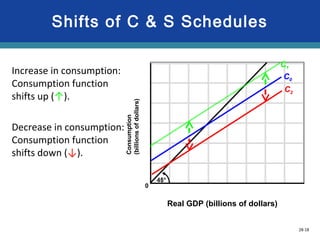

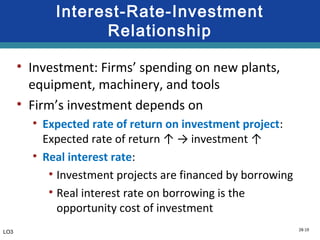

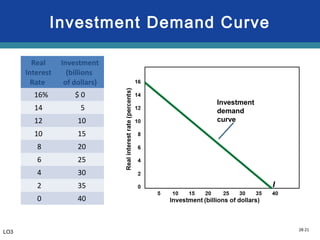

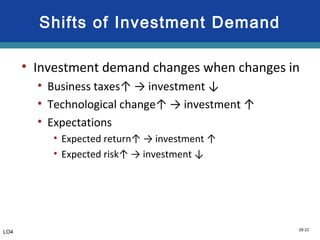

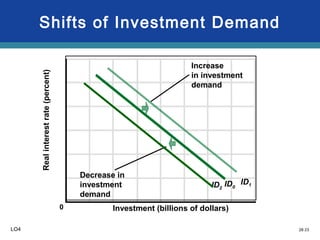

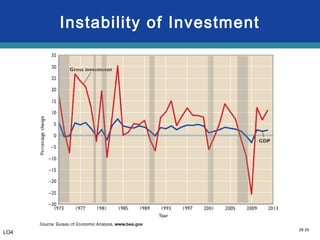

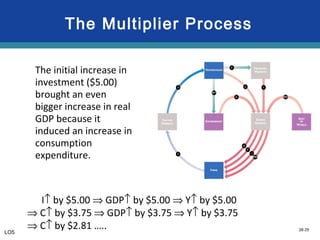

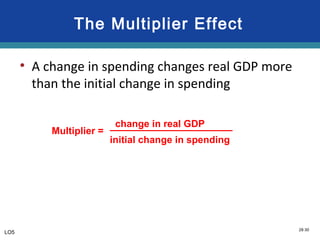

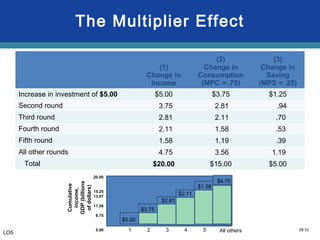

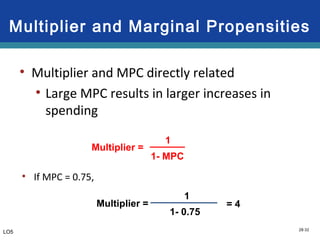

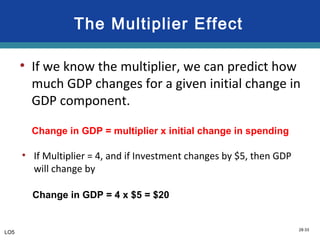

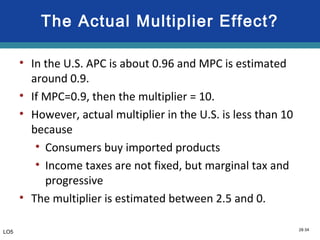

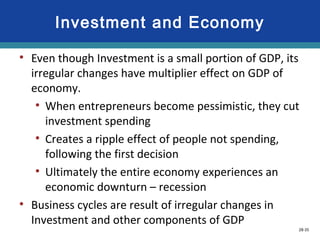

This document discusses key macroeconomic relationships including the components of GDP, consumption and income relationships, and the multiplier effect. It notes that GDP is equal to consumption + investment + government spending + net exports. Consumption makes up about 2/3 of GDP and is positively related to disposable income, while investment is irregular. A change in one component of GDP, such as an increase in investment, will lead to a multiplier effect where GDP increases by a larger amount than the initial change due to induced changes in other components like consumption. The size of the multiplier depends on the marginal propensity to consume.