PPT on Error Control Coding prepared by Dr. T.D. Shashikala, Associate Professor, E&C Dept., University B.D.T. College of Engineering, VTU, Davanagere, Karnataka, India.

Based on:

Digital Communication Systems – Simon Haykin, 2014

Error Control Coding – Shu Lin & Daniel J. Costello Jr., 2004

References include works by Blahut, Gravano, and Sklar.

Covers key concepts for students, educators, and researchers in digital communications.

![Minimum Distance Considerations in

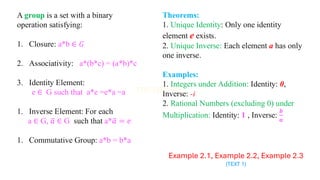

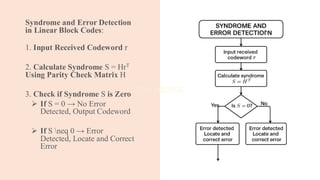

Linear Block Codes:

1. Input Codewords (Set of valid

codewords)

2. Compute Hamming Distance (Pairwise

distance between codewords)

3. Find Minimum Distance dmin

(Smallest nonzero Hamming distance)

4. Determine Error Detection &

Correction Capability

➢ t = [ (dmin - 1) / 2 ] (Error correction

capability)

➢ dmin - 1(Error detection capability)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/eccmodule12slidesharewatermark-250814141816-87992968/85/ECC-module-1-2-SLIDESHARE_watermark-pdf-83-320.jpg)

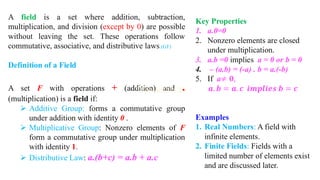

![Error Detecting and Error Correcting

Capabilities in Linear Block Codes:

1. Input Codewords and Minimum Distance dmin

2. Calculate Error Detection Capability (dmin - 1)

3. Calculate Error Correction Capability

(t = [(dmin - 1) / 2 ]

4. Determine System Capability

➢ If t is sufficient → Correct errors

➢ If not → Only detect errors](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/eccmodule12slidesharewatermark-250814141816-87992968/85/ECC-module-1-2-SLIDESHARE_watermark-pdf-84-320.jpg)

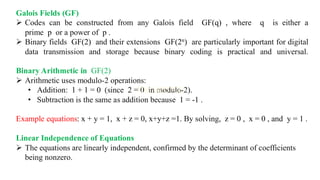

![Single Parity Check (SPC) Codes with

important equations.

1. Input Message Bits : m

2. Compute Parity Bit p Using:

p = m1 ⊕ m2 ⊕ …. ⊕ mk

(Where ⊕ is XOR operation)

3. Generate Codeword c = [m, p]

4. Transmit Codeword

5. At Receiver: Compute Syndrome S

S = c1 ⊕ c2 ⊕ …. ⊕ cn

6. Check for Errors:

➢ If S = 0, No Error.

➢ If S ≠ 0, Error Detected

(SPC can only detect single-bit errors).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/eccmodule12slidesharewatermark-250814141816-87992968/85/ECC-module-1-2-SLIDESHARE_watermark-pdf-86-320.jpg)