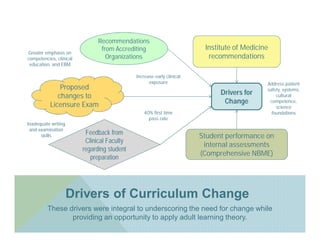

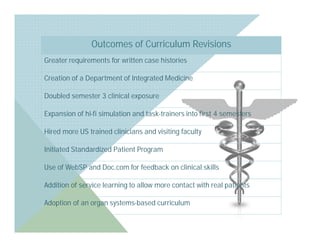

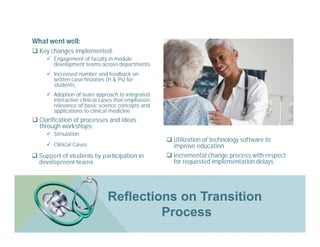

The document discusses the implementation of early clinical learning strategies at a Caribbean medical school, aiming to improve student preparedness for practice in the United States. Key changes include increased clinical exposure, engagement in module development, and the adoption of technology for feedback on clinical skills, while challenges such as faculty engagement and communication barriers are noted. Recommendations emphasize a focus on competencies and the application of adult learning theory to enhance education outcomes.