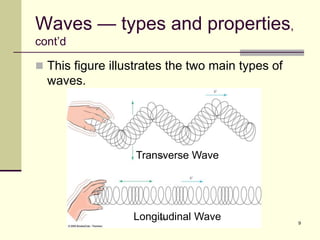

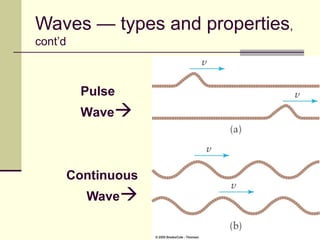

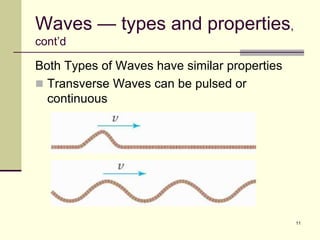

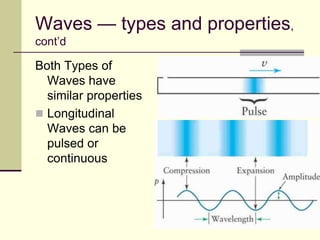

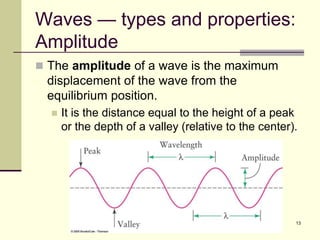

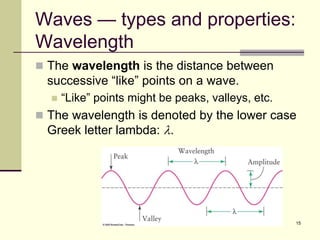

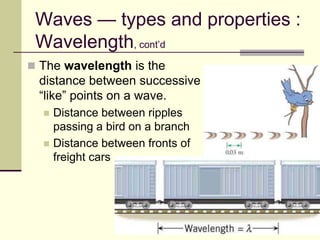

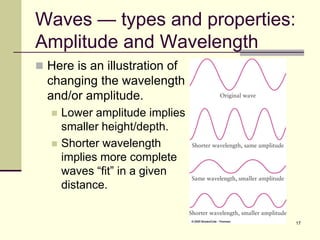

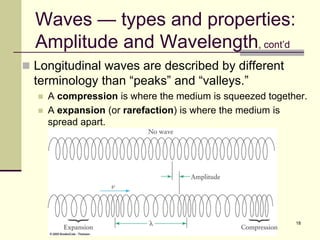

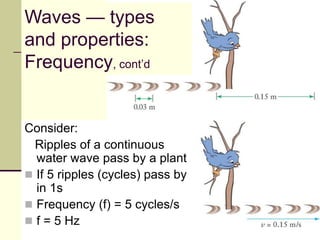

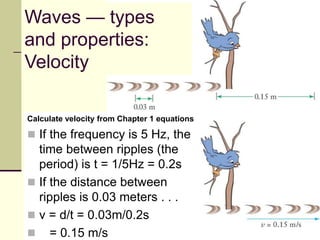

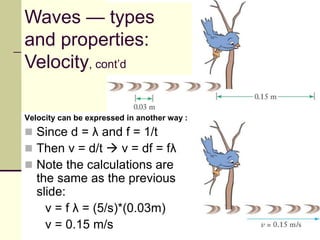

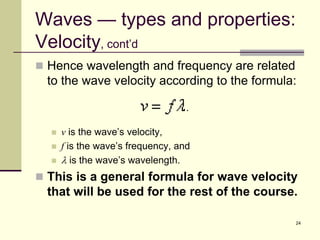

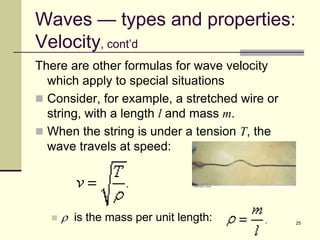

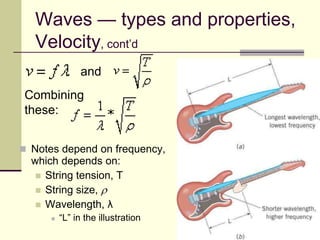

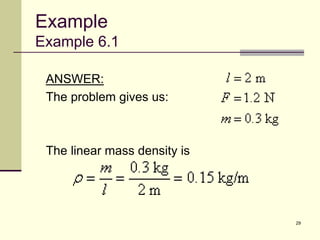

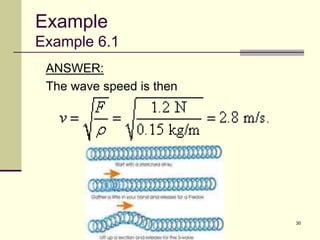

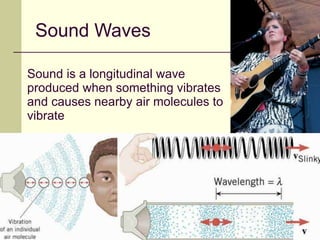

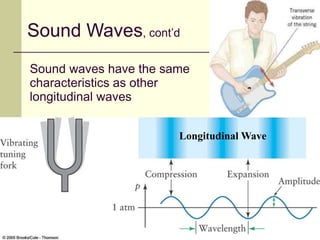

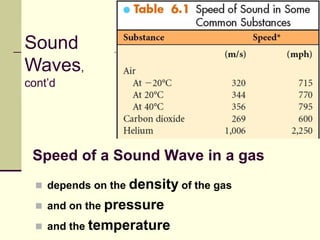

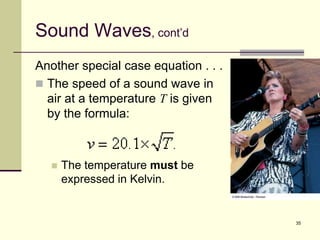

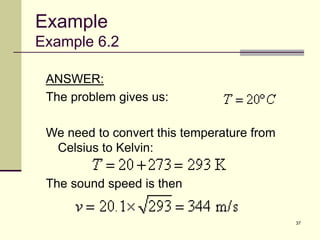

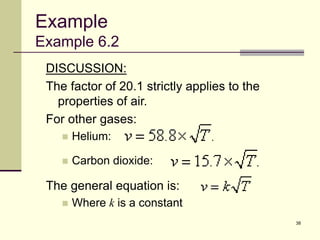

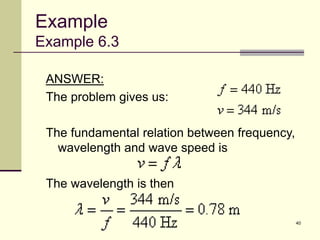

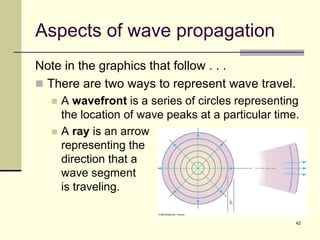

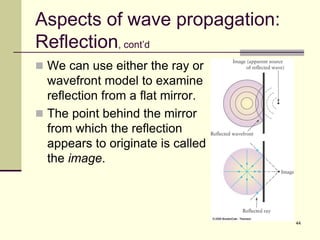

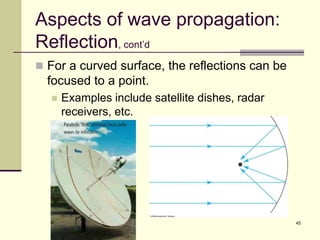

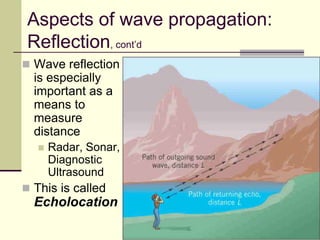

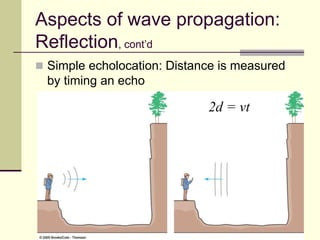

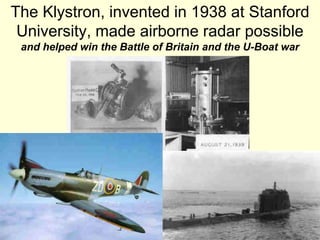

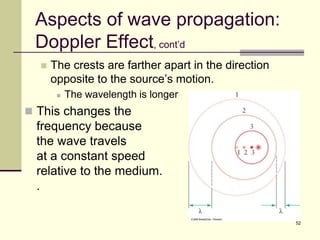

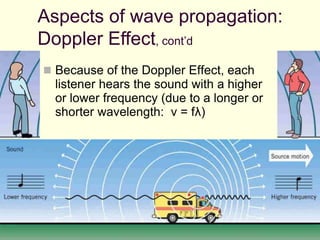

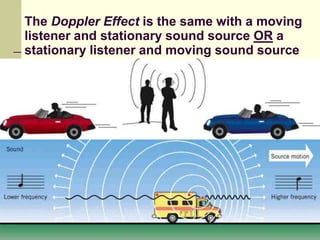

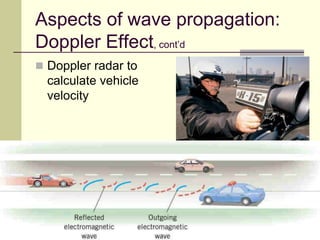

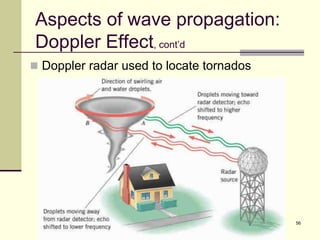

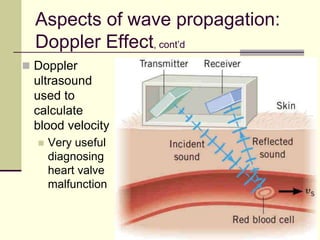

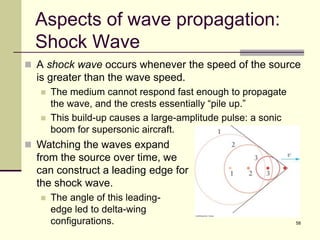

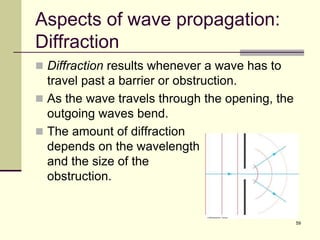

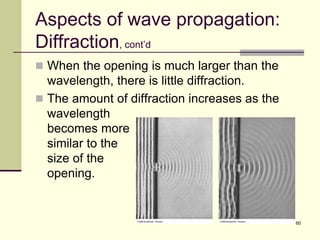

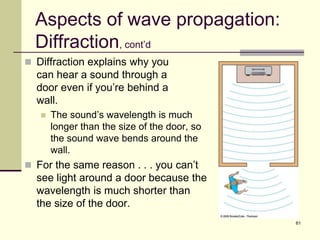

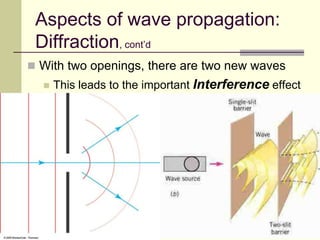

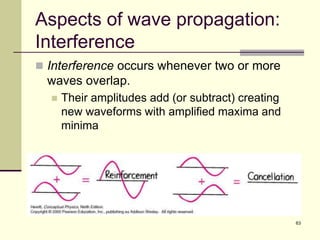

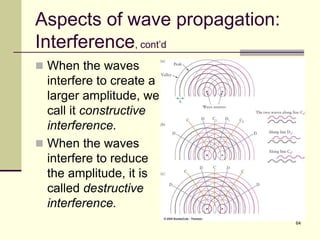

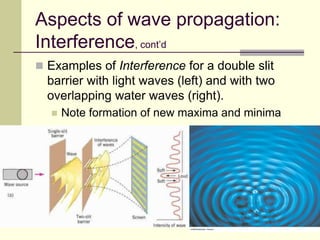

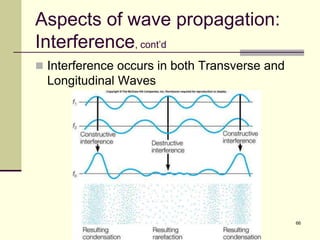

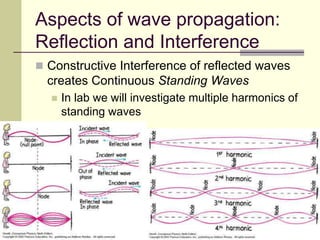

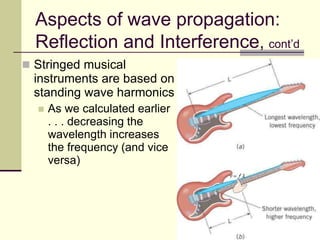

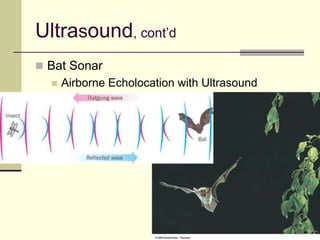

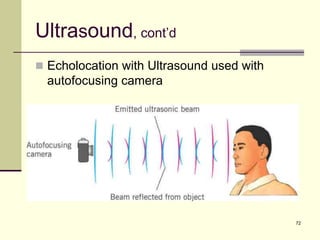

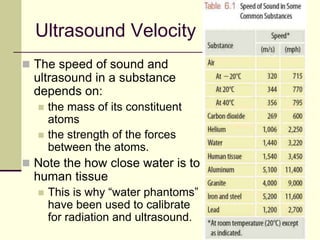

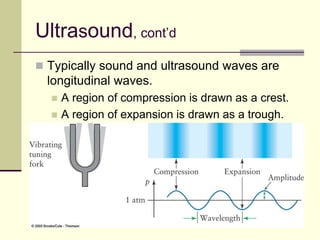

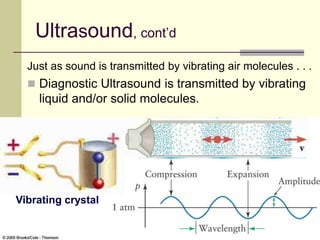

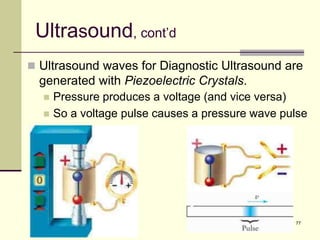

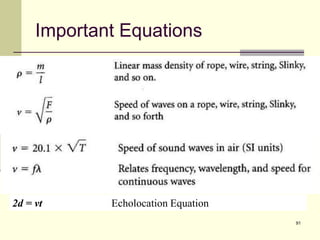

This document provides an overview of PHY 110 Introduction to Physics taught by Dr. Henry. It outlines the course content for the rest of the semester, which will cover chapters on waves, electricity, electromagnetism, atomic physics, nuclear physics, and special relativity. It then summarizes key concepts about waves, including the properties of transverse and longitudinal waves. It discusses sound as a longitudinal wave and provides the formula for the speed of sound. The document concludes by covering various aspects of wave propagation such as reflection, the Doppler effect, shock waves, diffraction, and interference.