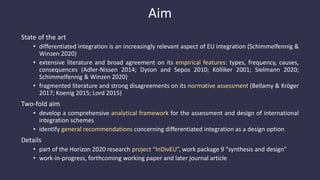

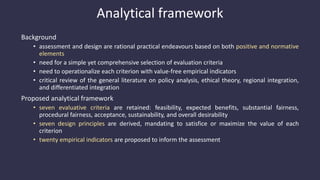

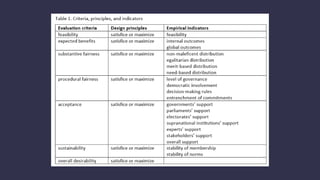

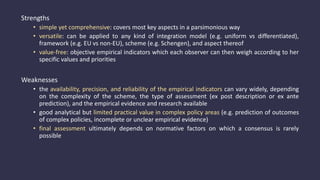

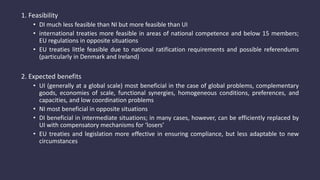

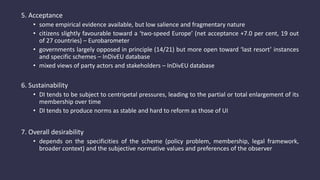

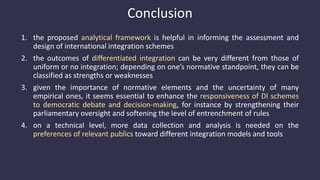

The document outlines an analytical framework for assessing differentiated integration schemes in the EU. It evaluates such schemes based on 7 criteria: feasibility, expected benefits, fairness, acceptance, sustainability, and desirability. Differentiated integration is defined as selective application of rules to some but not all EU members. It is relatively common in the EU but still less so than national or EU-wide legislation. The outcomes of differentiated integration can vary significantly depending on the scheme but it may increase inequality and distance between insiders and outsiders. More empirical analysis is needed to better understand public preferences regarding integration models.