The document discusses dementia, including its various types and classifications. It provides details on Alzheimer's disease, including its pathogenesis, clinical features, diagnosis, and prevalence. Alzheimer's disease is the most common cause of dementia, usually having an insidious onset and progressive cognitive decline characterized by amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the brain.

![NMDA [glutamate] antagonist

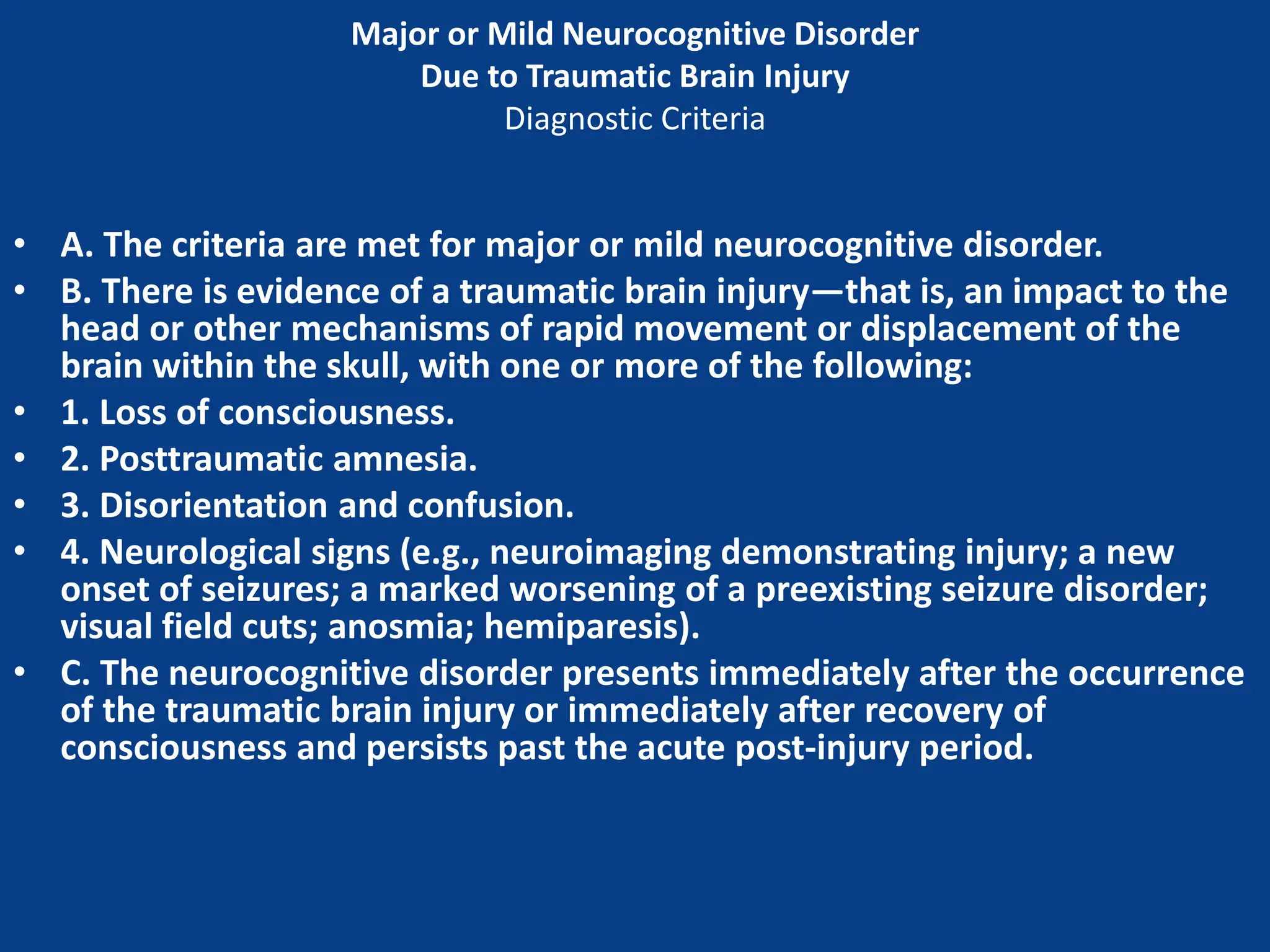

Memantine

◦ Precautions: Dizziness, headache, alkalinized

urine (ATN, UTI) seizures, GI upset

◦ Interactions: Other NMDA antagonists

(amantadine, dextromethorphan), decreased

by renally-excreted drugs](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dementiabydrajaz-231206134431-877ea082/75/dementia-by-dr-ajaz-pptx-137-2048.jpg)