This document provides information about the fifth edition of the textbook "Engineering Drawing & Design" by David A. Madsen and David P. Madsen. It lists the authors and their qualifications and experience in engineering drafting. It also provides basic copyright information and notices about the electronic version of the textbook. The document gives an overview of the authors and scope of the textbook without providing many details about its content.

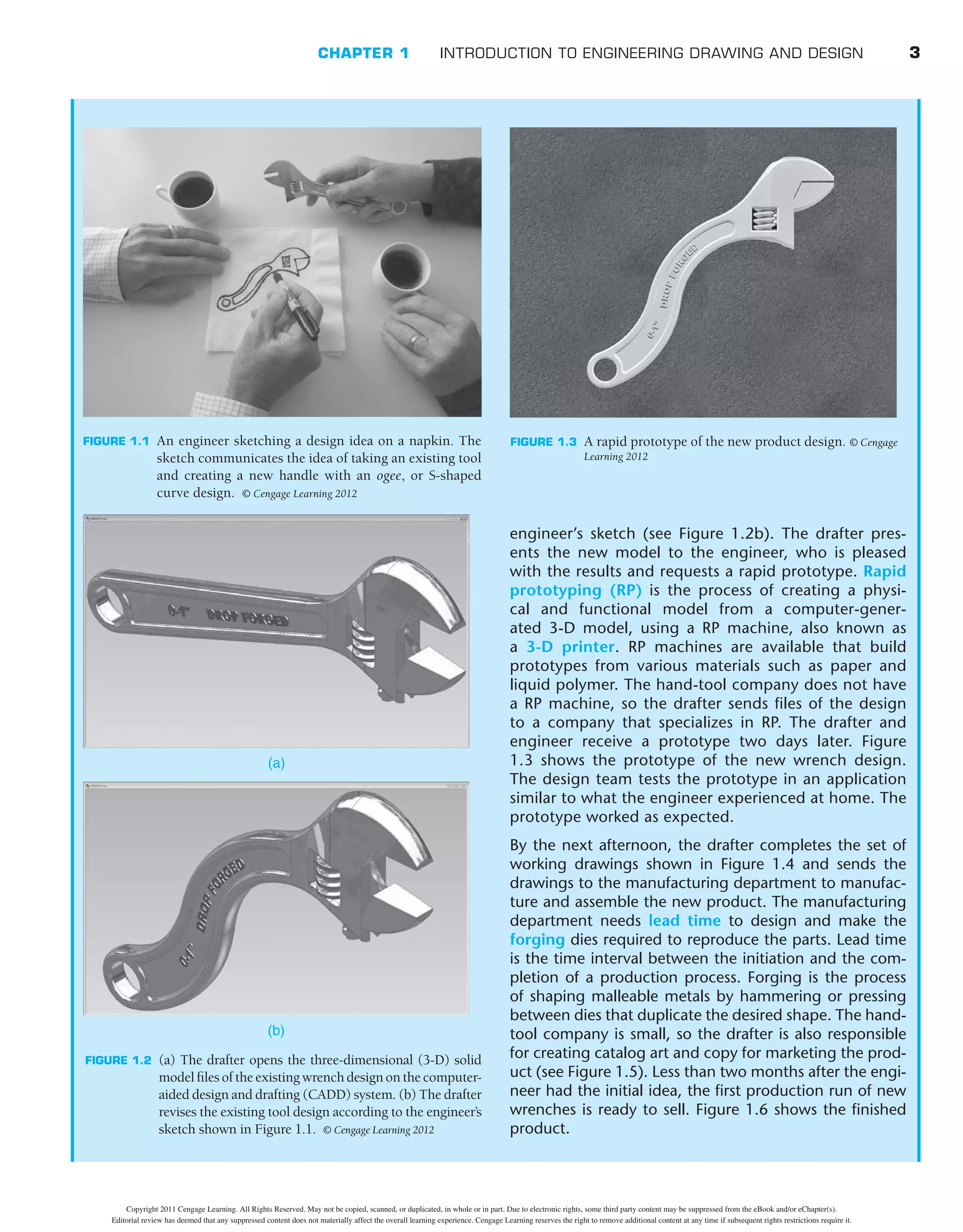

![22 SECTION 1 Introduction to Engineering Drawing and Design

and photographs by methods and techniques suited to speci-

fied reproduction process or final use, photo-offset, and pro-

jection transparencies, using drafting and optical equipment.

Technical illustrators create schematic, perspective, axono-

metric, orthographic, and oblique-angle views to depict func-

tions, relationships, and assembly sequences of parts and

assemblies such as gears, engines, and instruments. Techni-

cal illustrators also create rendered drawings and 3-D mod-

els, and they may draw cartoons and caricatures to illustrate

operation, maintenance, and safety manuals and posters (see

Figure 1.28).

Tool-and-Die Design Drafter

Tool-and-die design drafting is a specialization of mechanical

drafting. Tool-and-die design drafters prepare CADD models

and detailed drawing plans for manufacturing tools, usually fol-

lowing designs and specifications indicated by tool designers.

.300

1.740

2.300

4X .75

2X .250-20 UNC-2B

SHOWN

PROJECT:

DRAWN

CHECK

DESIGN

ENGR

APPR

DATE

TITLE

SIZE CAGE DWG. NO.

SCALE PRINTED:

REVISIONS

DESCRIPTION

ZONE LTR DATE APPROVED

REV

DWG NO.

Portland Or 97224

16505 SW 72nd Ave

FLIR Systems Inc.

CALC. WT.

FINISH

MATERIAL

DECIMALS .XX

.XXX

HOLE Ø .XX

.XXX

ANGLES 0°30'

BENDS ±2°

FRACTIONS ± 1/32 STRAIGHTNESS &/OR

FLATNESS: .005/IN

THREADS:

EXTERNAL-CLASS 2A

INTERNAL-CLASS 2B

ANGLES,BENDS,&

INTERSECTIONS:90°

MACHINED SURFACES:

SAMPLES MUST BE APPROVED BY ENG.

PRIOR TO STARTING PRODUCTION

63 OR BETTER

7

A

8 6 5 4 3 2 1

B

C

D

A

B

C

D

8 7 6 5 4 3 1

REV

SHEET OF

D 64869

+

-

UNLESS OTHERWISE SPECIFIED

DIMENSIONS ARE IN INCHES ALL

DIMENSIONS IN [ ] ARE MM DO NOT

SCALE DRAWING

PERPEND. .003/IN

CONCEN. .003/IN

03-001864 0

SADDLE - TELESCOPE

LENS MTG

AL, 6061-T6

CHEM FILM PER

PER QQ-A-250/11

±.005

.003

.001

±.015

±.005

MIL-C-5541, CL 3

1

1

1/1

0

4X 30°

6.20

R2.100

35°

2X 113°

1.700

.120

.400

2X R1.950

R1.852 ±.001

VIEW A-A

3.10

2X 1.23

(3.58)

R1.805

15°

30°

2X 67°

1.70

.500

6X .138-32 UNC-2B

.25 MIN

A

2X .250-20 UNC-2B

.30 MIN

.10

R.25

2.100 .95

.50

2.100

30°

2X 67°

2X .40

2.350

.030

.060

5.400

.44 MIN

2X 113°

2.700

R2.350

2X .125

2.350

4X Ø.270 ±.010 THRU

Ø.44 .43

4

.420

2.000

2X 60°

4X R3.000

.60

2X 1.250

1.70

1.25

.12 X 45°

4

5X .280

SHOWN

SHOWN

Ø.28

Ø.44

5X Ø.180 THRU

Ø.312 .25

NOTES:

1. INTERPRET DRAWING IAW MIL-STD-100.

2. DIMENSIONS AND TOLERANCES PER ASME Y14.5-2009.

3. PART TO BE FREE OF BURRS AND SHARP EDGES.

4. IDENTIFY IAW MIL-STD-130, BY RUBBER STAMP OR HAND MARK, CONTRASTING

COLOR, .12 HIGH GOTHIC STYLE CHARACTERS, INCLUDE LATEST REV LEVEL:

64869-XXXXXXXX REV_. LOCATE APPROX AS SHOWN.

A

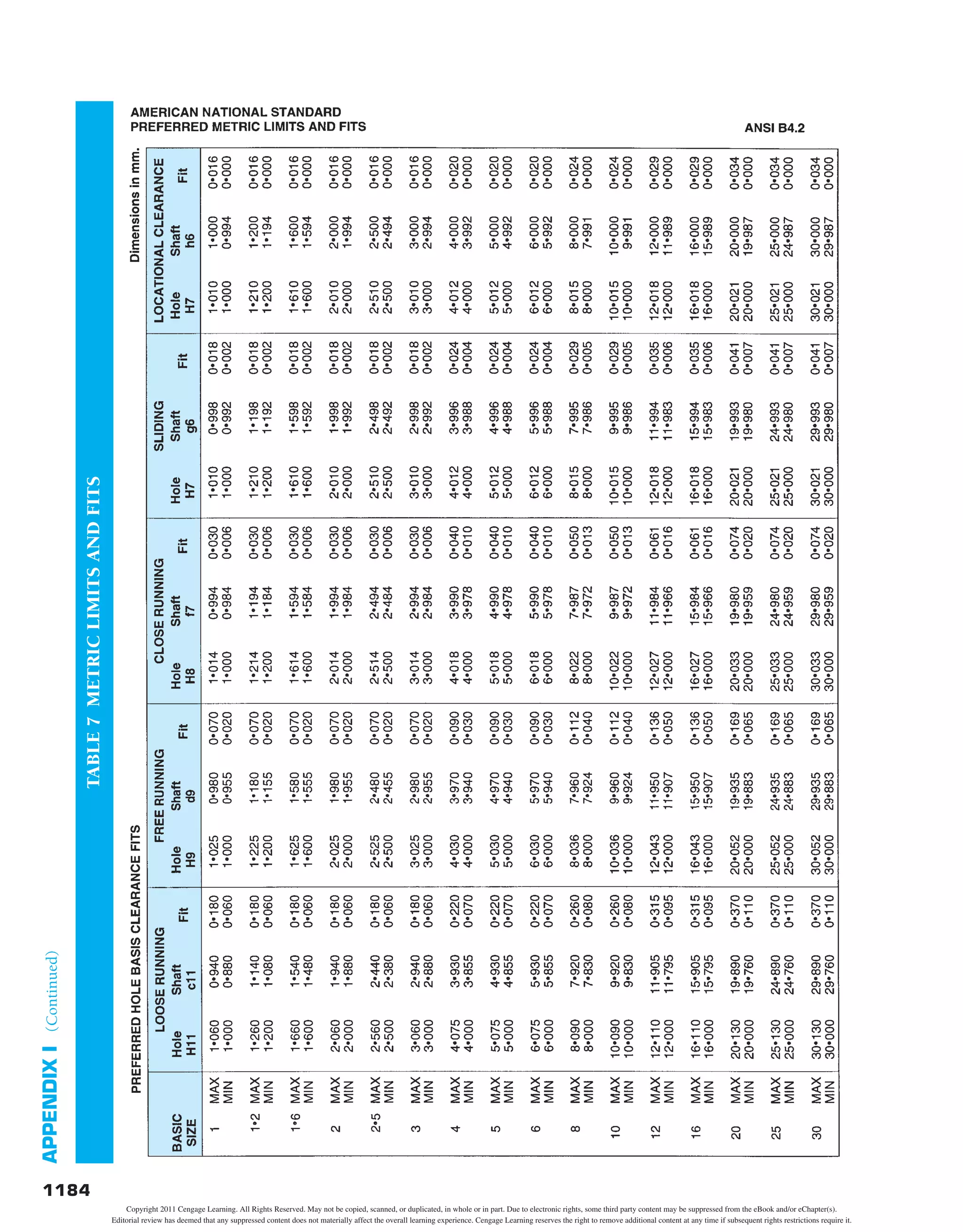

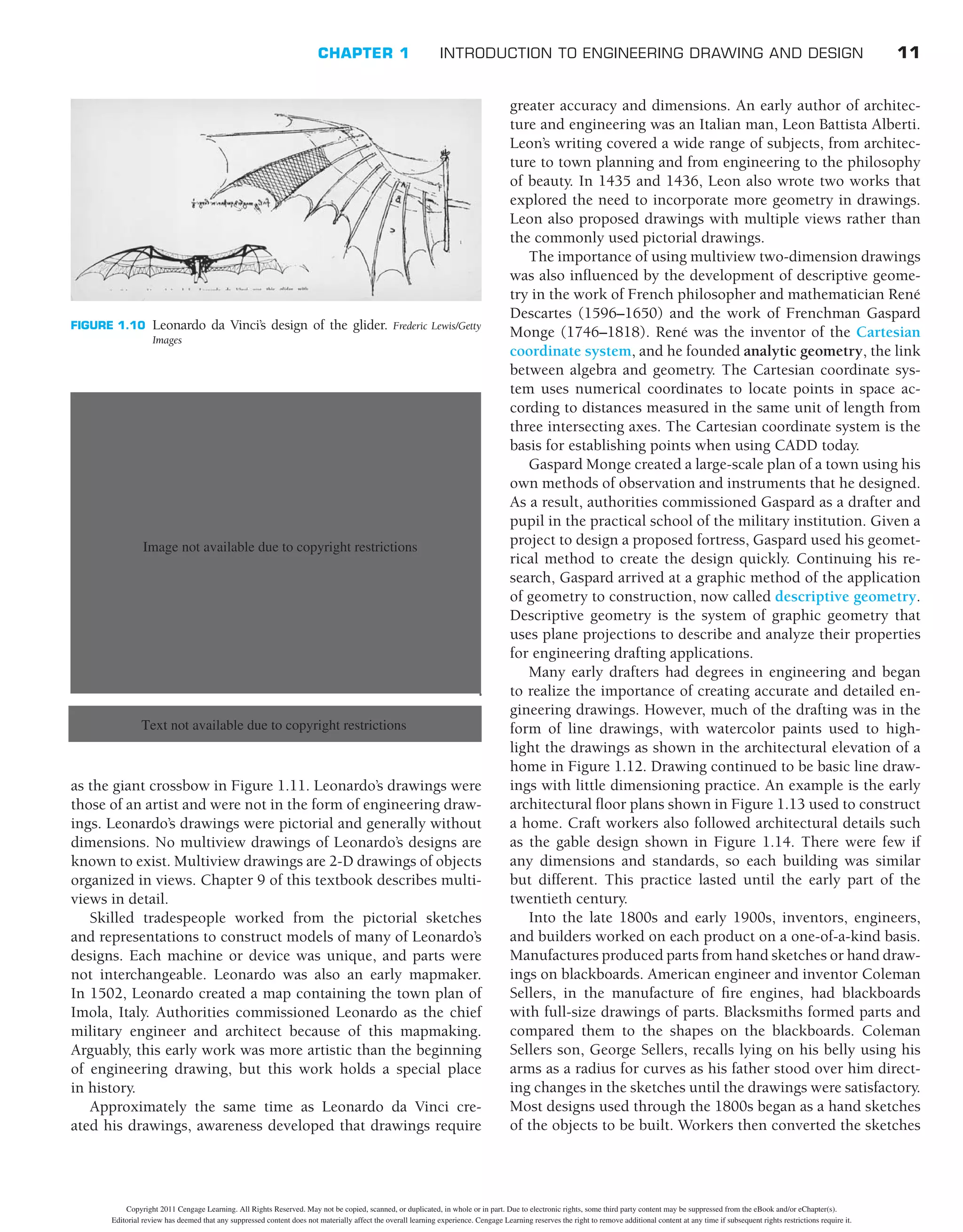

FIGURE 1.25 A mechanical drawing of a part for a thermal camera assembly. Courtesy FLIR Systems, Inc.

EDUCATION AND QUALIFICATIONS

The design and drafting profession can provide a rewarding

career for people who enjoy detailed work and have a mechan-

ical aptitude and ability to visualize. Math and communication

skills are also important. The following information describes

education and qualification requirements for an entry-level

drafting position. The information is taken partly from the

Occupational Outlook Handbook published by the U.S. Depart-

ment of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics (www.bls.gov/oco).

High school courses in mathematics, science, computer tech-

nology, design, computer graphics, and drafting are useful for

people considering a drafting career. However, employers in

the drafting industry prefer applicants who have at least two

years of postsecondary training in a drafting program that pro-

vides strong technical skills and considerable experience with

CADD systems. Employers are most interested in applicants

with a strong background in fundamental drafting principles;

Copyright 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/davidp-230925180757-12bdde0f/75/David-P-Madsen-David-A-Madsen-Engineering-Drawing-and-design-pdf-52-2048.jpg)

![122 SECTION 1 Introduction to Engineering Drawing and Design

that retains its strength under high temperatures. Because of their

great heat resistance, refractories are used for high-temperature

applications such as furnace liners. Composites are two or more

materials that are bonded together by adhesion, a force that

holds together the molecules of unlike substances when the sur-

faces come in contact. These materials generally require carbide

cutting tools or special methods for machining.

Ferrous Metals

The two main types of ferrous metals are cast iron and steel.

These metals contain iron. There are many classes of cast iron

and steel that are created for specific types of application based

on their composition.

Cast Iron

There are several classes of cast iron, including gray, white,

chilled, alloy, malleable, and nodular. Cast iron is primarily an

alloy of iron and 1.7% to 4.5% of carbon, with varying amounts

of silicon, manganese, phosphorus, and sulfur.

G r a y C a s t I r o n

Gray iron is a popular casting material for automotive cylinder

blocks, machine tools, agricultural implements, and cast iron

pipe. Gray cast iron is easily cast and machined. It contains

1.7% to 4.5% carbon and 1% to 3% silicon.

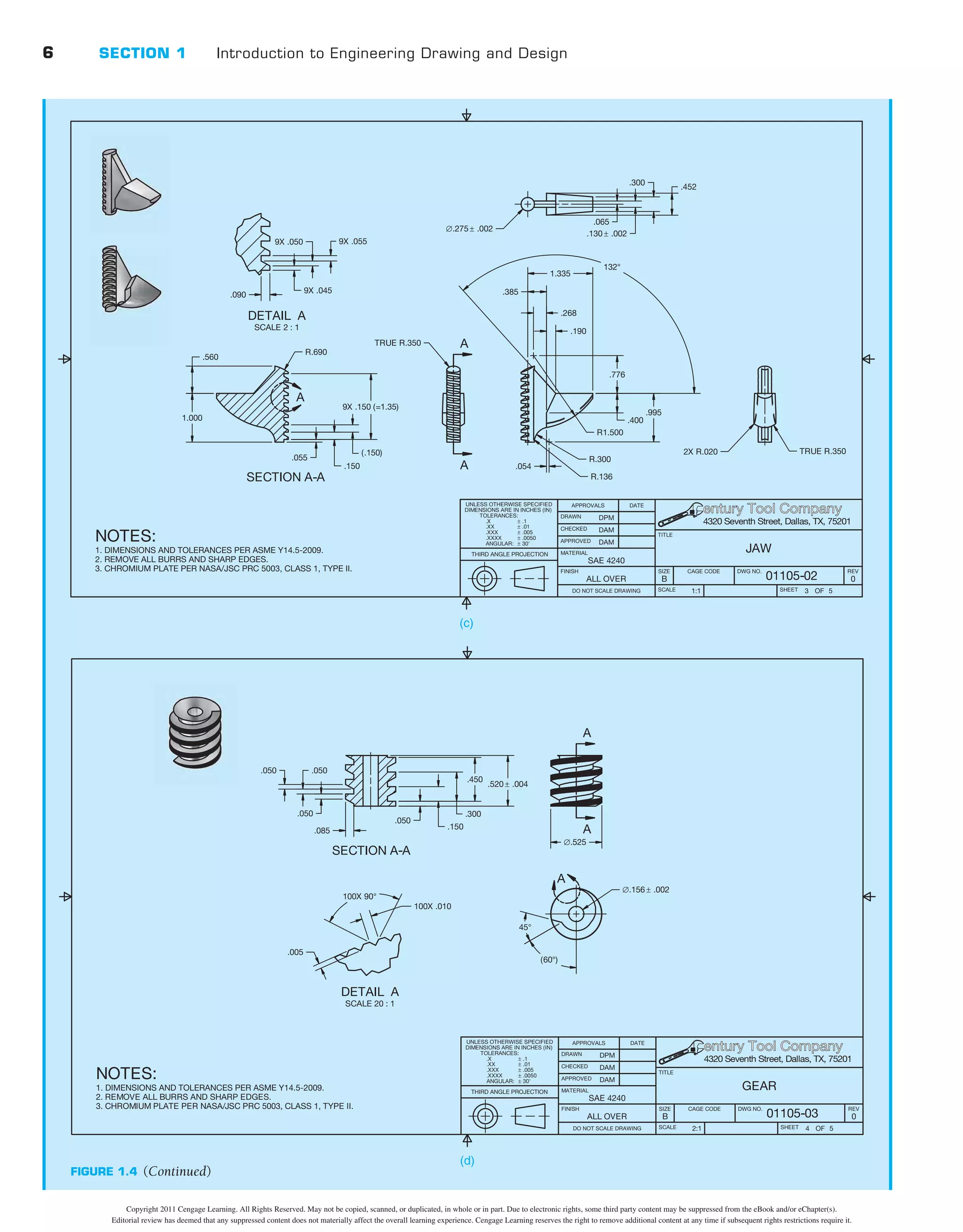

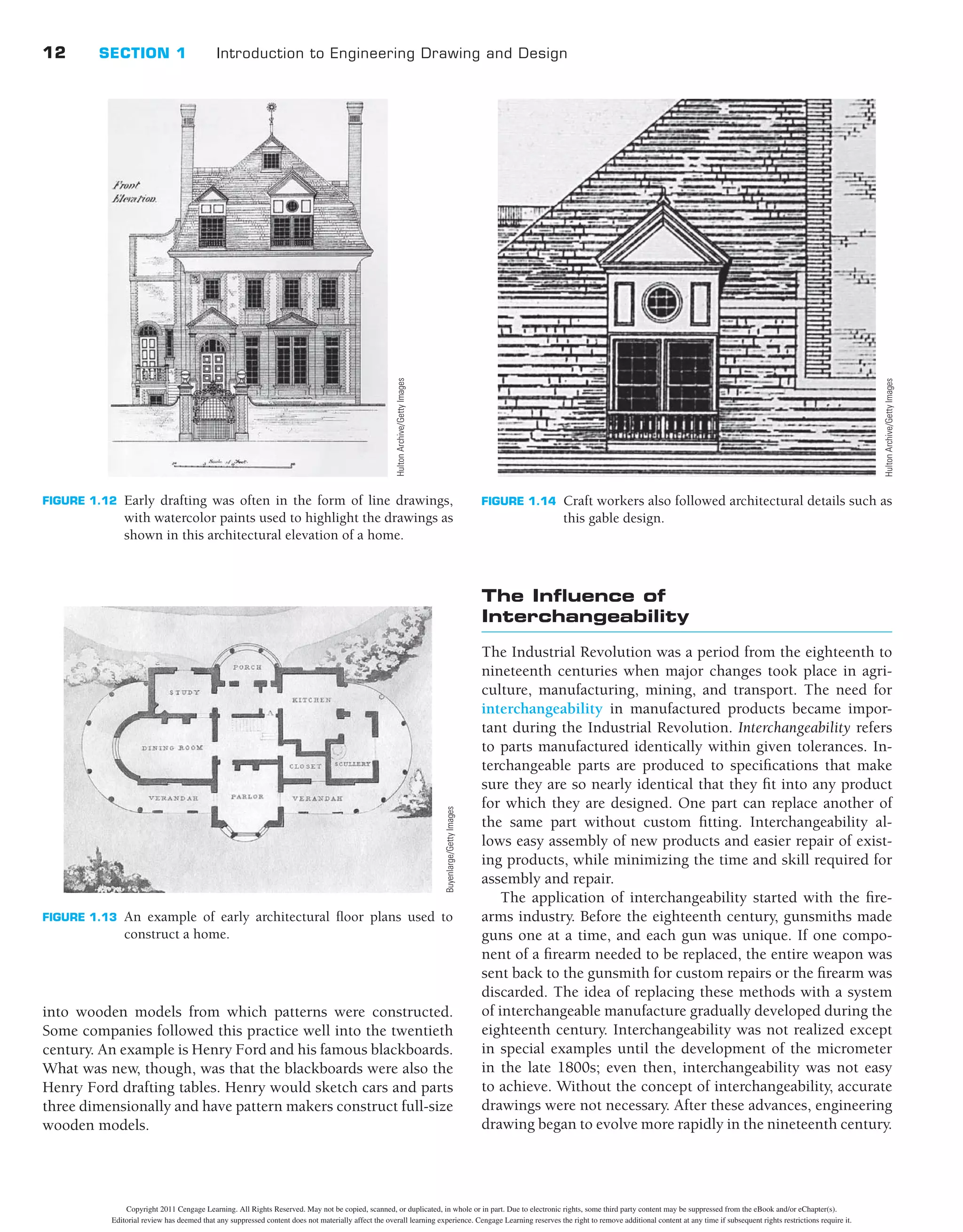

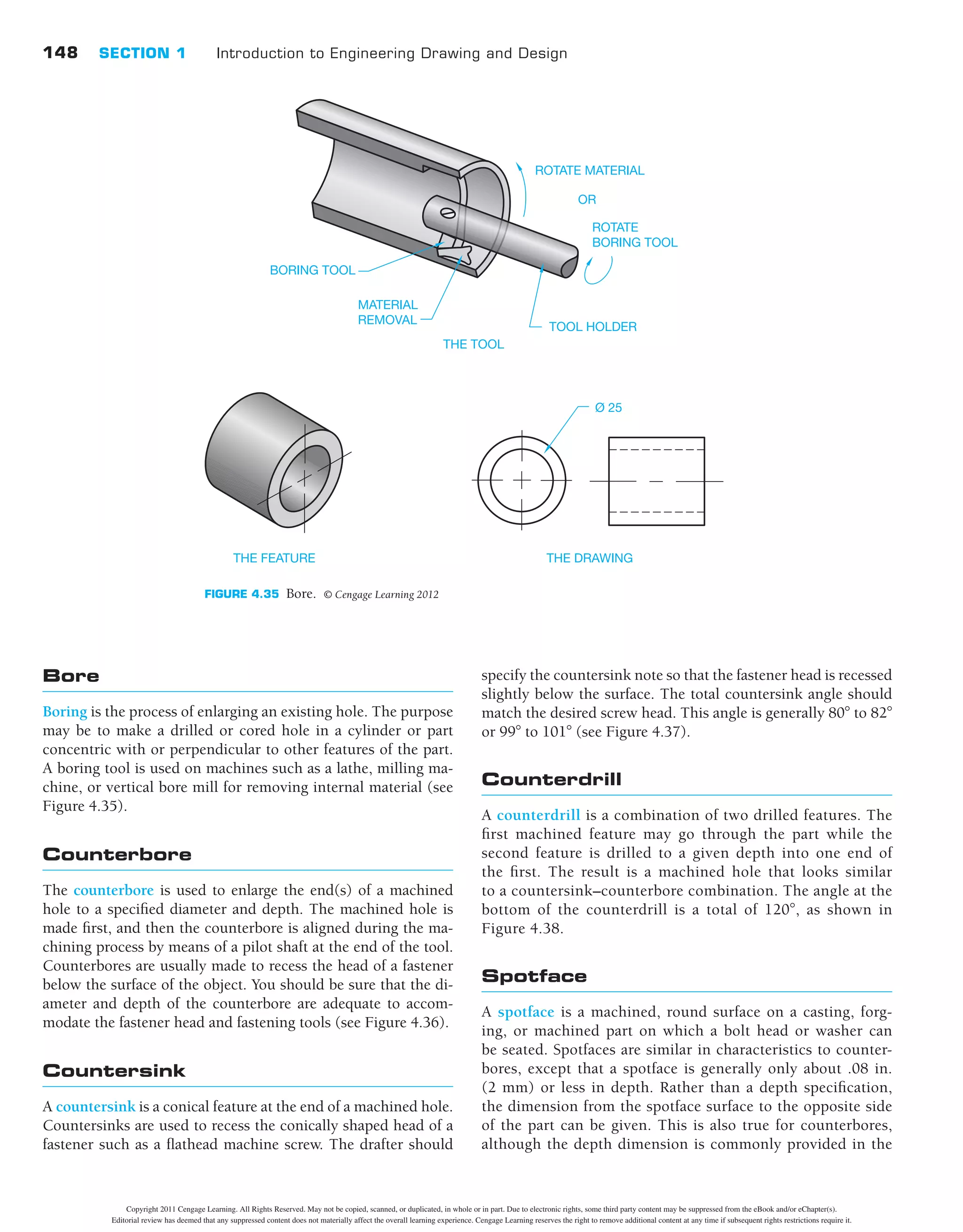

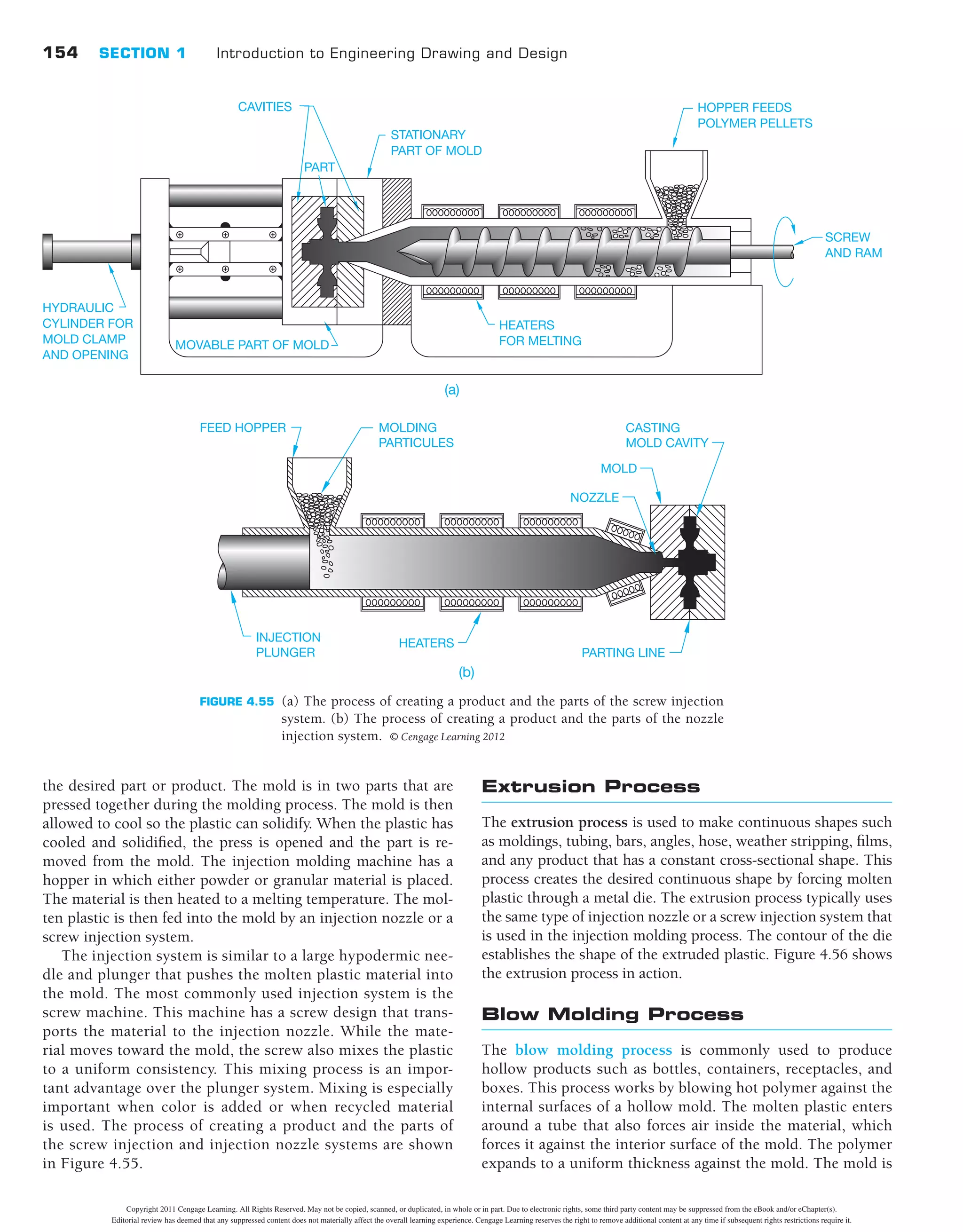

INTRODUCTION

A number of factors influence product manufacturing. Begin-

ning with research and development (R&D), a product should

be designed to meet a market demand, have good quality, and

be economically produced. R&D is the first phase used to deter-

mine the feasibility of new products or the evolution of existing

products using creativity, market research, product research,

and prototype development. The sequence of product develop-

ment begins with an idea and results in a marketable commod-

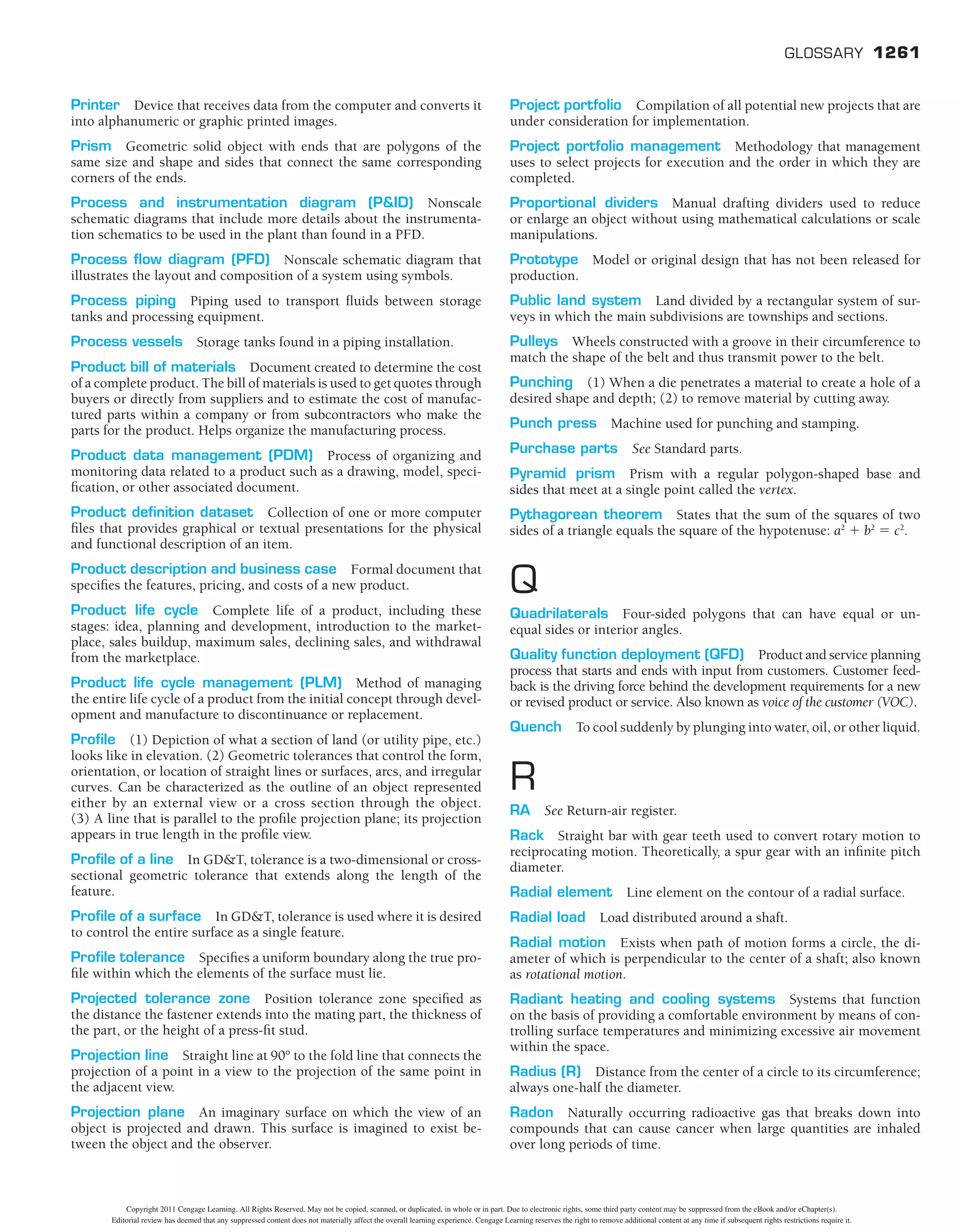

ity as shown in Figure 4.2.

MANUFACTURING MATERIALS

A wide variety of materials available for product manufacturing

fall into three general categories: metal, plastic, and inorganic

materials. Metals are classified as ferrous, nonferrous, and alloys.

Ferrous metals contain iron in some form such as cast iron and

steel. Nonferrous metals do not have iron content; for example,

copper and aluminum. Alloys are mixtures of two or more metals.

Plastics or polymers have two types of structure: thermoplastic

and thermoset. Thermoplastic material can be heated and formed

by pressure and the shape can be changed on reheating. Thermoset

plastics are formed into a permanent shape by heat and pressure

and cannot be altered by heating after curing. Plastics are molded

into shape and only require machining for tight tolerance situa-

tions or when holes or other features are required, features that

would be impractical to produce in a mold. It is common practice

to machine some plastics for parts, such as gears and pinions.

Inorganic materials include carbon, ceramics, and compos-

ites. Carbon and graphite are classified together and have prop-

erties that allow molding by pressure. These materials have low

tensile strength (the ability to be stretched) and high compres-

sive strength, with increasing strength at increased tempera-

tures. Ceramics are clay, glass, refractory, and inorganic cements.

Ceramics are very hard, brittle materials that are resistant to heat,

chemicals, and corrosion. Clay and glass materials have an amor-

phous structure, whereas refractories must be bonded together

by applying temperatures. A refractory is a nonmetallic material

RESEARCH

AND

DEVELOPMENT

PROTOTYPE

DRAWINGS

DISTRIBUTION

AND

SALES

PROTOTYPE

CONSTRUCTION

OR

MODELING

ASSEMBLY

ENGINEERING

DRAWINGS

AND

DOCUMENTS

MANUFACTURING

PROCESSES

FIGURE 4.2 Sequence of product development. © Cengage Learning 2012

ASTM The American Society for Testing Materials

(ASTM) specifications A48–76 group gray cast iron into

two classes: (1) easy to manufacture (20A, 20B, 20C,

25A, 25B, 25C, 30A, 30B, 30C, 35A, 35B, 35C) and (2)

more difficult to manufacture (40B, 40C, 45B, 45C, 50B,

50C, 60B, 60C). The prefix number denotes the mini-

mum tensile strength in thousand of pounds per square

inch. For more information or to order standards, go to

the ASTM Web site at www.astm.org.

STANDARDS

W h i t e C a s t I r o n

White cast iron is extremely hard and brittle, and it has almost no

ductility. Ductility is the ability to be stretched, drawn, or ham-

mered thin without breaking. Caution should be exercised when

using this material because thin sections and sharp corners may

be weak, and the material is less resistant to impact uses. This cast

ironissuitedforproductswithmorecompressivestrengthrequire-

ments than gray cast iron [compare more than 200,000 pounds

per square inch (psi) with 65,000 to 160,000 psi]. White cast iron

is used where high wear resistance is required.

C h i l l e d C a s t I r o n

An outer surface of white cast iron results when gray iron cast-

ings are chilled rapidly. This chilled cast iron material has the

internal characteristics of gray cast iron and the surface advan-

tage of white cast iron.

Copyright 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/davidp-230925180757-12bdde0f/75/David-P-Madsen-David-A-Madsen-Engineering-Drawing-and-design-pdf-152-2048.jpg)

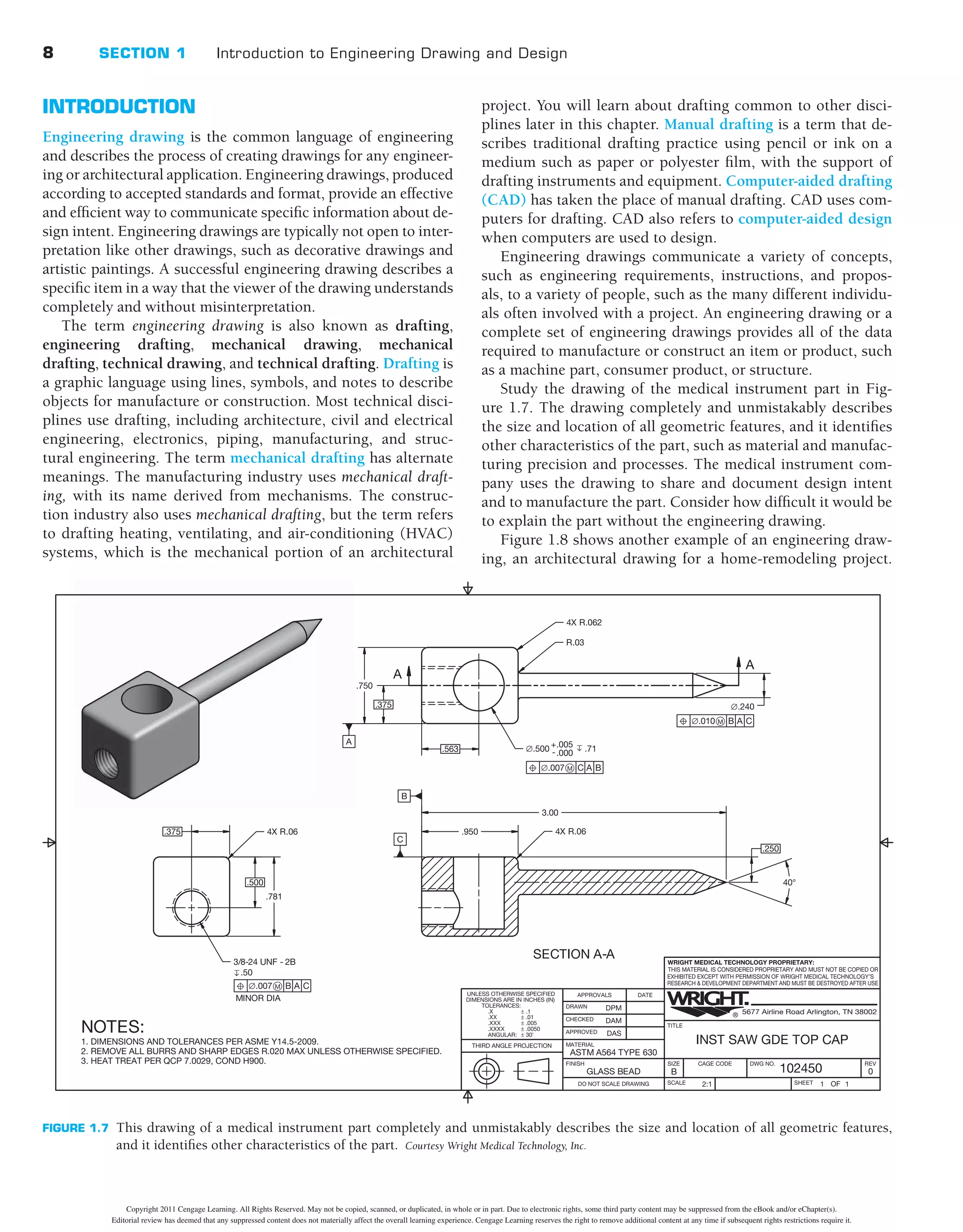

![OBJECT

LINES

SECTION

LINES

DIMENSION

LINES

EXTENSION

LINES

HIDDEN

LINES

LEADER

CENTERLINES

PHANTOM

LINE

CUTTING-PLANE

LINE

PROJECT:

DRAWN

CHECK

DESIGN

ENGR

APPR

DATE

TITLE

SIZE

CAGE

DWG.

NO.

SCALE

PRINTED:

REVISIONS

DESCRIPTION

ZONE

LTR

DATE

APPROVED

REV

DWG

NO.

Portland

Or

97224

16505

SW

72nd

Ave

FLIR

Systems

Inc.

CALC.

WT.

FINISH

MATERIAL

DIMENSIONS

ARE

IN

INCHES

UNLESS

OTHERWISE

SPECIFIED

DECIMALS

.XX

.XXX

HOLE

ÿ

.XX

.XXX

ANGLES

0º30'

BENDS

±

2º

PERPEND.

.003/IN

CONCEN

.003/IN

FRACTIONS

±

1/32

STRAIGHTNESS

&/OR

FLATNESS:

.005/IN

THREADS:

EXTERNAL-CLASS

2A

INTERNAL-CLASS

2B

ANGLES,BENDS,

&

INTERSECTIONS:

90º

MACHINED

SURFACES:

SAMPLES

MUST

BE

APPROVED

BY

ENG.

PRIOR

TO

STARTING

PRODUCTION

DO

NOT

SCALE

DRAWING

63

OR

BETTER

ALL

DIMENSIONS

IN

[

]

ARE

MM

7

A

8

6

5

4

3

2

1

B

C

D

A

B

C

D

8

7

6

5

4

3

1

REV

SHEET

OF

D

64869

+

-

SADDLE

-

TELESCOPE

LENS

MTG

AL,

6061-T6

CHEM

FILM

PER

PER

QQ-A-250/11

±

.005

.003

.001

±

.015

±

.005

MIL-C-5541,

CL

3

1

1

1/1

.300

1.740

2.300

4X

.75

2X

.250-20

UNC-2B

SHOWN

4X

30º

6.20

R2.100

35º

2X

113º

1.700

.120

.400

2X

R1.950

R1.852

±

.001

VIEW

A-A

3.10

2X

1.23

(3.58)

R1.805

15º

30º

2X

67º

NOTES:

CONTRASTING

COLOR,

.12

HIGH

GOTHIC

STYLE

CHARACTERS,

INCLUDE

IDENTIFY

IAW

MIL-STD-130,

BY

RUBBER

STAMP

OR

HAND

MARK,

PART

TO

BE

FREE

OF

BURRS

AND

SHARP

EDGES.

INTERPRET

DIMENSIONS

AND

TOLERANCES

PER

ANSI

Y14.5-2009.

LATEST

REV

LEVEL:

64869-XXXXXXXX

REV_.

LOCATE

APPROX

AS

SHOWN.

INTERPRET

DRAWING

IAW

MIL-STD-100.

3.

4

2.

1.

1.70

.500

.25

MIN

A

2X

.250-20

UNC-2B

.30

MIN

.10

R.25

2.100

.95

.50

2.100

30º

2X

67º

2X

.40

2.350

.030

.060

5.400

.44

MIN

2X

113º

2.700

R2.350

2X

.125

2.350

4X

Ø.270

±

.010

THRU

Ø.44

.43

5

.420

2.000

2X

60º

4X

R3.000

.60

2X

1.250

1.70

1.25

A

.12

X

45º

5

5X

.280

SHOWN

SHOWN

Ø.28

Ø.44

5X

Ø.180

THRU

Ø.312

.25

6X

.138-32

UNC-2B

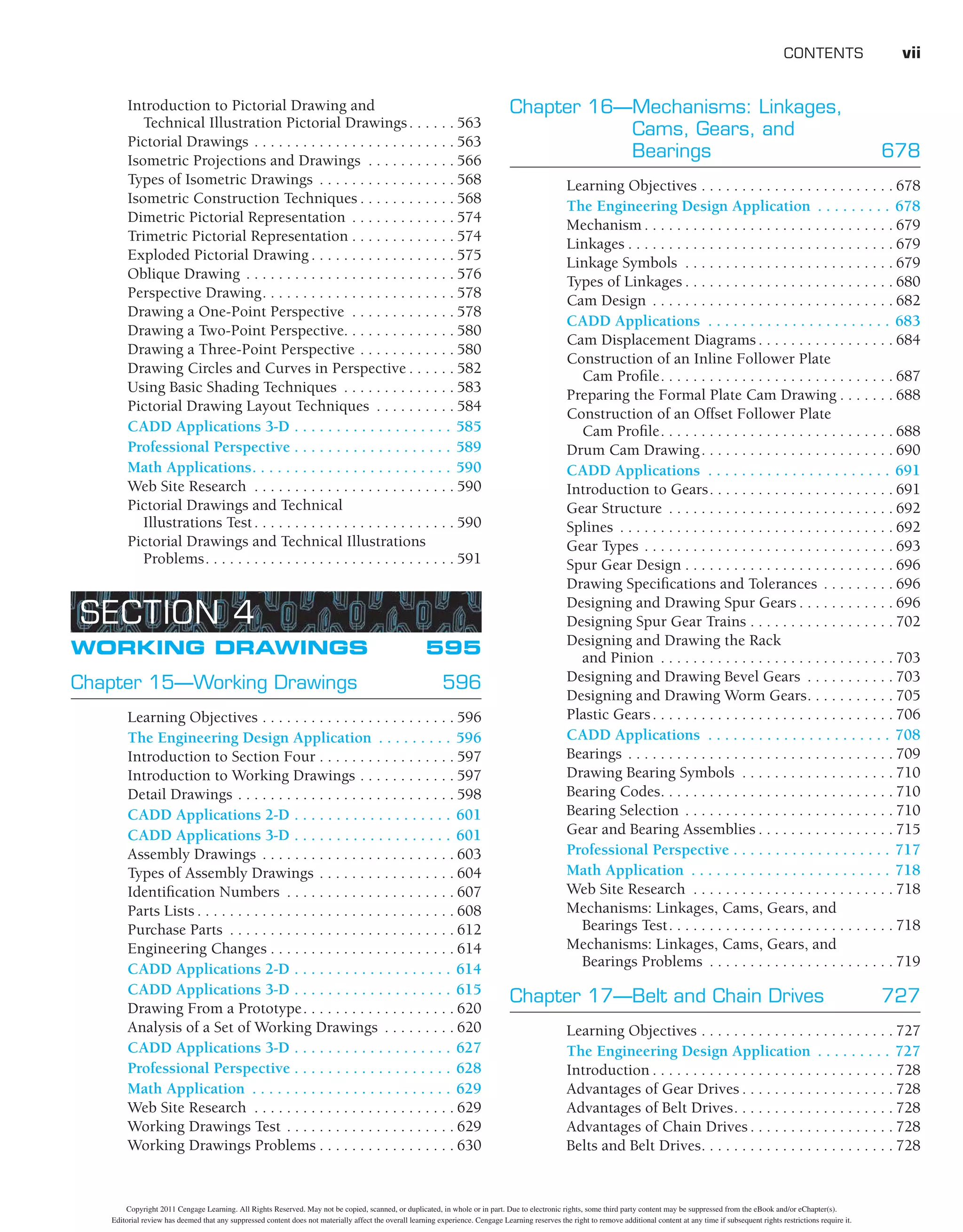

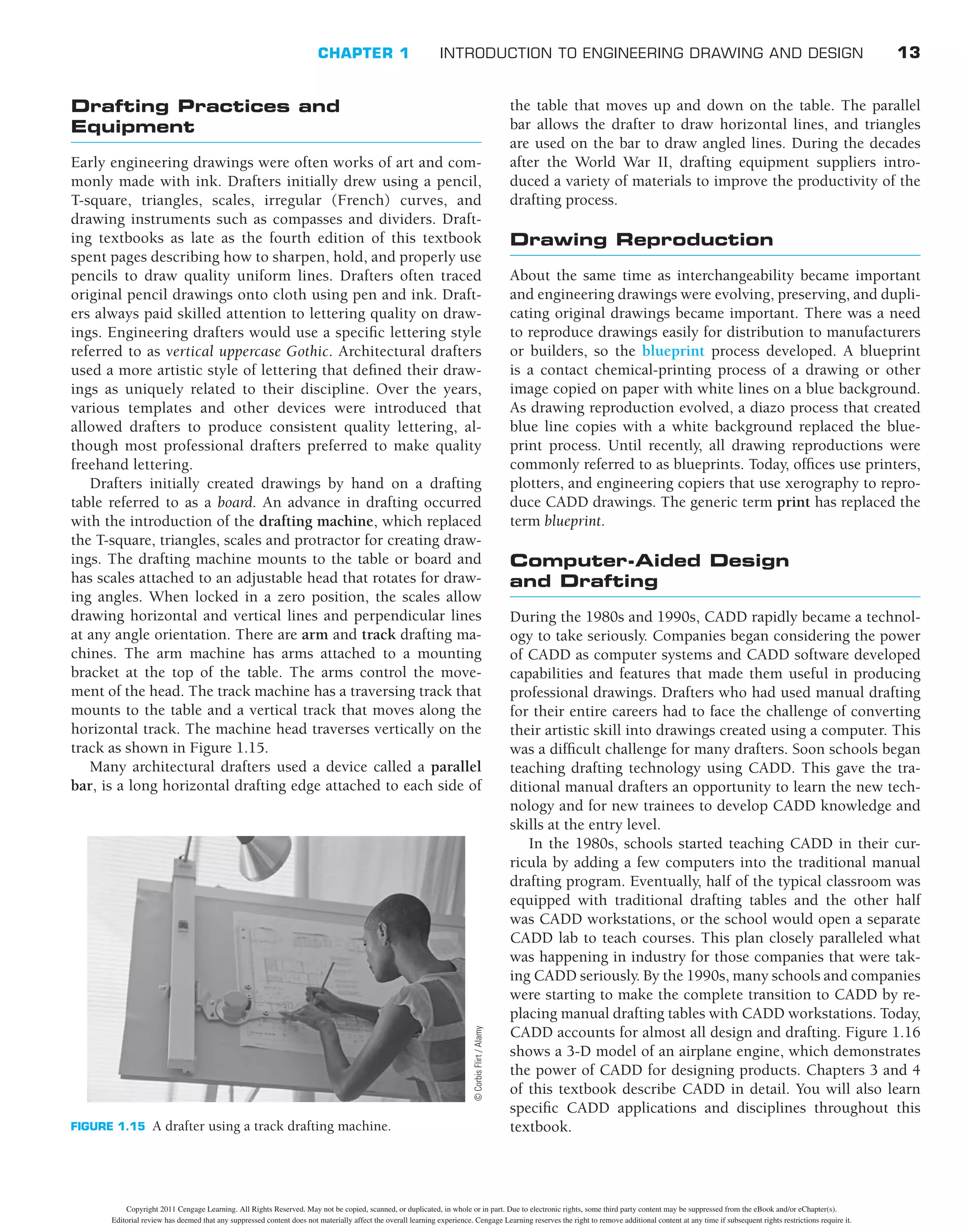

FIGURE

6.45

A

real-world

drawing

with

a

variety

of

line

types

identifi

ed.

Courtesy

FLIR

Systems,

Inc.

213

Copyright 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/davidp-230925180757-12bdde0f/75/David-P-Madsen-David-A-Madsen-Engineering-Drawing-and-design-pdf-243-2048.jpg)