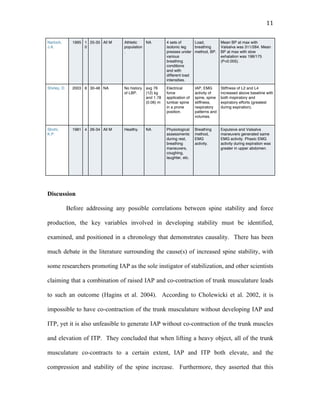

This document is a literature review investigating the relationship between intra-abdominal pressure, spine stability, and force production during weightlifting. The review examines 28 studies on how breathing patterns and increased intra-abdominal pressure through breath holding can improve spine stability and potentially increase force production. Many studies found correlations between increased intra-abdominal pressure, greater muscle activation of trunk muscles, and improved spine stability. However, the relationship between intra-abdominal pressure, spine stability and actual force production requires more research due to flaws in previous study designs. More research is needed to draw stronger conclusions.