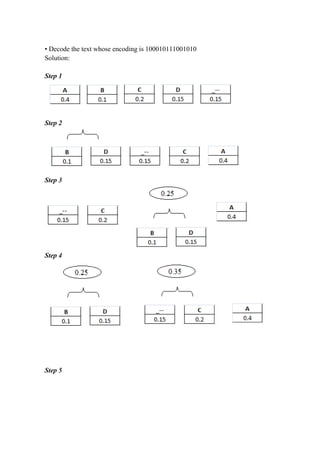

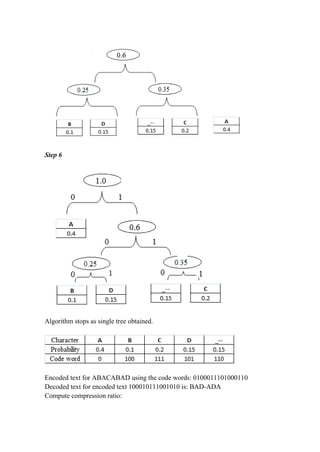

The document discusses greedy algorithms and matroids. It provides examples of problems that can be solved using greedy approaches, including sorting an array, the coin change problem, and activity selection. It defines key aspects of greedy algorithms like the greedy choice property and optimal substructure. Huffman coding is presented as an application that constructs optimal prefix codes. Finally, it introduces matroids as an abstract structure related to problems solvable by greedy methods.

![Greedy Activity Selector Algorithm

Greedy-Activity-Selector(s, f)

1. n ← length[s]

2. A ← {a1}

3. i ← 1

4. for m ← 2 to n

5. do if sm ≥ fi

6. then A ← A U {am}

7. i ← m

8. return A

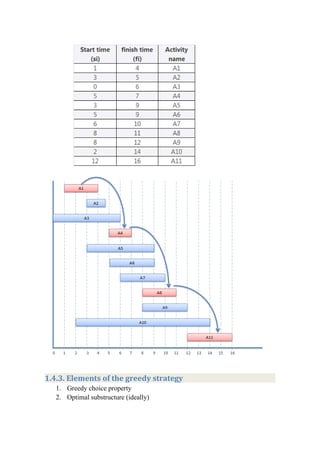

Example

Points to remember

For this algorithm we have a list of activities with their starting time

and finishing time.

Our goal is to select maximum number of non-conflicting activities that

can be performed by a person or a machine, assuming that the person or

machine involved can work on a single activity at a time.

Any two activities are said to be non-conflicting if starting time of one

activity is greater than or equal to the finishing time of the other

activity.

In order to solve this problem we first sort the activities as per their

finishing time in ascending order.

Then we select non-conflicting activities.

Problem

Consider the following 8 activities with their starting and finishing time.

Our goal is to find non-conflicting activities.

For this we follow the given steps

1. sort the activities as per finishing time in ascending order

2. select the first activity

3. select the new activity if its starting time is greater than or equal to the

previously selected activity

REPEAT step 3 till all activities are checked

Step 1: sort the activities as per finishing time in ascending order

Step 2: select the first activity

Step 3: select next activity whose start time is greater thanor equal to the finish

time of the previously selected activity](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/daachapter4-200419170136/85/Daa-chapter4-3-320.jpg)