This document is a handbook for school practitioners on developing curriculum. It provides conceptual frameworks and practical guidance. The handbook covers curriculum concepts, establishing school purpose and goals, selecting curriculum content, designing learning experiences and resources, and evaluating student learning. The intended audience is administrators, coordinators and teachers who are involved in curriculum development. The handbook aims to help these practitioners design curriculum that is relevant to their specific school contexts and can be effectively implemented in classrooms.

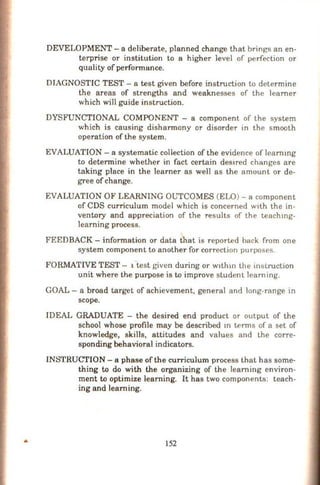

![the one hand, anrl the sciences, on the other, and the subdivisions

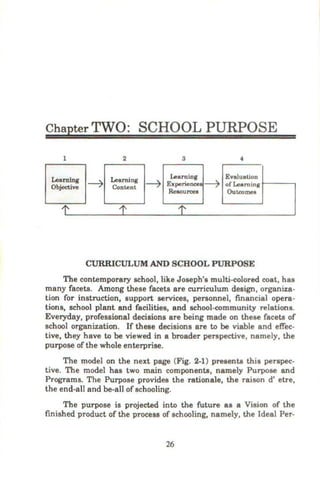

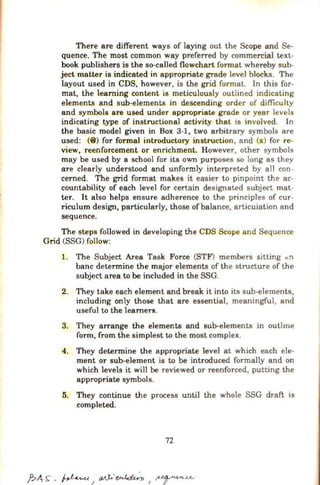

of these two branches. 'fhis fund has been accumulated over a long

period of time owing to man's unceasing exploration of hts world,

especially his four-way relationship<;: vertically, Wlth the Supreme

Being above him and with the physical world below; horizonLally,

with other men, on the one hand, and with himself, on the other

(Fig. 3-1).

GOD

i

metaphysical

t

--4 IMAN I~ [ - 4 10thcrM:]

i

physical

Physical

World

Fig. 3-1. Sources of Human Learning:

MaD's Four-Way Relalionahtpe

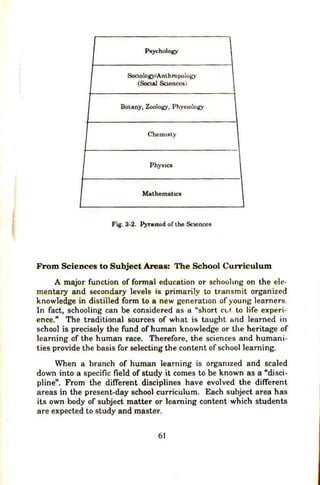

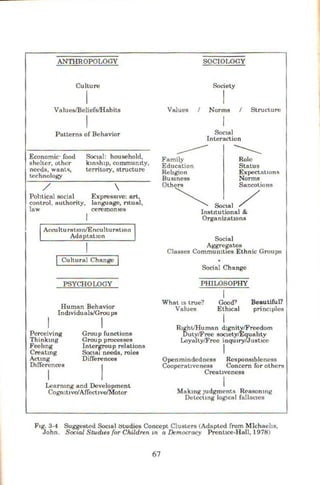

Chronologically speaking, the different organized branches of

human learning developed over time starting first with Mathemat-

ics, a man-made science, followed by the physical non-life sciences

(Physics and, Chemistry), then the life sciences (Botany, Zoology an

Physiology), then the Social Sciences (Sociology and Anthropology),

and finally, Psychology. The Social Sciences and Psychology consti-

tute what is popularly known as the behavioral sciences. Fig. 3-2

on the next page illustrates this development of the Sciences.

60](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/339186096-curriculum-development-system-jesus-c-palma-230821093240-37f4fc55/85/Curriculum-Development-System-Jesus-C-Palma-pdf-72-320.jpg)

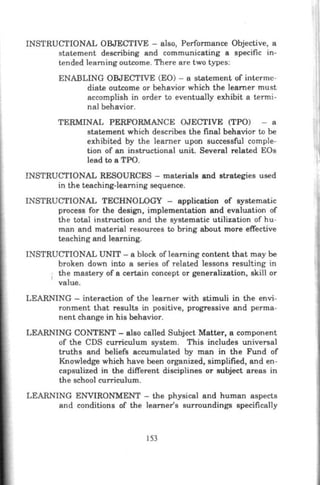

![Chapter FOUR: LEARNING -_$t~

EXPERIENCES AND

RESOURCES

1

1ng

~11m

ObjCClive ---7

2

Learrung

Content

1'

3 4

~a.mng1 Evaluation

--7 Experience --7 of Learning

Resources Outa>mea

1'

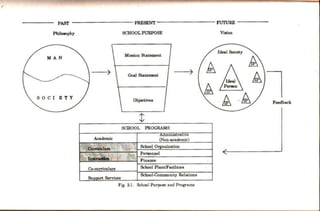

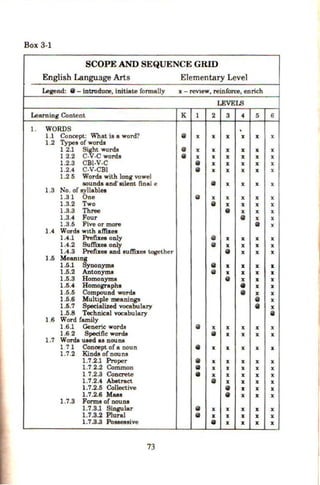

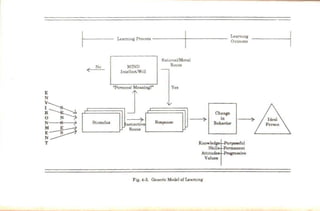

To attain its objectives, the school employs a body of content

and a set of learning experiences associated with the content.

"Learning content" and "learning experiences" are two differ-

ent things. The former refers to aspects of the environment or

reality that a person internalizes as parl of the repertoire he needs

for successful Jiving in society. This inc1udes information and

knowledge, concepts and beliefs, habits and skills, sensitivities and

altitudes, values and ideals prevalent in that society. The latter,

on the other hand, refers to certain activities that the learner un-

dergoes in reaction to the environment with which he has an oppor-

tumty to interact. An experience is persona] to the Ieamer and

what he gets out of it depends a lot on his total personal life space.

77](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/339186096-curriculum-development-system-jesus-c-palma-230821093240-37f4fc55/85/Curriculum-Development-System-Jesus-C-Palma-pdf-89-320.jpg)

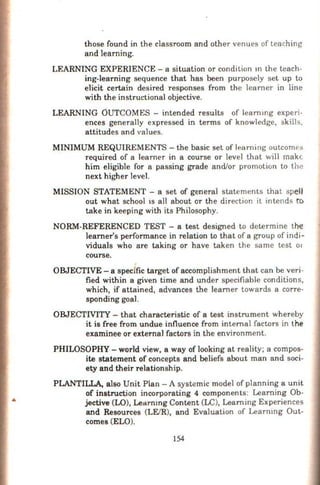

![The CIPP model is a wholistic, systemic approach to curncu-

lum evaluation. It takes into account all the components of the

program from incept10n to concluswn.

Context evaluation attempts to examine the nature of the

school population being served and their peculiar ecology. This

involves looking carefully at the nature of the students who are

the intended beneficiaries of the program, not just some vague

group of learners If the curriculum does not serve the actual

needs of the learners and the community, the prospects of its suc-

cess are d1m. Feedback from context evaluation enables the cur-

riculum developers to adJUbL program goals accordingly. It pro-

vides a kind of "reality te.st" that allows the school to ascertain the

validity of its assumptions about the learners and other aspects of

the environment in wh1ch the program operates.

The school also needs to look closely at the means bemg used

to meet the goals of the curnculum. Input evaluation is concerned

with the curriculum content spelled out in the curriculum bluepnnt

or master plan of instruction. The key question here is. Giveu the

goals and the available range of content options for meetmg tht>m ,

have we made the most appropFiate choice? Input evaluation then

attempts to validate the accuracy and adequacy of the cu.rn culum

and instructional des1gn m meetmg program goals.

Process evaluation is concerned with the mechanics of im

p]ementatlon. It looks at the program as it is being earned out

The idea 1s to assess the resources and strategies of the dehvery

package. The school has to reassure itself that the program IS on

track as des1gned. This is espec1ally crucial 10 a large-scale opera-

tion involving the whole school and so many teachers. This phase

calls for frequent and immed1ate feedback to and from those who

are part of the program. This will then enable the school to mtro-

duce contingent or corrective measures for the ongoing improve-

ment of the program.

~roduct evaluation is the last component of the CIPP evalu-

ation process. It answers the quest10n. When all is said and done,

were the goals of the curriculum ach1eved opttmally. This phase

occurs at the end of the program implementation. Data obtained m

this phase may be used as a basis for modifymg the design before

the program lS recycled.

147](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/339186096-curriculum-development-system-jesus-c-palma-230821093240-37f4fc55/85/Curriculum-Development-System-Jesus-C-Palma-pdf-159-320.jpg)

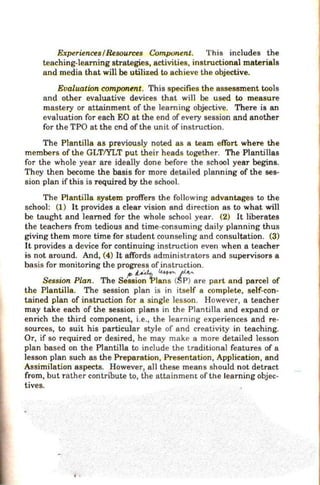

![0

Objectives, instructional

characteristics 44-49

classification 51-55

definiton 41

format 49-50

limitations 12-44

types 55-56

uses 42

Objectivity of a lest 116-117

Objective Type test 124, 125-

129

Overlaps in curriculum content

11,69

p

Performance standard 48

Persona] experience 77, 102

Personal meaning in learning

82

Philippine Association of Lan-

guage Teaching (PALT) 37

Philippine Social Science Coun-

cil (PSSC) 37

Philippine Society for Curricu-

lum Development (PSCD)

37

Philosophical screen for school

goals 38

Physical Education as a school

subject 62

PIE management model 15-18

Plantillas, also Unit Plans 17,

18, 21-22, 74-75, 85107

Presidental Commission to Sur-

vey Philippine Education

(PCSPE) 44

Proctoring a test 137

Production system 12-15

Promotion of students 118

Progress Assessment Rocord

(PAR) 17,18

Psychologival screen for school

goals 39-40

Q

Qualitative aspect of evaluation

114

Quality control in production

system 15, 140, 146

Quantitative aspect of evalu-

ation 114

Question-asking in teaching

and learning 100-101

Quiz 105,115

R

Readiness as a factor in learn-

ing 118

Realia 92

Reality or real world 92

Rehability of a test 116

Remediatiot. US

Representation of reality 92

Repetition principle in learning

102-103

Reproduction of reality 92

Resource persons 92

Reteaching 118

Retention of students 118

Rote learning 117

167](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/339186096-curriculum-development-system-jesus-c-palma-230821093240-37f4fc55/85/Curriculum-Development-System-Jesus-C-Palma-pdf-179-320.jpg)