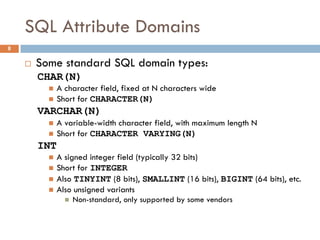

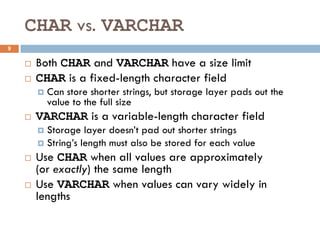

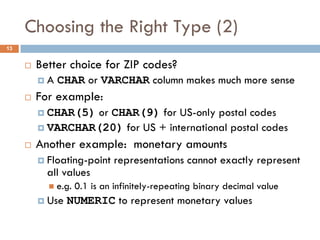

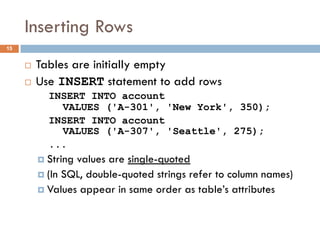

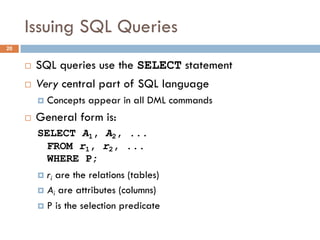

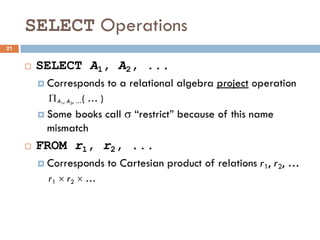

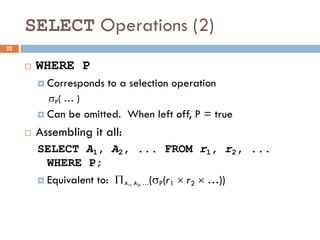

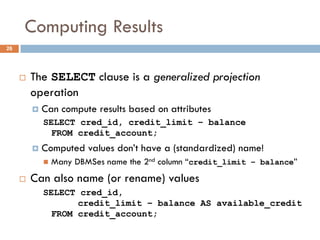

SQL is a language for working with relational databases and querying the data within them. It began as SEQUEL in the 1970s and has since been standardized into different versions by ANSI and ISO. SQL allows users to define schemas, manipulate data, and write complex queries across multiple tables. The document provides an overview of SQL's core functionality, including data definition, manipulation, basic syntax, and examples of common queries.