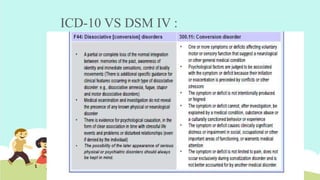

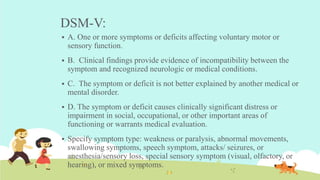

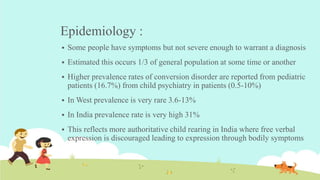

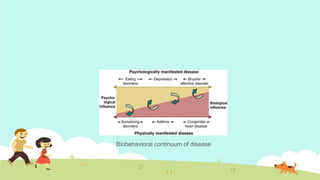

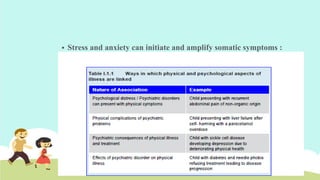

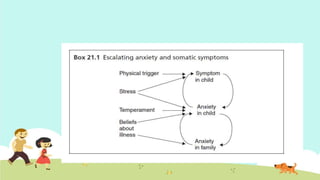

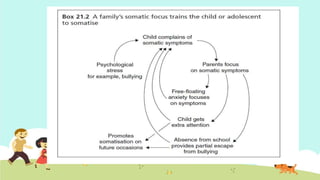

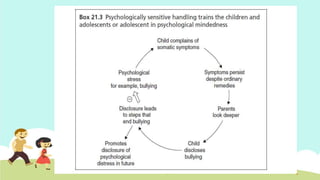

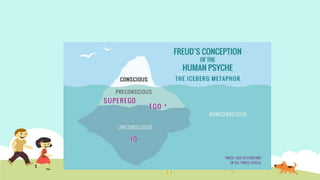

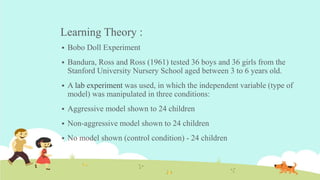

This document provides an overview of conversion disorder in children. It discusses the history and conceptualization of conversion disorder. Key points include: conversion disorder involves physical symptoms that cannot be explained by medical factors and may represent underlying psychological issues; it is more common in children and adolescents experiencing stressors or family dysfunction; learning from models and gaining secondary benefits can perpetuate symptoms; accurate diagnosis is important to guide appropriate treatment focusing on the underlying psychological needs rather than the physical symptoms.