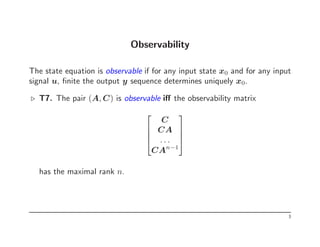

This document discusses controllability and observability in the context of closed-loop control systems. It defines controllability as the ability to transfer a system from one state to another using input signals, and observability as the ability to determine the system state from output measurements. The document presents theorems for determining controllability and observability based on system matrices. It also discusses how state estimators can be used to estimate unobservable states and how controllers can be designed using pole placement to achieve stability and reference signal tracking.

![Closed-loop control with state estimation

y[k]

u[k]

System

Controller

r[k]

Ĝ[z]

State

Estimator

The instability of a open loop controller is caused by gradual accumulation of

disturbances. The control signal becomes unsynchronised with the system.

⊲ If we can estimate the system state from the output, we can circumvent

such synchronisation errors. The system must be observable for that.

⊲ Even if we know the system state, it might be impossible to track the

reference signal. In brief, the system must be controllable.

1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/controllability-and-observability-221213170545-5e56123b/85/controllability-and-observability-pdf-3-320.jpg)

![Controllability

The state equation is controllable if for any input state x0 and for any final

state x1 there exists an input u that transfers x0 to x1 in a finite time.

⊲ T6. The n dimensional pair (A, B) is controllable iff the controllability

matrix

B AB A2

B An−1

B

has the maximal rank n.

The desired input can be computed from the system of linear equations

x1 = An

x0 + An−1

Bu[0] + An−2

Bu[1] + · · · + Bu[n − 1] .

Although the theorem T6 gives an explicit method for controlling the

system, it is an off-line algorithm with a time lag n.

A good controller design should yield a faster and more robust method.

2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/controllability-and-observability-221213170545-5e56123b/85/controllability-and-observability-pdf-4-320.jpg)

![Offline state estimation algorithm

Again, the input state x0 can be computed from a system of linear equations

y[0] = Cx0 + Du[0]

y[1] = CAx0 + CBu[0] + Du[1]

· · ·

y[n − 1] = CAn−1

x0 + · · · + CBu[n − 2] + Du[n − 1]

Although this equation allows us to find out the state of the system, it is

offline algorithm, which provides a state estimation with a big time lag.

A good state space estimator must be fast and robust.

4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/controllability-and-observability-221213170545-5e56123b/85/controllability-and-observability-pdf-6-320.jpg)

![General structure of state estimators

y[k]

u[k] System

State Estimator

x̂[k]

x[k] = Ax[k − 1] + Bu[k − 1]

y[k] = Cx[k] + Du[k]

A state estimate x̂[k] is updated according to u[k] and y[k]:

⊲ Update rules are based on linear operations.

⊲ The state estimator must converge quickly to the true value x[k]

⊲ The state estimator must tolerate noise in the inputs u[k] and y[k].

5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/controllability-and-observability-221213170545-5e56123b/85/controllability-and-observability-pdf-7-320.jpg)

![Example

Consider a canonical realisation of the transfer function ĝ[z] = 0.5z+0.5

z2−0.25

A =

0 0.25

1 0

B =

1

0

C = [0.5 0.5] D = 0

Then a possible stable state estimator is following

x̂[k + 1] = Ax̂[k] + Bu[k] + 1(y[k] − Cx̂[k]

| {z }

ŷ[k]

) .

In general, the feedback vector 1 can be replaced with any other vector to

increase the stability of a state estimator.

6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/controllability-and-observability-221213170545-5e56123b/85/controllability-and-observability-pdf-8-320.jpg)

![Equivalent state equations

Two different state descriptions of linear systems

(

x[k + 1] = A1x[k] + B1u[k]

y[k] = C1x[k] + D1u[k]

(

x[k + 1] = A2x[k] + B2u[k]

y[k] = C2x[k] + D2u[k]

are equivalent if for any initial state x0 there exists an initial state x0 such

that for any input u both systems yield the same output and vice versa.

⊲ T8. Two state descriptions are (algebraically) equivalent if there exists

an invertible matrix P such that

A2 = P A1P −1

B2 = P B1

C2 = C1P −1

D2 = D1 .

7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/controllability-and-observability-221213170545-5e56123b/85/controllability-and-observability-pdf-10-320.jpg)

![Kalman decomposition

⊲ T9. Every state space equation can be transformed into an equivalent

description to a canonical form

xco[k + 1]

xco[k + 1]

xco[k + 1]

xco[k + 1]

=

Aco 0 A13 0

A21 Aco A23 A24

0 0 Aco 0

0 0 A43 Aco

xco[k]

xco[k]

xco[k]

xco[k]

+

Bco

Bco

0

0

u[k]

y[k] = [Cco 0 Cco 0] x[k] + Du[k]

where

⋄ xco is controllable and observable

⋄ xco is controllable but not observable

⋄ xco is observable but not controllable

⋄ xco is neither controllable nor observable

9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/controllability-and-observability-221213170545-5e56123b/85/controllability-and-observability-pdf-12-320.jpg)

![Minimal realisation

⊲ T10. All minimal realisations are controllable and observable. A

realisation of a proper transfer function ĝ[z] = N(z)/D(z) is minimal iff

it state space dimension dim(x0) = deg D(z).

10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/controllability-and-observability-221213170545-5e56123b/85/controllability-and-observability-pdf-13-320.jpg)

![General setting

According to Kalman decomposition theorem, the state variables can be

divided into four classes depending on controllability and observability.

⊲ We cannot do anything with non-controllable state variables.

⊲ Non-observable variables can be controlled only if they are marginally

stable. We can do it with an open-loop controller.

⊲ For controllable and observable state variables, we can build effective

closed-loop controllers.

Simplifying assumptions

⊲ From now on, we assume that we always want to control state variables

that are both controllable and directly observable: y[k] = x[k].

⊲ If this is not the case, then we must use state estimators to get an

estimate of x. The latter just complicates the analysis.

11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/controllability-and-observability-221213170545-5e56123b/85/controllability-and-observability-pdf-15-320.jpg)

![Unity-feedback configuration

y[k]

u[k] System

Controller

r[k]

ĝ[z]

Ĉ[z]

p +

-1

Design tasks

⊲ Find a compensator ĉ[z] such that system becomes stable.

⊲ Find a proper value of p such that system starts to track reference signal.

It is sometimes impossible to find p such that y[k] ≈ r[k].

⊲ The latter is impossible if ĝ[1] = 0, then the output y[k] just dies out.

12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/controllability-and-observability-221213170545-5e56123b/85/controllability-and-observability-pdf-16-320.jpg)

![Overall transfer function

Now note that

ŷ = ĝ[z]ĉ[z](pr̂ − ŷ) ⇐⇒ ŷ =

pĝ[z]ĉ[z]

1 + ĝ[z]ĉ[z]

r̂

and thus the configuration is stable when the new transfer function

ĝ◦[z] =

pĝ[z]ĉ[z]

1 + ĝ[z]ĉ[z]

has poles lying in the unit circle. Now observe

ĝ[z] =

N(z)

D(z)

, ĉ[z] =

B(z)

A(z)

=⇒ ĝ◦[z] =

pB(z)N(z)

A(z)D(z) + B(z)N(z)

13](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/controllability-and-observability-221213170545-5e56123b/85/controllability-and-observability-pdf-17-320.jpg)

![Pole placement

We can control the denominator of the new transfer function ĝ◦[z]. Let

F(z) = A(z)D(z) + B(z)N(z)

be a desired new denominator. Then there exists polynomials A(z) and

B(z) for every polynomial F(z) provided that D(z) and N(z) are coprime.

The degrees of the polynomials satisfy deg B(z) ≥ deg F(z) − deg D(z).

ℑ(s)

ℜ(s)

BIBO

stable

ℜ(z)

ℑ(z)

BIBO

stable

14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/controllability-and-observability-221213170545-5e56123b/85/controllability-and-observability-pdf-18-320.jpg)

![Signal tracking properties

Let ĝ◦[z] be the overall transfer function.

⊲ The system stabilises if ĝ◦[z] is BIBO stable.

⊲ The system can track a constant signal r[k] ≡ a if ĝ◦[1] = 1.

⊲ The system can track a ramp signal r[k] ≡ ak if ĝ◦[1] = 1 and ĝ′

◦[1] = 0.

The latter follows from the asymptotic convergence

y[k] → aĝ′

◦[1] + kaĝ◦[1]

for an input signal r[k] = ak. Moreover, let ĝ◦ = N(z)/D(z). Then

ĝ◦[1] = 1 ∧ ĝ′

◦[1] = 0 ⇐⇒ N(1) = D(1) ∧ N′

(1) = D′

(1) .

15](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/controllability-and-observability-221213170545-5e56123b/85/controllability-and-observability-pdf-19-320.jpg)

![Illustrative example

Consider a feedback loop with the transfer function g[z] = 1

z−2. Then we

can try many different pole placements

F(z) ∈

z − 0.5, z + 0.5, z2

− 0.25, z2

+ z + 0.25, z2

− z + 0.25

The corresponding compensators are

ĉ[z] ∈

3

2

,

5

2

,

15

4z + 8

,

24

4z + 12

,

9

4z + 4

,

p ∈

1

3

,

3

5

,

1

5

, ,

9

25

,

1

9

.

They can be found systematically by solving a system of linear equations.

17](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/controllability-and-observability-221213170545-5e56123b/85/controllability-and-observability-pdf-21-320.jpg)

![Robust signal tracking

Sometimes the system changes during the operation. The latter can be

modelled as an additional additive term w[k] in the input signal.

If we know the poles of reference signal r[k] and w[k] ahead, then we can

design a compensator that filters out the error signal w[k].

For instance, if w[k] is a constant bias, then adding an extra pole 1

z−1

cancels out the effect of bias. See pages 277–283 for further examples.

In our example, the robust compensator for F[z] = z2

− 0.25 is

ĉ[z] =

12z − 9

4z − 4

p = 1 .

18](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/controllability-and-observability-221213170545-5e56123b/85/controllability-and-observability-pdf-22-320.jpg)

![Model matching

Find a feedback configuration such that ĝ◦ is BIBO stable and ĝ◦[1] = 1.

y[k]

u[k] System

r[k]

ĝ[z]

Controller

ĉ1[z]

+

ĉ2[z]

Feedback

⊲ The two-parameter configuration described above provides more flexibility

and it is possible to cancel out zeroes that prohibit tracking.

⊲ There are many alternative configurations. A controller design is

acceptable if every closed-loop configuration is BIBO stable.

19](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/controllability-and-observability-221213170545-5e56123b/85/controllability-and-observability-pdf-23-320.jpg)