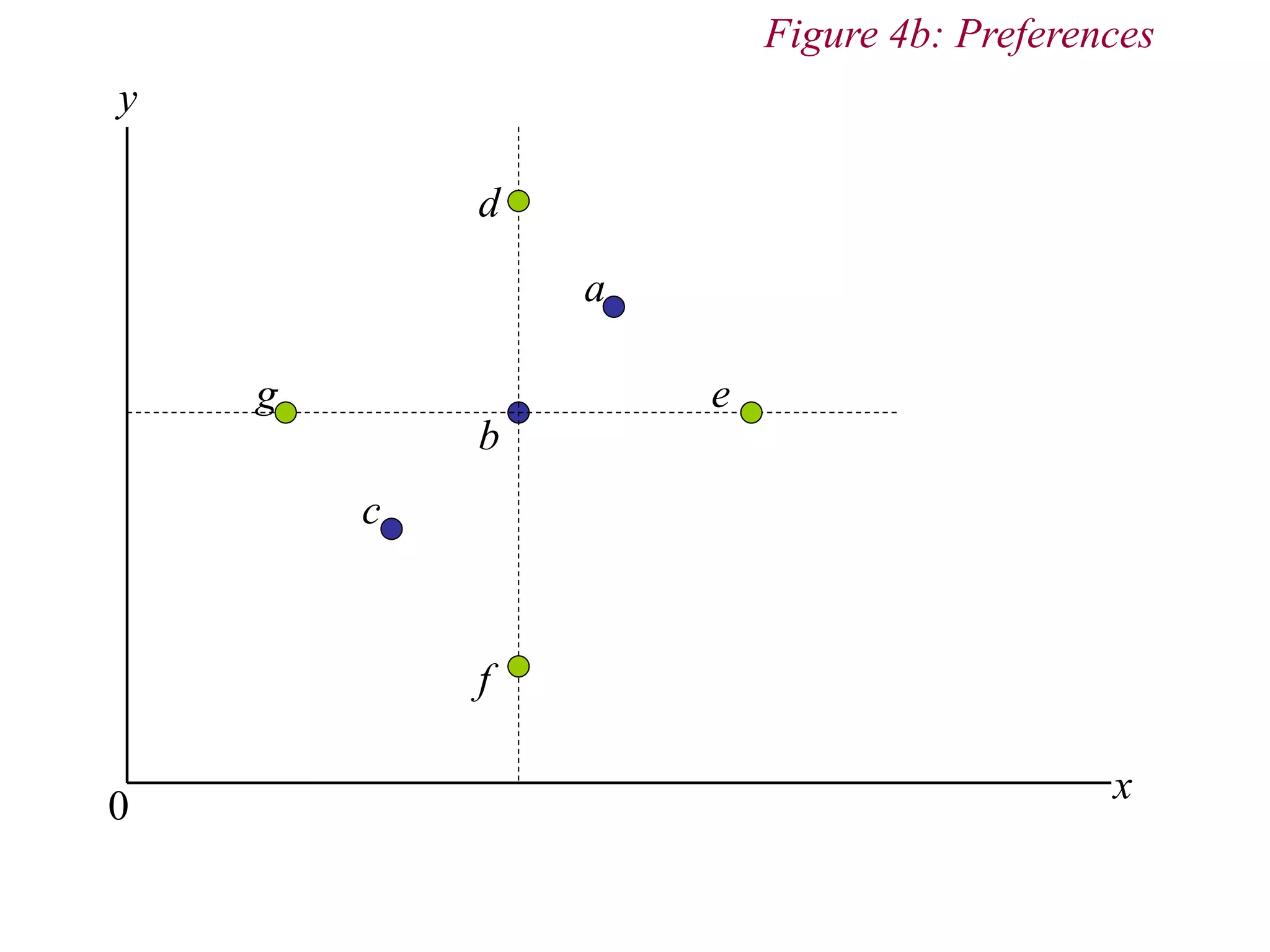

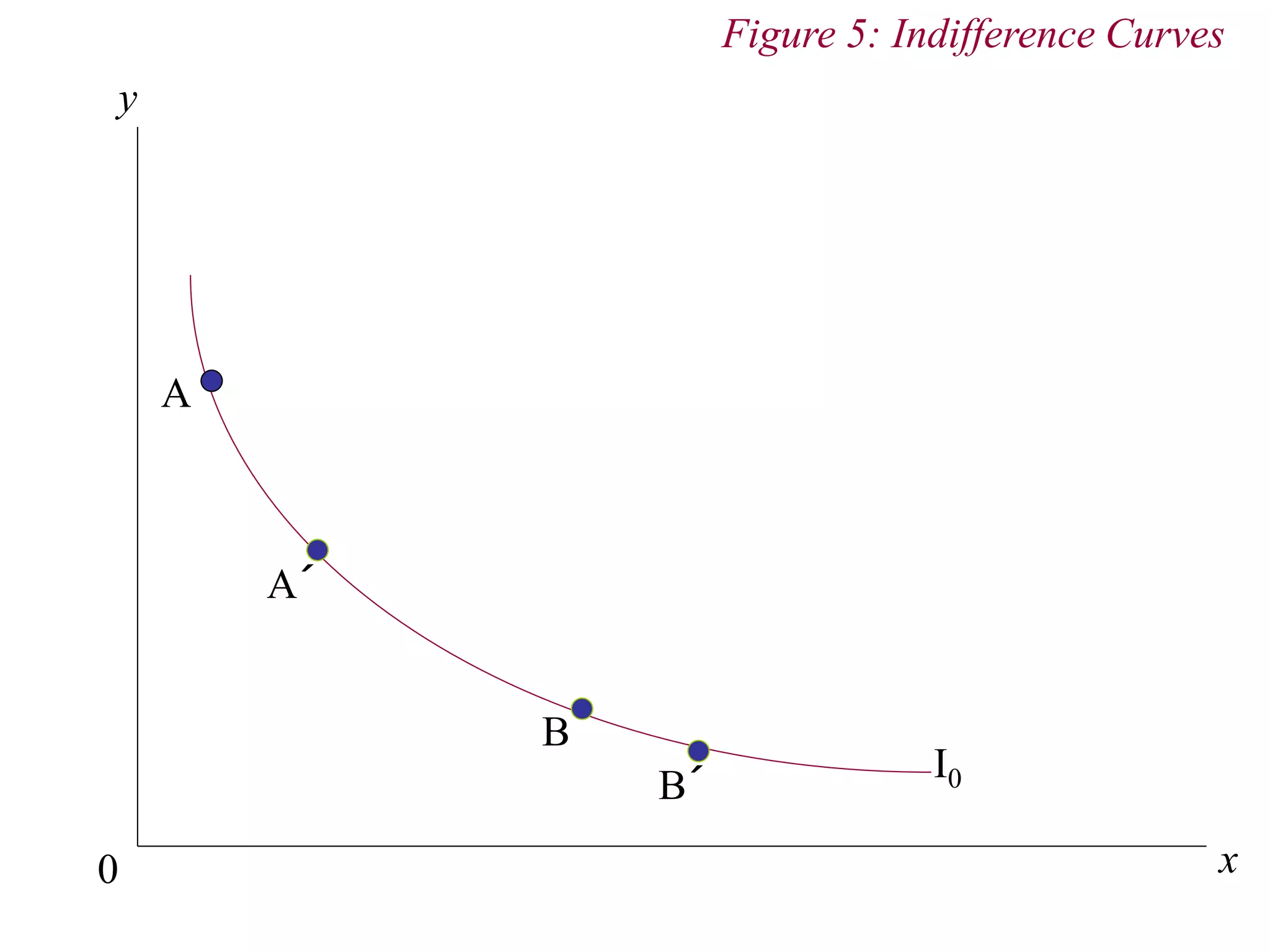

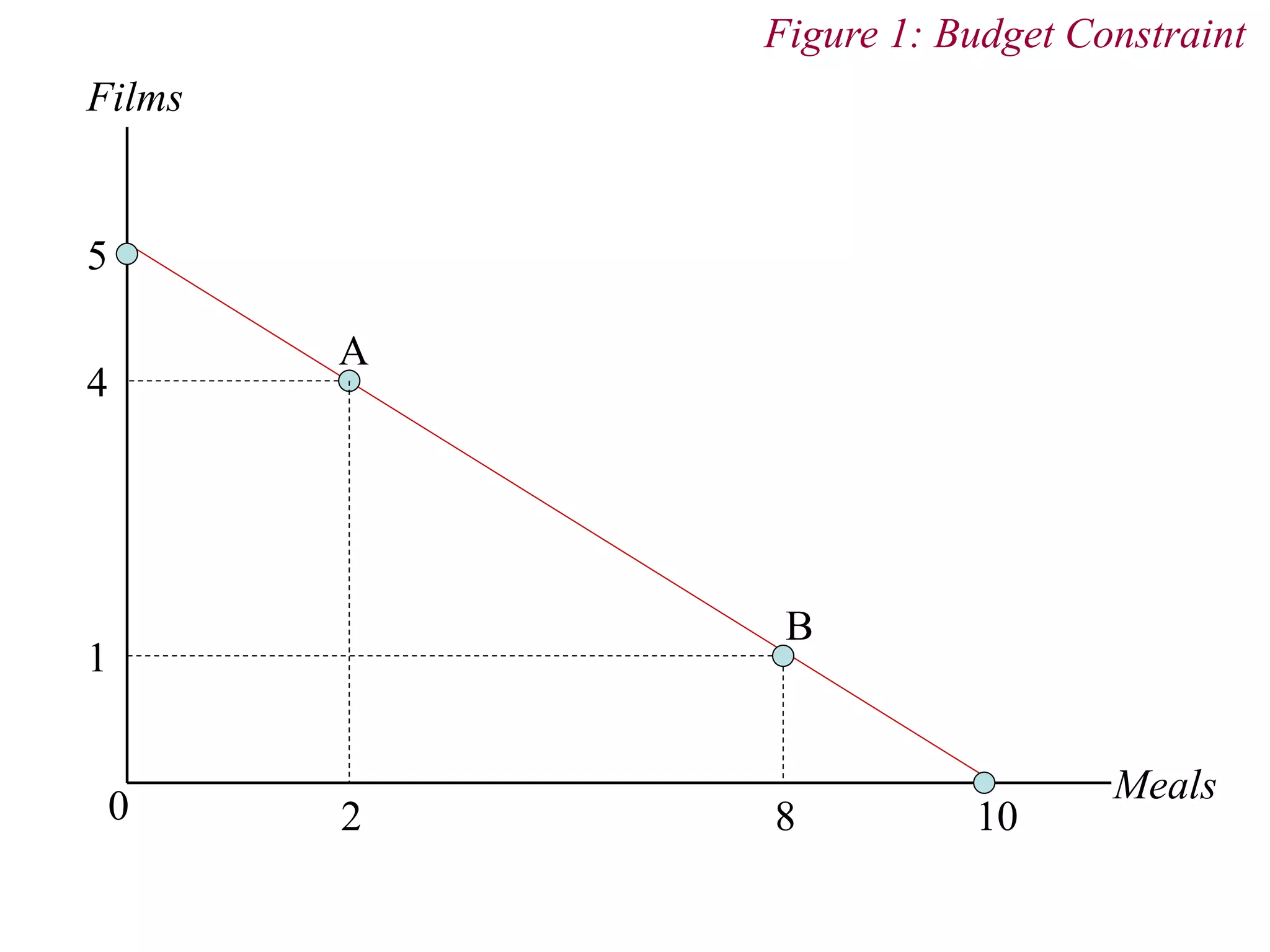

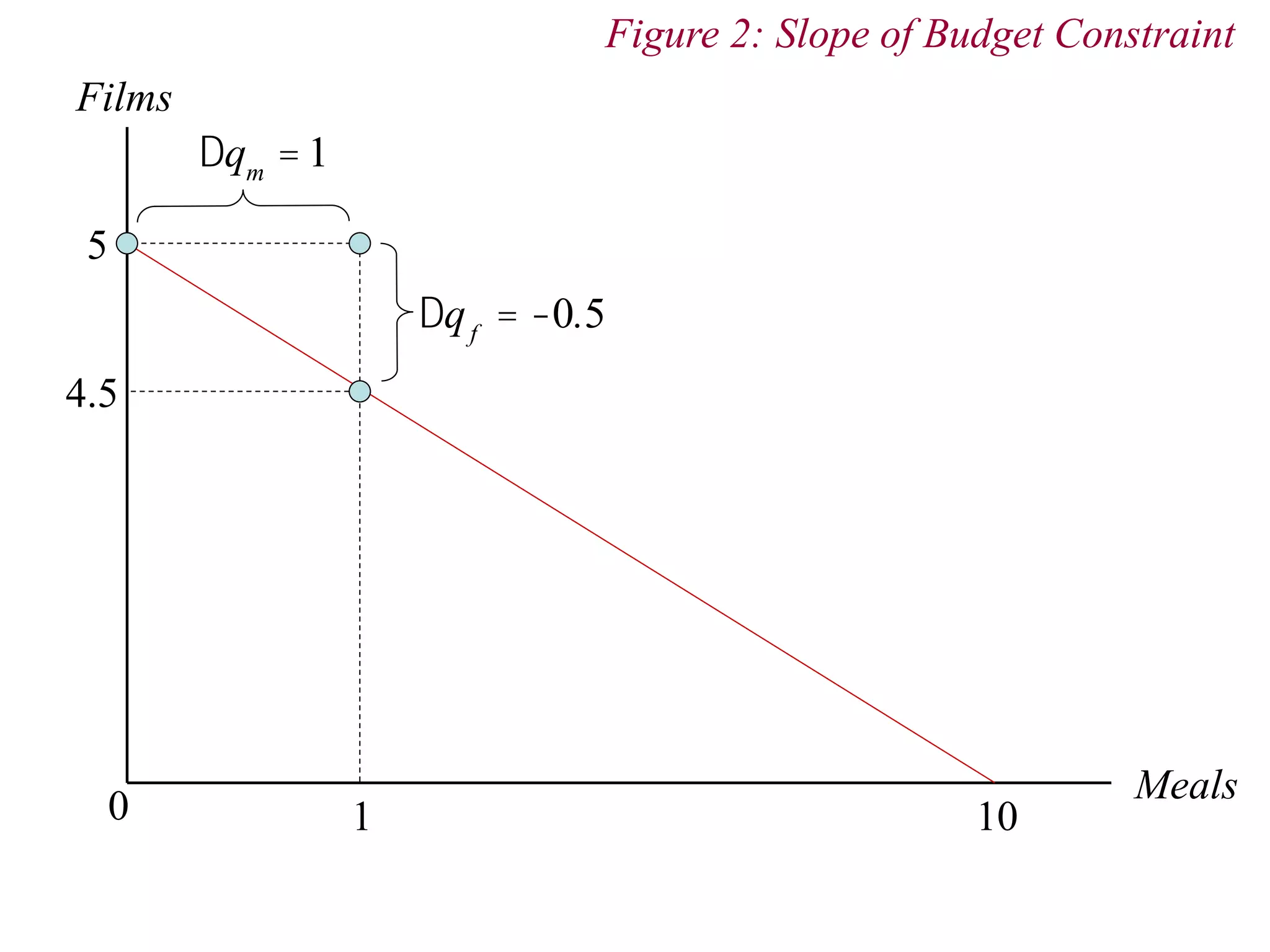

The document provides an overview of consumer theory and the budget constraint in microeconomics. It discusses how consumers maximize utility given their preferences for goods and a budget constraint determined by income and prices. Specifically, it defines the budget constraint graphically using indifference curves, explains how the slope of the budget line represents the trade-off between goods, and discusses how taxes, subsidies and rationing can impact the budget constraint. It also outlines the key assumptions of consumer preferences including completeness, consistency, non-satiation, and diminishing marginal rate of substitution.

![3. Budget Constraint

Taxes and Subsidies

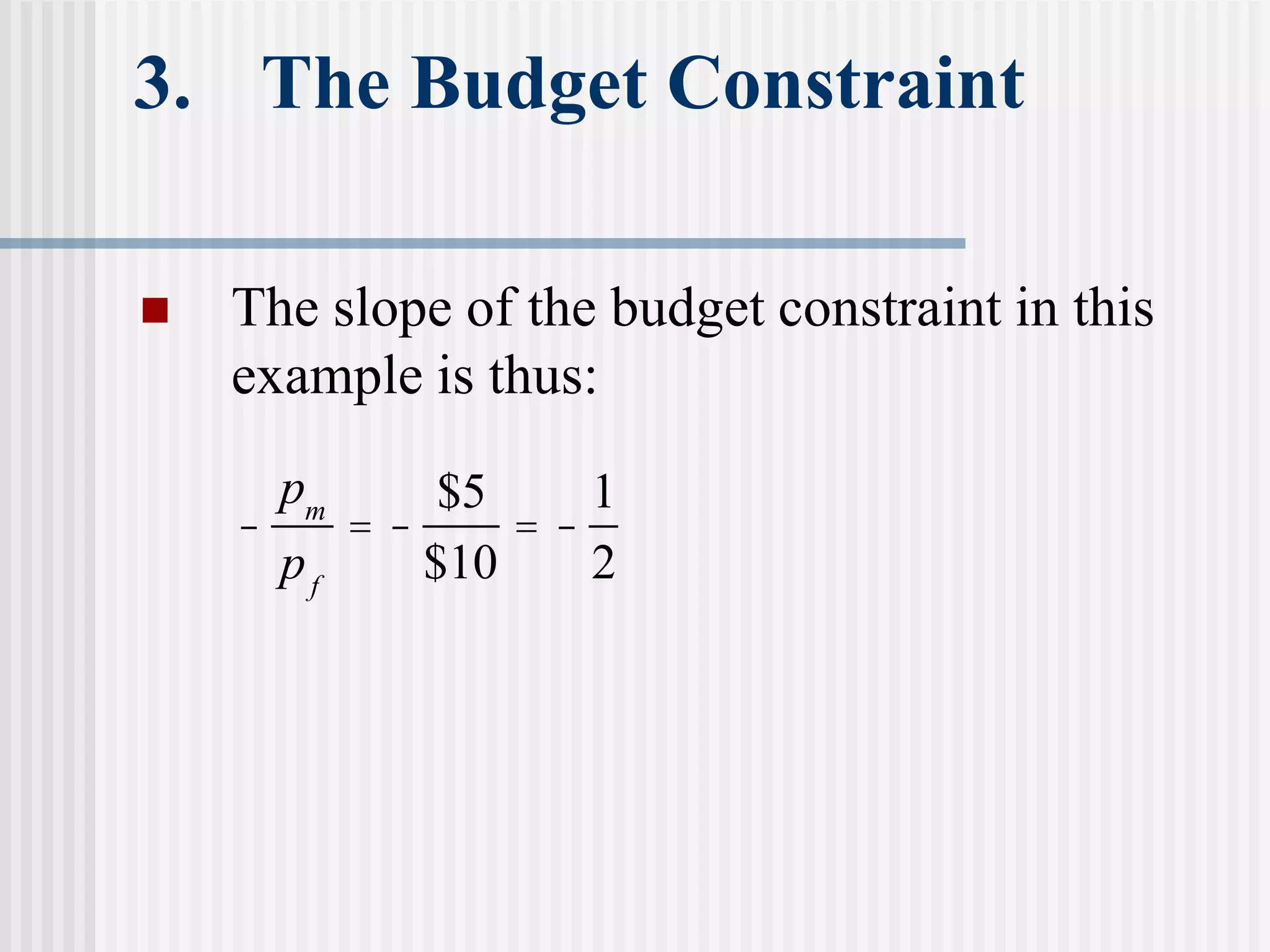

Taxes can be imposed per unit (i.e. p + t) or ad

valorem [i.e. p(1+ t)]

Subsidies are ‘negative’ taxes

Rationing causes budget constraint to become

vertical or horizontal](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/consumertheory1-221026062023-be6c0348/75/Consumer-Theory-1-ppt-22-2048.jpg)

![y

0 xt m/px

Figure 5: Budget Constraint and Taxation

m/py

x

Slope = -(px/py)

Slope = -[(px+t)/py]

x](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/consumertheory1-221026062023-be6c0348/75/Consumer-Theory-1-ppt-24-2048.jpg)