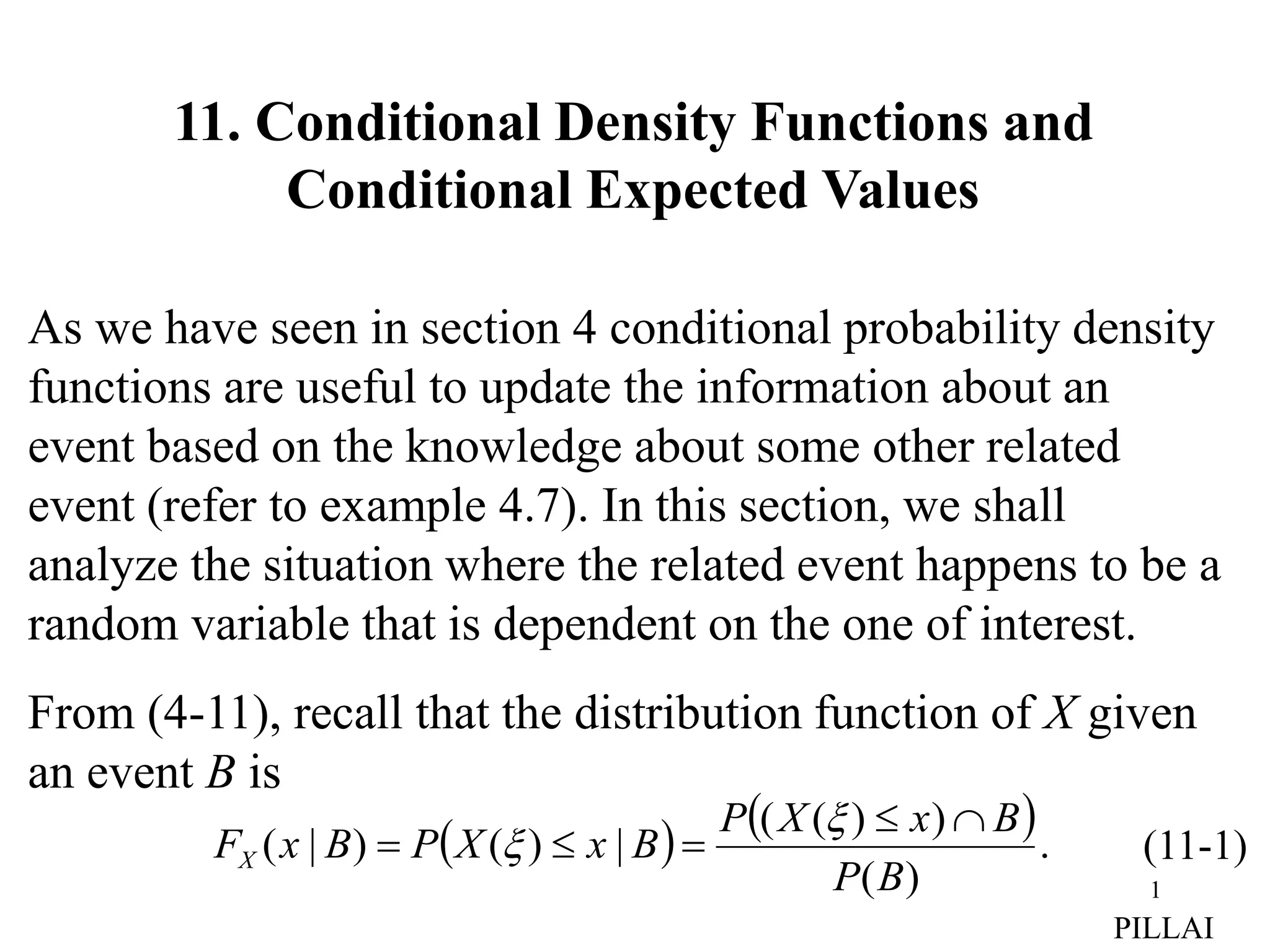

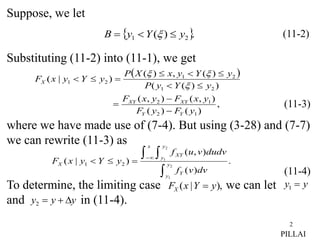

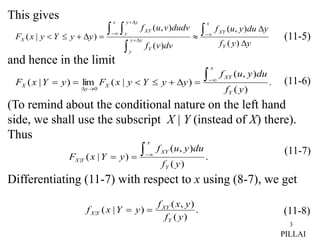

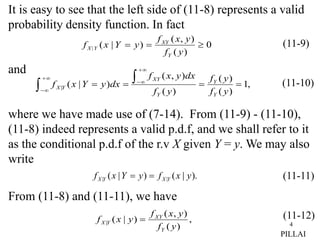

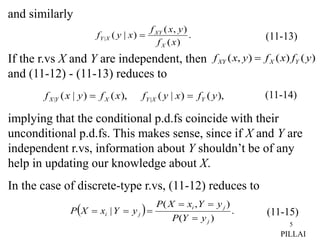

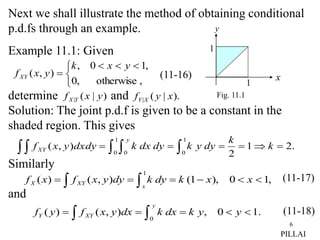

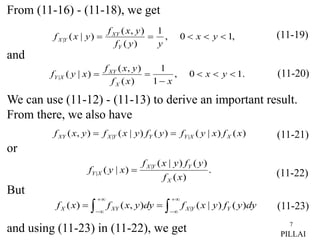

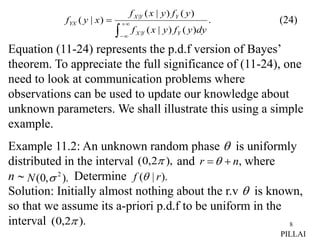

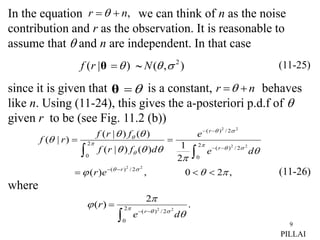

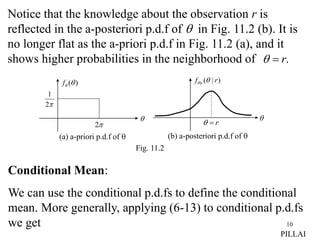

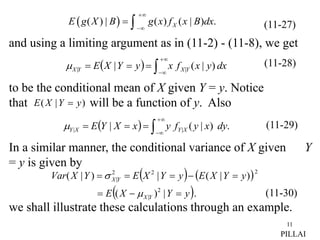

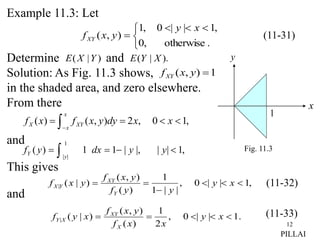

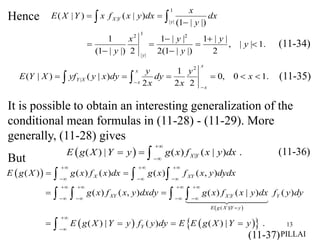

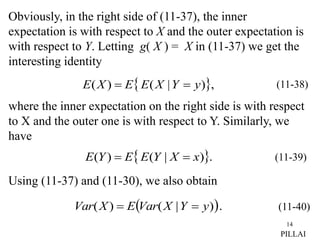

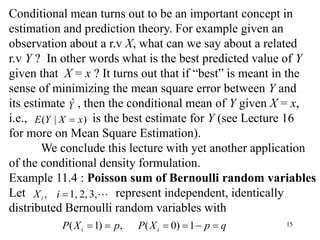

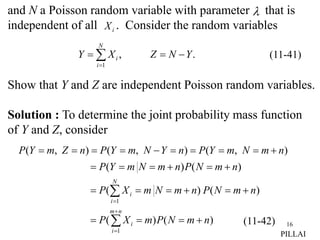

The document discusses conditional probability density functions and conditional expected values. It defines the conditional probability density function of a random variable X given another random variable Y=y as f(x|y). This allows updating knowledge about X based on information about Y. The conditional expected value of X given Y=y is defined as the integral of xf(x|y)dx. An example calculates the conditional PDFs and expected value for two random variables with a given joint PDF.