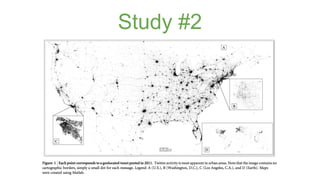

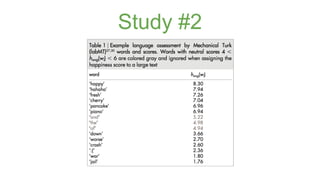

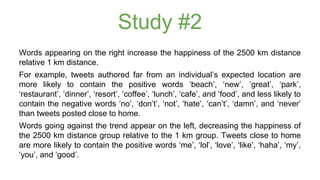

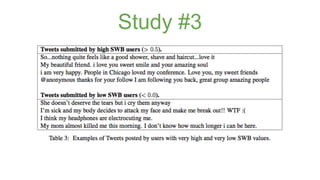

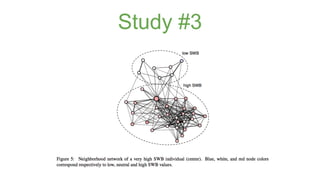

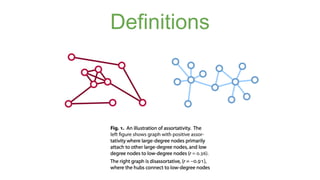

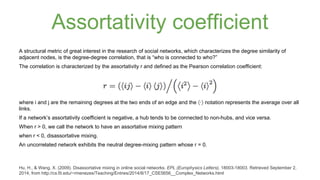

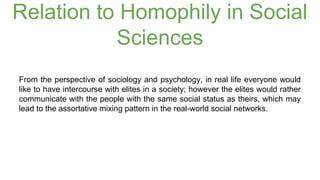

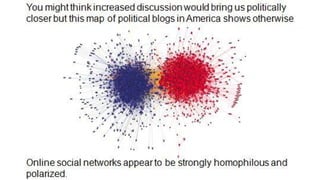

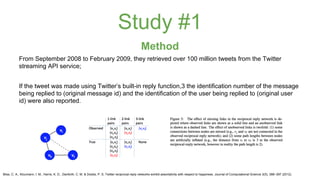

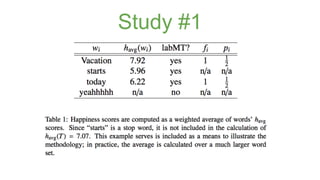

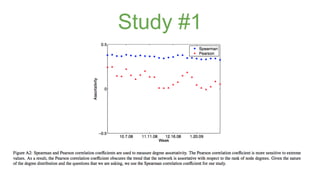

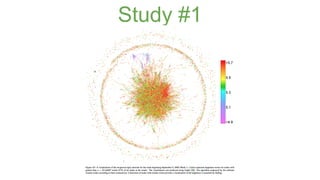

The document discusses assortativity and dissortativity in complex networks. It defines assortativity as "nodes with similar degree connect preferably" and dissortativity as "nodes with low degree try to connect with highly connected nodes." Several studies are summarized that examine assortativity in social networks like Twitter. Happiness was found to be assortative in Twitter reciprocal reply networks. Distance from one's typical location on Twitter was also found to correlate with expressed happiness levels. Assortative networks are described as being more resilient to attacks while disassortative networks are more vulnerable.

![Study #1

In a study of over 6 million users, Cha et al. [10] found that users with the

highest follower counts were not the users whose messages were most

frequently retweeted. This suggests that such popular users (as measured by

follower count) may not be the most influential in terms of spreading

information, and this calls into question the extent to which users are influenced

by those that they follow.

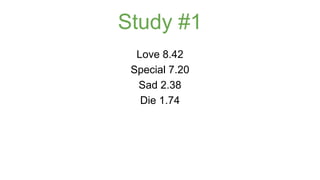

Large degree nodes use words such as “you,” “thanks,” and “lol” more

frequently than small degree nodes, while the latter group uses words such as

“damn,” “hate,” and “tired” more frequently.

Bliss, C. A., Kloumann, I. M., Harris, K. D., Danforth, C. M. & Dodds, P. S. Twitter reciprocal reply networks exhibit assortativity with respect to happiness. Journal of Computational Science 3(5), 388–397 (2012).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/complexnetworks-140916201243-phpapp01/85/Complex-networks-Assortativity-27-320.jpg)