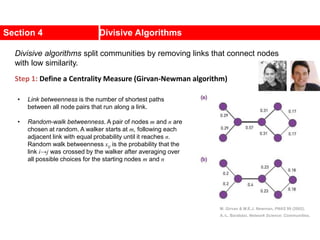

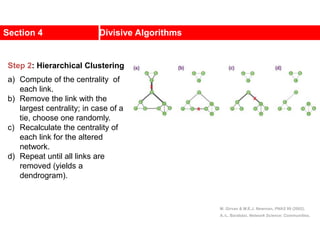

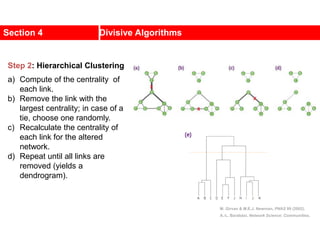

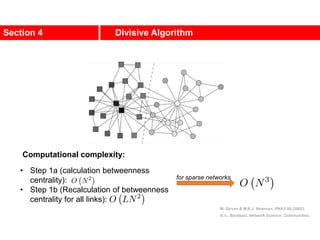

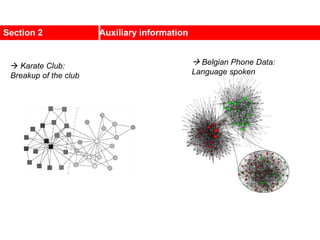

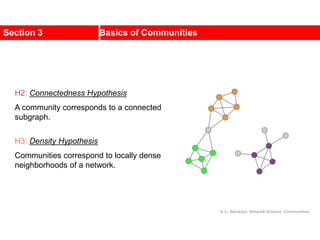

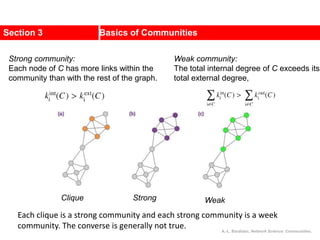

This document discusses Zachary's karate club network, which is a classic social network dataset. It contains three key points:

1. Zachary's karate club network describes the social ties between 34 members of a university karate club that split into two groups due to a conflict. This network is often used as an example for detecting community structure in networks.

2. The network was studied by Wayne Zachary from 1970-1972 and captured who interacted with whom both inside and outside the club. It correctly identified which group each member joined after the split except for one member.

3. The network became popular for studying community detection algorithms after being used in a 2002 paper by Michelle Girvan and Mark

![A social network of a karate club was studied by Wayne

W. Zachary for a period of three years from 1970 to

1972.[2]

The network captures 34 members of a karate club,

documenting links between pairs of members who

interacted outside the club.

During the study a conflict arose between the

administrator "John A" and instructor "Mr. Hi"

(pseudonyms), which led to the split of the club into

two.

Half of the members formed a new club around Mr. Hi;

members from the other part found a new instructor or

gave up karate.

Based on collected data Zachary correctly assigned all

but one member of the club to the groups they actually

joined after the split.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ch-9communities-220816124612-4745b556/85/Communities-in-Network-Science-3-320.jpg)

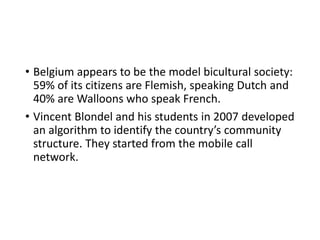

![Communities in Metabolic Networks

The E. coli metabolism offers a community structure of biological

systems [11].

a.The biological modules (communities) identified by the Ravasz

algorithm [11] (SECTION 9.3). The color of each node, capturing

the predominant biochemical class to which it belongs, indicates

that different functional classes are segregated in distinct

network neighborhoods. The highlighted region selects the nodes

that belong to the pyrimidine metabolism, one of the predicted

communities.

b.The topologic overlap matrix of the E. coli metabolism and the

corresponding dendrogram that allows us to identify the modules

shown in (a). The color of the branches reflect the predominant

biochemical role of the participating molecules, like

carbohydrates (blue), nucleotide and nucleic acid metabolism

(red), and lipid metabolism (cyan).

c.The red right branch of the dendrogram tree shown in (b),

highlighting the region corresponding to the pyridine module.

d.The detailed metabolic reactions within the pyrimidine module.

The boxes around the reactions highlight the communities

predicted by the Ravasz algorithm.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ch-9communities-220816124612-4745b556/85/Communities-in-Network-Science-9-320.jpg)

![Kernighan-Lin (KL) Example

a

b

c

d

e

f

g

h

4 { a, e } -2

0 -- 0

1 { d, g } 3

2 { c, f } 1

3 { b, h } -2

Step No. Vertex Pair Gain

5

5

2

1

3

Cut-cost

[©Sarrafzadeh]

Gain sum

0

3

4

2

0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ch-9communities-220816124612-4745b556/85/Communities-in-Network-Science-34-320.jpg)

![Kernighan-Lin (KL) Example

a

b c

d

e

f

g

h

4 { a, e } -2

0 -- 0

1 { d, g } 3

2 { c, f } 1

3 { b, h } -2

Step No. Vertex Pair Gain

5

5

2

1

3

Cut-cost

[©Sarrafzadeh]

Gain sum

0

3

4

2

0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ch-9communities-220816124612-4745b556/85/Communities-in-Network-Science-35-320.jpg)

![Internal

cost

GA

GB

a1

a2

an

ai

a3

a5 a6

a4

b2

bj

b4 b3

b1

b6

b7

b5

A

x B

y

y

b

x

b

b

b

b

a

a

a

j

j

j

j

j

i

i

i

C

C

I

E

D

I

E

D

Likewise,

[©Kang]

External

cost

B

y

y

a

a

A

x

x

a

a i

i

i

i

C

E

C

I ,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ch-9communities-220816124612-4745b556/85/Communities-in-Network-Science-37-320.jpg)

![• Lemma: Consider any ai A, bj B.

If ai, bj are interchanged, the gain is

• Proof:

Total cost before interchange (T) between A and B

Total cost after interchange (T’) between A and B

Therefore

Gain Calculation (cont.)

j

i

j

i b

a

b

a C

D

D

g 2

[©Kang]

others)

all

for

cost

(

j

i

j

i b

a

b

a C

E

E

T

others)

all

for

cost

(

j

i

j

i b

a

b

a C

I

I

T

j

i

j

j

i

i b

a

b

b

a

a C

I

E

I

E

T

T

g 2

i

a

D j

b

D](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ch-9communities-220816124612-4745b556/85/Communities-in-Network-Science-38-320.jpg)

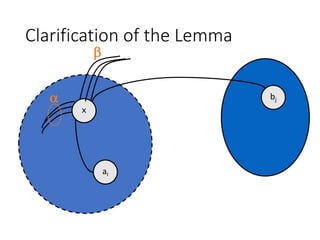

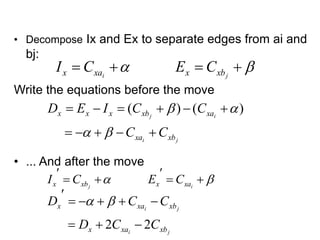

![Gain Calculation (cont.)

• Lemma:

• Let Dx’, Dy’ be the new D values for elements of

A - {ai} and B - {bj}. Then after interchanging ai & bj,

• Proof:

• The edge x-ai changed from internal in Dx to external in Dx’

• The edge y-bj changed from internal in Dx to external in Dx’

• The x-bj edge changed from external to internal

• The y-ai edge changed from external to internal

• More clarification in the next two slides

}

{

,

2

2

}

{

,

2

2

j

ya

yb

y

y

i

xb

xa

x

x

b

B

y

C

C

D

D

a

A

x

C

C

D

D

i

j

j

i

[©Kang]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ch-9communities-220816124612-4745b556/85/Communities-in-Network-Science-39-320.jpg)

![Example: KL

• Step 1 - Initialization

A = {2, 3, 4}, B = {1, 5, 6}

A’ = A = {2, 3, 4}, B’ = B = {1, 5, 6}

• Step 2 - Compute D values

D1 = E1 - I1 = 1-0 = +1

D2 = E2 - I2 = 1-2 = -1

D3 = E3 - I3 = 0-1 = -1

D4 = E4 - I4 = 2-1 = +1

D5 = E5 - I5 = 1-1 = +0

D6 = E6 - I6 = 1-1 = +0

[©Kang]

5

6

4 2 1

3

Initial partition

4

5

6

2

3

1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ch-9communities-220816124612-4745b556/85/Communities-in-Network-Science-42-320.jpg)

![Example: KL (cont.)

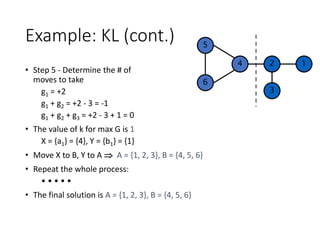

• Step 3 - compute gains

g21 = D2 + D1 - 2C21 = (-1) + (+1) - 2(1) = -2

g25 = D2 + D5 - 2C25 = (-1) + (+0) - 2(0) = -1

g26 = D2 + D6 - 2C26 = (-1) + (+0) - 2(0) = -1

g31 = D3 + D1 - 2C31 = (-1) + (+1) - 2(0) = 0

g35 = D3 + D5 - 2C35 = (-1) + (0) - 2(0) = -1

g36 = D3 + D6 - 2C36 = (-1) + (0) - 2(0) = -1

g41 = D4 + D1 - 2C41 = (+1) + (+1) - 2(0) = +2

g45 = D4 + D5 - 2C45 = (+1) + (+0) - 2(+1) = -1

g46 = D4 + D6 - 2C46 = (+1) + (+0) - 2(+1) = -1

• The largest g value is g41 = +2

interchange 4 and 1 (a1, b1) = (4, 1)

A’ = A’ - {4} = {2, 3}

B’ = B’ - {1} = {5, 6} both not empty

[©Kang]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ch-9communities-220816124612-4745b556/85/Communities-in-Network-Science-43-320.jpg)

![Example: KL (cont.)

• Step 4 - update D values of node connected to vertices (4, 1)

D2’ = D2 + 2C24 - 2C21 = (-1) + 2(+1) - 2(+1) = -1

D5’ = D5 + 2C51 - 2C54 = +0 + 2(0) - 2(+1) = -2

D6’ = D6 + 2C61 - 2C64 = +0 + 2(0) - 2(+1) = -2

• Assign Di = Di’, repeat step 3 :

g25 = D2 + D5 - 2C25 = -1 - 2 - 2(0) = -3

g26 = D2 + D6 - 2C26 = -1 - 2 - 2(0) = -3

g35 = D3 + D5 - 2C35 = -1 - 2 - 2(0) = -3

g36 = D3 + D6 - 2C36 = -1 - 2 - 2(0) = -3

• All values are equal;

arbitrarily choose g36 = -3 (a2, b2) = (3, 6)

A’ = A’ - {3} = {2}, B’ = B’ - {6} = {5}

New D values are:

D2’ = D2 + 2C23 - 2C26 = -1 + 2(1) - 2(0) = +1

D5’ = D5 + 2C56 - 2C53 = -2 + 2(1) - 2(0) = +0

• New gain with D2 D2’, D5 D5’

g25 = D2 + D5 - 2C52 = +1 + 0 - 2(0) = +1 (a3, b3) = (2, 5) [©Kang]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ch-9communities-220816124612-4745b556/85/Communities-in-Network-Science-44-320.jpg)