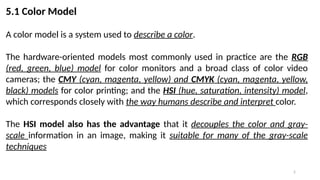

This lecture introduces the fundamentals of color representation and processing in the digital domain. It covers color models (RGB, CMY, HSV, HSI), color transformations, enhancement techniques, and color image segmentation. Applications in computer vision, multimedia, remote sensing, and medical imaging are highlighted to show the importance of color in image analysis.

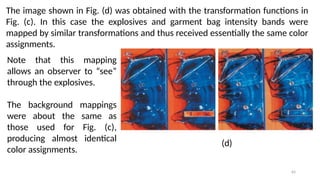

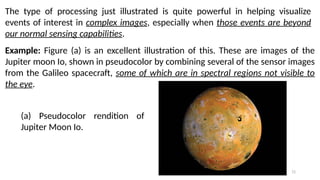

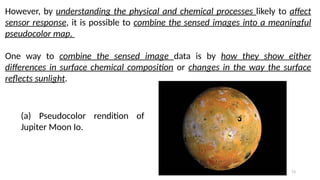

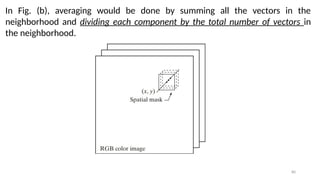

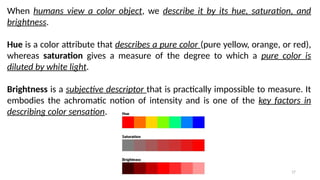

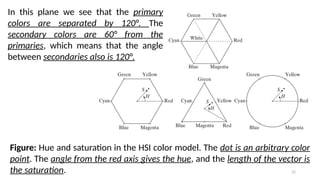

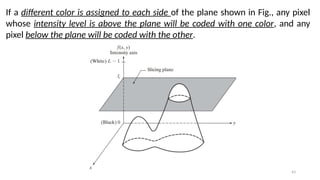

![5

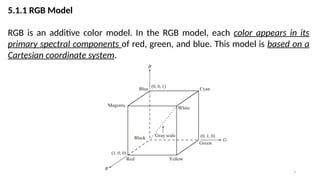

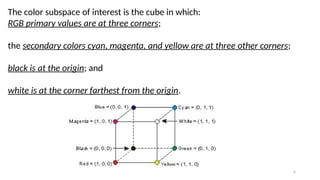

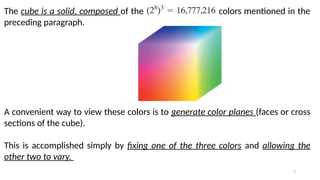

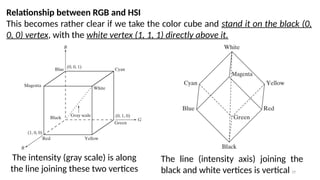

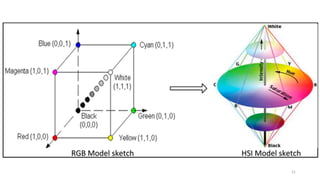

In this model, the gray scale (points of equal RGB values) extends from black to

white along the line joining these two points. For convenience, the assumption

is that all color values have been normalized so that the cube is the unit cube.

That is, all values of R, G, and B are assumed to be in the range [0, 1].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digitalimageprocessinglecture5-250817160959-0e227b3d/85/Color-Image-Processing-Digital-Image-Processing-Lecture-5-5-320.jpg)

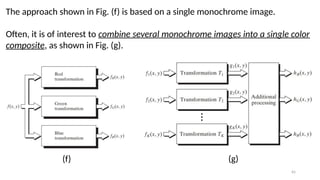

![6

The number of bits used to represent each pixel in RGB space is called the pixel

depth.

Consider an RGB image in which each of the red, green, and blue images is an 8-

bit image. Under these conditions each RGB color pixel [that is, a triplet of

values (R, G, B)] is said to have a depth of 24 bits (3 image planes times the

number of bits per plane).

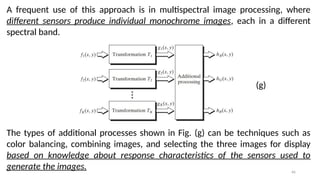

The term full-color image is used often to

denote a 24-bit RGB color image.

The total number of colors in a 24-bit

RGB image is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digitalimageprocessinglecture5-250817160959-0e227b3d/85/Color-Image-Processing-Digital-Image-Processing-Lecture-5-6-320.jpg)

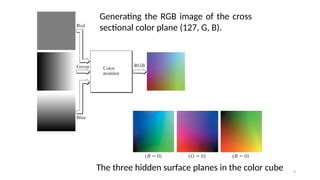

![8

For instance, a cross-sectional plane through the center of the cube and parallel

to the GB-plane is the plane (127, G, B) for

Here we used the actual pixel values rather than the mathematically convenient

normalized values in the range [0, 1] because the former values are the ones

actually used in a computer to generate colors.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digitalimageprocessinglecture5-250817160959-0e227b3d/85/Color-Image-Processing-Digital-Image-Processing-Lecture-5-8-320.jpg)

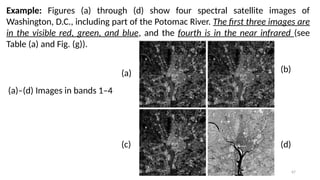

![13

Most devices that deposit colored pigments on paper, such as color printers and

copiers, require CMY data input or perform an RGB to CMY conversion

internally.

Cyan = White – Red

Magenta = White – Green

Yellow = White – Blue

This conversion is performed using the simple operation

Where, again, the assumption is that all color values have been normalized to

the range [0, 1].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digitalimageprocessinglecture5-250817160959-0e227b3d/85/Color-Image-Processing-Digital-Image-Processing-Lecture-5-13-320.jpg)

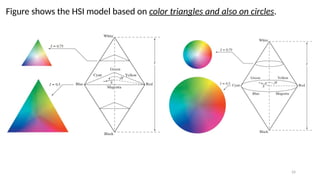

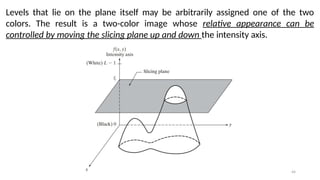

![20

Thus, if we wanted to determine the intensity component of any color point in

Fig, we would simply pass a plane perpendicular to the intensity axis and

containing the color point. The intersection of the plane with the intensity axis

would give us a point with intensity value in the range [0, 1].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digitalimageprocessinglecture5-250817160959-0e227b3d/85/Color-Image-Processing-Digital-Image-Processing-Lecture-5-20-320.jpg)

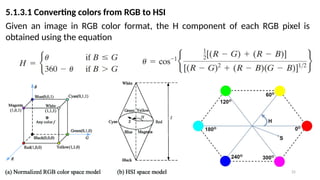

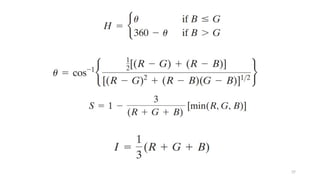

![26

The saturation component is given by

Finally, the intensity component is given by

It is assumed that the RGB values have been normalized to the range [0, 1] and

that angle is measured with respect to the red axis of the HSI space.

Hue can be normalized to the range [0, 1] by dividing by 360° all values

resulting from Eq.

The other two HSI components already are in this range if the given RGB

values are in the interval [0, 1].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digitalimageprocessinglecture5-250817160959-0e227b3d/85/Color-Image-Processing-Digital-Image-Processing-Lecture-5-26-320.jpg)

![27

Steps of Conversion

Normalize the RGB Values:

First, convert the RGB values to the [0, 1] range by dividing each component by

255. For example, consider a pixel with RGB values (100, 150, 200):](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digitalimageprocessinglecture5-250817160959-0e227b3d/85/Color-Image-Processing-Digital-Image-Processing-Lecture-5-27-320.jpg)

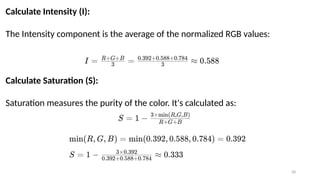

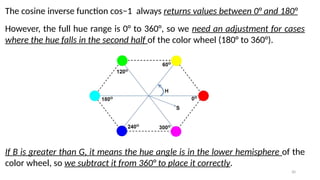

![29

Calculate Hue (H):

Hue represents the color type and is calculated using:

Finally, normalize to the [0, 1] range by dividing by 360°.

𝐻](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digitalimageprocessinglecture5-250817160959-0e227b3d/85/Color-Image-Processing-Digital-Image-Processing-Lecture-5-29-320.jpg)

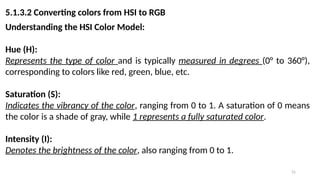

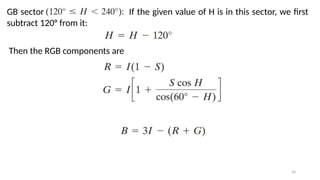

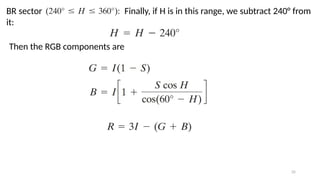

![32

5.1.3.2 Converting colors from HSI to RGB

Given values of HSI in the interval [0, 1], we now want to find the corresponding

RGB values in the same range.

The applicable equations depend on the

values of H.

There are three sectors of interest,

corresponding to the 120° intervals in the

separation of primaries.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digitalimageprocessinglecture5-250817160959-0e227b3d/85/Color-Image-Processing-Digital-Image-Processing-Lecture-5-32-320.jpg)

![33

We begin by multiplying H by 360°, which returns the hue to its original range

of [0°, 360°].

RG sector : When H is in this sector, the RGB components are given

by the equations](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digitalimageprocessinglecture5-250817160959-0e227b3d/85/Color-Image-Processing-Digital-Image-Processing-Lecture-5-33-320.jpg)

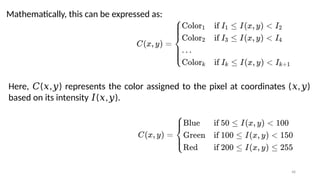

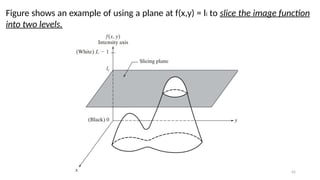

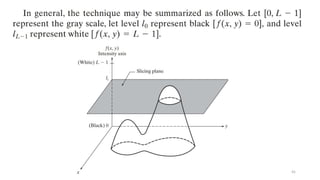

![47

Let ( , ) represent the intensity function of the image, where and are

𝐼 𝑥 𝑦 𝑥 𝑦

spatial coordinates, and ( , ) is the intensity at that point.

𝐼 𝑥 𝑦

Define Intensity Range:

Define a set of intensity intervals [𝐼1,𝐼2],[𝐼3,𝐼4],…,[𝐼𝑘,𝐼 +1

𝑘 ], where each interval

corresponds to a different color range.

Assign Color:

For each pixel with intensity value ( , ), assign a color based on which interval

𝐼 𝑥 𝑦

the intensity value falls into.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digitalimageprocessinglecture5-250817160959-0e227b3d/85/Color-Image-Processing-Digital-Image-Processing-Lecture-5-47-320.jpg)