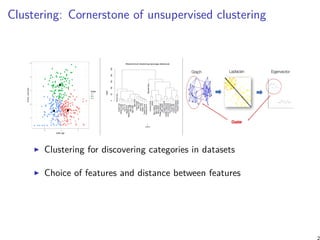

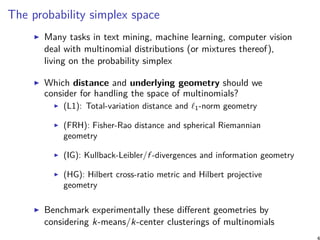

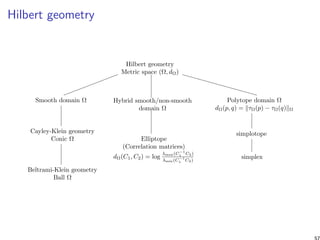

- The document discusses different geometric approaches for clustering multinomial distributions, including total variation distance, Fisher-Rao distance, Kullback-Leibler divergence, and Hilbert cross-ratio metric.

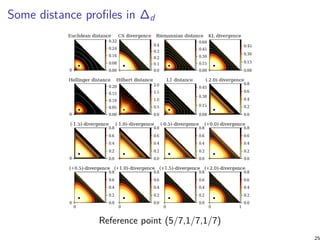

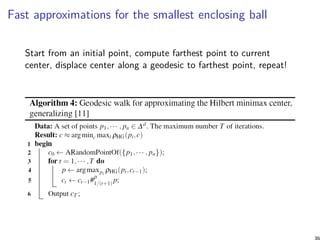

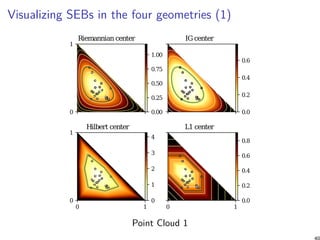

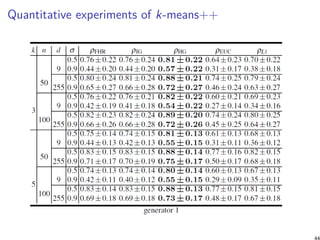

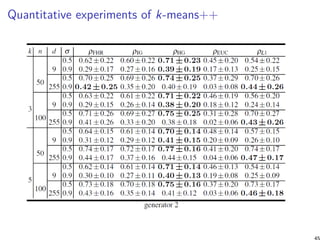

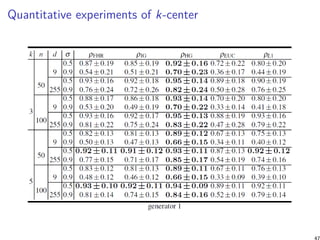

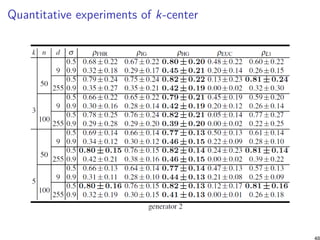

- It benchmarks k-means clustering using these four geometries on the probability simplex, finding that Hilbert geometry clustering yields good performance with theoretical guarantees.

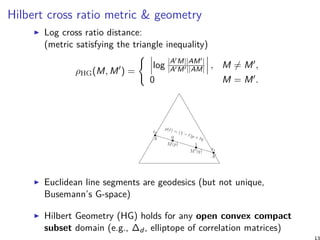

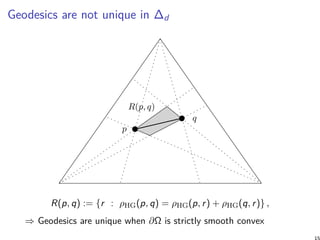

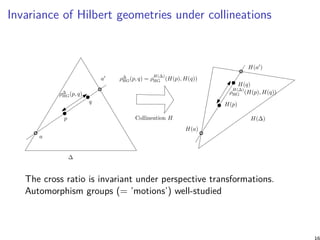

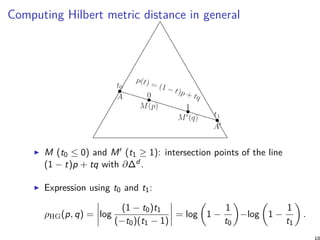

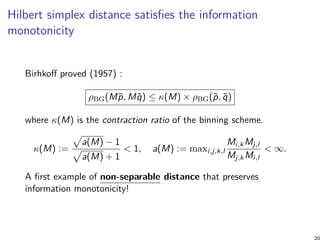

- The Hilbert cross-ratio metric defines a non-Riemannian Hilbert geometry on the simplex with polytopal balls, and satisfies information monotonicity properties desirable for clustering distributions.

![Motivations

Which geometry and distance are appropriate for a space of

probability distributions? for a space of correlation matrices?

Information geometry [5] focuses on the differential-geometric

structures associated to spaces of parametric distributions...

Benchmark different geometric space modelings

3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-clusteringhilbertgeometryml-181212073307/85/Clustering-in-Hilbert-geometry-for-machine-learning-3-320.jpg)

![The shape of ℓ1-balls in ∆d

For trinomials in ∆2 (with λ2 = 1 − (λ0 + λ1)), the ρL1

distance is given by:

ρL1(p, q) = |λ0

p − λ0

q| + |λ1

p − λ1

q| + |λ0

q − λ0

p + λ1

q − λ1

p|.

ℓ1-distance is polytopal: cross-polytope

Z = conv(±ei : i ∈ [d]) also called co-cube (orthoplex)

Shape of ℓ1-balls:

BallL1 (p, r) = (λp ⊕ rZ) ∩ H∆d

In 2D, regular octahedron cut by H∆2 = hexagonal shapes.

9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-clusteringhilbertgeometryml-181212073307/85/Clustering-in-Hilbert-geometry-for-machine-learning-9-320.jpg)

![Visualizing the 1D/2D/3D shapes of L1 balls in ∆d

Illustration courtesy of ’Geometry of Quantum States’, [1]

10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-clusteringhilbertgeometryml-181212073307/85/Clustering-in-Hilbert-geometry-for-machine-learning-10-320.jpg)

![Fisher-Hotelling-Rao Riemannian geometry (1930)

Fisher metric tensor [gij] (constant positive curvature):

gij(p) =

δij

λi

p

+

1

λ0

p

.

Statistical invariance yields unique Fisher metric [2]

Distance is a geodesic length (Levi-Civita connection ∇LC

with metric-compatible parallel transport)

Rao metric distance between two multinomials on Riemannian

manifold (∆d , g):

ρFHR(p, q) = 2 arccos

( d∑

i=0

√

λi

pλi

q

)

.

Can be embedded in the positive orthant of an Euclidean

d-sphere of Rd+1 by using the square root representation

λ →

√

λ = (

√

λ0, . . . ,

√

λd )

11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-clusteringhilbertgeometryml-181212073307/85/Clustering-in-Hilbert-geometry-for-machine-learning-11-320.jpg)

![Euclidean shape of balls in Hilbert projective geometry

Hilbert balls in ∆d : hexagons shapes (2D) [10], rhombic

dodecahedra (3D), polytopes [4] with d(d + 1) facets in

dimension d.

1.5

3.0

4.5

6.0

Not Riemannian/differential-geometric geometry because

infinitesimally small balls have not ellipsoidal shapes. (Tissot

indicatrix in Riemannian geometry)

A video explaining the shapes of Hilbert balls:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XE5x5rAK8Hk&t=1s

14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-clusteringhilbertgeometryml-181212073307/85/Clustering-in-Hilbert-geometry-for-machine-learning-14-320.jpg)

![Hilbert geometry generalizes Cayley-Klein hyperbolic

geometry

Defined for a quadric domain

(curved elliptical/hyperbolic Mahalanobis distances [6])

Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YHJLq3-RL58

17](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-clusteringhilbertgeometryml-181212073307/85/Clustering-in-Hilbert-geometry-for-machine-learning-17-320.jpg)

![Relationship with Birkhoff projective geometry

Instead of considering the (d − 1)-dimensional simplex ∆d ,

consider the the pointed cone Rd

+,∗.

Birkhoff projective metric on positive histograms:

ρBG(˜p, ˜q) := log maxi,j∈[d]

˜pi ˜qj

˜pj ˜qi

is scale-invariant ρBG(α˜p, β˜q) = ρBG(˜p, ˜q), for any α, β > 0.

O

˜p

˜q

p

q

e1 = (1, 0)

e2 = (0, 1)

∆1

R2

+,∗

ρHG(p, q)

ρBG(˜p, ˜q)

19](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-clusteringhilbertgeometryml-181212073307/85/Clustering-in-Hilbert-geometry-for-machine-learning-19-320.jpg)

![Shape of Hilbert balls in an open simplex

A ball in the Hilbert simplex geometry has a Euclidean

polytope shape with d(d + 1) facets [4]

In 2D, Hilbert balls have 2(2 + 1) = 6 hexagonal shapes

varying with center locations. In 3D, the shape of balls are

rhombic-dodecahedron

When the domain is not simplicial, Hilbert balls can have

varying complexities [10]

No metric tensor in Hilbert geometry because infinitesimally

the ball shapes are polytopes and not ellipsoids.

Hilbert geometry can be studied via Finsler geometry

21](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-clusteringhilbertgeometryml-181212073307/85/Clustering-in-Hilbert-geometry-for-machine-learning-21-320.jpg)

![k-means++ clustering (seeding initialization)

For an arbitrary distance D, define the k-means objective

function (NP-hard to minimize):

ED(Λ, C) =

1

n

n∑

i=1

minj∈{1,...,k}D(pi : cj)

k-means++: Pick uniformly at random at first seed c1, and

then iteratively choose the (k − 1) remaining seeds according

to the following probability distribution:

Pr(cj = pi ) =

D(pi , {c1, . . . , cj−1})

∑n

i=1 D(pi , {c1, . . . , cj−1})

(2 ≤ j ≤ k).

A randomized seeding initialization of k-means, can be further

locally optimized using Lloyd’s batch iterative updates, or

Hartigan’s single-point swap heuristic [9], etc.

28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-clusteringhilbertgeometryml-181212073307/85/Clustering-in-Hilbert-geometry-for-machine-learning-28-320.jpg)

![Performance analysis of k-means++ [8]

Let κ1 and κ2 be two constants such that κ1 defines the

quasi-triangular inequality property:

D(x : z) ≤ κ1 (D(x : y) + D(y : z)) , ∀x, y, z ∈ ∆d

,

and κ2 handles the symmetry inequality:

D(x : y) ≤ κ2D(y : x), ∀x, y ∈ ∆d

.

Theorem

The generalized k-means++ seeding guarantees with high

probability a configuration C of cluster centers such that:

ED(Λ, C) ≤ 2κ2

1(1 + κ2)(2 + log k)E∗

D(Λ, k)

29](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-clusteringhilbertgeometryml-181212073307/85/Clustering-in-Hilbert-geometry-for-machine-learning-29-320.jpg)

![Performance analysis of k-means++

In any normed space (X, ∥ · ∥), the k-means++ with

D(x, y) = ∥x − y∥2 is 16(2 + log k)-competitive.

In any inner product space (X, ⟨·, ·⟩), the k-means++ with

D(x, y) = ⟨x − y, x − y⟩ is 16(2 + log k)-competitive.

Hilbert simplex geometry is isometric to a normed vector

space [4] (Theorem 3.3):

(∆d

, ρHG) ≃ (V d

, ∥ · ∥NH)

Theorem

k-means++ seeding in a Hilbert simplex geometry in fixed

dimension is 16(2 + log k)-competitive.

31](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-clusteringhilbertgeometryml-181212073307/85/Clustering-in-Hilbert-geometry-for-machine-learning-31-320.jpg)

![k-Center clustering: farthest first traversal heuristic

Guaranteed approximation factor of 2 in any metric space [3]

34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-clusteringhilbertgeometryml-181212073307/85/Clustering-in-Hilbert-geometry-for-machine-learning-34-320.jpg)

![Smallest Enclosing Ball (SEB)

Given a finite point set {p1, . . . , pn} ∈ ∆d , the SEB in Hilbert

simplex geometry is centered at

c∗

= arg min

c∈∆d

maxi∈{1,...,n}ρHG(c, xi ),

with radius

r∗

= minc∈∆d maxi∈{1,...,n}ρHG(c, xi ).

Decision problem can be solved by Linear Programming (LP),

and optimization as a LP-type problem [7]

Do not scale well in high dimensions

35](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-clusteringhilbertgeometryml-181212073307/85/Clustering-in-Hilbert-geometry-for-machine-learning-35-320.jpg)

![Summary and conclusion [11]

Introduced Hilbert/Birkhoff geometry for the probability

simplex (= space of categorical distributions) and the

elliptope (= space of correlation matrices). But also

simplotope (product of simplices), etc.

Hilbert simplex geometry is isometric to a normed vector

space (hilds for any Hilbert polytopal geometry)

Non-separable distance that satisfies the information

monotonicity (contraction ratio of linear operator)

Novel closed form Hilbert/Birkhoff distance formula for the

correlation (metric) and covariance matrices (projective

metric)

Benchmark experimentally four types of geometry for k-means

and k-center clusterings

Hilbert/Birkhoff geometry experimentally well-suited for

58](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-clusteringhilbertgeometryml-181212073307/85/Clustering-in-Hilbert-geometry-for-machine-learning-58-320.jpg)

![References I

Ingemar Bengtsson and Karol Życzkowski.

Geometry of quantum states: an introduction to quantum entanglement.

Cambridge university press, 2017.

L. L. Campbell.

An extended čencov characterization of the information metric.

American Mathematical Society, 98(1):135–141, 1986.

Teofilo F Gonzalez.

Clustering to minimize the maximum intercluster distance.

Theoretical Computer Science, 38:293–306, 1985.

Bas Lemmens and Roger Nussbaum.

Birkhoff’s version of Hilbert’s metric and its applications in analysis.

Handbook of Hilbert Geometry, pages 275–303, 2014.

Frank Nielsen.

An elementary introduction to information geometry.

ArXiv e-prints, August 2018.

Frank Nielsen, Boris Muzellec, and Richard Nock.

Classification with mixtures of curved Mahalanobis metrics.

In IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), pages 241–245, 2016.

Frank Nielsen and Richard Nock.

On the smallest enclosing information disk.

Information Processing Letters, 105(3):93–97, 2008.

Frank Nielsen and Richard Nock.

Total Jensen divergences: Definition, properties and k-means++ clustering, 2013.

arXiv:1309.7109 [cs.IT].

59](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slides-clusteringhilbertgeometryml-181212073307/85/Clustering-in-Hilbert-geometry-for-machine-learning-59-320.jpg)