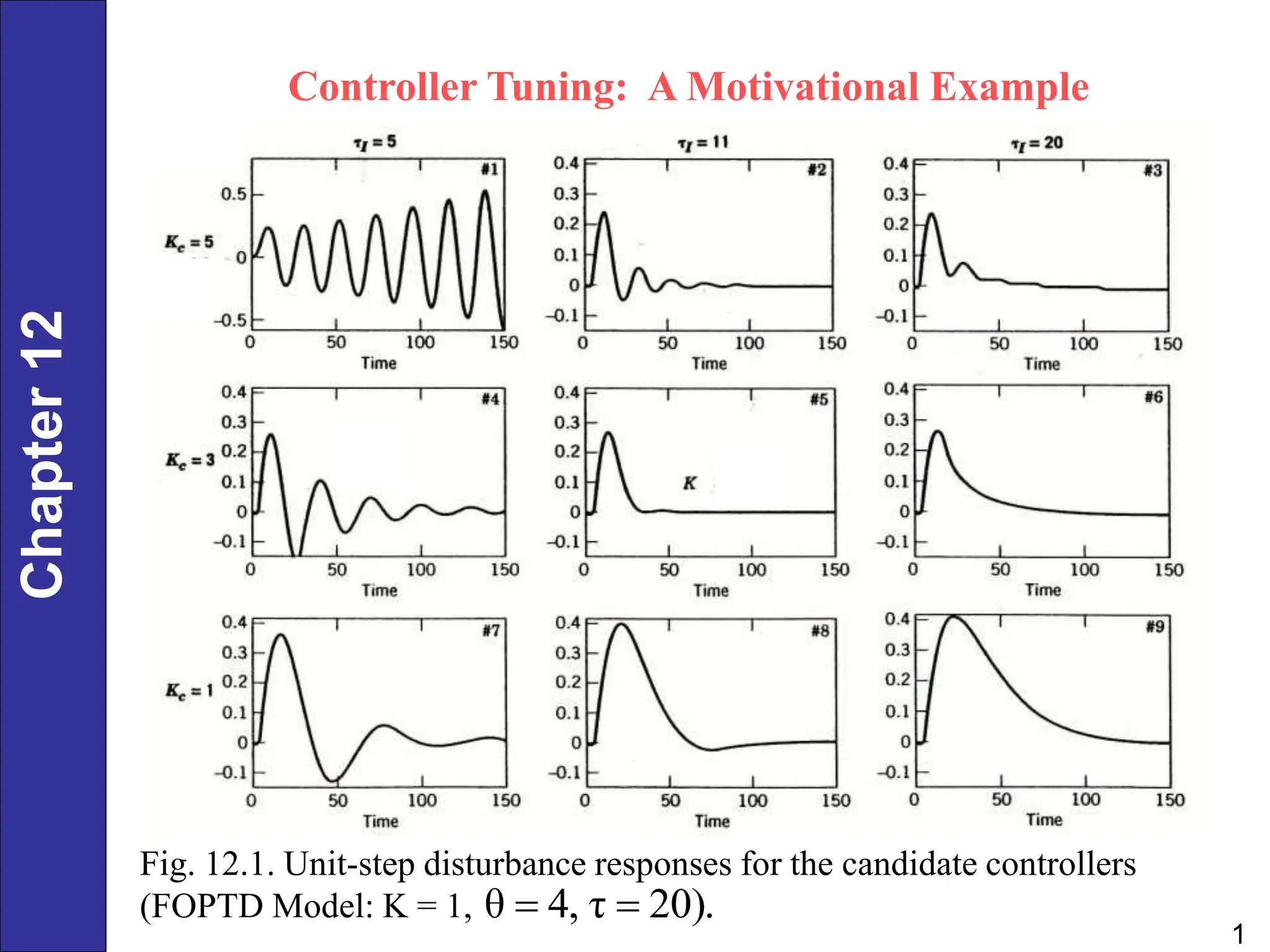

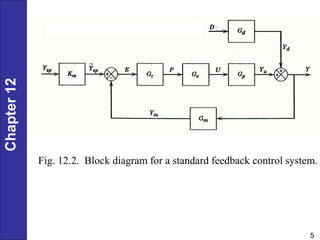

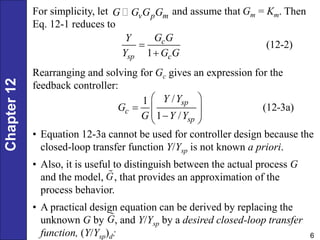

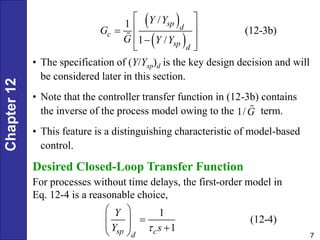

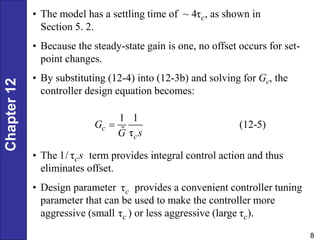

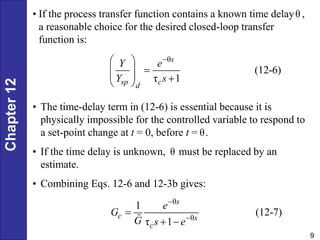

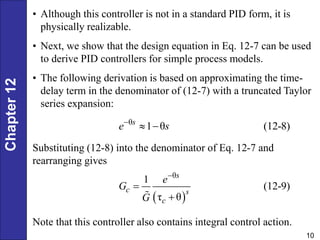

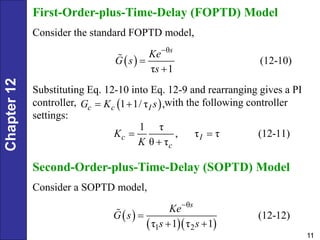

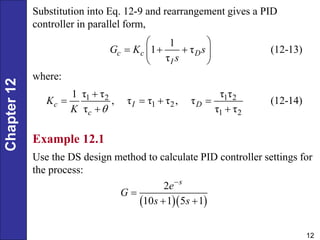

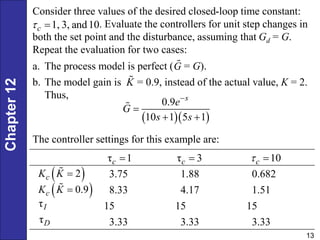

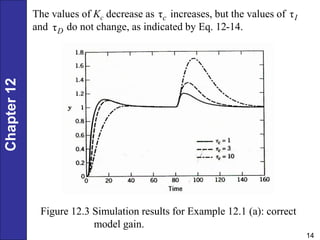

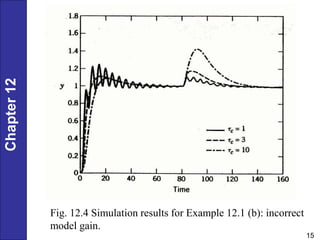

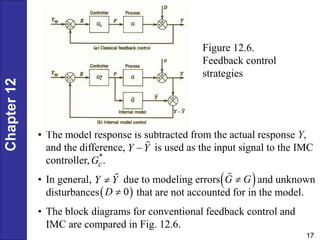

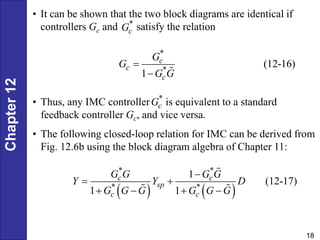

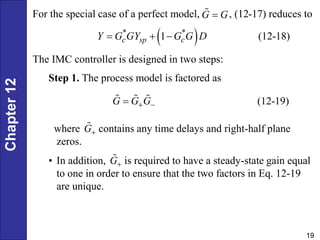

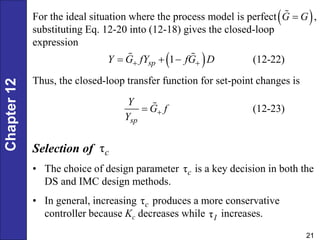

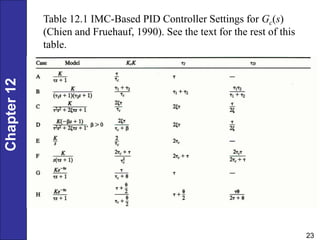

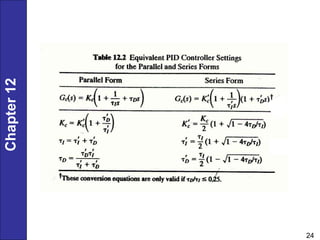

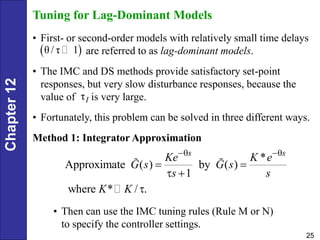

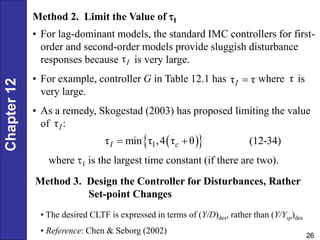

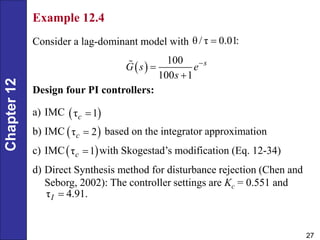

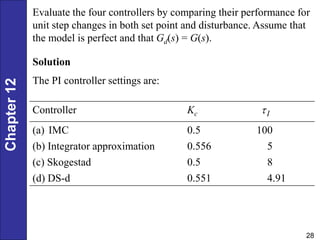

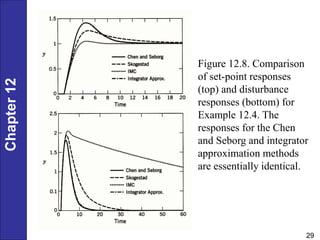

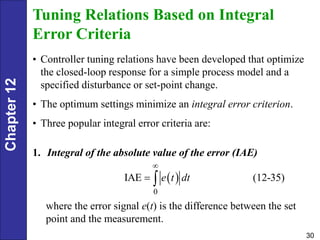

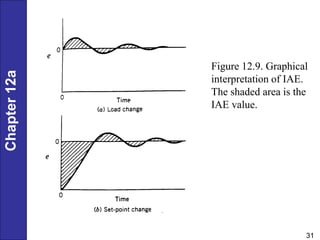

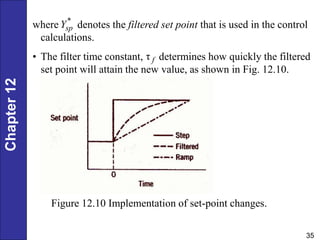

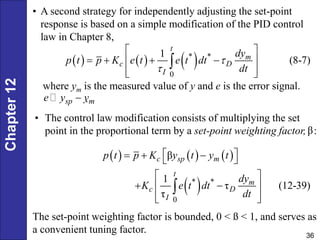

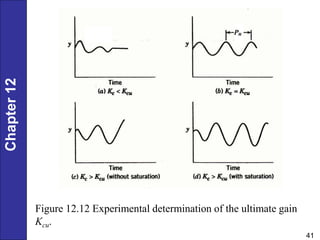

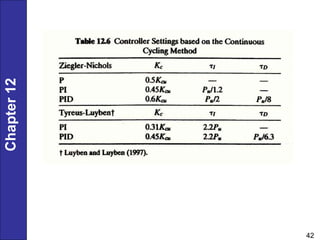

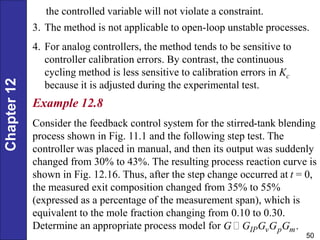

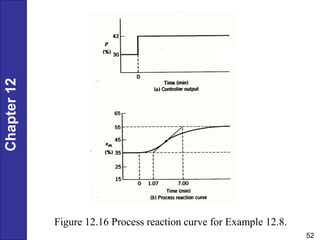

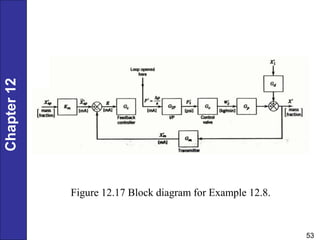

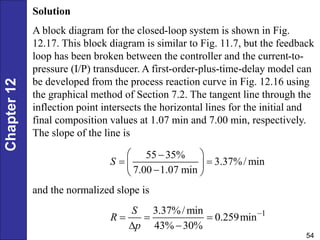

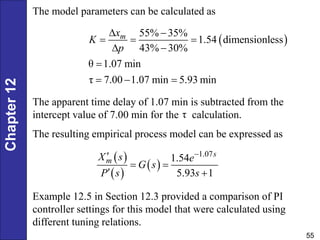

Chapter 12 discusses PID controller design, tuning, and performance criteria for closed-loop systems, emphasizing stability, disturbance rejection, and set-point tracking. It presents several tuning techniques, including direct synthesis and internal model control, detailing how to derive controller settings from process models. Additionally, the chapter illustrates the design of controllers for first-order and second-order systems, highlighting practical examples and modifications for lag-dominant models.