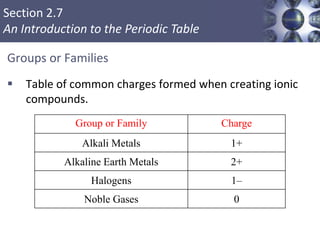

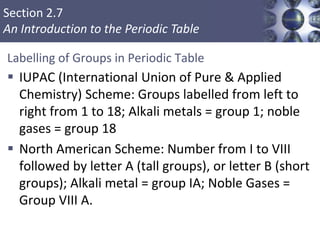

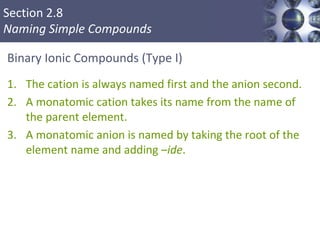

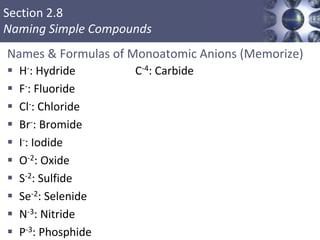

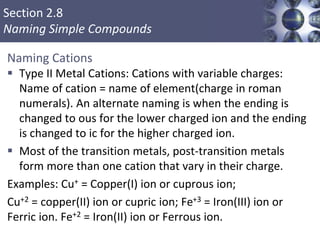

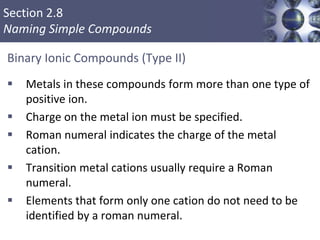

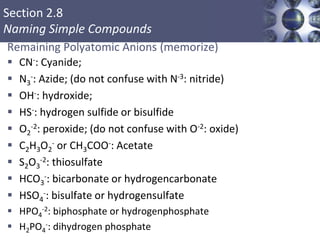

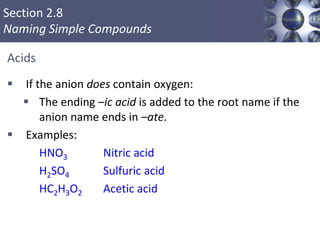

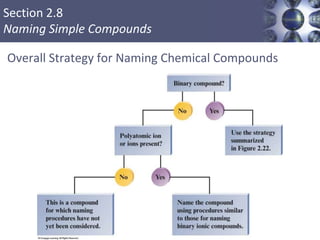

The document outlines key concepts in atomic structure and early models of the atom. It discusses early Greek and alchemist views, fundamental chemical laws proposed by scientists like Lavoisier, Proust, and Dalton. Dalton proposed his atomic theory stating atoms are indestructible spheres that combine to form compounds. The document then outlines experiments by Thomson, Millikan, Rutherford and others that led to the modern view of the atom consisting of a tiny, dense nucleus surrounded by electrons. It introduces concepts of isotopes, ions, molecules, and bonding. The periodic table is presented along with common naming conventions for ionic compounds.