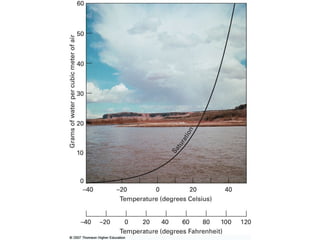

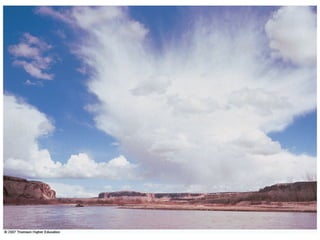

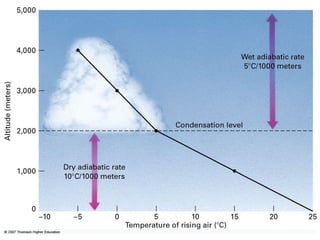

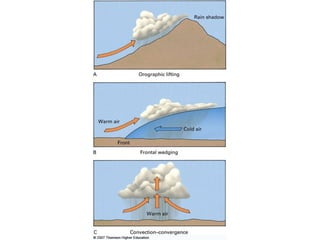

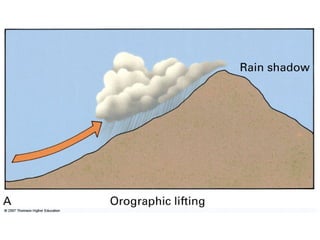

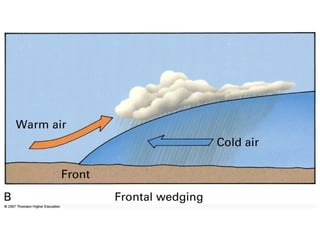

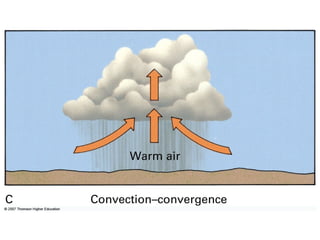

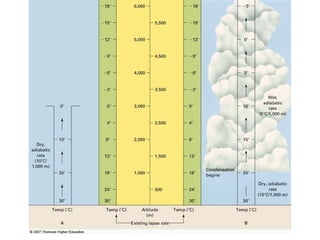

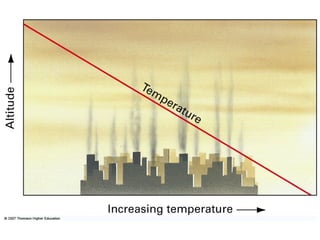

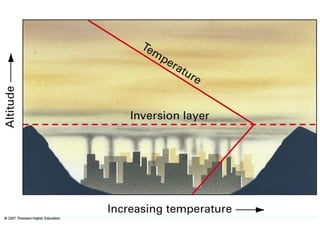

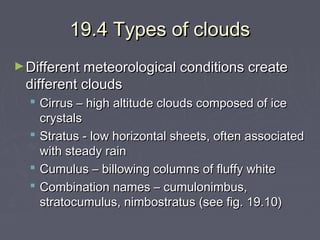

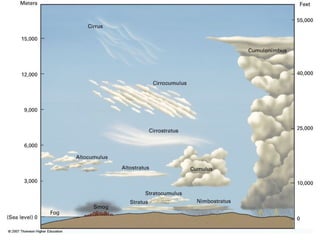

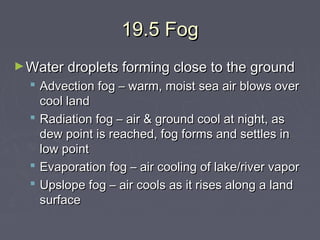

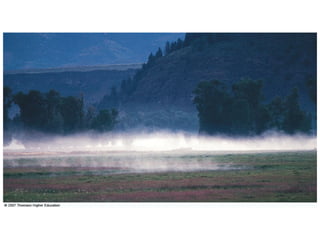

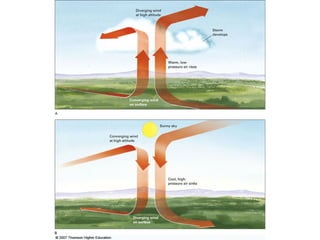

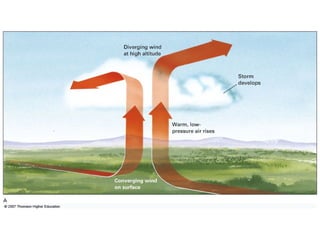

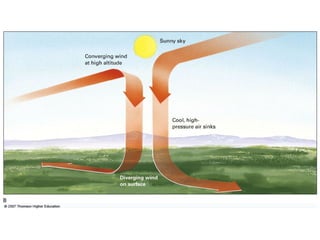

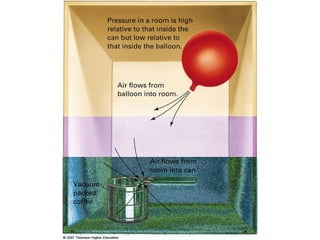

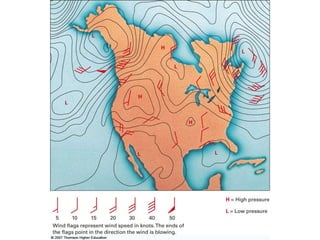

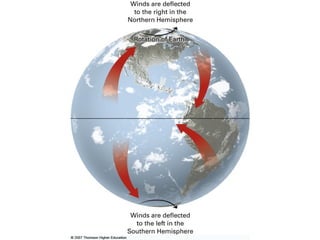

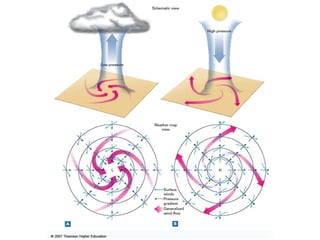

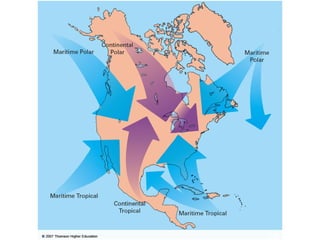

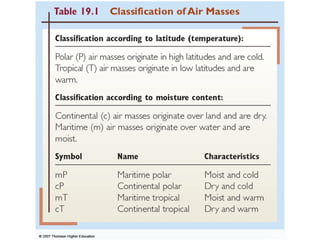

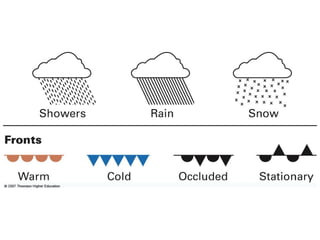

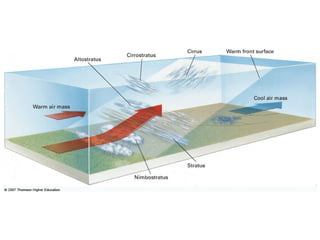

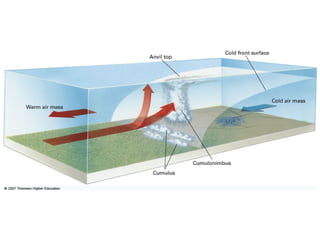

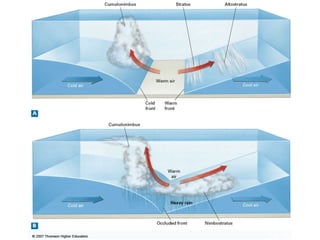

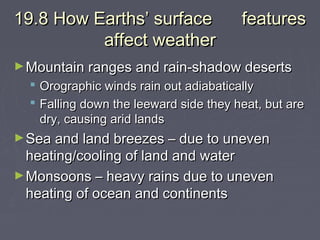

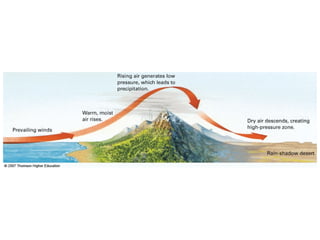

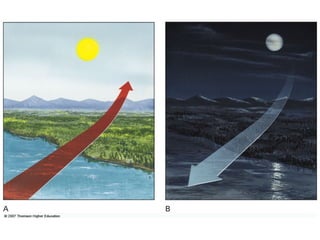

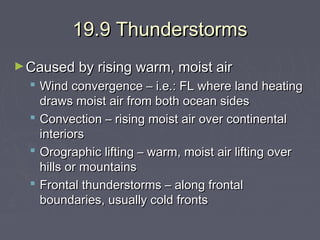

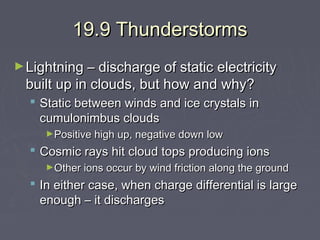

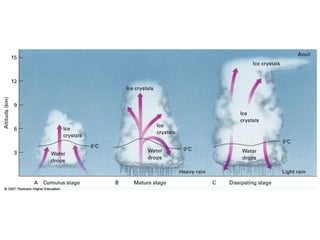

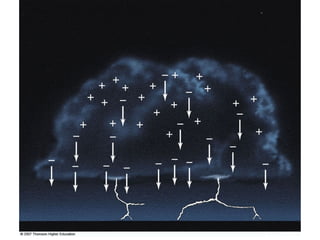

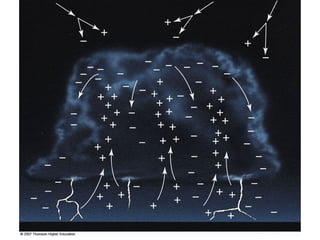

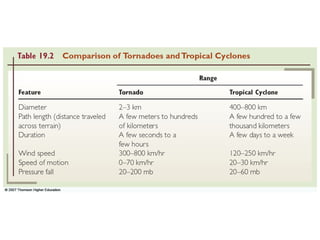

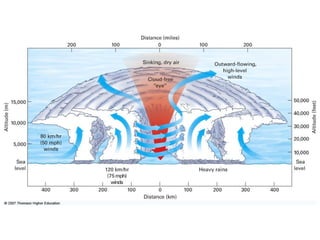

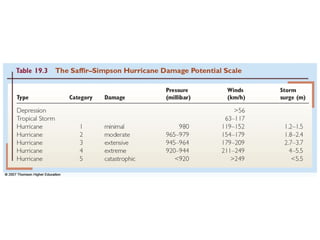

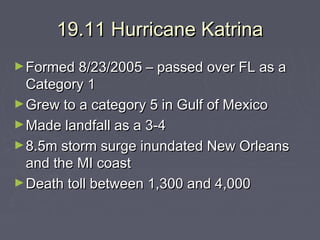

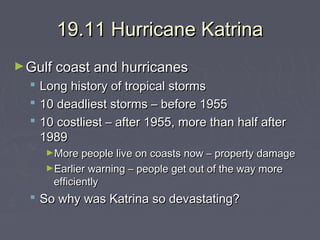

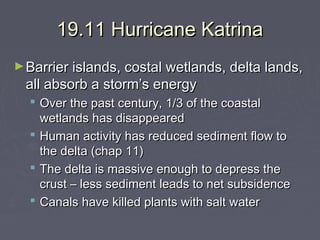

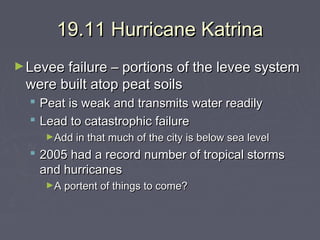

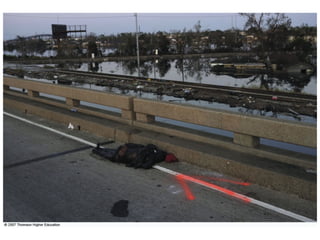

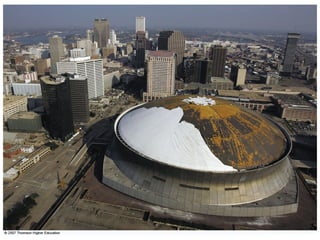

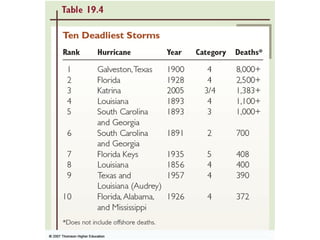

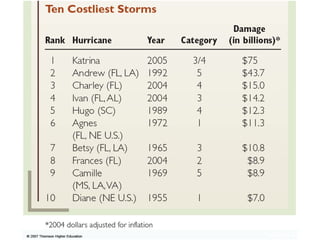

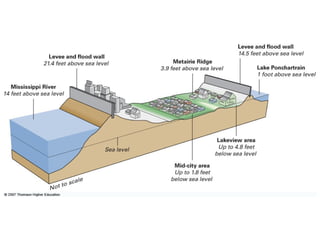

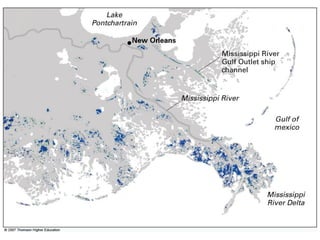

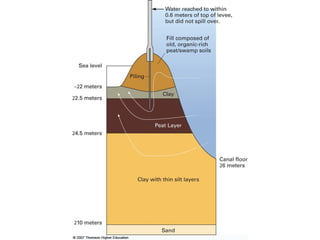

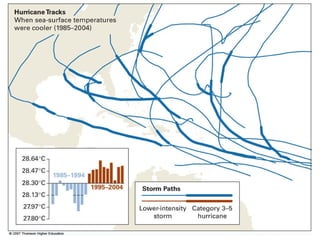

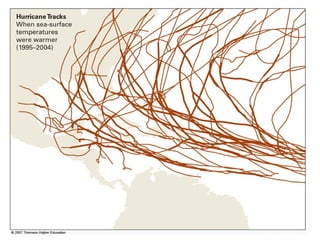

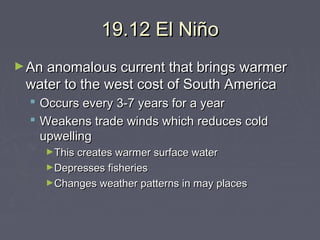

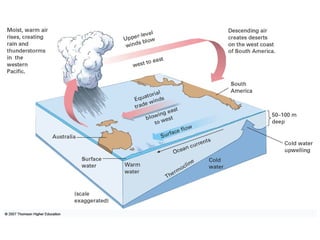

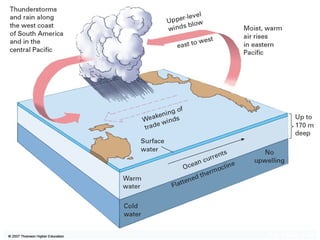

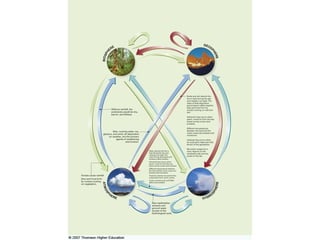

This chapter discusses the processes of moisture, clouds, and weather. It begins by explaining humidity and how moisture condenses in the air. It then discusses how air rises and cools, leading to cloud formation and different types of precipitation. The chapter outlines various cloud types and how weather phenomena like fog, wind, and atmospheric pressure develop. It concludes by examining large storm systems such as hurricanes, tornadoes, and El Niño events, providing examples of specific storms like Hurricane Katrina.