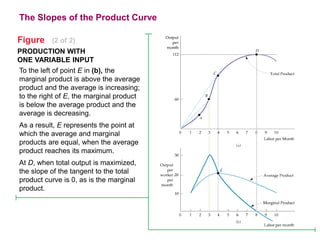

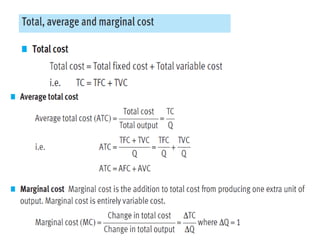

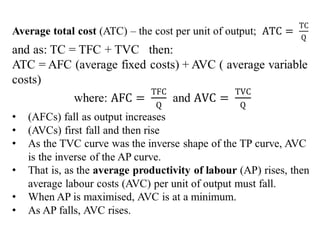

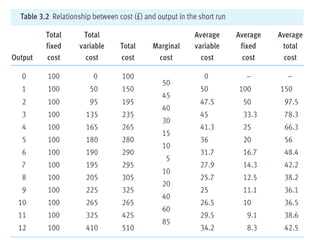

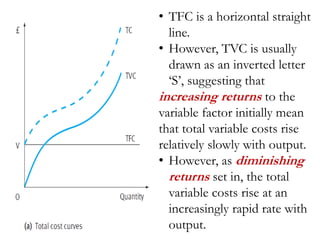

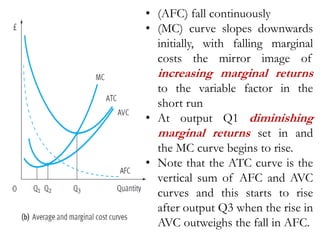

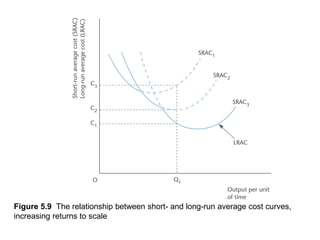

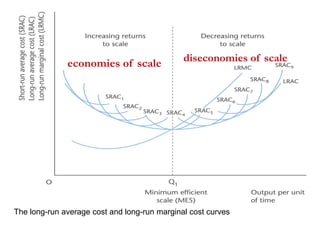

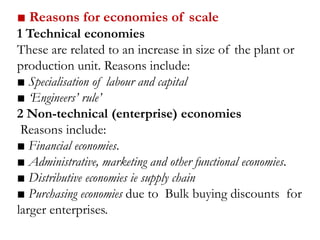

This document discusses production and costs in both the short-run and long-run. In the short-run, at least one factor of production is fixed, while in the long-run all factors are variable. The factors of production are land, labor, capital, and entrepreneurship. Laws of returns to scale describe how output responds to changing variable inputs. Short-run costs include total, fixed, and variable costs. Long-run average costs depend on whether there are increasing, constant, or decreasing returns to scale. Economies of scale from specialization, bulk purchasing, and other factors can lower long-run average costs.