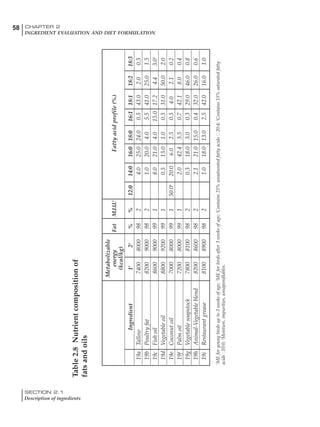

The document discusses the evaluation and testing of various feed ingredients. It describes 34 common feed ingredients like corn, wheat, soybean meal and by-products. It also discusses the various tests that can be performed on ingredients like proximate analysis, amino acid analysis and metabolizable energy tests. Finally, it covers various feed additives that may be included, such as anticoccidials, antibiotics, enzymes and pigments.