The document provides an overview and assessment of the implementation of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) Chapter of the 2nd Philippine Human Rights Action Plan from 2012-2016. It discusses the accomplishments of government agencies in enhancing the capacity of the justice system to implement laws protecting women's rights, promoting non-discrimination, and fulfilling women's rights through legal reforms. Key achievements include passage of new laws and policies, increased accountability mechanisms, and strategic plans to eliminate violence against women.

![4

e) The Domestic Workers Act of 2013 which includes protection of workers from VAW as well

trafficking.

11. The past three-years and a half saw the continued and enhanced efforts of the justice system1

to close the

gaps in the implementation of the 5 priority laws. There have been an increasing number of accountability

mechanisms, e.g. LCAT-VAWC, created at the local levels to implement the Strategic Plans on VAWC and

on Trafficking in Persons. All member agencies of the inter-agency mechanisms including the local

governments actively contributed to eliminate violence against women.

12. Below are the detailed discussions on the accomplishments of the concerned government agencies on

Thematic Objective 1 taking into account their contributions in fulfilling the strategic indicators.

2. Updates and Performances

On Legislative, administrative and judicial measures for improving the capacity of the justice system in

handling gender issues and concerns, 2012-2015

A. Legislative and Policy-Related Measures

13. Prior to 2012, several laws had been enacted that aimed to protect women from violence and abuse. Apart

from the five (5) anti-VAW priority legislations [Anti-Violence against Women and their Children Act of

2004 (RA 9262), Anti-Sexual Harassment Law of 1995 (RA 7877), Anti-Rape Law of 1997 (RA 8353),

Rape Victim Assistance and Protection Act of 1998 (RA 8505) and Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act of 2003

(RA 9208)], other laws with anti-VAW related provisions that were enacted as of 2012 include the Anti-

Child Pornography Act (RA 9775, 2009), Anti Photo and Video Voyeurism Act (RA 9995, 2009), Magna

Carta of Women (RA 9710, 2009), Anti-Torture Act (RA 9745, 2009), Philippine Disaster Risk Reduction

and Management (PDRRM) Act (RA 10121, 2010), Cybercrime Prevention Act (RA 10175, 2012) and

Responsible Parenthood and Reproductive Health Act (RA 10354, 2012). These laws are captured in the

Baseline Study on the Magna of Women (MCW) 2009 and Progress Report on the Implementation of the

MCW 2010-20122

prepared by the PCW. They are also mentioned in the various gender-related reports

submitted by the agency to the United Nations as those on the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms

of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) and the Beijing Platform for Action (BPfA).

14. The Anti-Child Pornography Act protects every child from all forms of exploitation and abuse including,

the use of a child in pornographic performances and materials and the inducement or coercion of a child to

engage or be involved in pornography through whatever means. The Cybercrime Prevention Act also

comes in support to Anti-Child Pornography Act where it responds to the rapidly changing times ushered in

by the developments in technology by regulating the widespread use of the internet in the commission of

certain crimes.

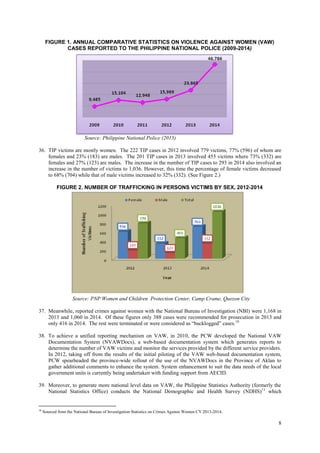

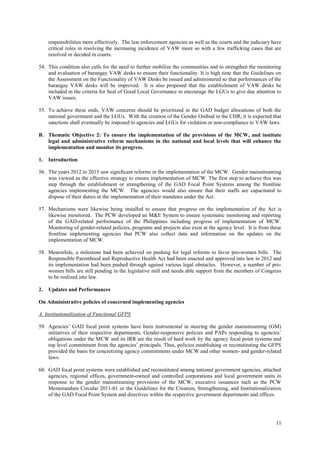

15. Sections 9 of the MCW provides for the protection of women from all forms of violence, while Section 10

seeks to protect women in times of disaster, calamities and other crisis situation. Section 4 of the Anti-

Torture Act includes “rape and sexual abuse, including the insertion of foreign objects into the sex organ or

rectum…” among the list of acts of torture. The PDRRM Act ensures that disaster risk reduction and

climate change measures are gender responsive.

16. An important milestone achieved in 2012 is the passage of RA 10354 or the Responsible Parenthood and

Reproductive Health Act which included a section on Care for Victim-Survivors of Gender-Based

Violence, Maternal and Newborn Health Care in Crisis Situations which should also respond to cases of

gender-based violence, and Gender-Sensitive Handling of Clients.

17. Among the VAW-related laws that were approved between the years 2013 to 2015 include: a) Domestic

Workers Act (RA 10361, 2013); b) the Expanded Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act (RA 10364, 2013); c) the

Act Declaring the November 25 of Every Year as the “National Consciousness Day For The Elimination Of

1

As defined in the PHRP II-CEDAW Chapter, the justice system, as referred to under Thematic Objective 1, is composed of the five pillars

of justice: (a) community – DSWD and DILG; (b) police – PNP and its affiliate agencies; (c) prosecution – DOJ; (d) courts/judiciary –

Supreme Court; and (e) penology – Bureau of Corrections, Bureau of Jail Management and other similar offices of government.

2

The Baseline Study on the Magna Carta of Women (2009) and the First-Term Progress Report on the Implementation of the MCW (2010-

2012) is on its finalization stage. It will be presented in a Multi-stakeholders’ Meeting the soonest the report is finalized.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cedaw-160215035652/85/CEDAW-Accomplishment-Report-4-320.jpg)