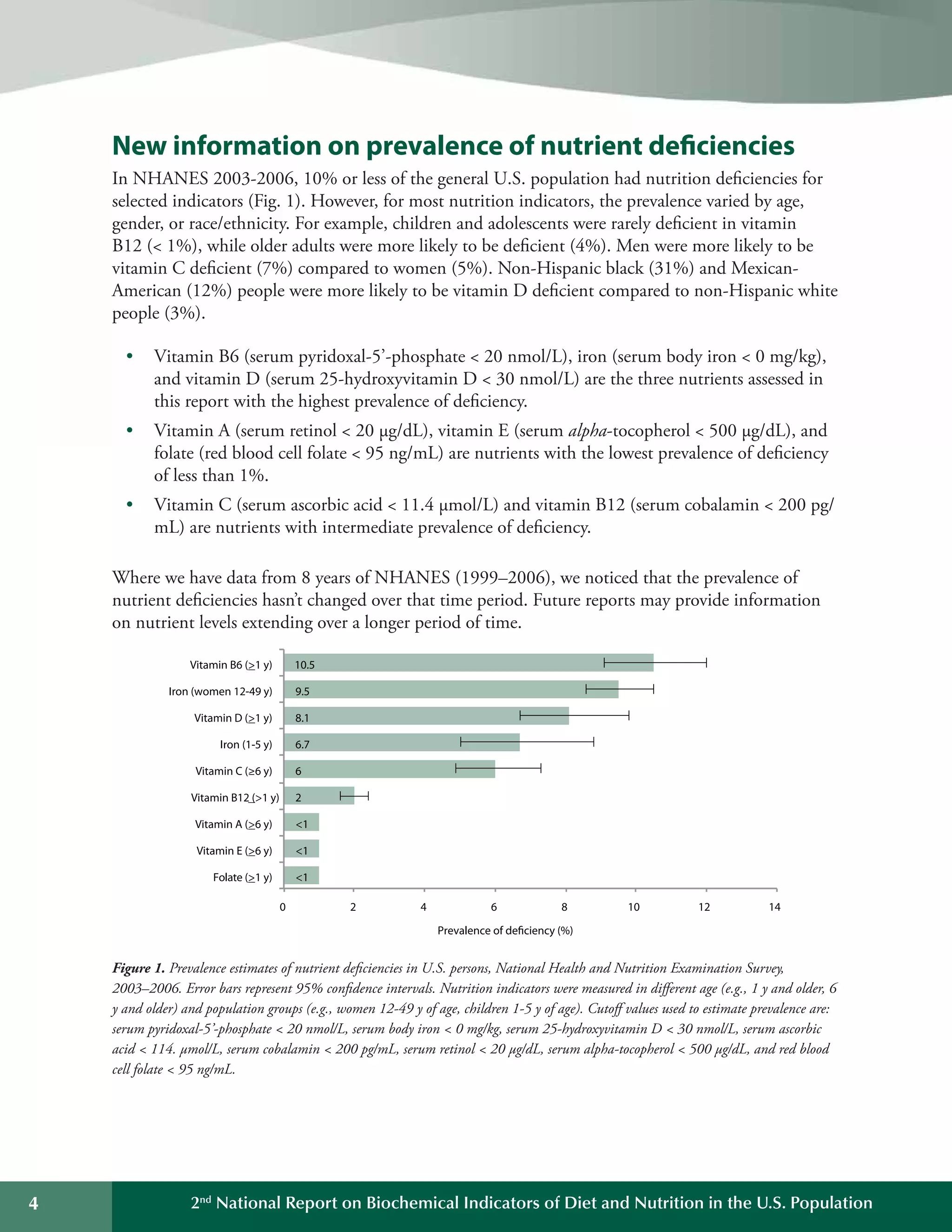

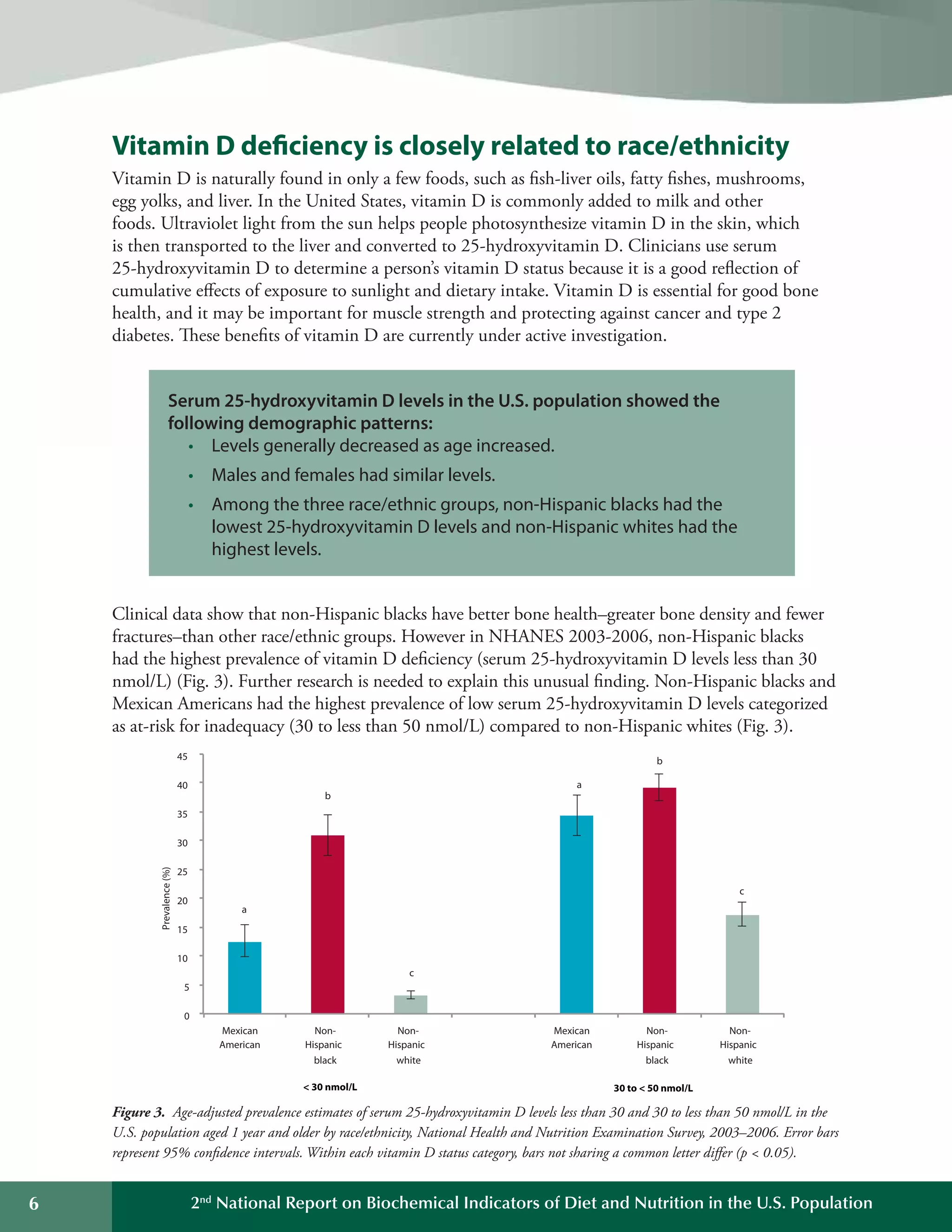

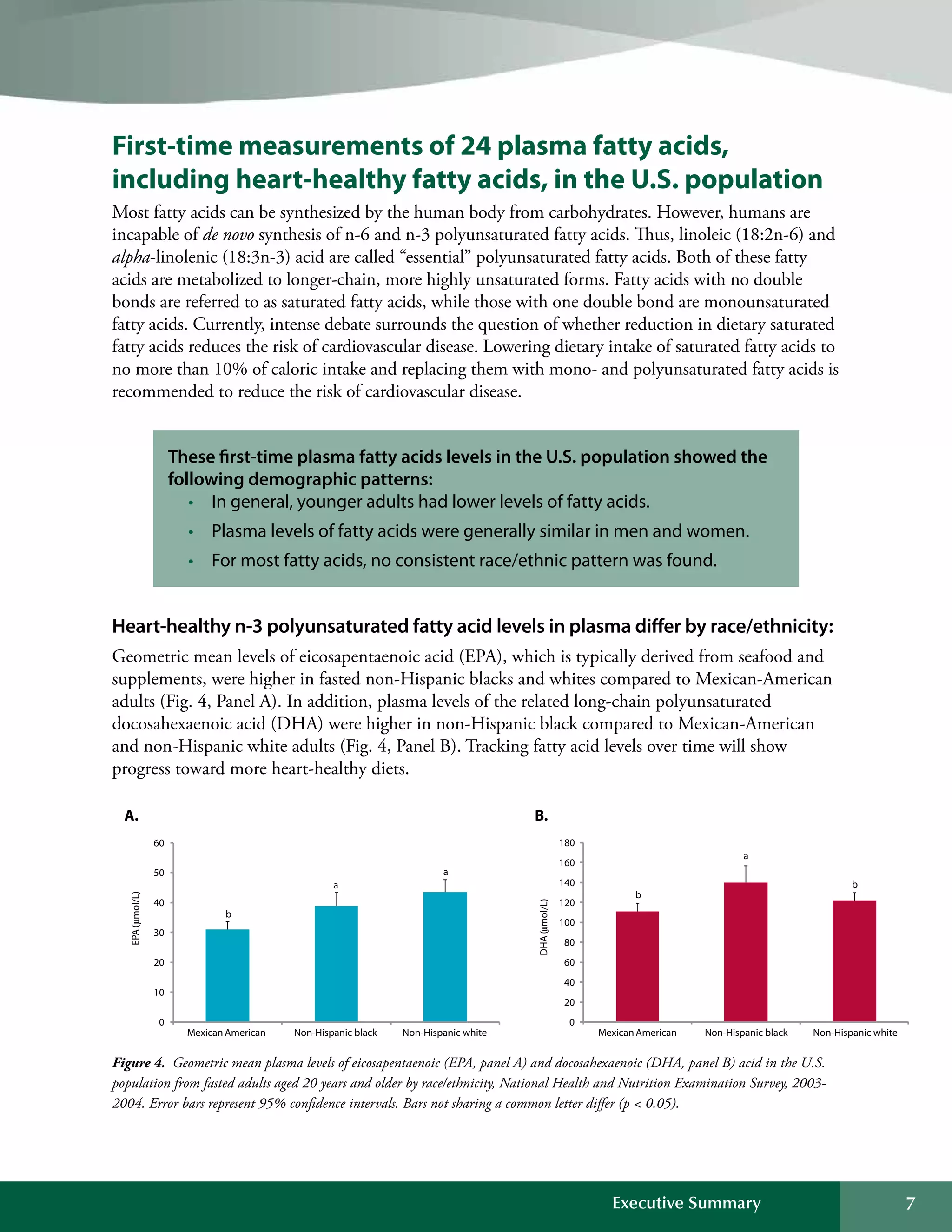

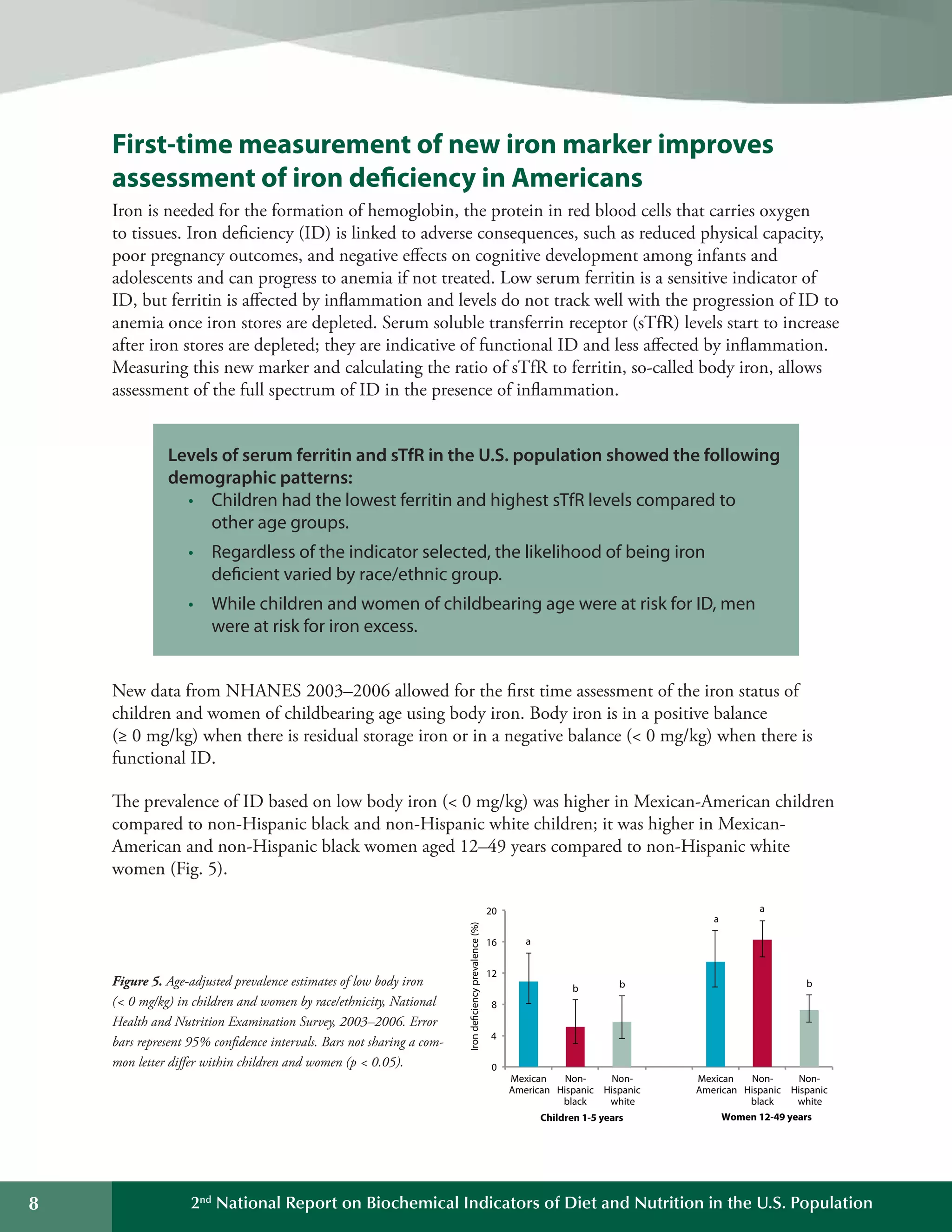

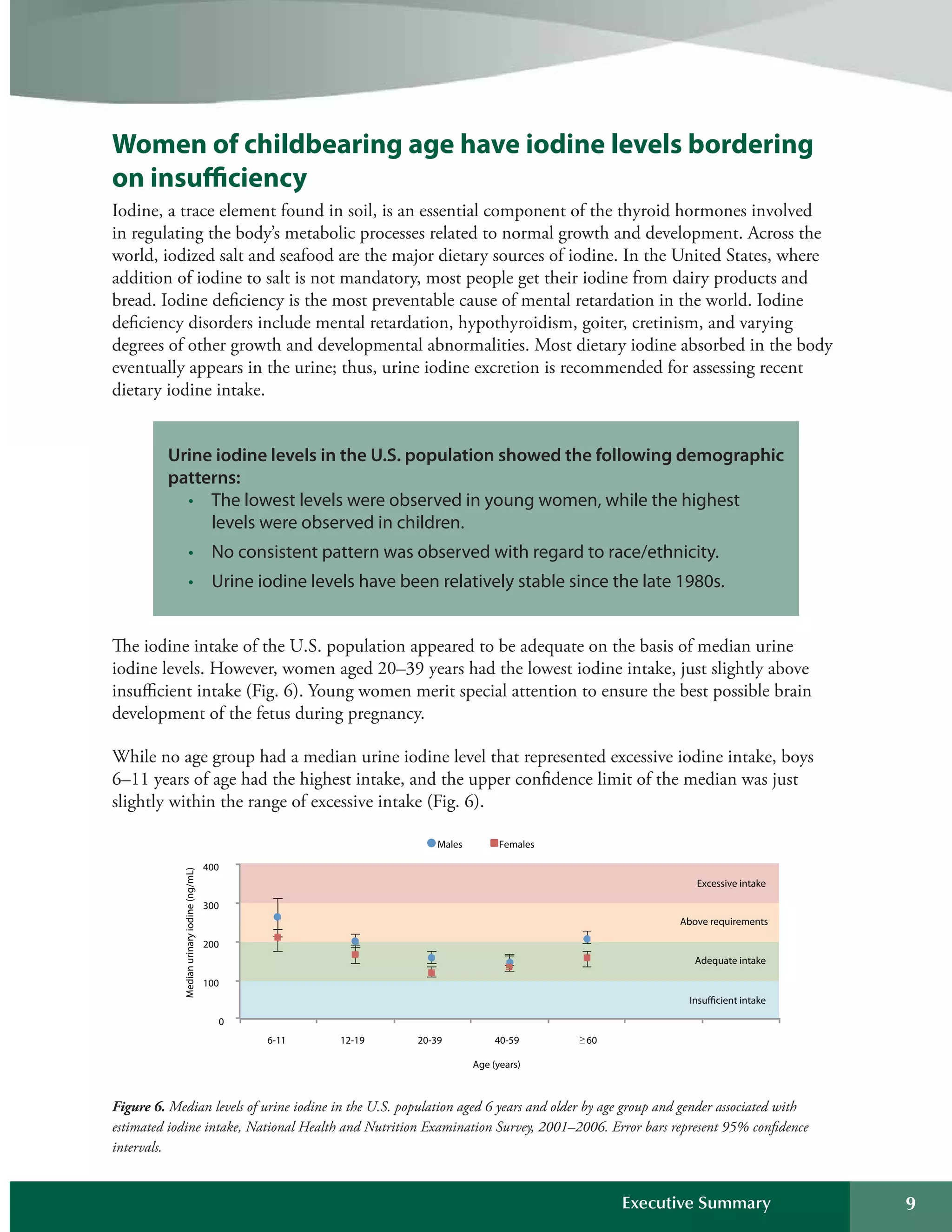

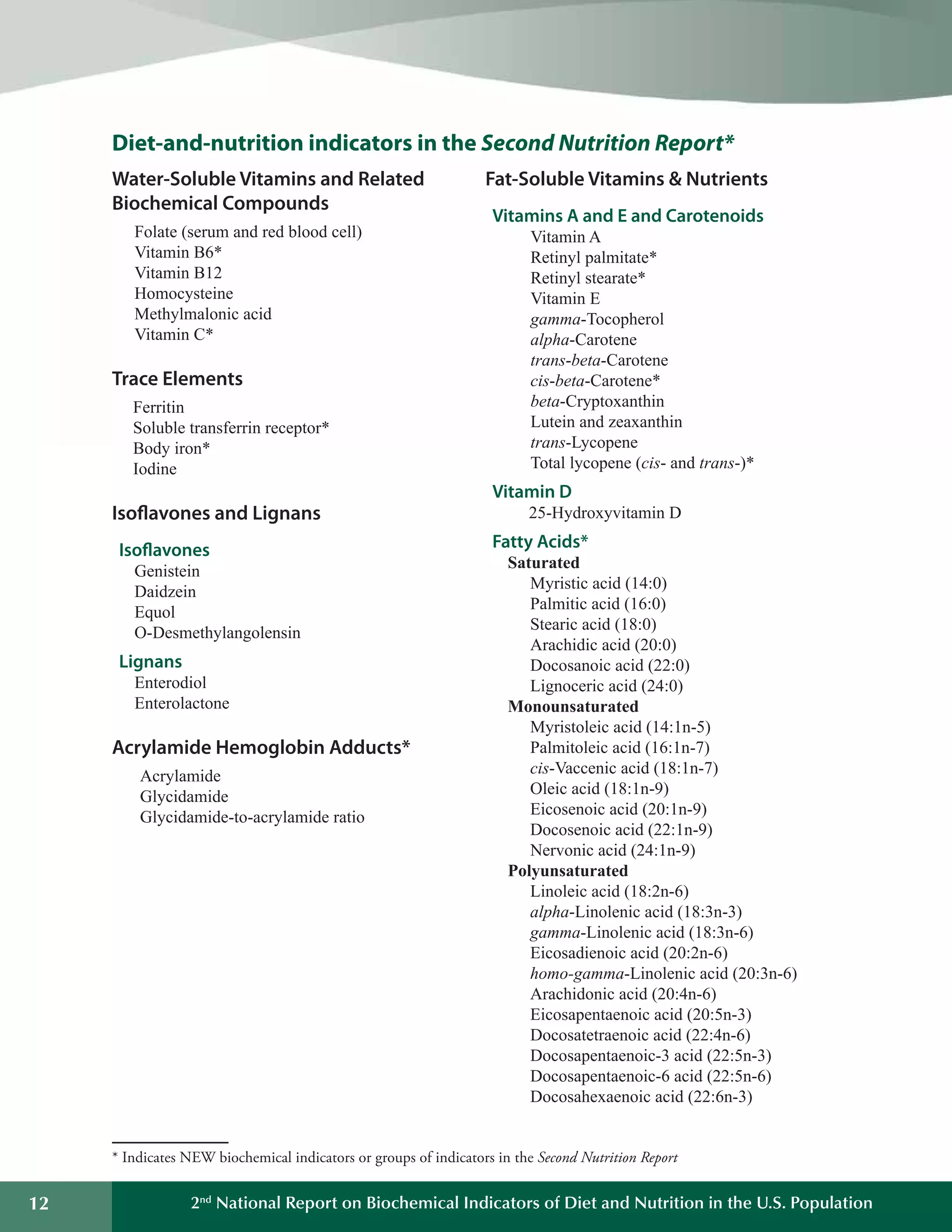

This document summarizes the key findings of the Second National Report on Biochemical Indicators of Diet and Nutrition in the U.S. Population from 2012. It analyzes biochemical indicators measured in U.S. residents from 2003-2006 to assess nutrient levels and deficiencies. The report finds the highest prevalence of deficiencies for vitamin B6, iron, and vitamin D. It also introduces new biochemical indicators and data features to track nutrition status over time. The goal is to inform public health efforts to improve the American population's diet and nutrition.