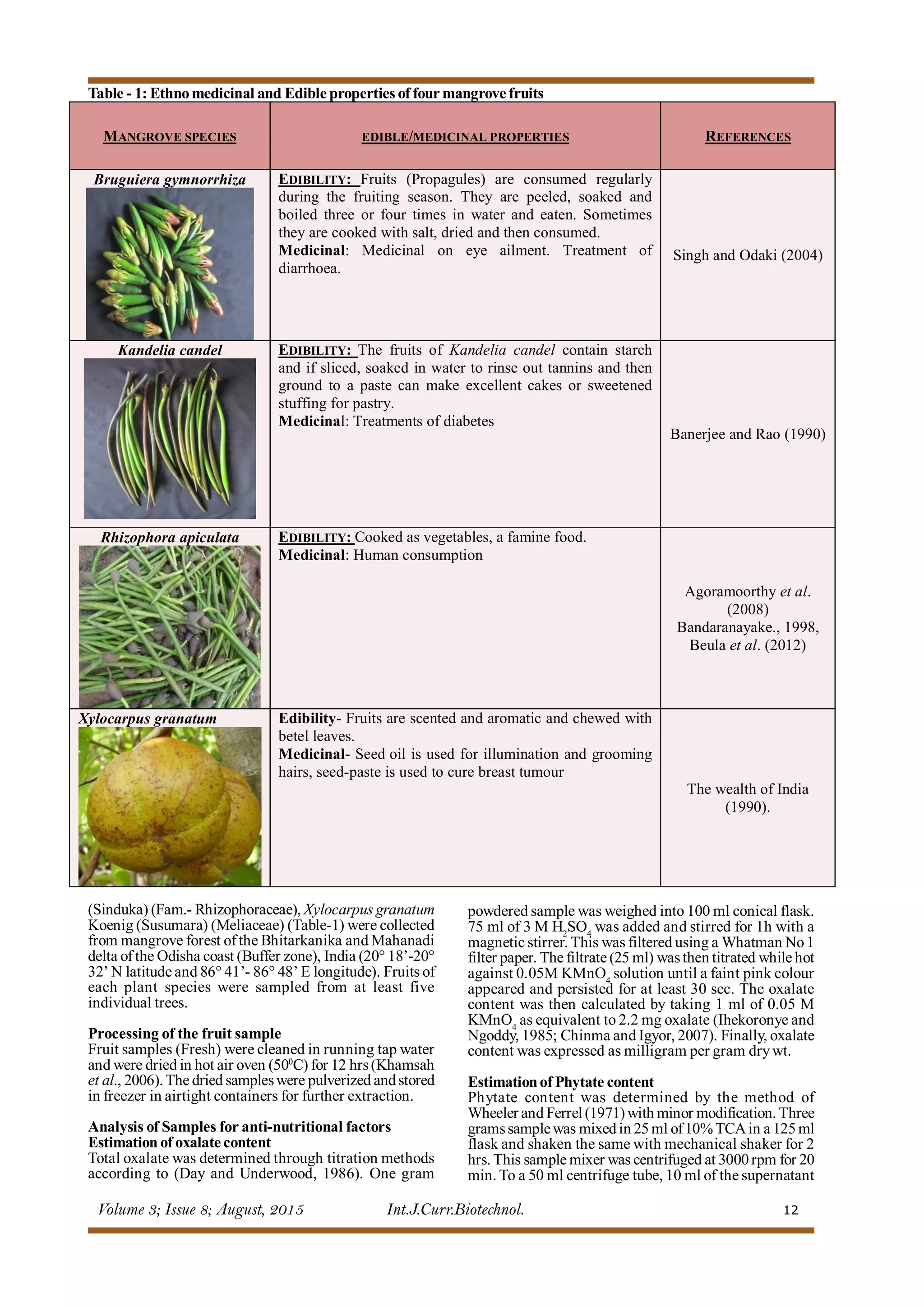

This document summarizes a study that analyzed the anti-nutritional properties of four edible mangrove fruits found in Odisha, India. The study found that the fruit of Xylocarpus granatum had the highest oxalate content, while Kandelia candel fruit had the highest phytate and saponin contents. X. granatum also had the highest tannin level. All four fruits contained measurable levels of anti-nutrients and consuming large amounts was not recommended. The findings provide information on the anti-nutritional properties of these edible mangrove fruits.