This document discusses the vulnerability of Africa to climate change and provides recommendations. Key points:

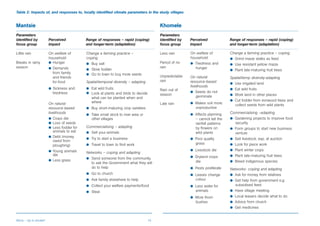

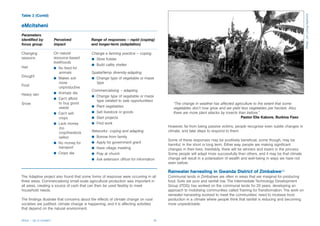

1) Africa is highly vulnerable to climate change due to widespread poverty and dependence on natural resources for livelihoods. Small-scale farming provides most food and employment but is reliant on rainfall.

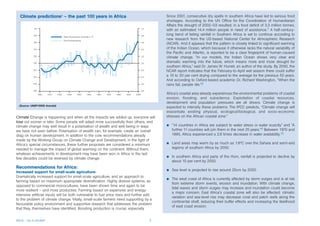

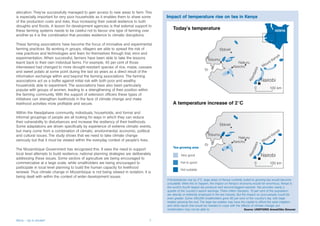

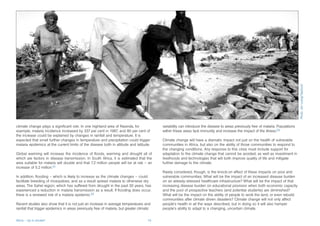

2) Climate change is already affecting Africa through increasing drought, worsening food shortages, coastal erosion, and rising sea levels. Projections include more drought in southern Africa and parts of the Horn of Africa by 2050.

3) Recommendations include dramatically increasing support for small-scale, diverse agriculture; rich countries cutting greenhouse gas emissions deeper than Kyoto targets; and ensuring initiatives are "climate-proof" and