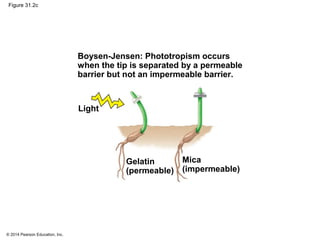

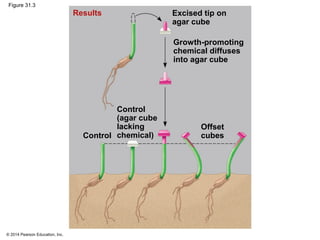

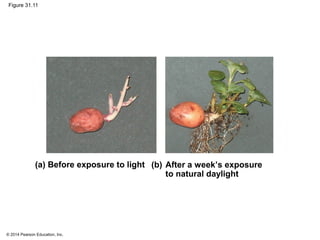

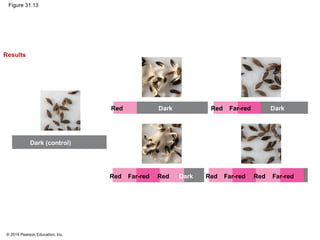

This document provides an overview of plant responses to internal and external signals. It discusses how plant hormones help coordinate growth, development, and responses to stimuli. The major classes of plant hormones are described, including auxin, cytokinins, gibberellins, brassinosteroids, abscisic acid, and ethylene. The roles of these hormones in processes like cell elongation, fruit growth, seed dormancy, and drought tolerance are summarized. The document also covers how plants respond to light via photoreceptors, and the importance of light signals for plant photomorphogenesis, phototropism, and other responses.