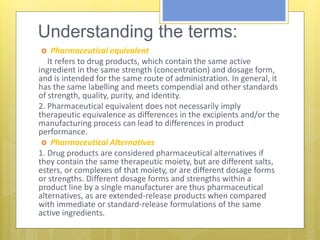

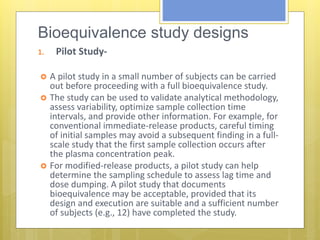

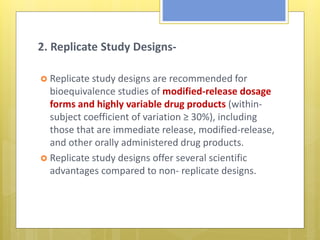

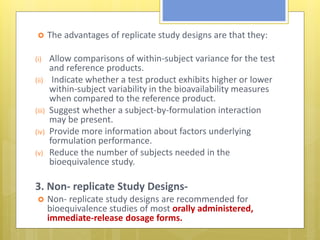

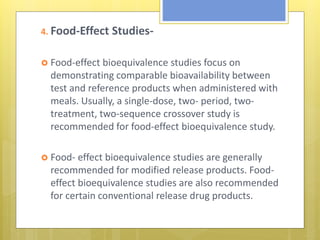

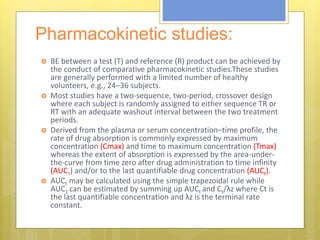

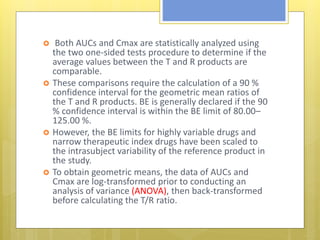

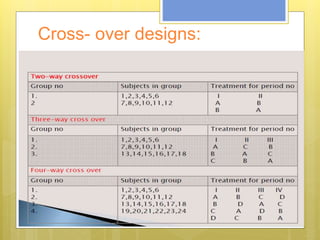

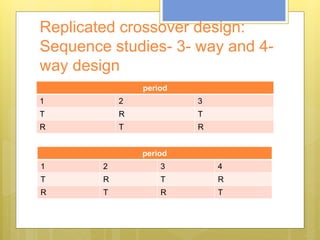

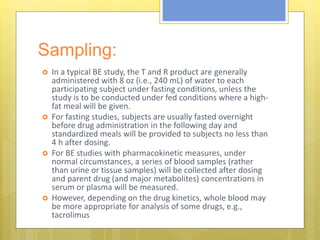

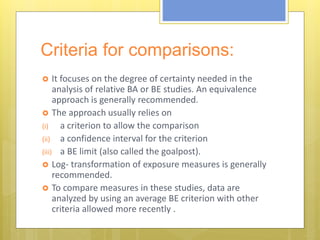

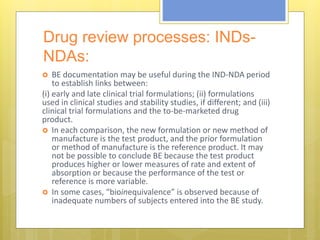

This document discusses the design and evaluation of bioequivalence studies. It defines bioequivalence as the absence of a significant difference in the rate and extent to which the active drug becomes available at the site of action when administered under similar conditions. The document discusses various study designs including crossover, replicate, and non-replicate designs. It also covers sampling, criteria for comparisons between test and reference products, and the roles of bioequivalence studies in drug review and approval processes.