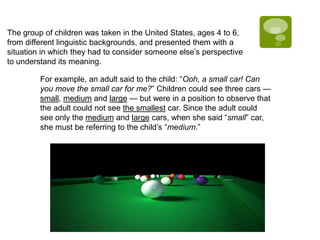

Two new studies show that exposure to multiple languages improves children's cognitive and social skills. A study of 4-6 year olds found that bilingual children were better able to take someone else's perspective to understand their meaning. For example, if an adult asked for the "small" car when only the medium and large cars were visible, bilingual children were more likely to understand the adult meant the medium car. A second study of 14-16 month old babies found that those exposed to multiple languages were more likely to hand an adult the object they could both see, rather than an identical object only the baby could see. These findings suggest that exposure to multiple languages, even without full bilingual ability, can facilitate interpersonal understanding