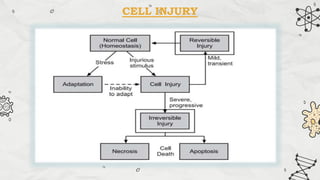

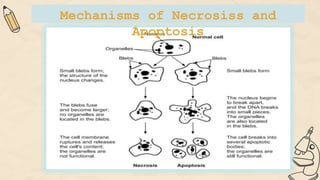

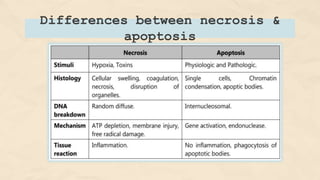

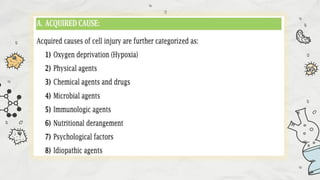

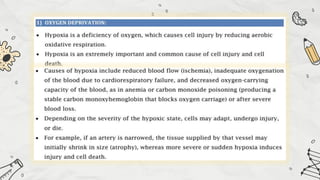

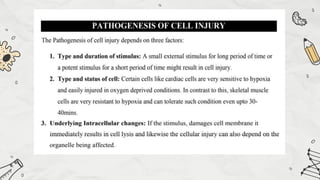

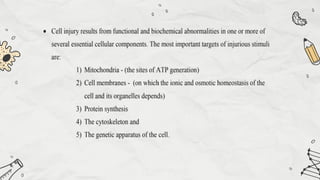

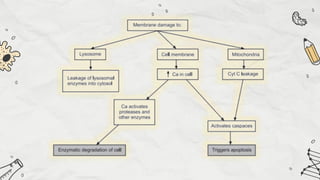

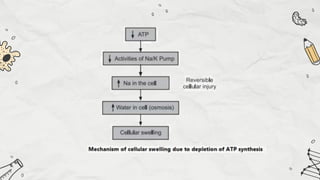

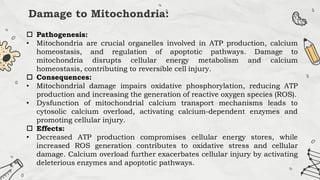

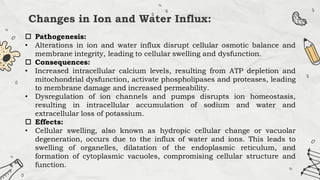

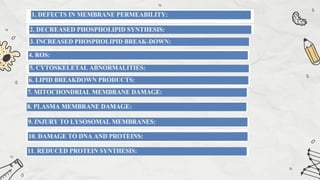

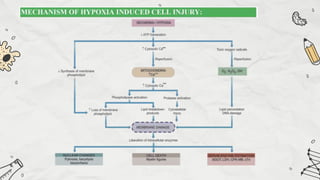

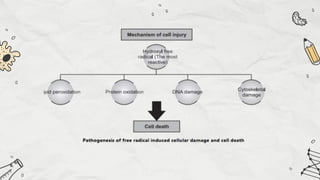

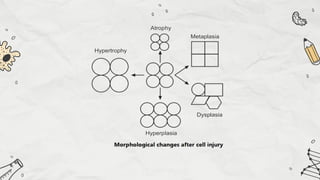

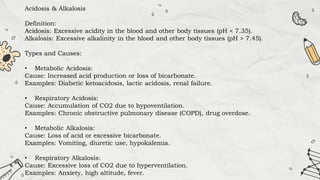

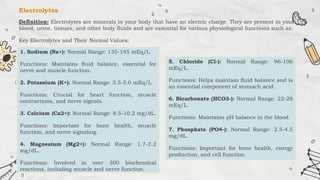

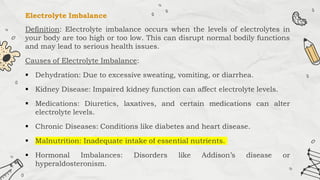

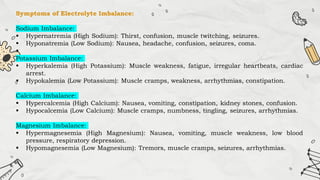

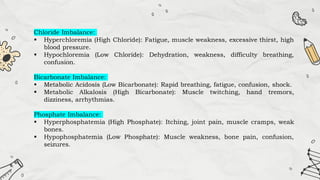

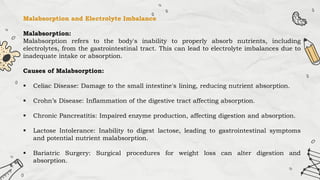

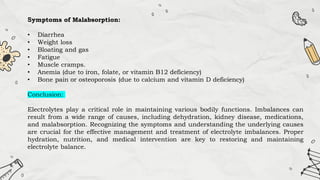

The document explains cell injury and adaptation, highlighting the structural and functional changes that occur when cells face harmful stimuli, emphasizing homeostasis and feedback mechanisms in maintaining cellular stability. It outlines various cellular adaptive responses such as atrophy, hypertrophy, hyperplasia, metaplasia, and dysplasia, as well as irreversible cell injury mechanisms leading to cell death via necrosis or apoptosis. Additionally, it describes conditions such as acidosis and alkalosis, electrolyte balance, and the importance of enzyme leakage as markers of tissue damage.