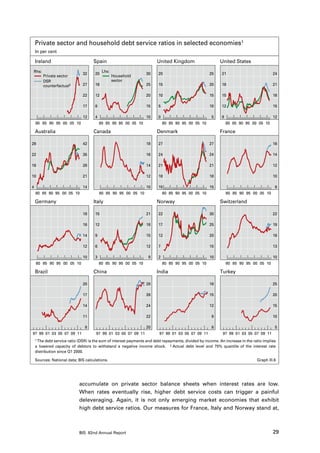

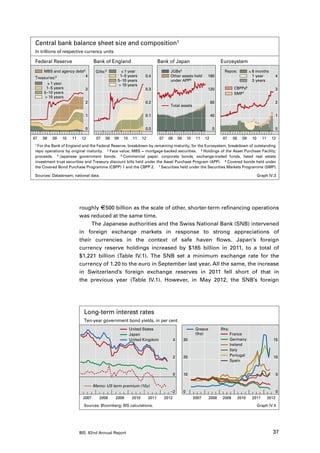

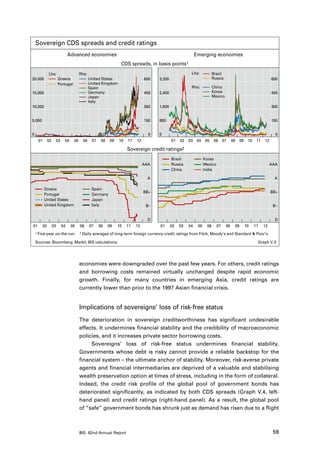

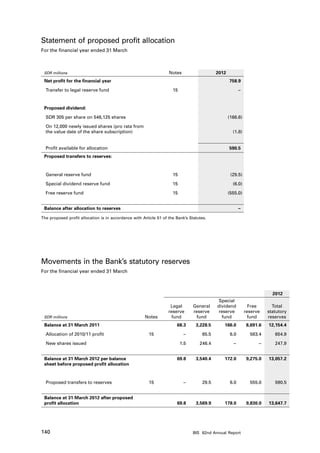

The document is the 82nd Annual Report of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS). It contains six chapters that analyze the state of the global economy and policy challenges. Chapter I discusses structural challenges persisting from the financial crisis, the heavy burden on central banks, deteriorating fiscal outlooks, changes in the financial sphere, and issues facing European monetary union. Chapter II reviews the slowing global recovery in 2011 and issues like high commodity prices and the intensifying euro area sovereign debt crisis. Chapter III examines the need for structural adjustment and rebalancing of growth. Chapter IV analyzes monetary policy limits and challenges of prolonged accommodation. Chapter V focuses on restoring fiscal sustainability and sovereigns regaining their risk-free status. Finally, Chapter VI