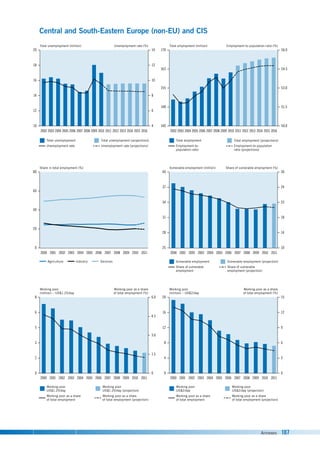

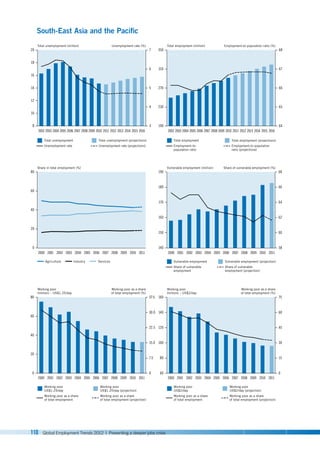

This document is the International Labour Organization's Global Employment Trends 2012 report, which analyzes global and regional employment trends and projections. The key points are:

1) The global economy has been rapidly weakening since 2011 due to fiscal austerity measures and financial turmoil in developed economies. Short-term projections show continued weak growth worldwide.

2) Unemployment rates remain high globally while employment growth has slowed. The number of working poor and those in vulnerable employment has also increased significantly.

3) All regions face challenges, but developing regions have grown more rapidly than developed economies recently. East Asia remains the strongest performing region, while youth unemployment is a major problem in many countries.

4) To prevent a

![Bibliography 89

Bibliography

Admati, A.R. et al. 2011. Fallacies, irrelevant facts, and myths in the discussion of capital regulation:

Why bank equity is not expensive (Stanford, CA, Stanford Graduate School of Business).

Ballon, P.; Ernst, E. Forthcoming. Patterns of global growth (Geneva, ILO).

Bassanini, A.; Duval, R. 2006. “The determinants of unemployment across OECD countries”, in

OECD Economic Studies, Vol. 42, No. 1, pp. 7–86.

BPS Statistics Indonesia. 2011. “Labor force situation in Indonesia, Jakarta”. Available at: http://

www.bps.go.id/brs_file/naker_07nov11.pdf [Nov. 2011].

Casselman, B.; Lahart, J. 2011. “Companies shun investment, hoard cash”, in Wall Street Journal.

Available at: http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424053111903927204576574720017009

568.html [17 Sep. 2011].

Chowdhury, S. 2011. “Employment in India: What does the latest data show?”, in Economic and

Political Weekly, Vol. XLVI, No. 32, pp. 23–26.

Cochrane, J.H. 2008. “Financial markets and the real economy”, in R. Mehra (ed.): Handbook of the

equity risk premium (Elsevier Science), pp. 237–330.

—. 1991. “Production-based asset pricing and the link between stock returns and economic

fluctuations”, in Journal of Finance, Vol. 46, No. 1, pp. 207–234.

Eichengreen, B.; Park, D.; Shin, K. 2011. When fast growing economies slow down: International

evidence and implications for China (Cambridge, MA, National Bureau of Economic Research).

Ernst, C.; Iturriza, A. 2011. Tackling deforestation in Mozambique: Reconciling the social, economic

and environmental agenda, paper presented at the 14th ILO Regional Seminar for Labour

Based Practitioners, Accra, Ghana, 5–9 Sept.

Ernst, E. 2011a. “The future of finance: Scenarios of financial sector reforms and their labour market

implications”, in The global crisis. Causes, responses and challenges (Geneva, International Labour

Office) pp. 223–240.

—. 2011b. Determinants of unemployment dynamics. Economic factors, labour market institutions and

financial development (Geneva, International Institute for Labour Studies).

Hungerford, T.; Gravelle, J.G. 2010. Business investment and employment tax incentives to stimulate

the economy (Washington, DC, Congressional Research Service).

Institute of International Finance (IIF). 2010. Interim report on the cumulative impact on the global

economy of proposed changes in the banking regulatory framework (Washington, DC).

Interindustry Economic Research Fund. 2011. Development of scenarios gauging the effects of

increased investment in the United States on growth and employment (Washington, DC).

Background paper produced for this report.

International Institute for Labour Studies (IILS). 2011. World of Work Report 2011: Making

markets work for jobs (Geneva, ILO).

—. 2010. World of Work Report 2010: From one crisis to the next? (Geneva, ILO).

—. 2009. The financial and economic crisis: A decent work response (Geneva).

International Labour Office (ILO). 2011a. The global crisis. Causes, responses and challenges (Geneva).

—. 2011b. Global Employment Trends for Youth: 2011 update (Geneva).

—. 2011c. Economically Active Population Estimates and Projections, 6th edition. Available at:

http://laborsta.ilo.org/applv8/data/EAPEP/eapep_E.html.

—. 2011d. Key Indicators of the Labour Market, 7th edition (Geneva).

—. 2011e. Growth, productive employment and decent work in the least developed countries (Geneva).

—. 2011f. Efficient growth, employment and decent work in Africa: Time for a new vision (Geneva).

—. 2011g. Empowering Africa’s peoples with decent work. Report of the Director General (Geneva).

—. 2011h. South Africa. Growth and equity through social protection and policy coherence (G20

reports) (Geneva). Available at: http://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/how-the-ilo-works/

multilateral-system/g20/lang--en/index.htm.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/internationallabourofficereport2012-121019145943-phpapp02/85/International-labour-office-report-2012-90-320.jpg)