The document is the February 2014 Monetary Policy Report from the Federal Reserve. It discusses recent economic and financial developments. Key points:

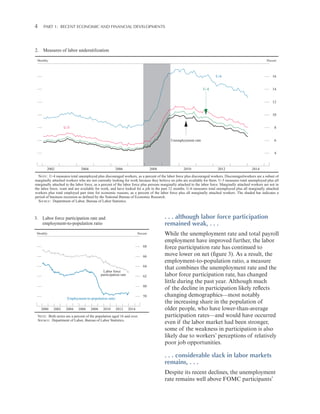

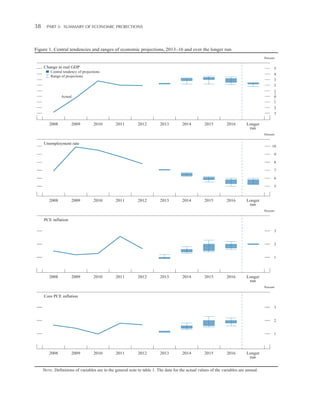

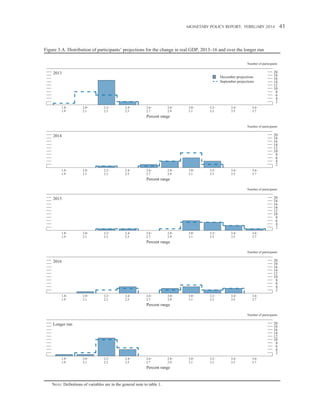

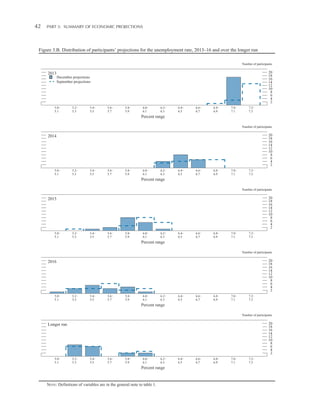

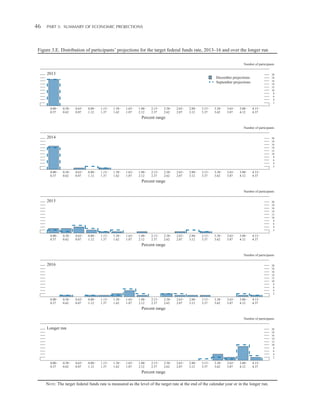

- The labor market continued improving in the second half of 2013 and early 2014, with employment gains averaging 175,000 per month and unemployment falling to 6.6%. However, unemployment remains above sustainable levels.

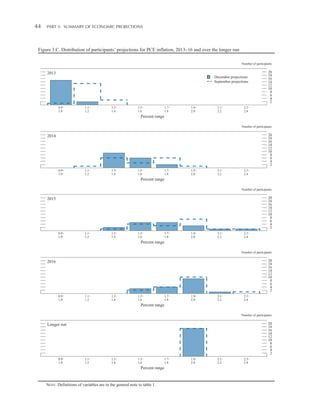

- Inflation remained low at 1% over the last half of 2013, below the Fed's 2% target, but some factors were transitory. Inflation expectations have remained steady.

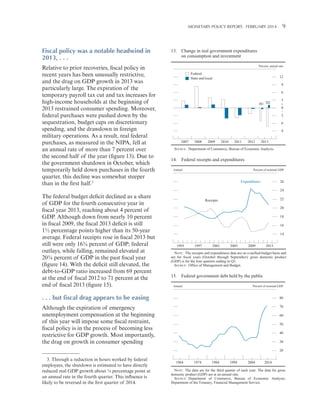

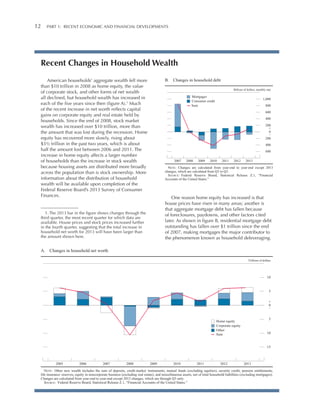

- Economic growth picked up in the second half of 2013 to an annual rate of 3.75%, as fiscal policy restraint lessened and financial conditions remained supportive.