Morphology of

microorganisms.

Bacterial ultrastructure.

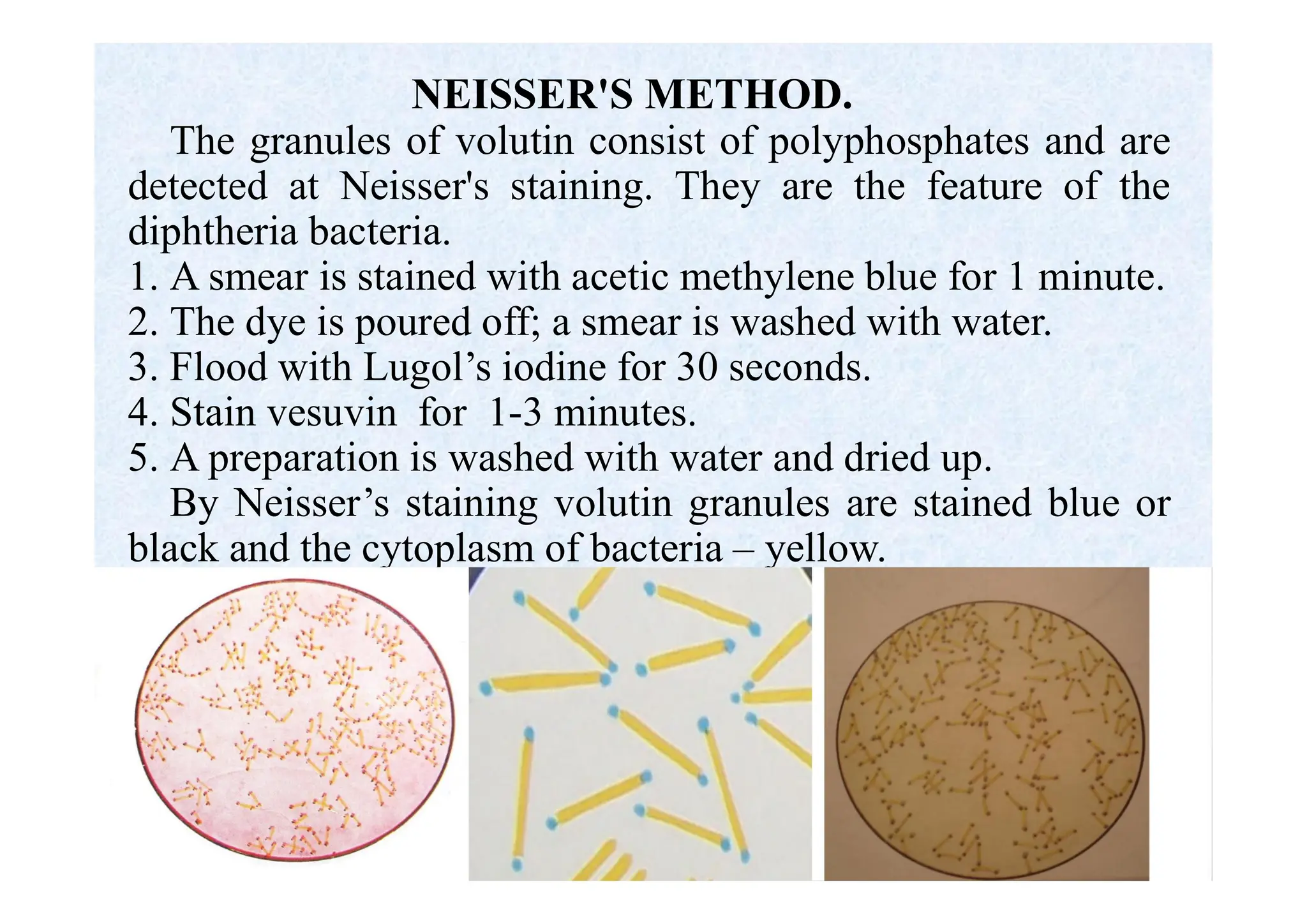

Complex staining methods.

Lecturer:

Associate Professor of the MicrThe Subject and Problems of Microbiology.

Microbiology (Gk. mikros small, bios life, logos science Classification and Morphology of MicroorganismsTaxonomy and classifications of microbes