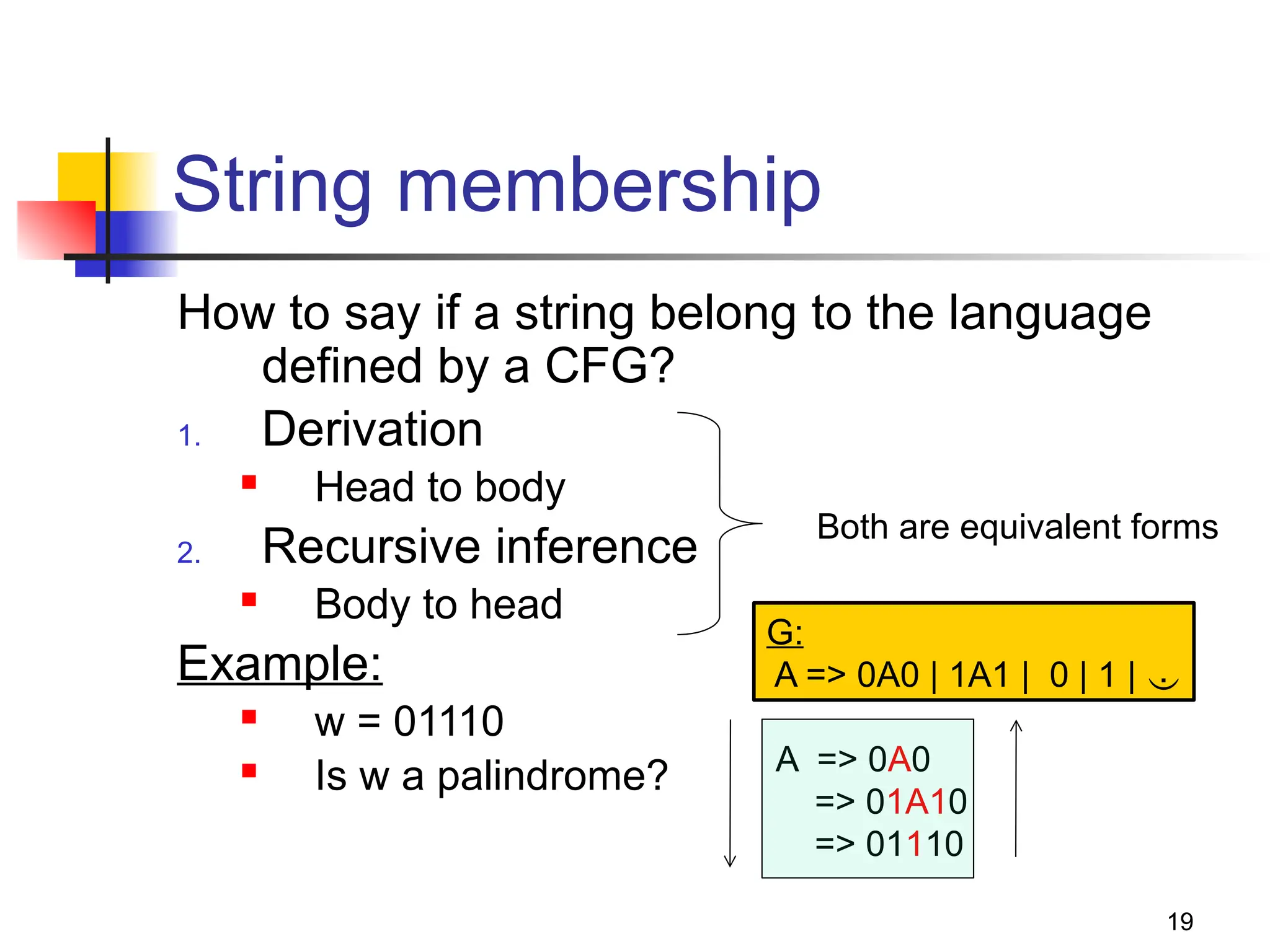

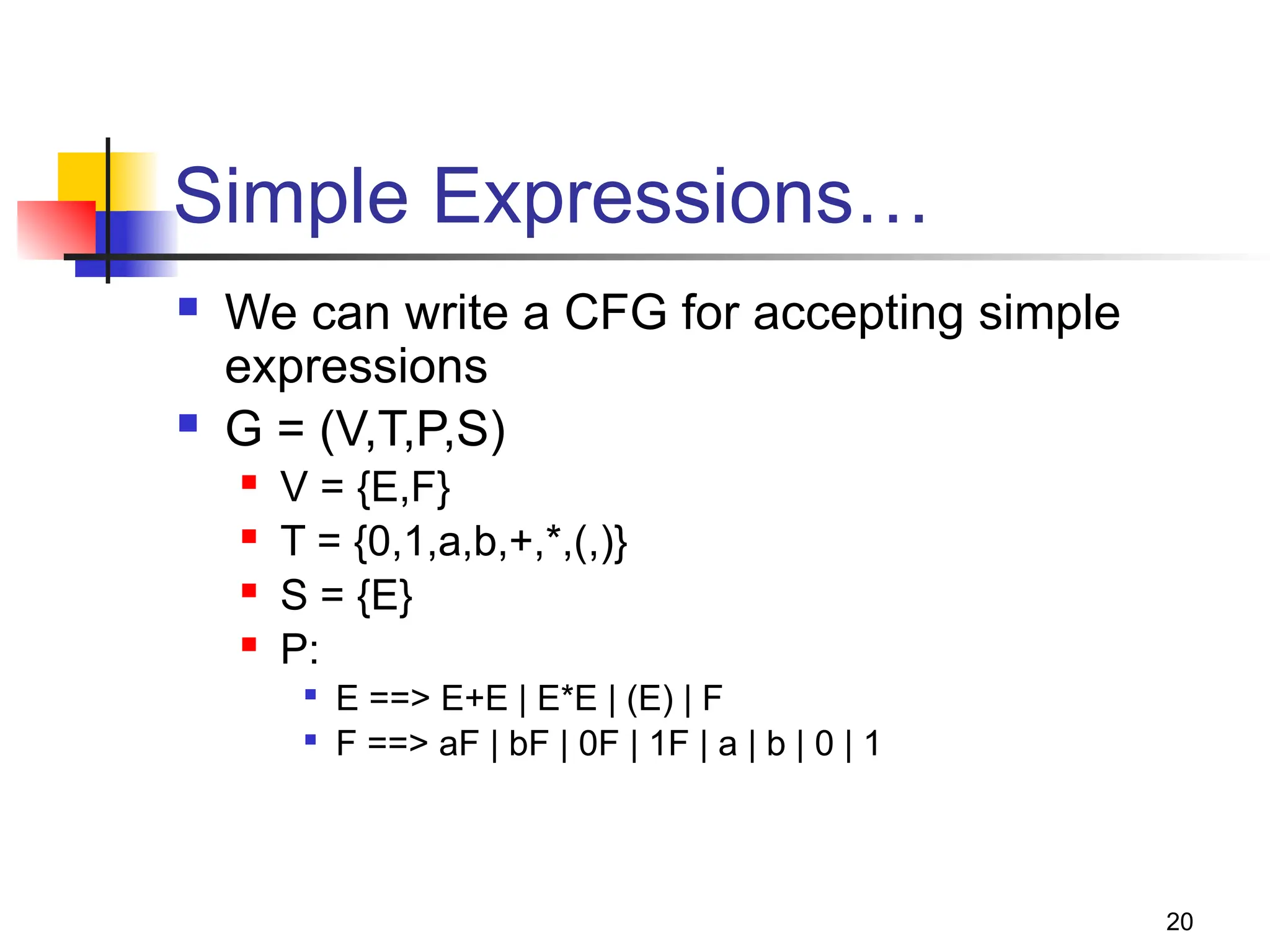

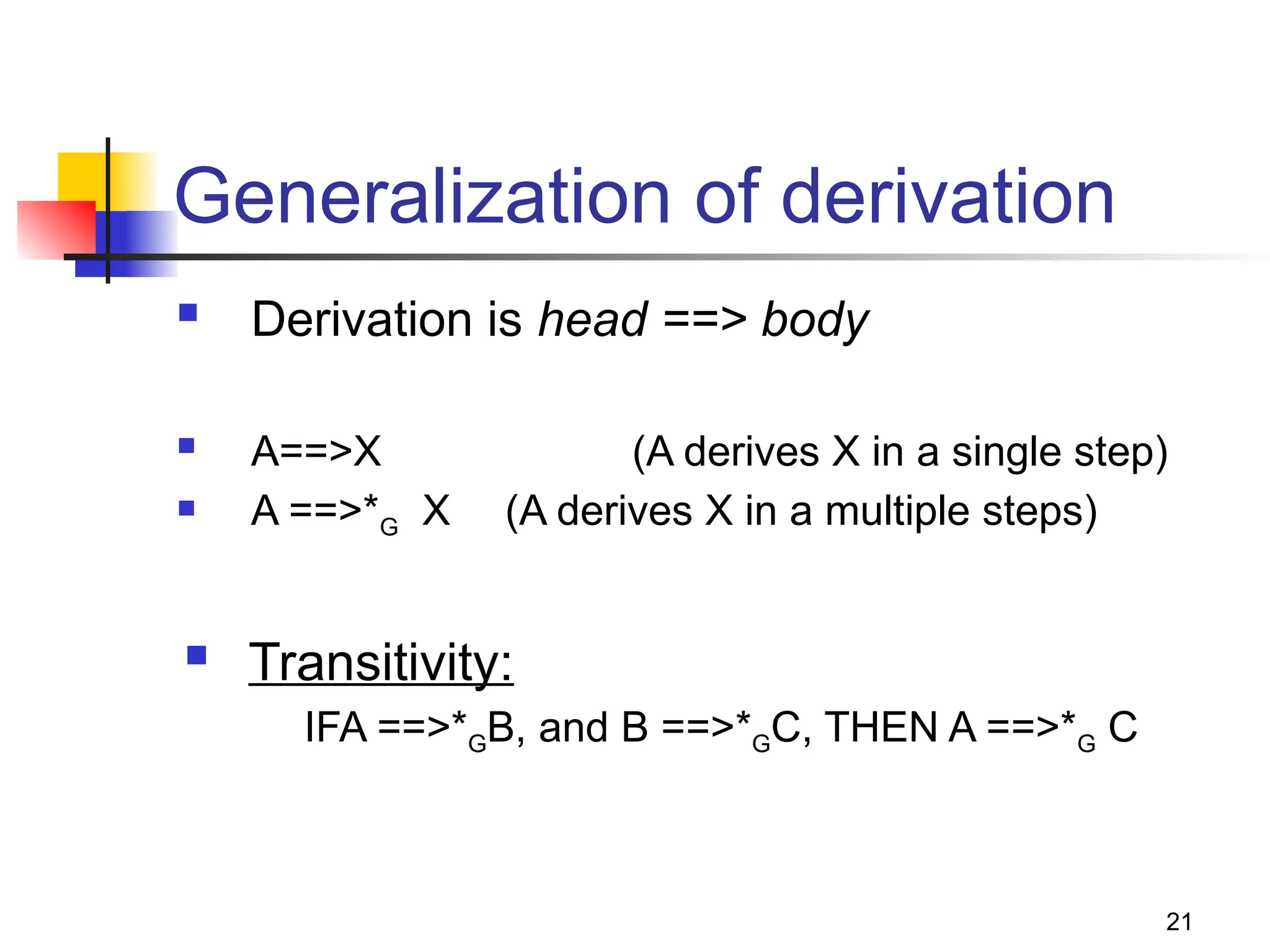

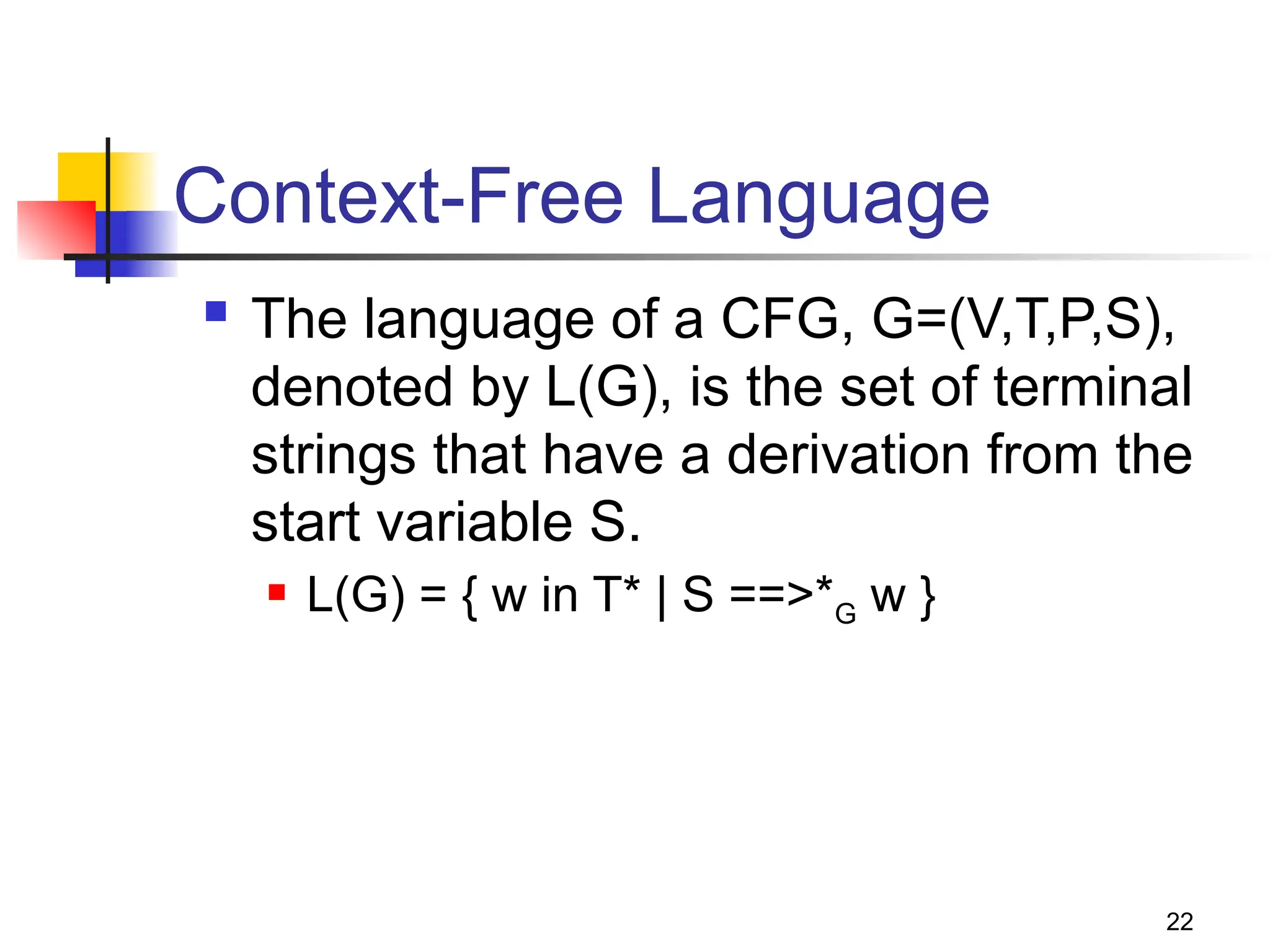

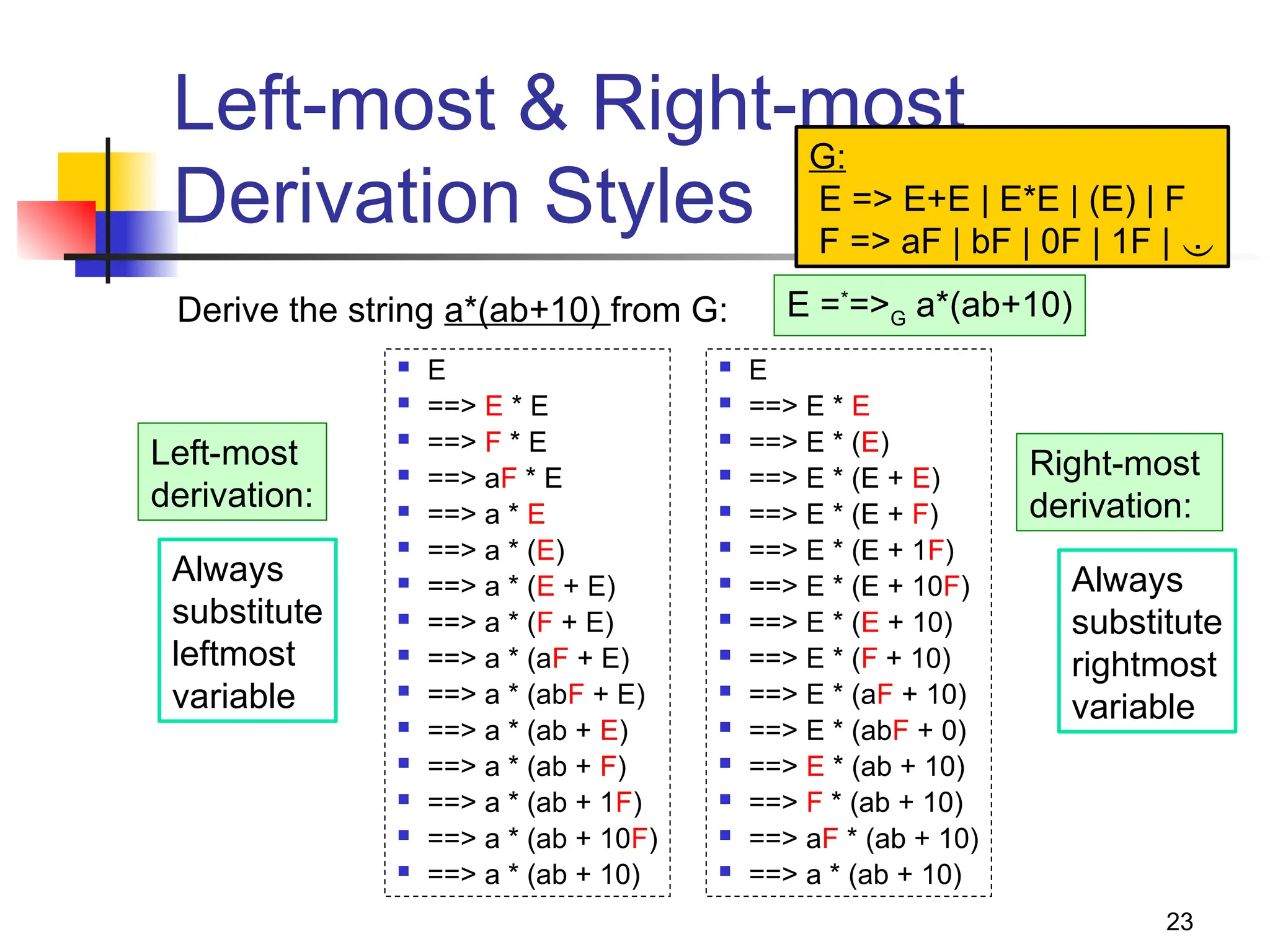

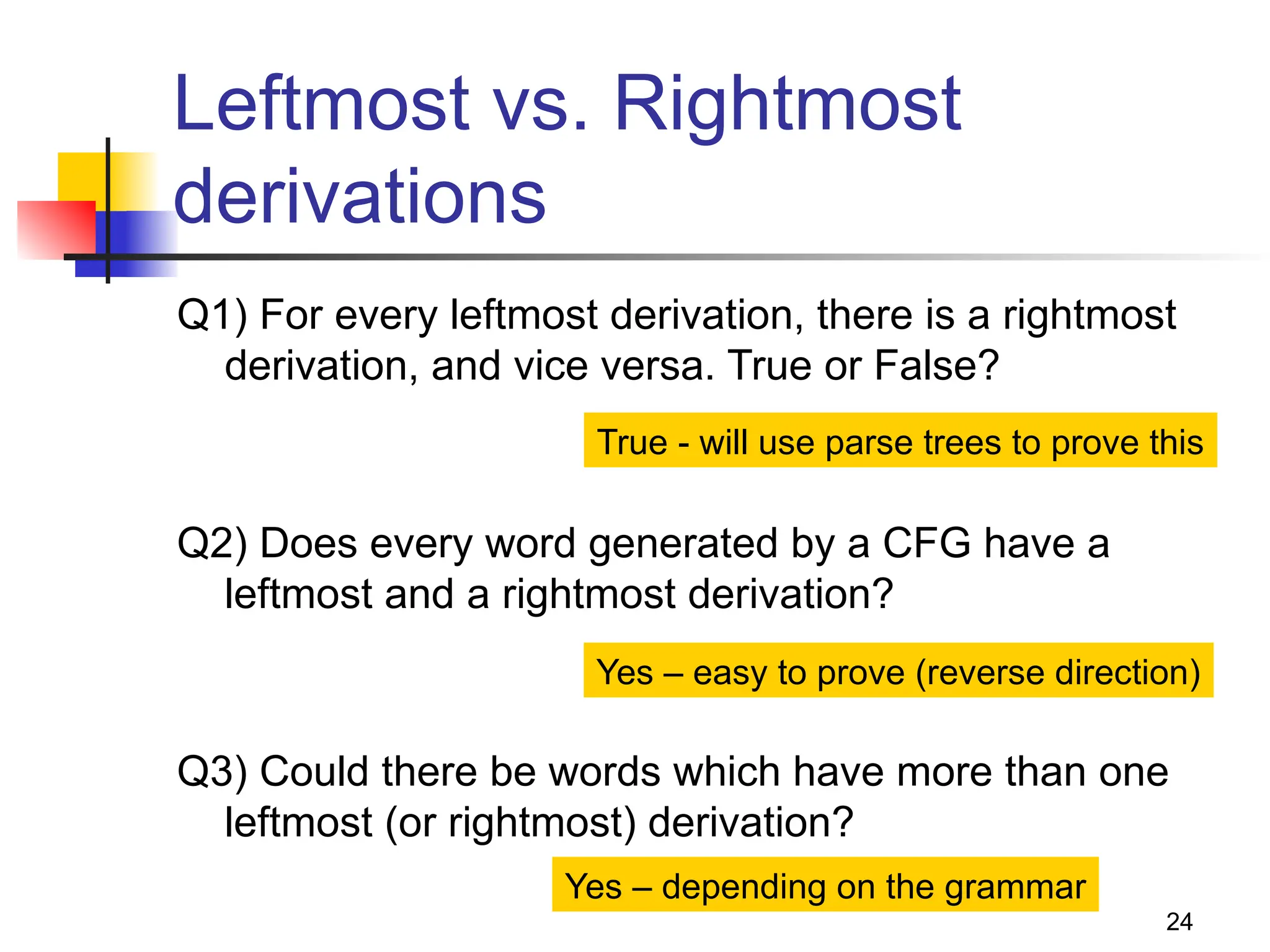

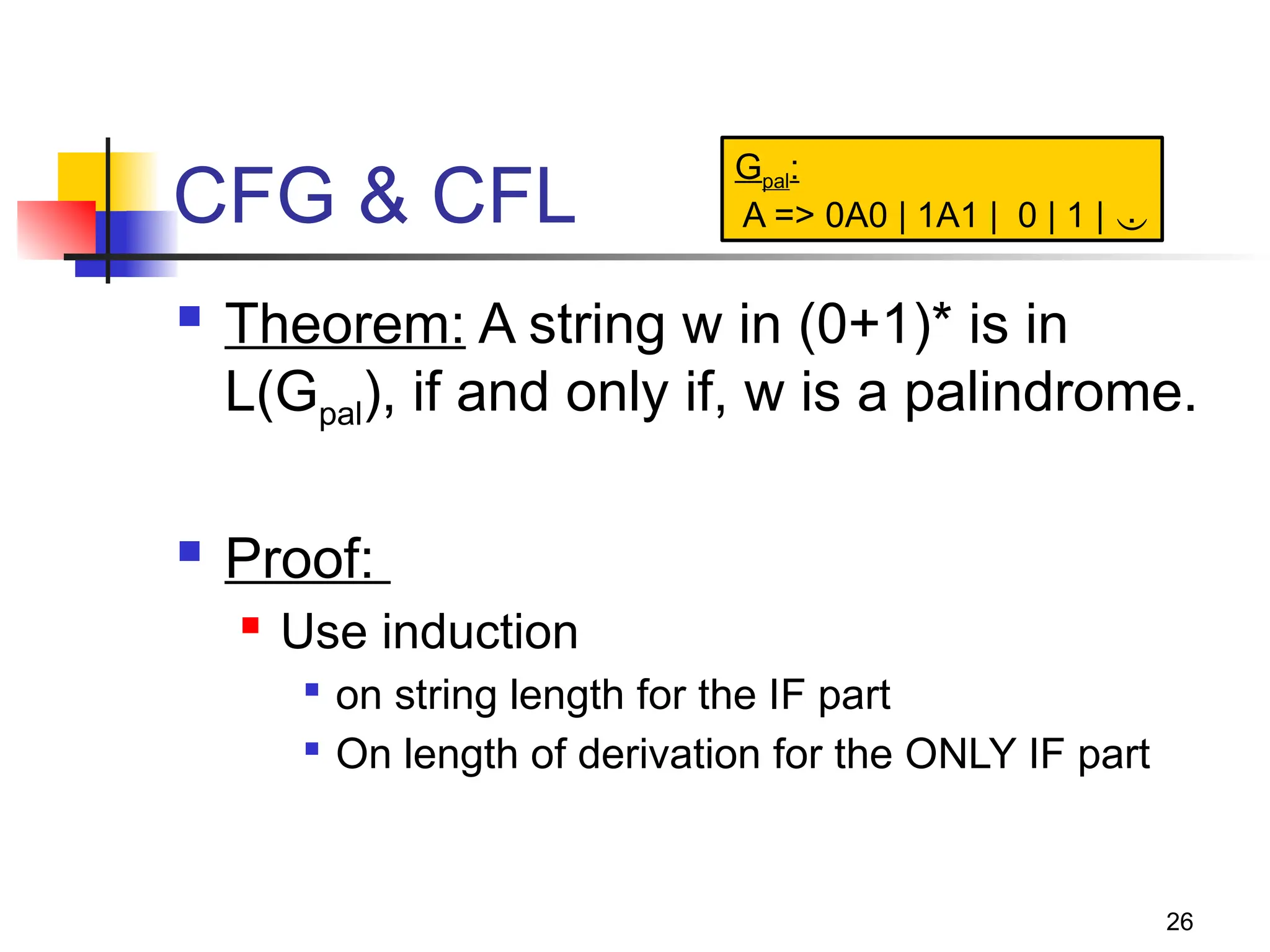

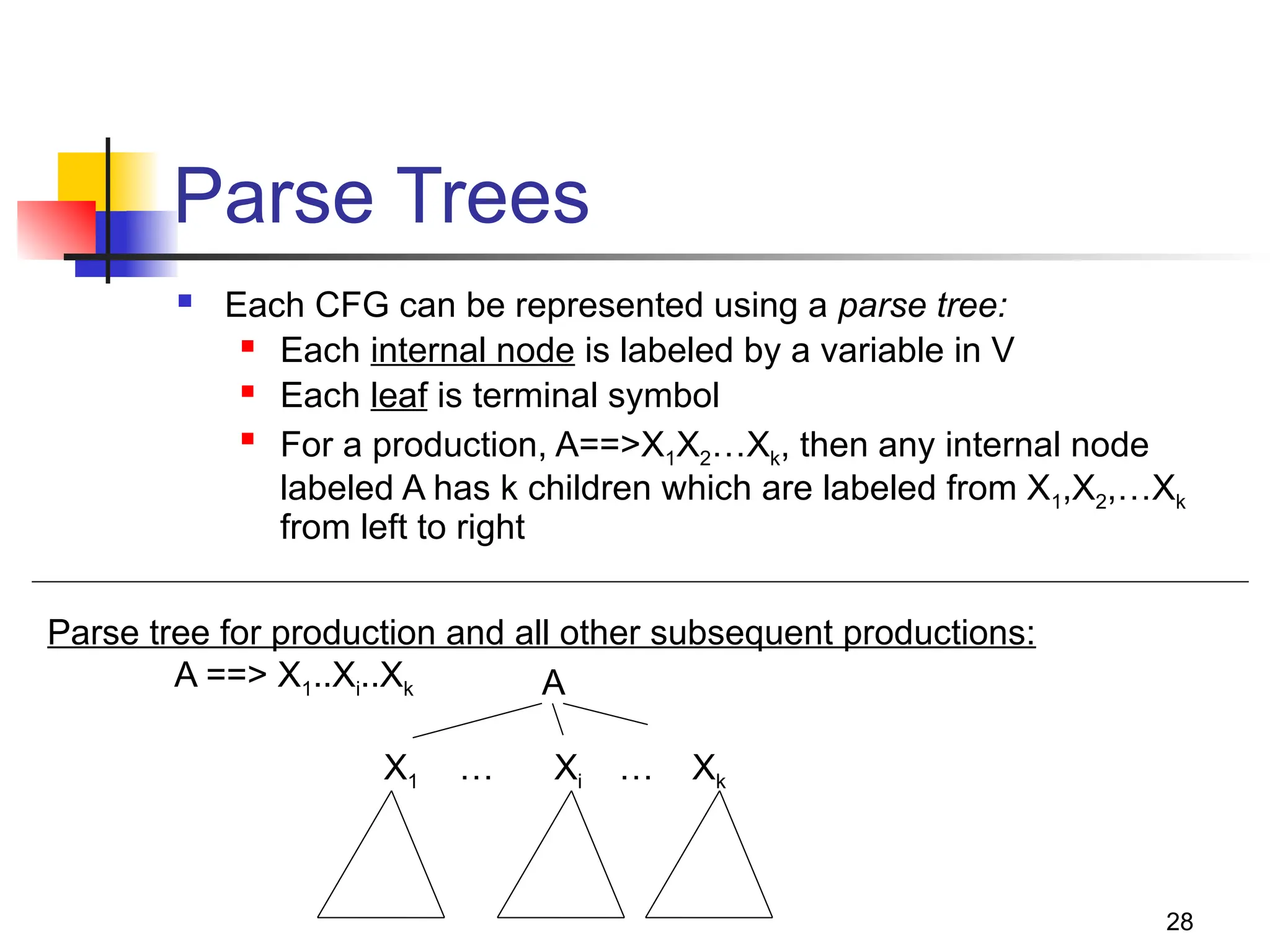

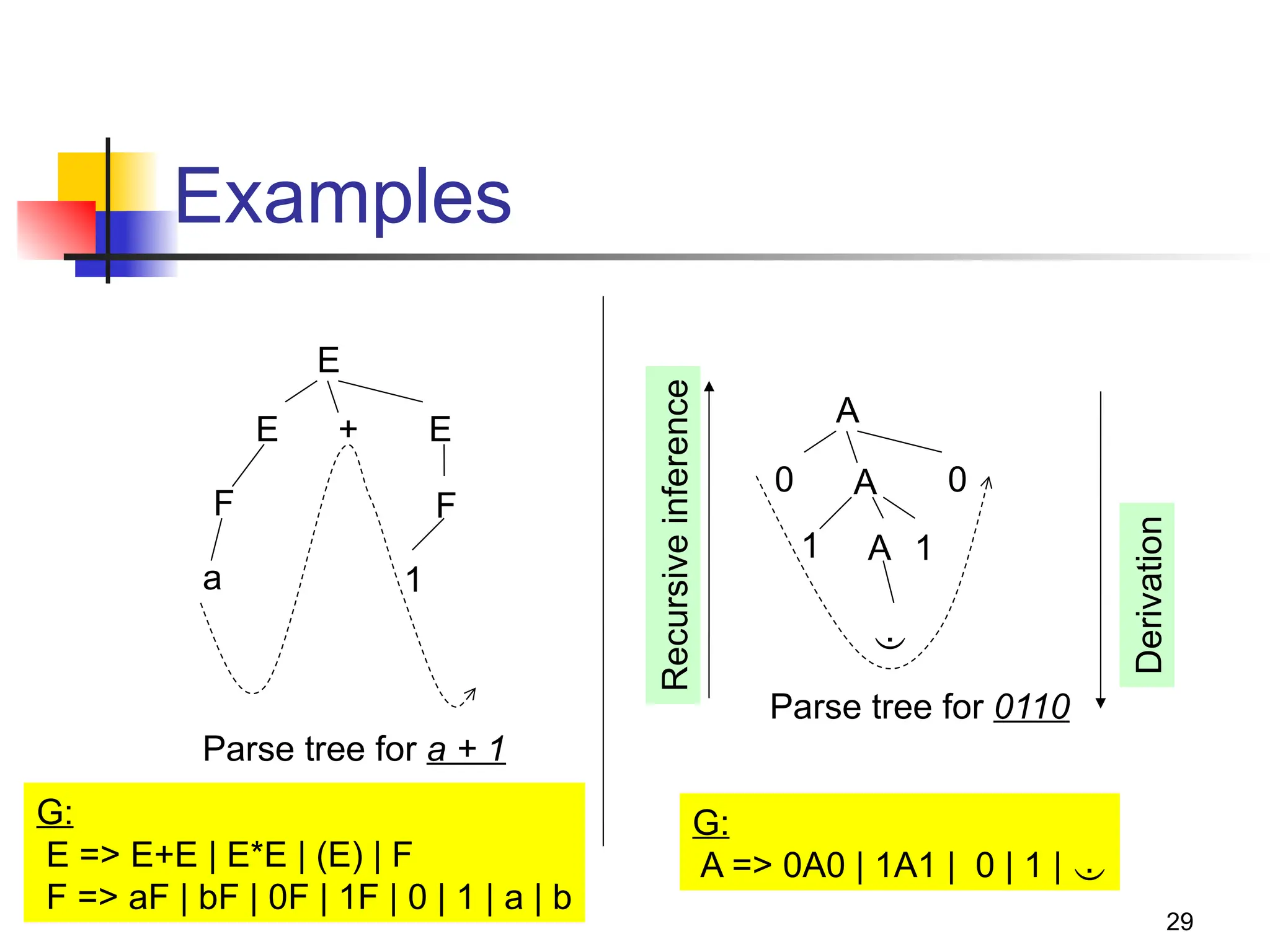

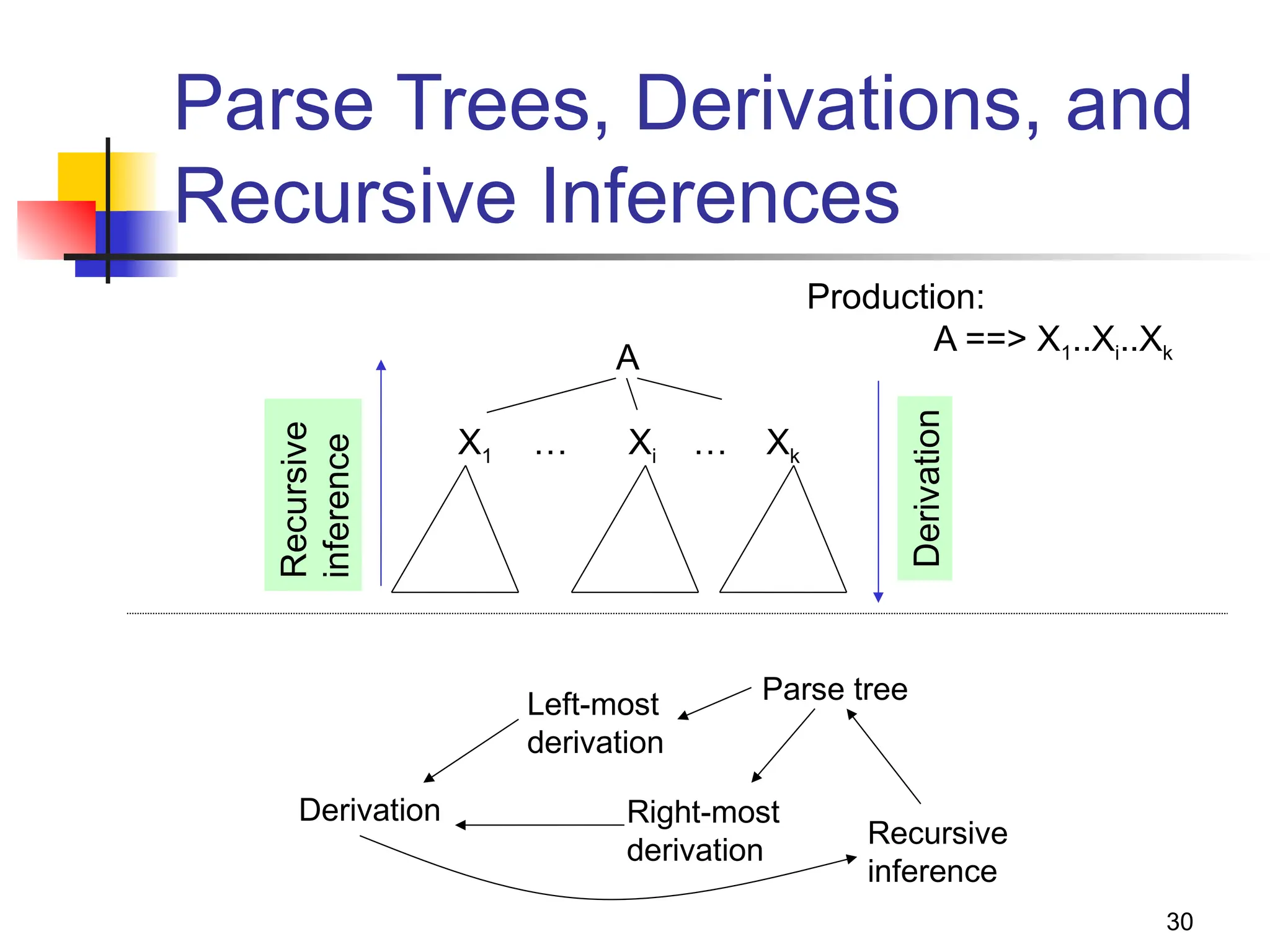

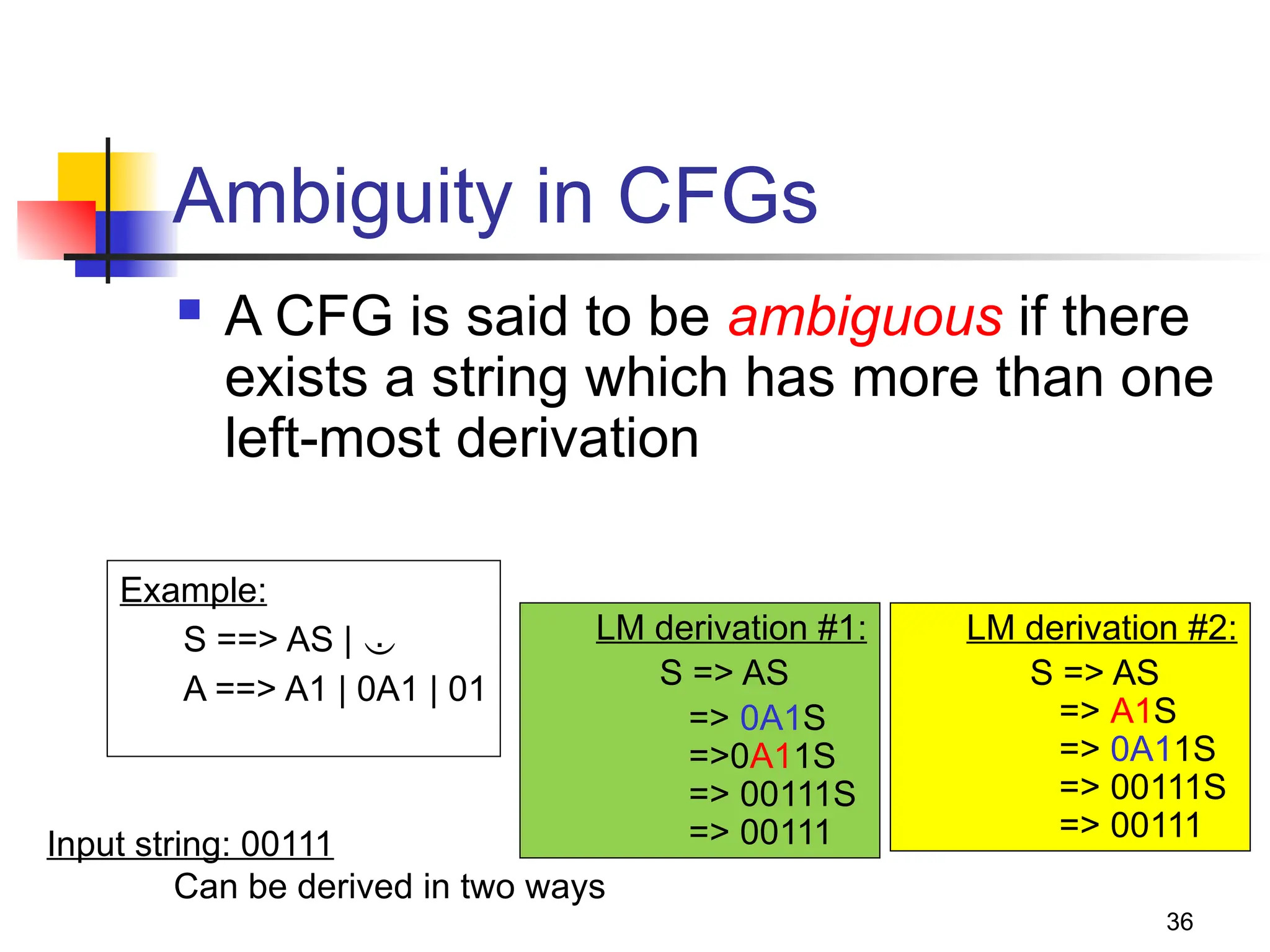

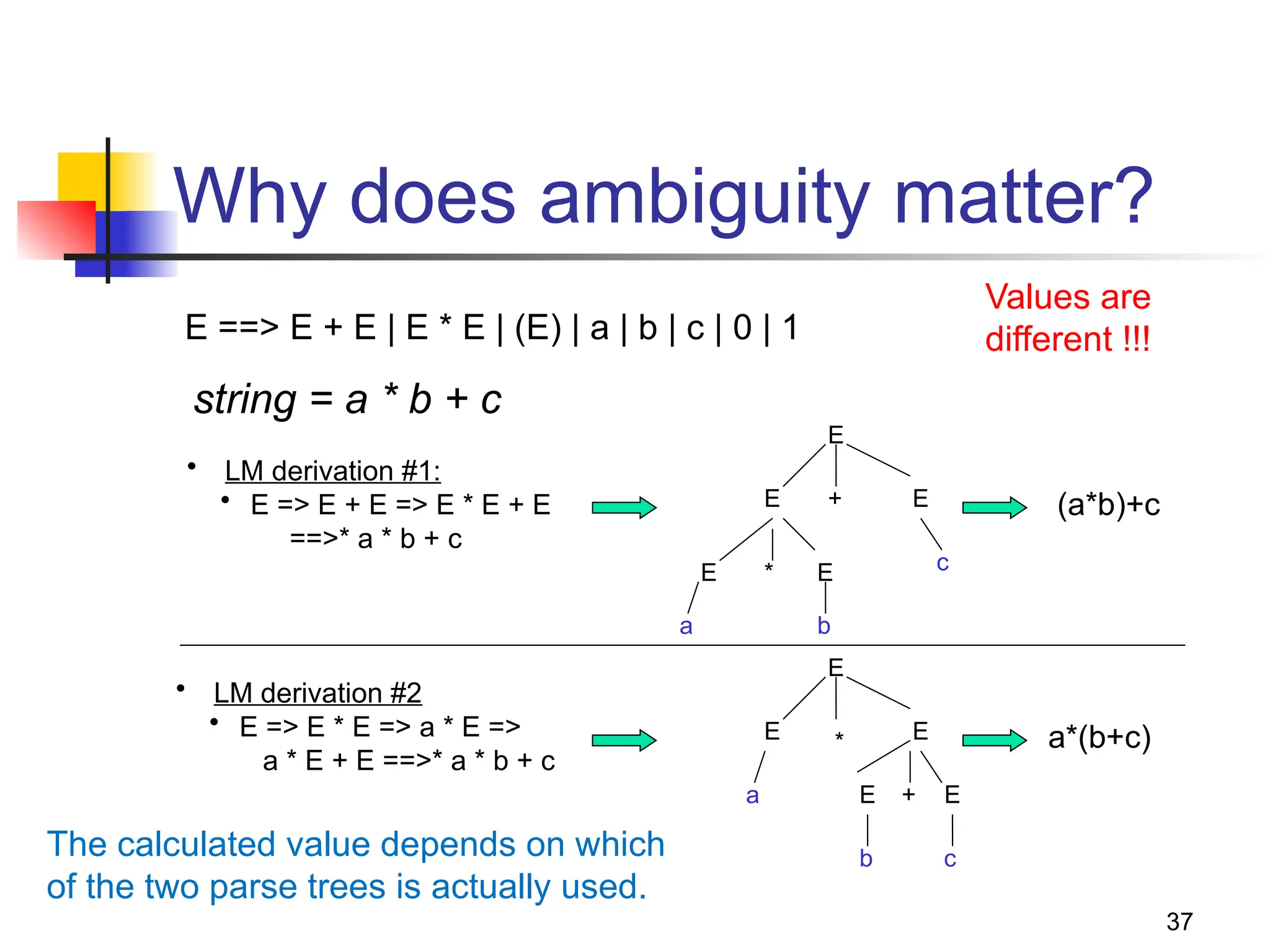

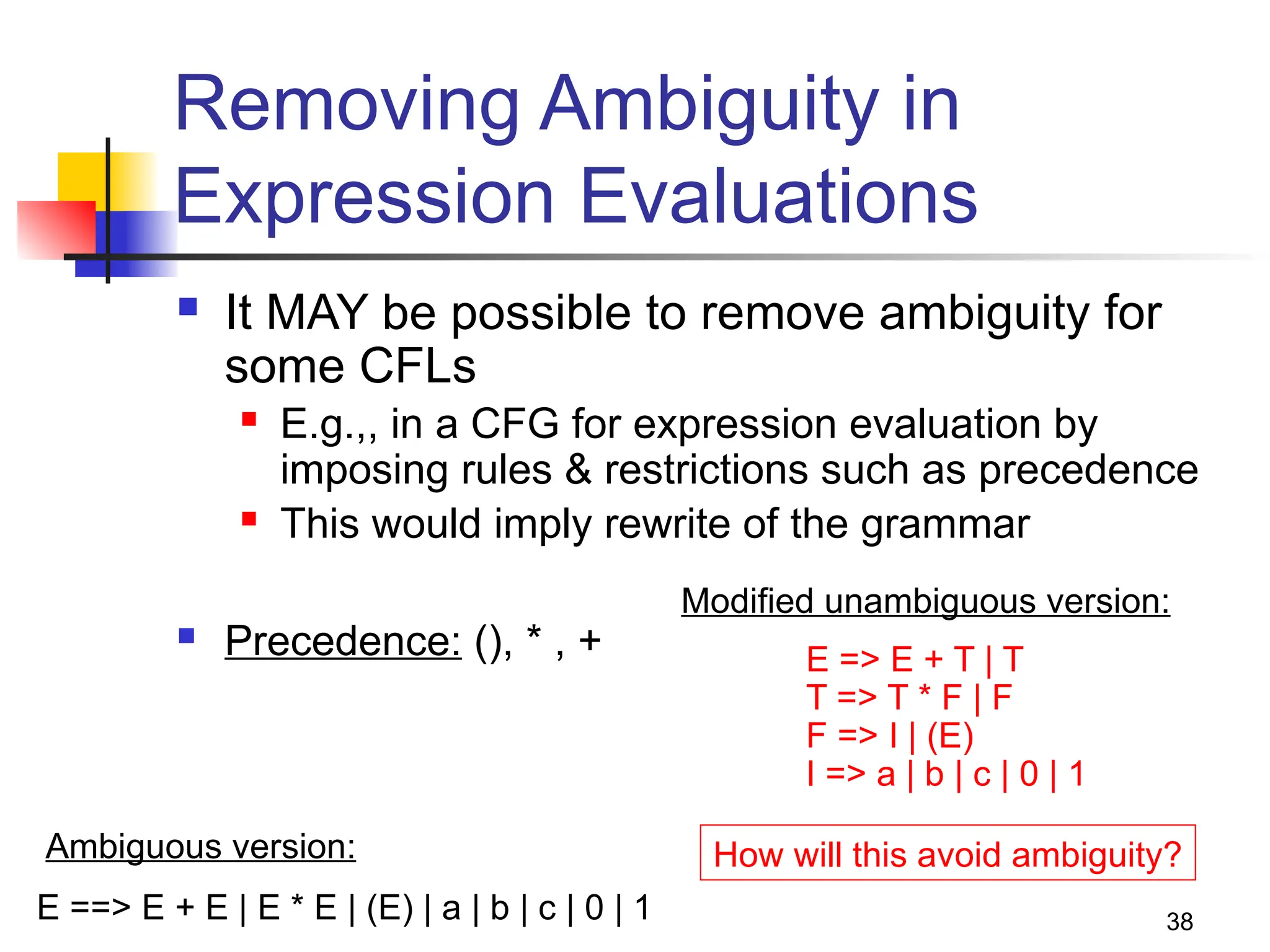

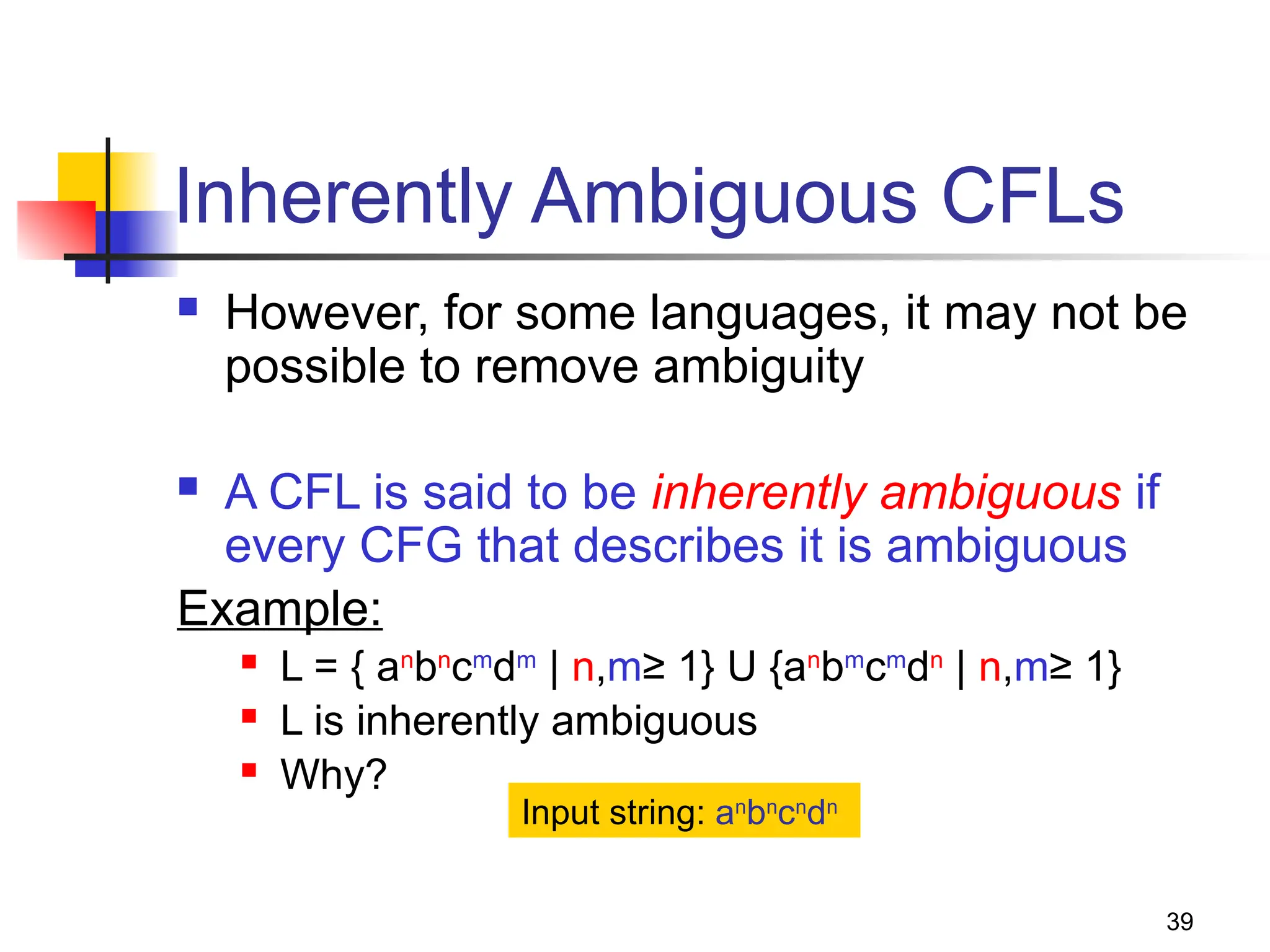

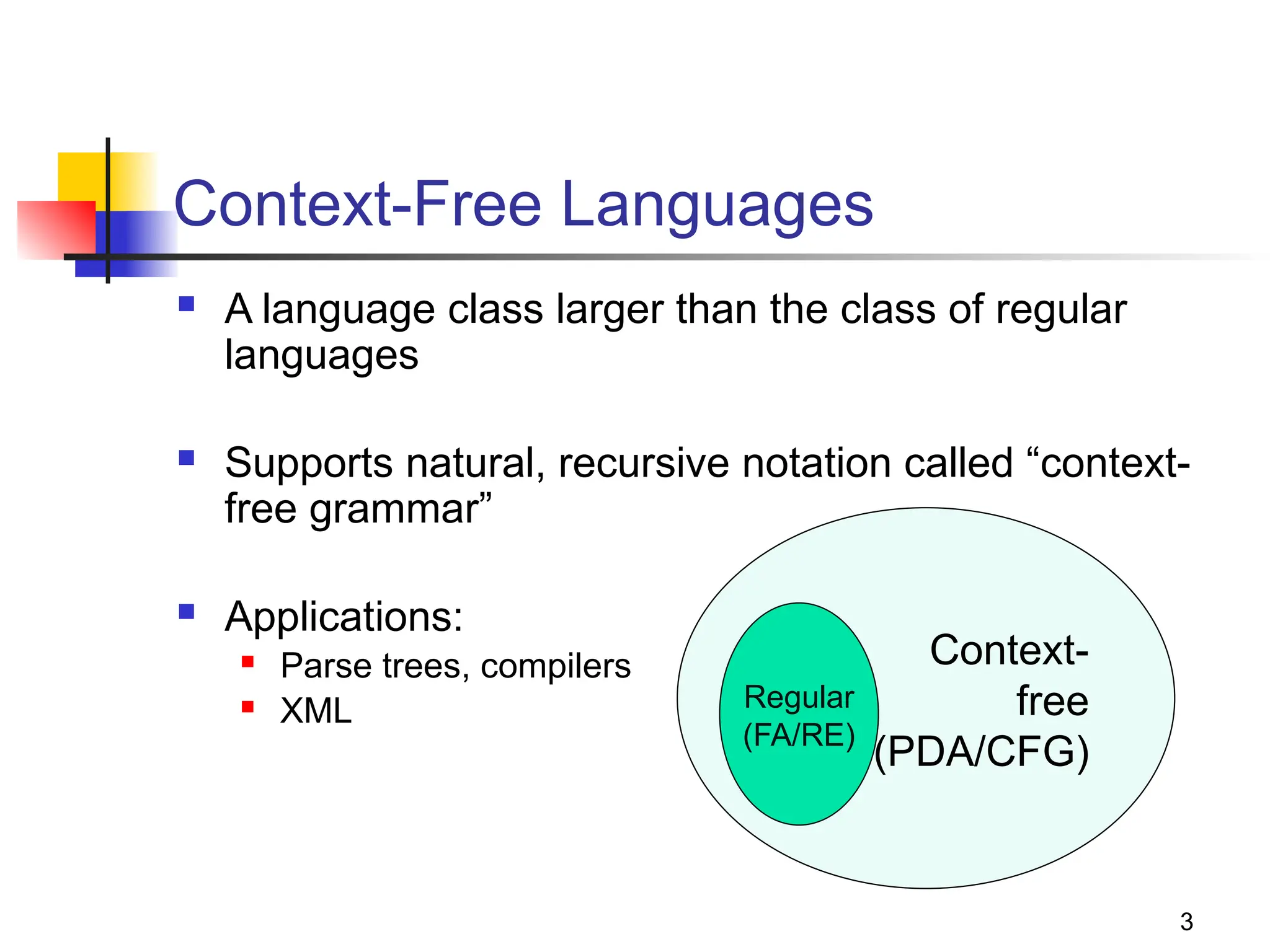

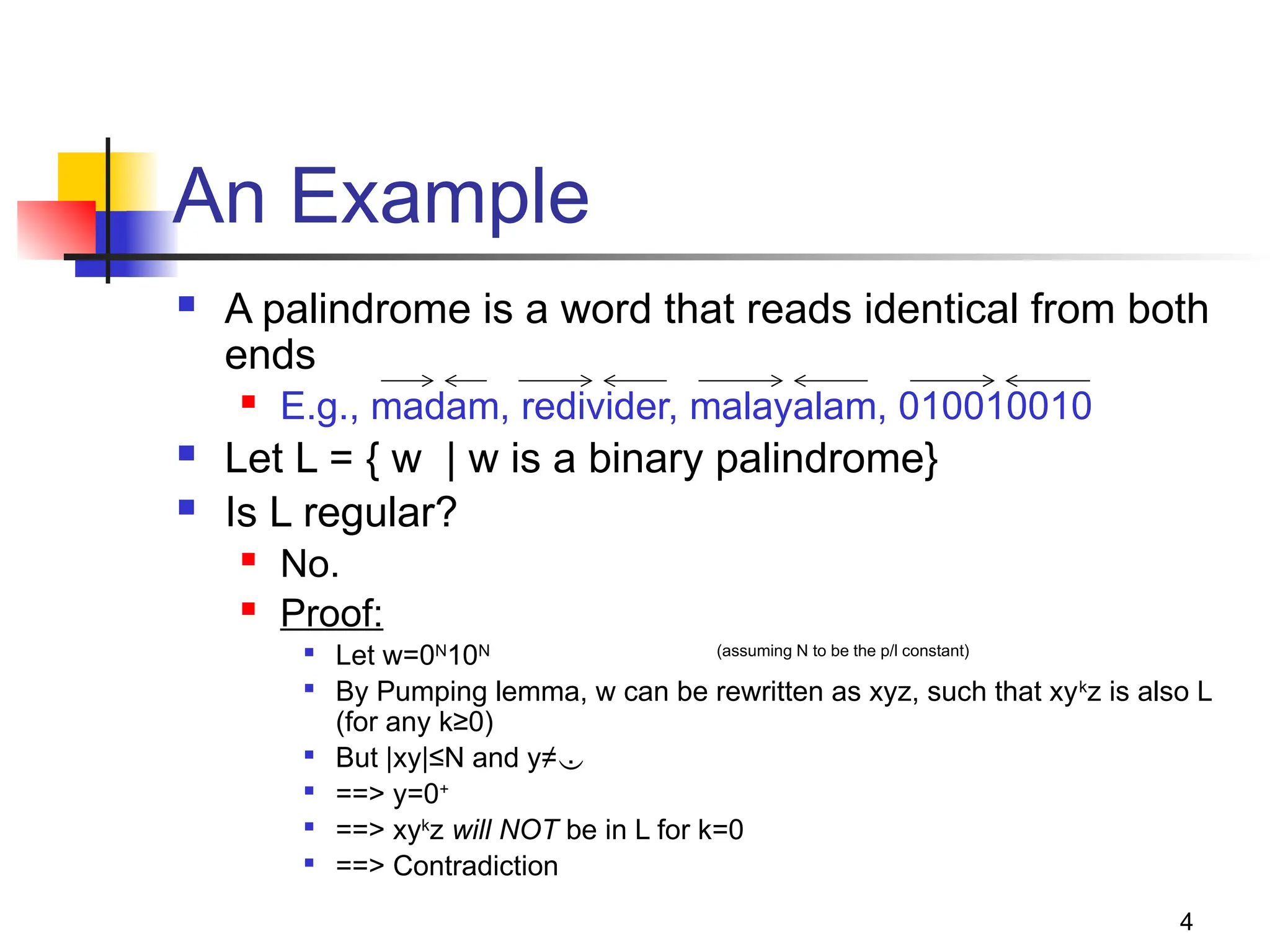

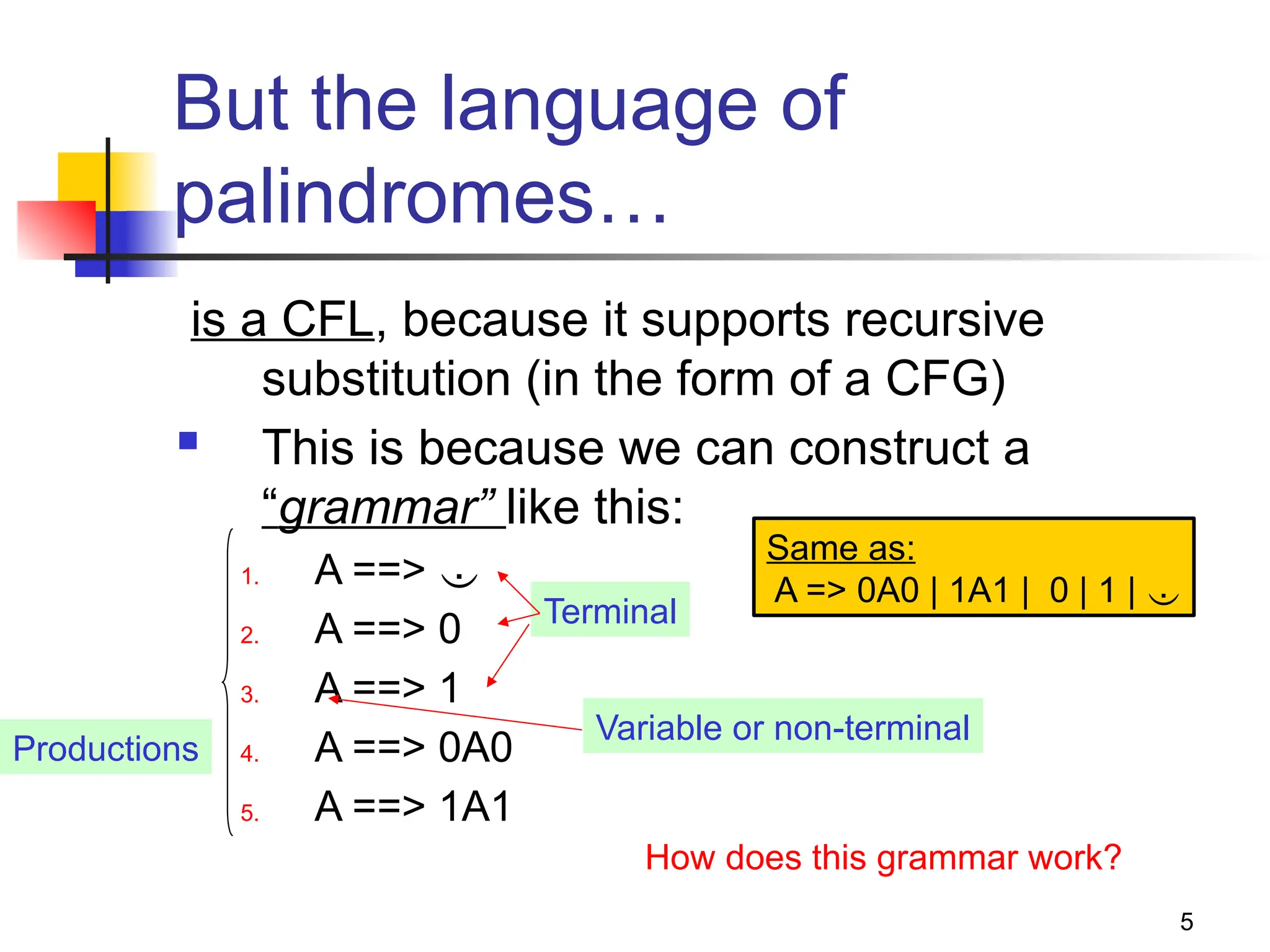

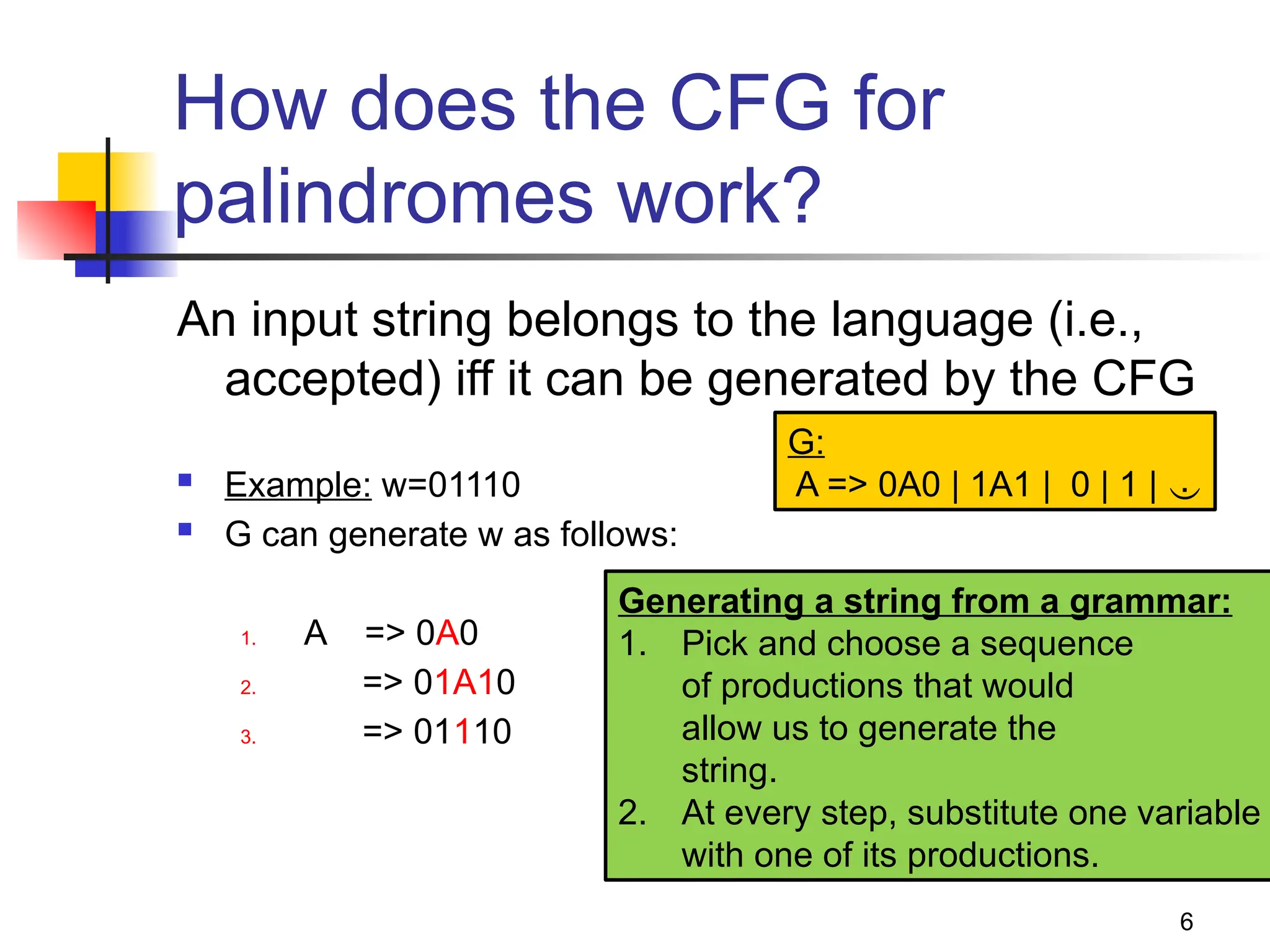

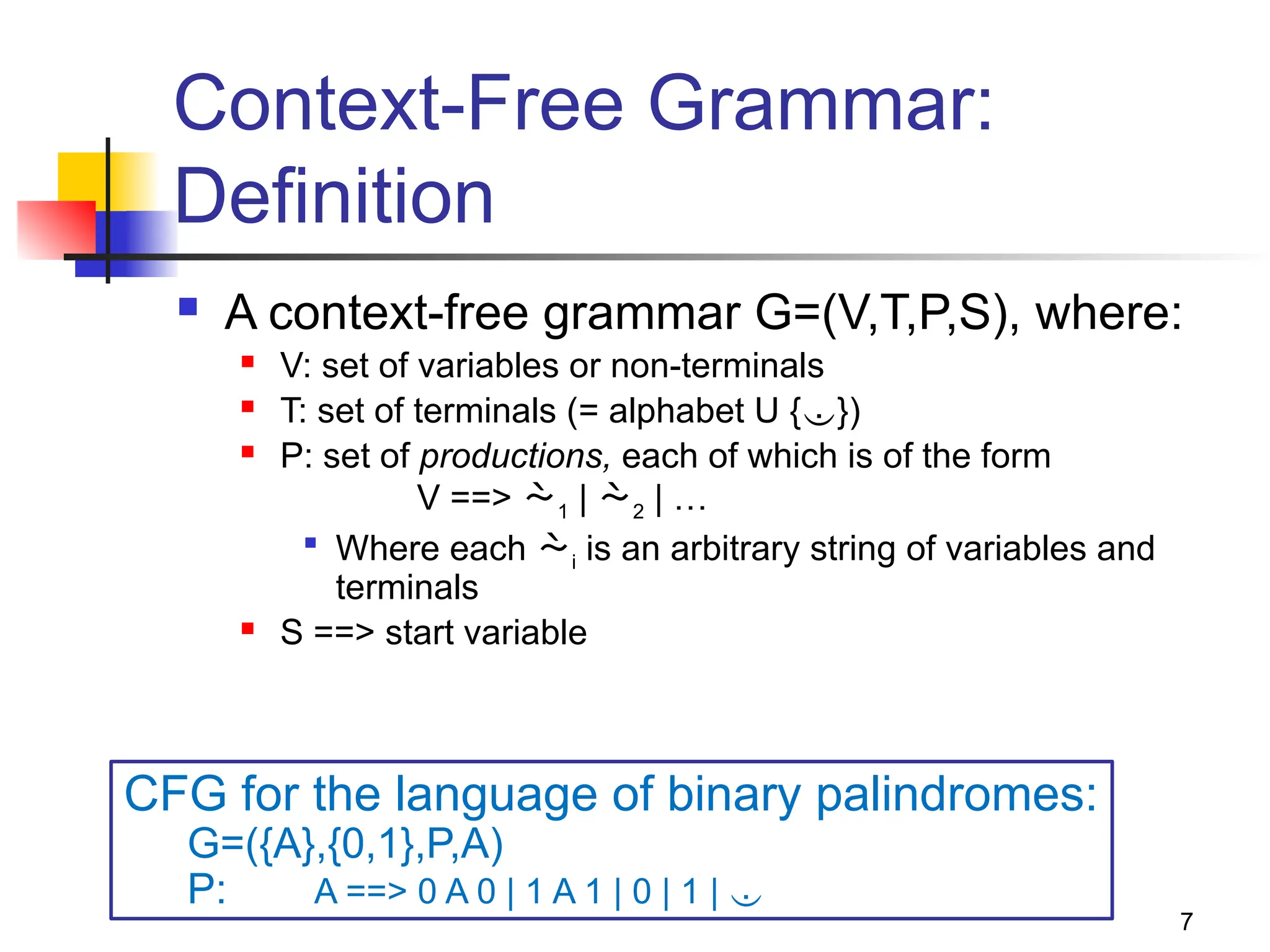

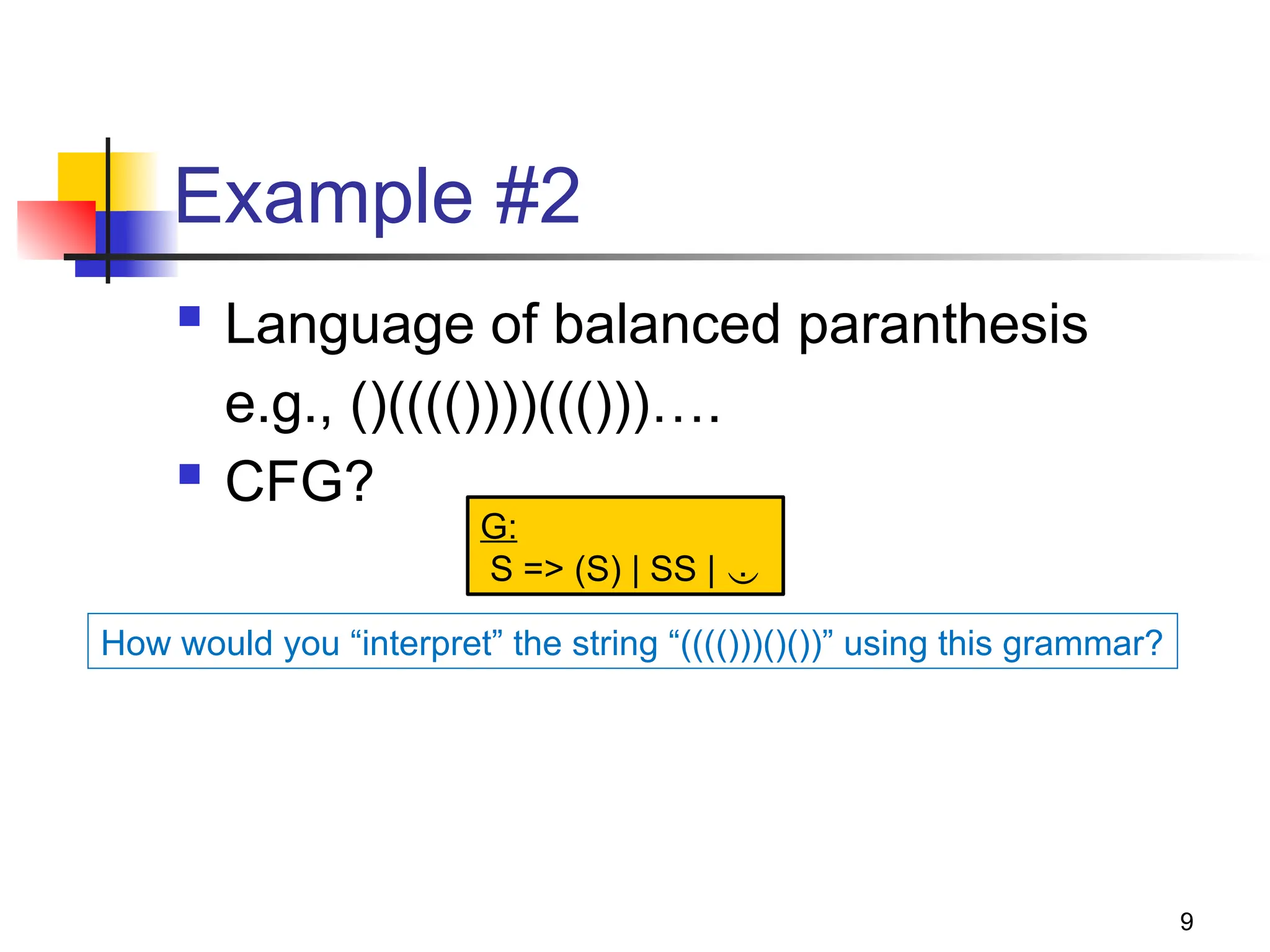

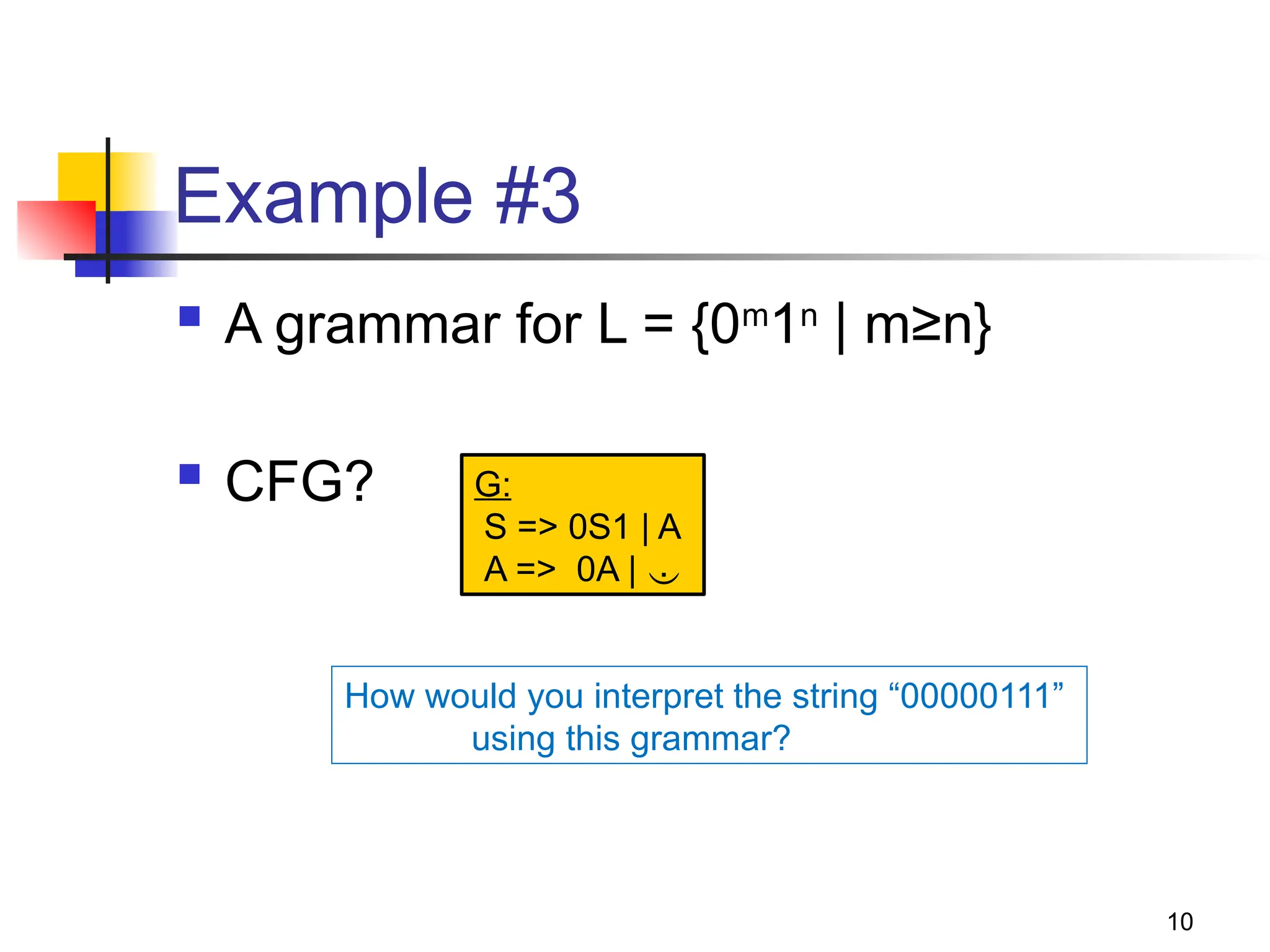

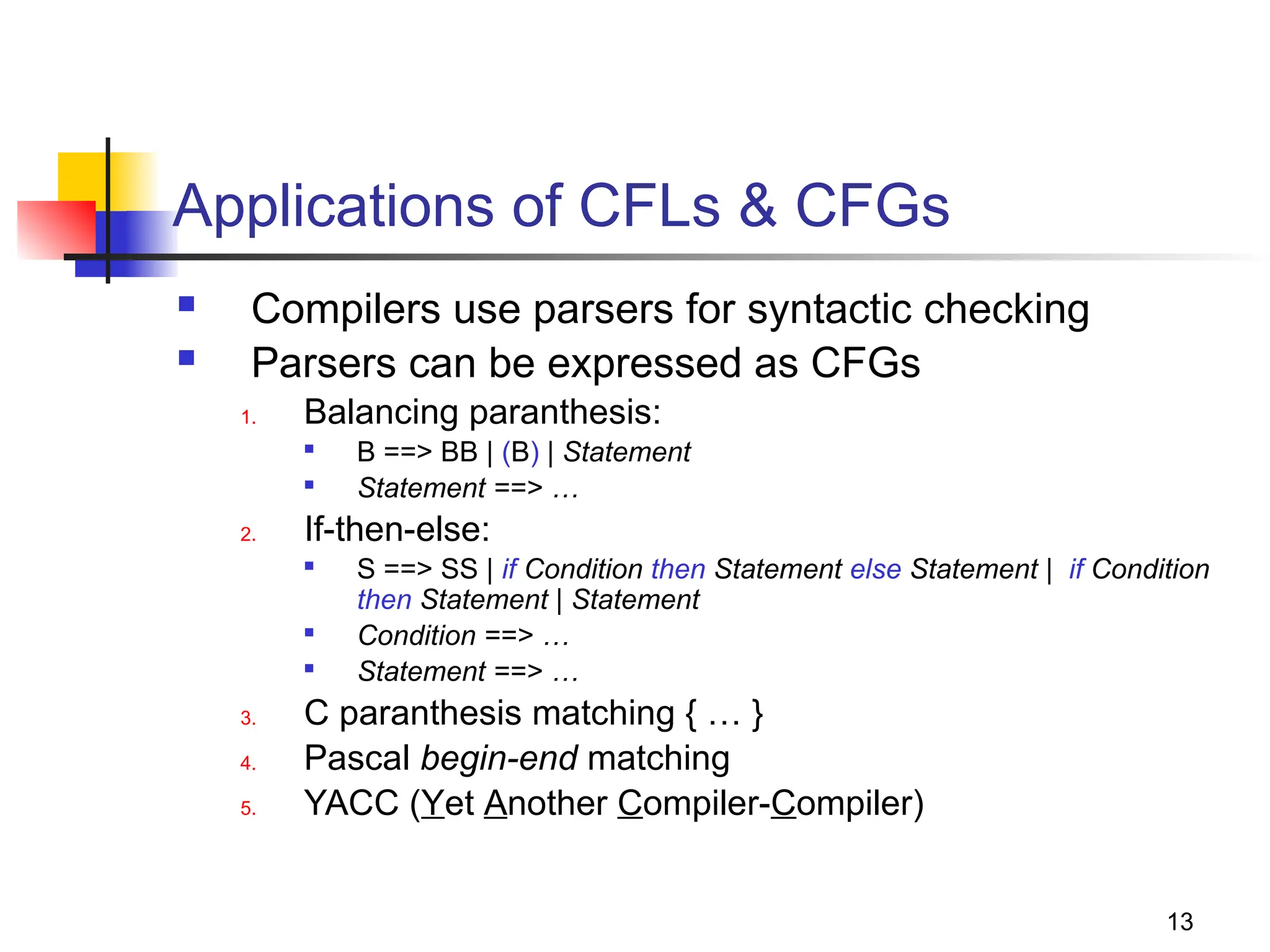

The document discusses context-free languages (CFLs) and context-free grammars (CFGs), illustrating their differences from regular languages and their applications in parsing and programming. It covers the structures of CFGs, the derivation process, examples of CFGs, and concepts like ambiguity and how to address it. Key topics include the generation of palindromes, the grammar for balanced parentheses, and the formal definitions and implications of context-free languages.

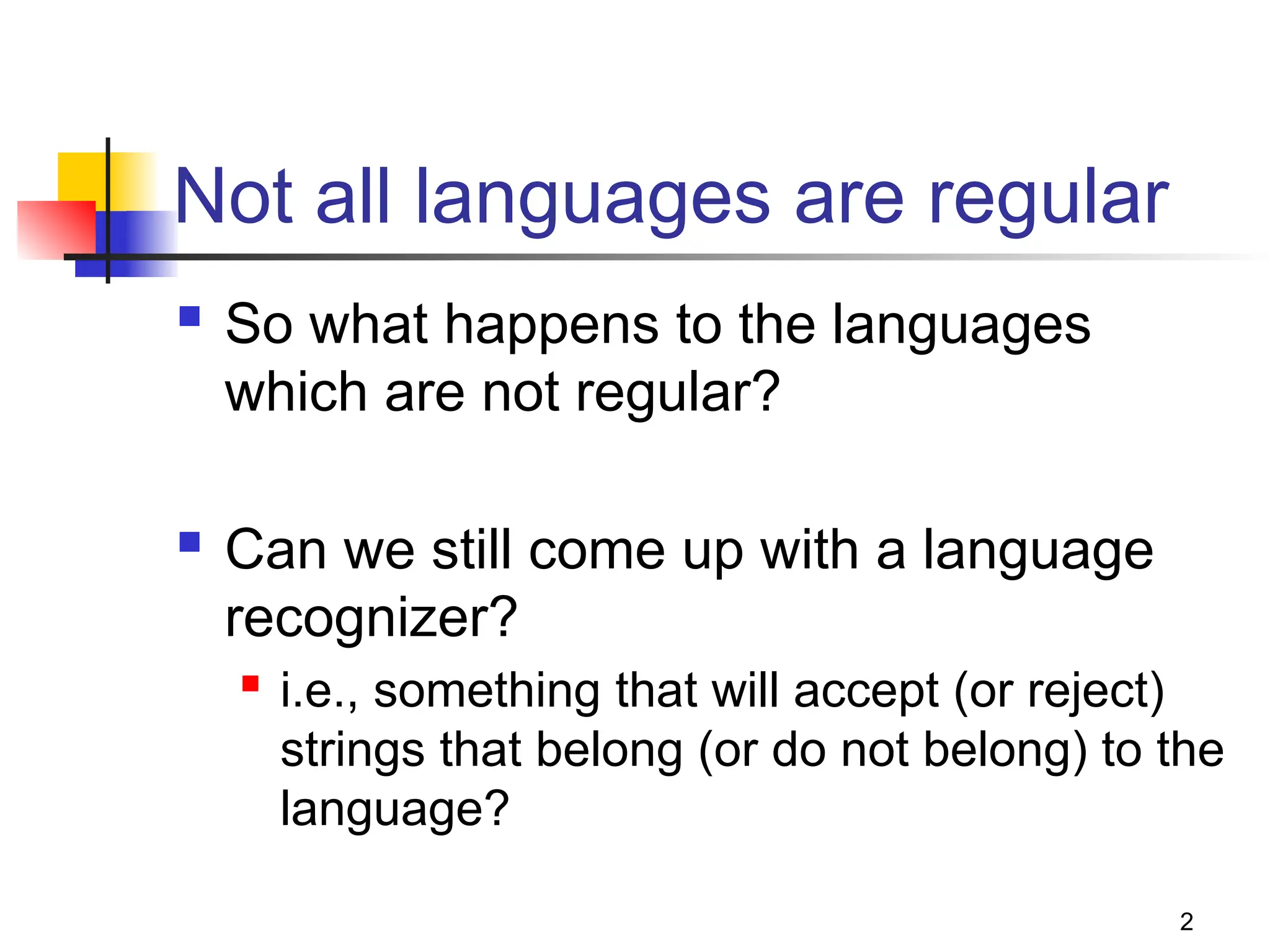

![18

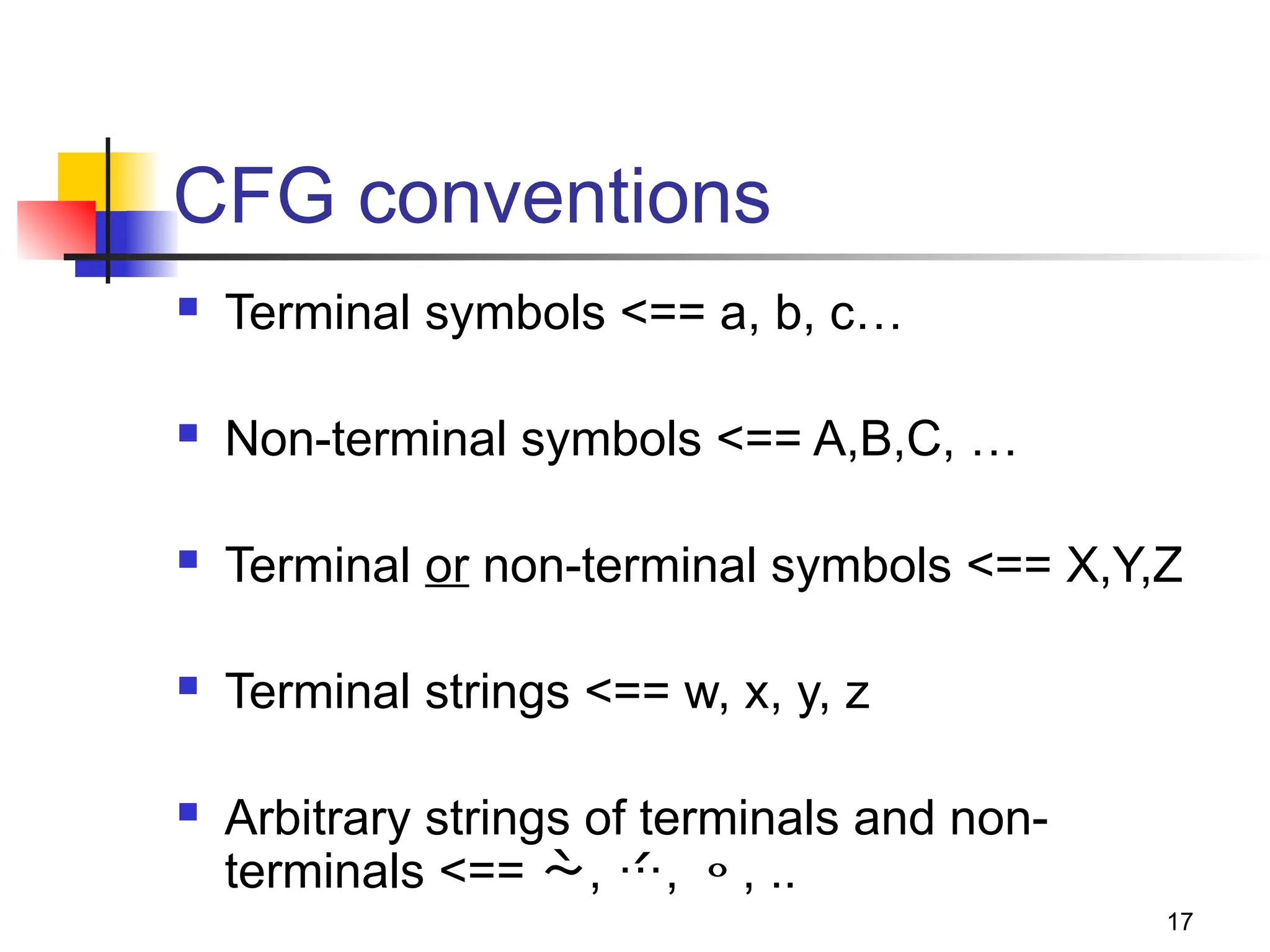

Syntactic Expressions in

Programming Languages

result = a*b + score + 10 * distance + c

Regular languages have only terminals

Reg expression = [a-z][a-z0-1]*

If we allow only letters a & b, and 0 & 1 for

constants (for simplification)

Regular expression = (a+b)(a+b+0+1)*

terminals variables Operators are also

terminals](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/automata6chapter5-240811032610-2d2cf8b4/75/AUTOMATA-AUTOMATA-AUTOMATA-Automata6Chapter5-pptx-18-2048.jpg)