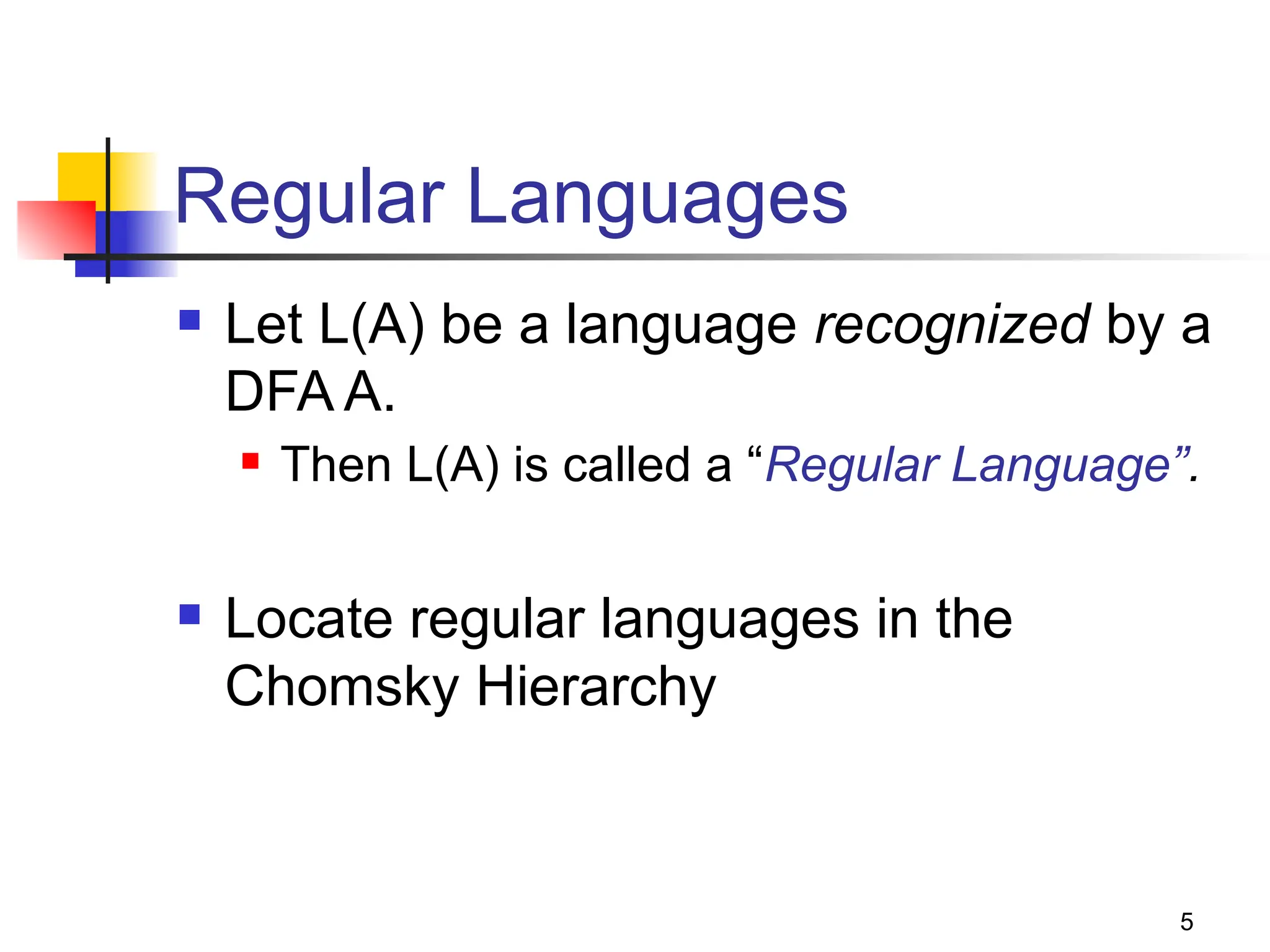

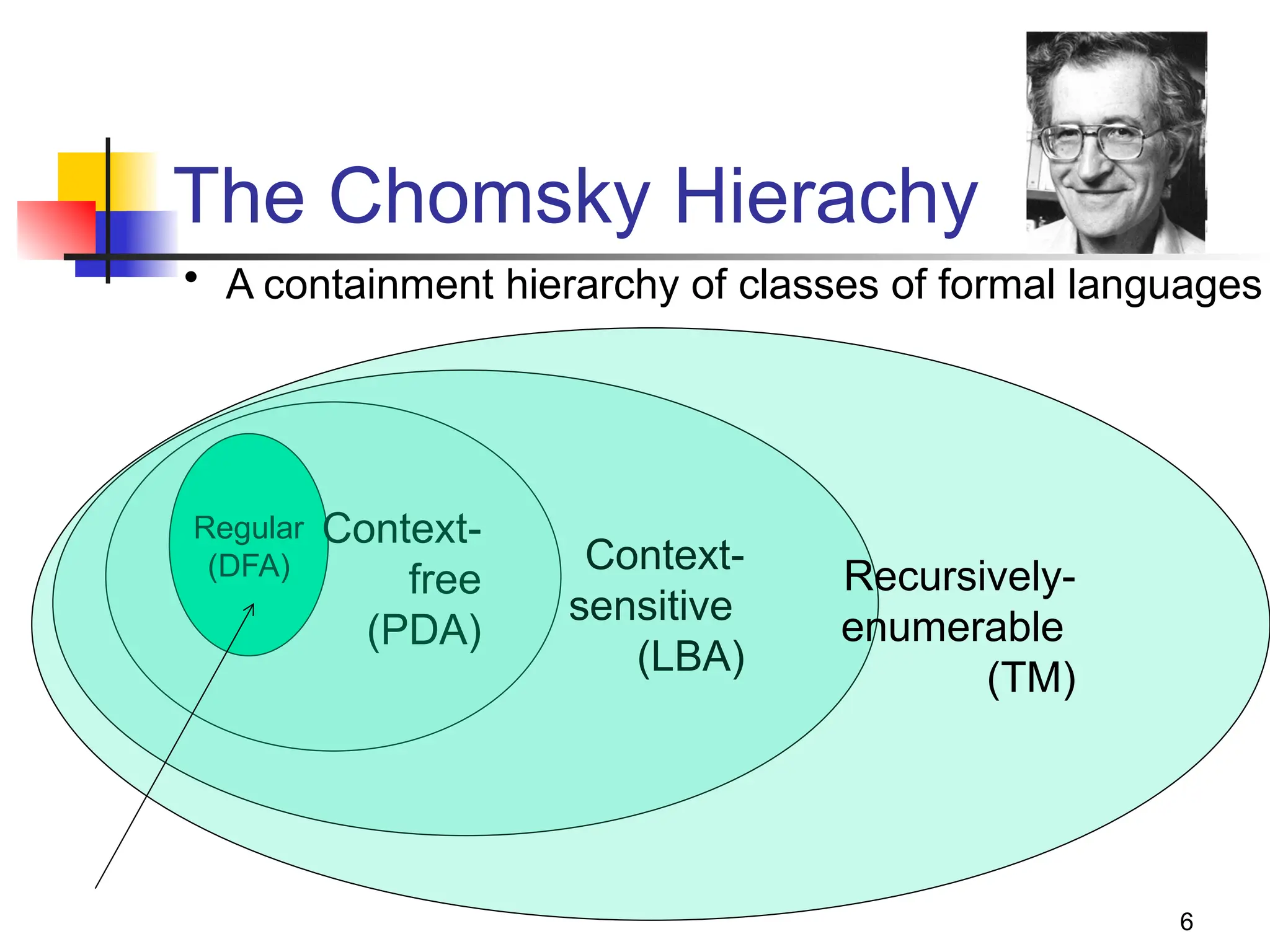

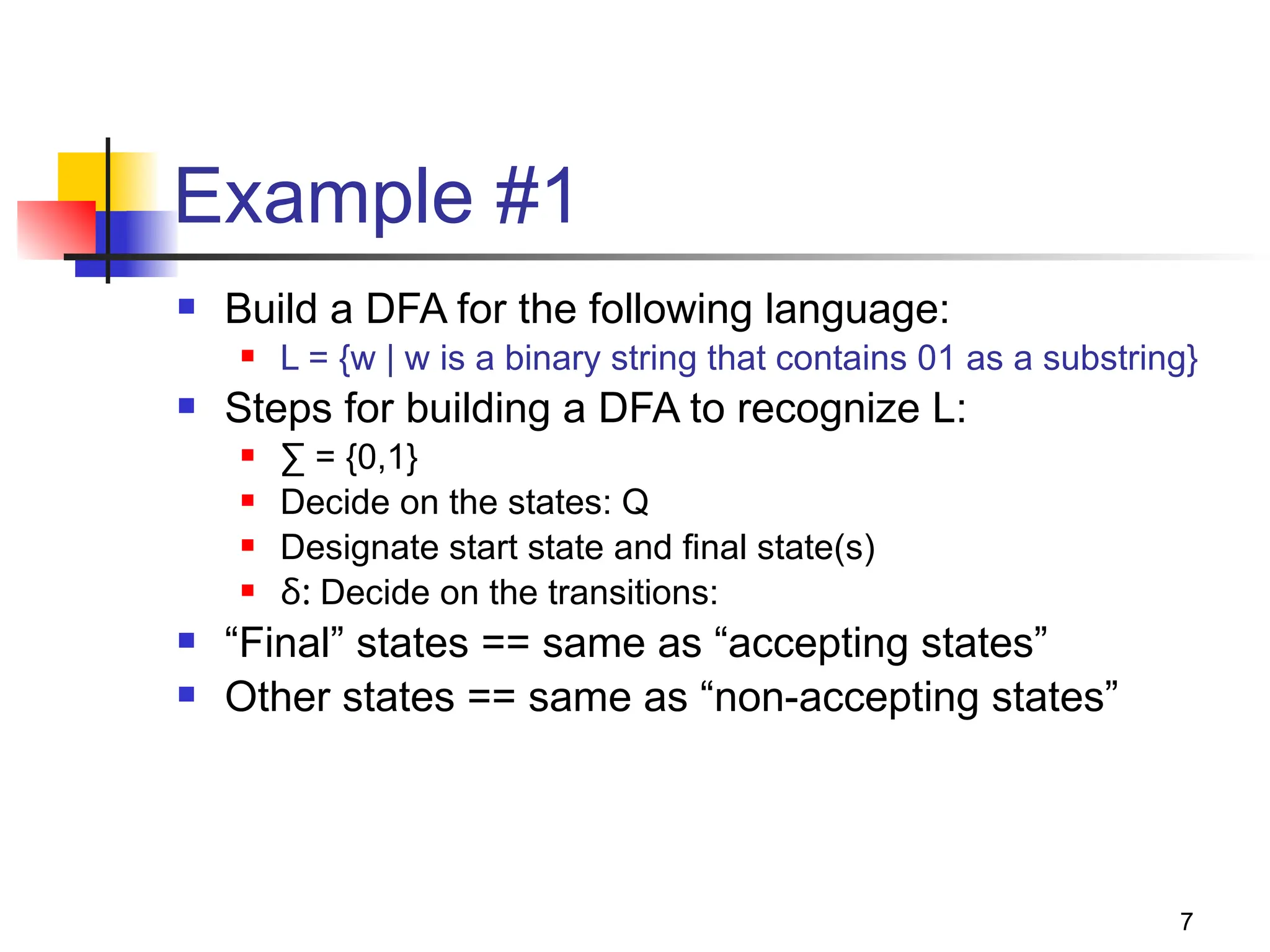

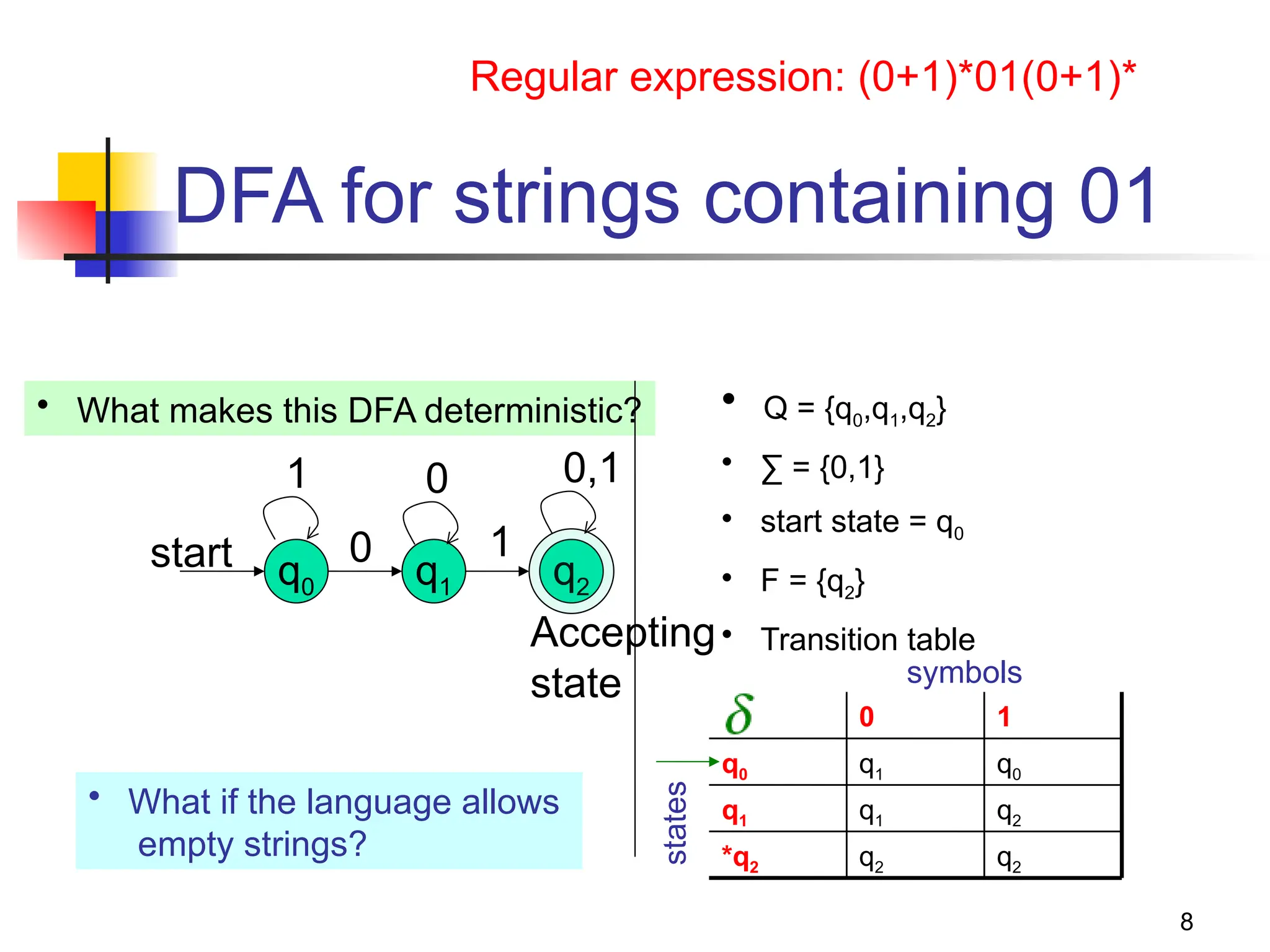

The document provides an overview of finite automata, including deterministic finite automata (DFA) and non-deterministic finite automata (NFA), highlighting their definitions, structures, and functionalities. It elaborates on the theoretical underpinnings of regular languages, Chomsky hierarchy, and includes examples of constructing DFAs and NFAs for various languages. The document also discusses the equivalences between DFAs and NFAs, the concept of epsilon-transitions, and practical applications of these automata in text processing and pattern recognition.

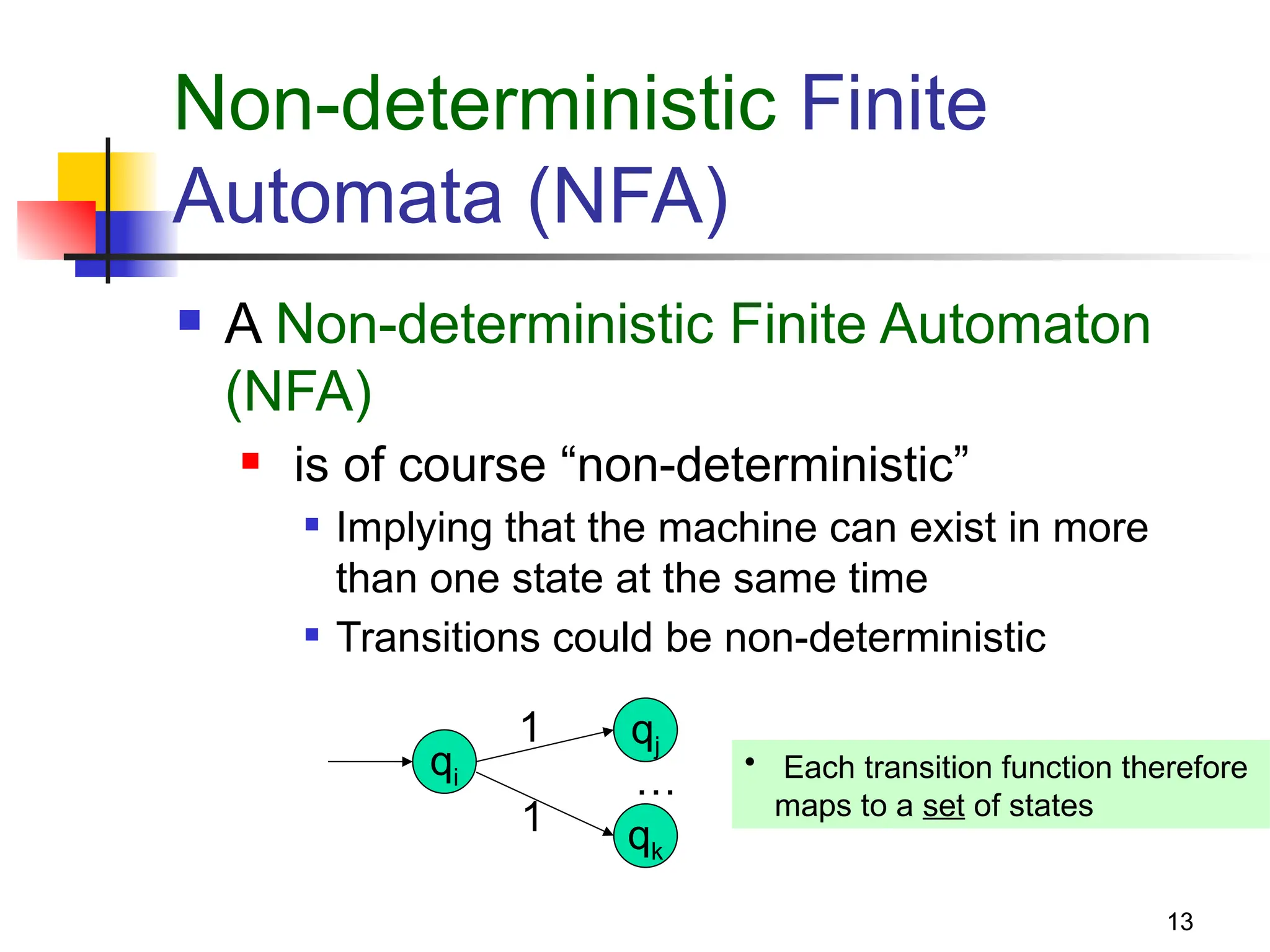

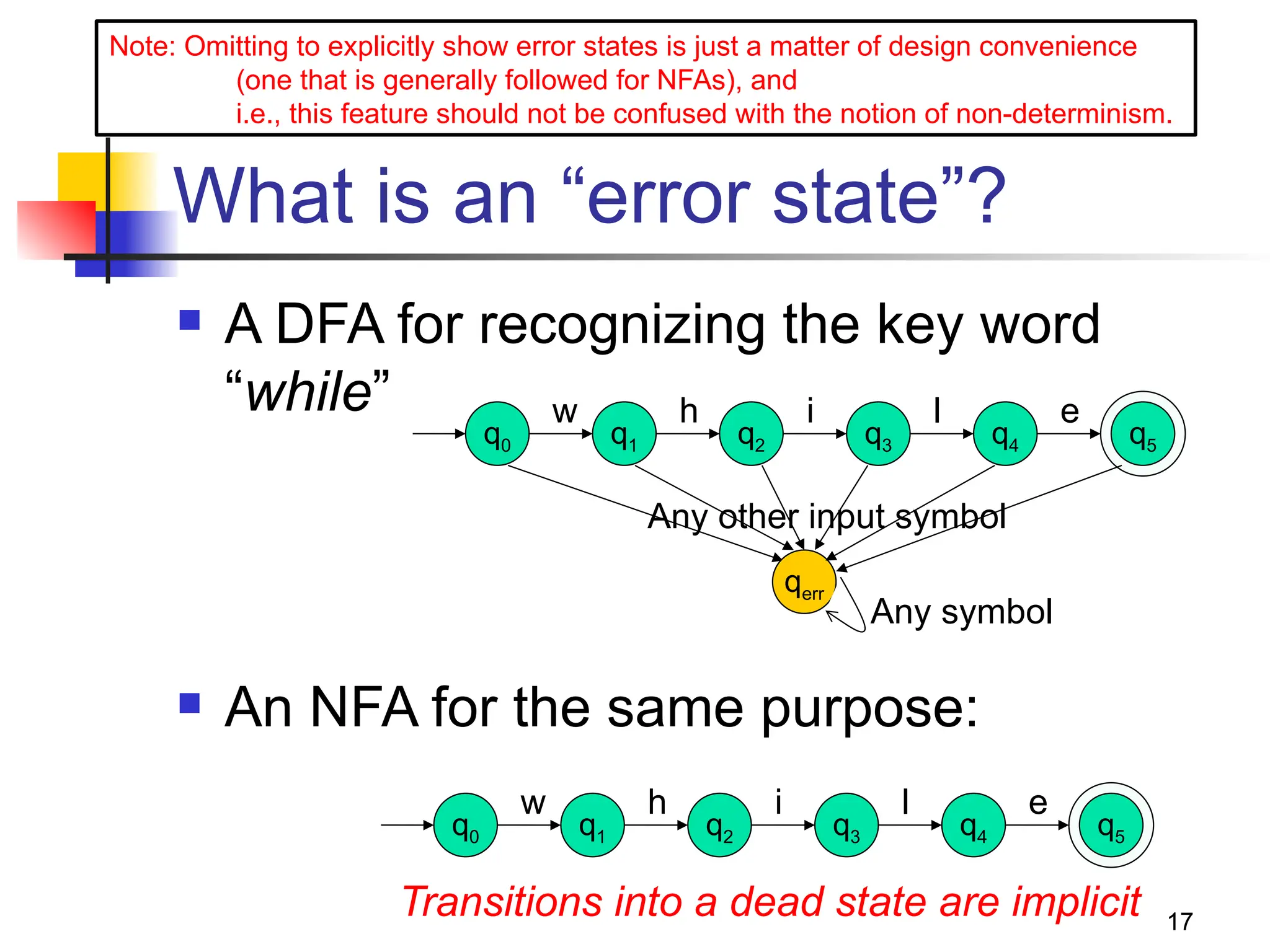

![27

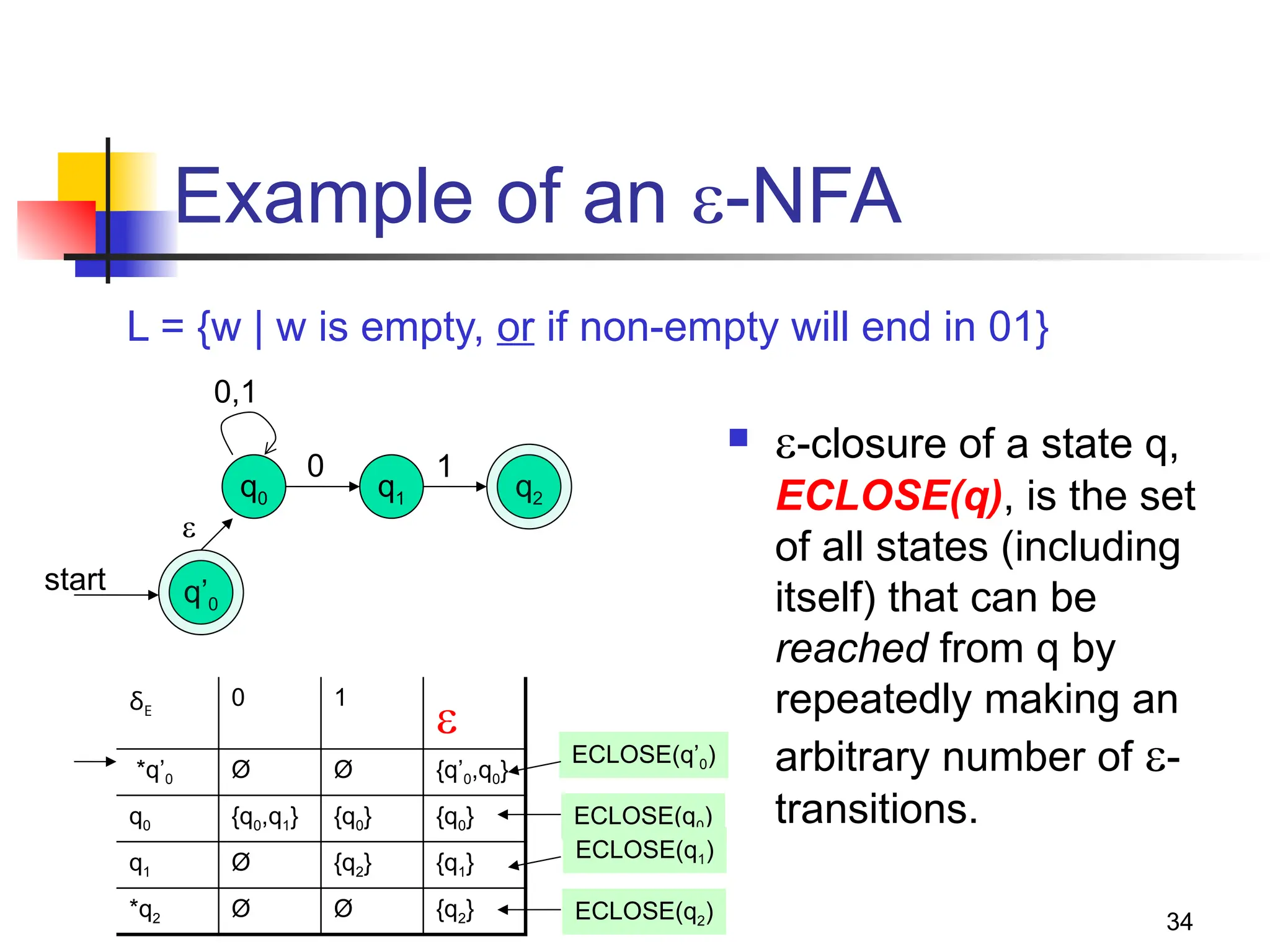

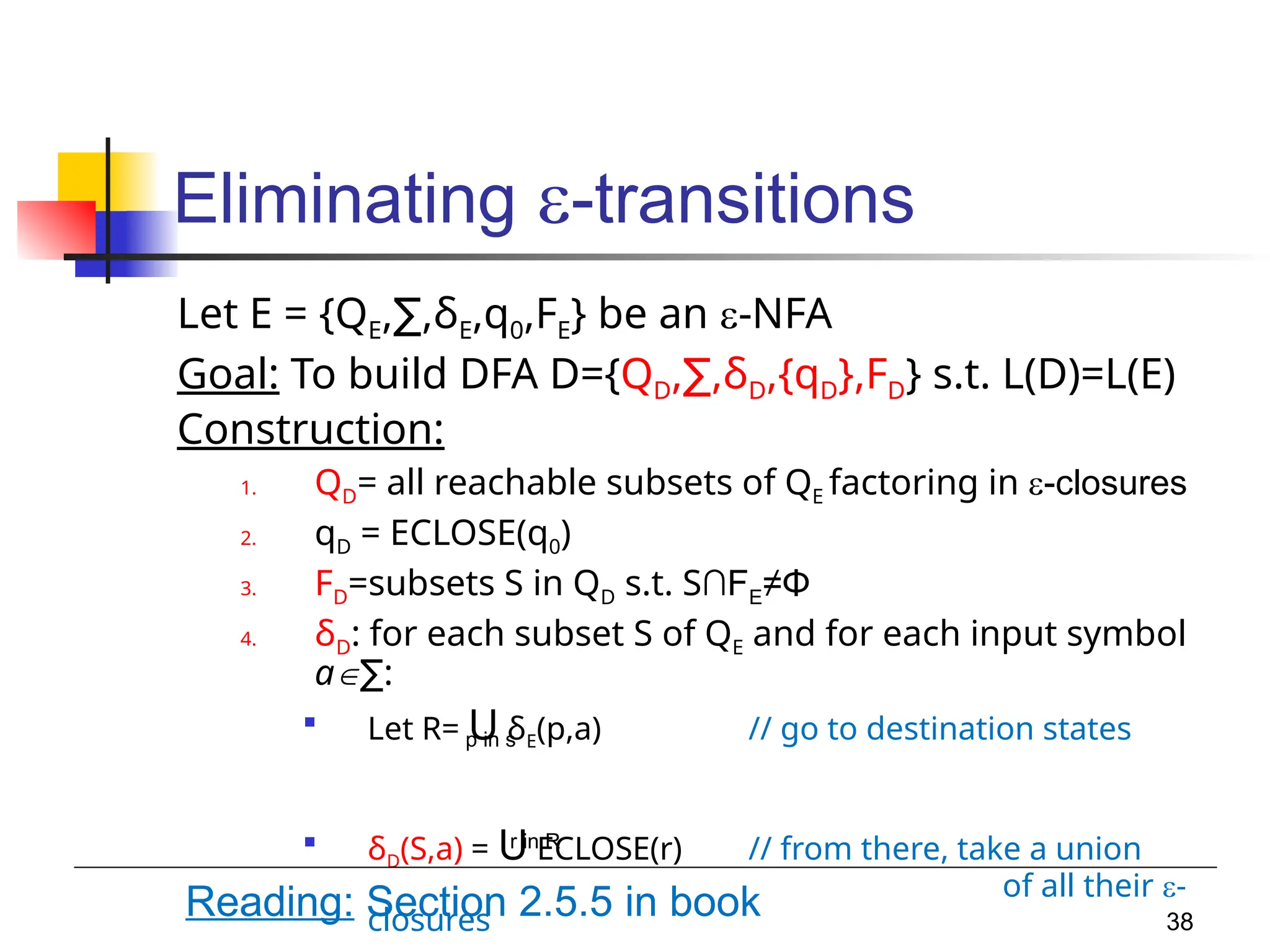

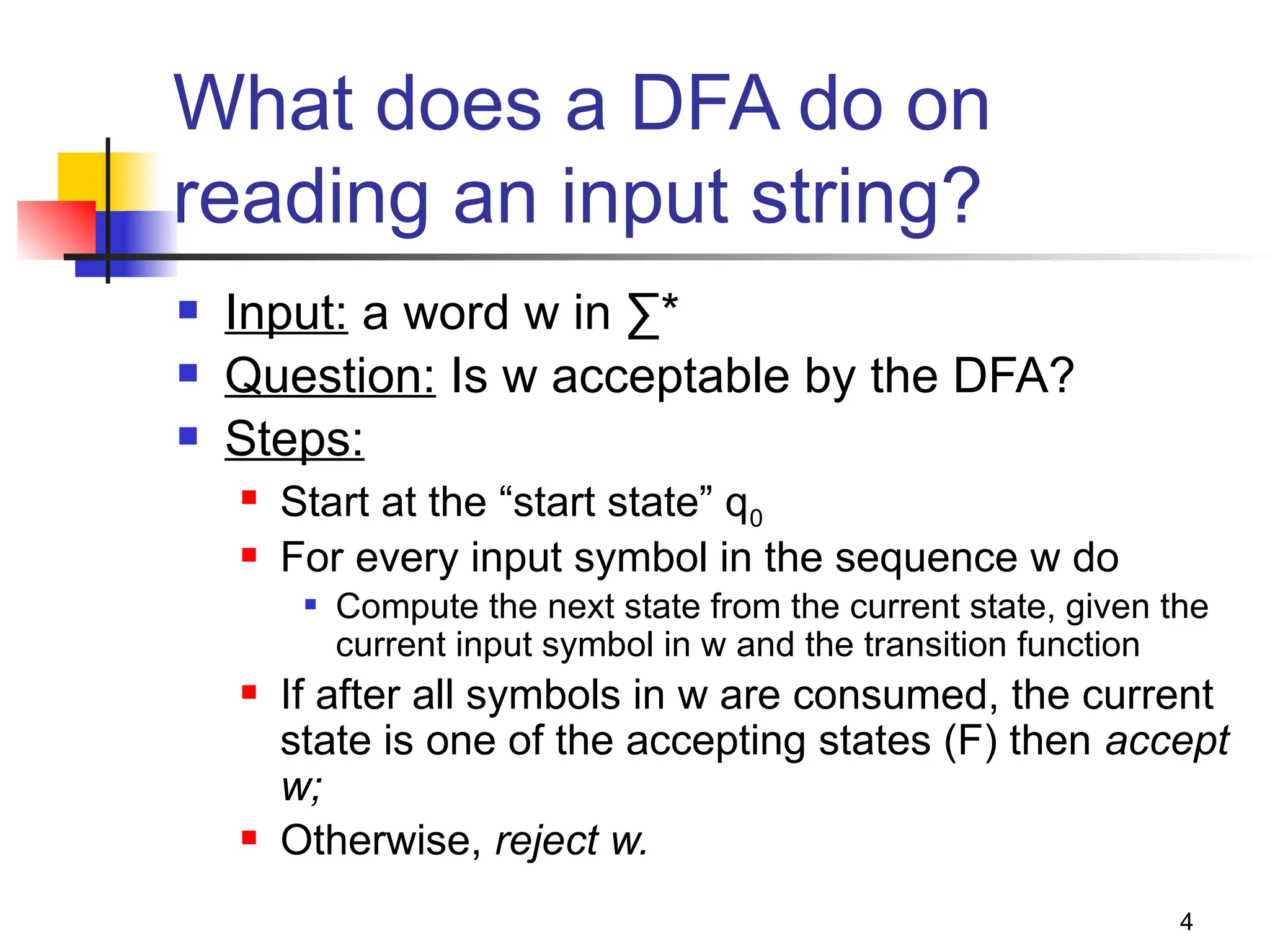

NFA to DFA construction: Example

L = {w | w ends in 01}

q0 q1

0

0,1

q2

1

NFA:

δN

0 1

q0 {q0,q1} {q0}

q1 Ø {q2}

*q2 Ø Ø

DFA:

δD

0 1

Ø Ø Ø

[q0] {q0,q1} {q0}

[q1] Ø {q2}

*[q2] Ø Ø

[q0,q1] {q0,q1} {q0,q2}

*[q0,q2] {q0,q1} {q0}

*[q1,q2] Ø {q2}

*[q0,q1,q2] {q0,q1} {q0,q2}

1. Determine transitions

δD

0 1

[q0] [q0,q1] [q0]

[q0,q1] [q0,q1] [q0,q2]

*[q0,q2] [q0,q1] [q0]

[q0]

1

0

[q0,q1]

1

[q0,q2]

0

0

1

Idea: To avoid enumerating all of

power set, do

“lazy creation of states”

2. Retain only those states

reachable from {q0}

0. Enumerate all possible subsets](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/automata3chapter2-240811031357-00bada55/75/AUTOMATA-THEORY-AUTOMATA-THEORYAutomata3Chapter2-pptx-27-2048.jpg)

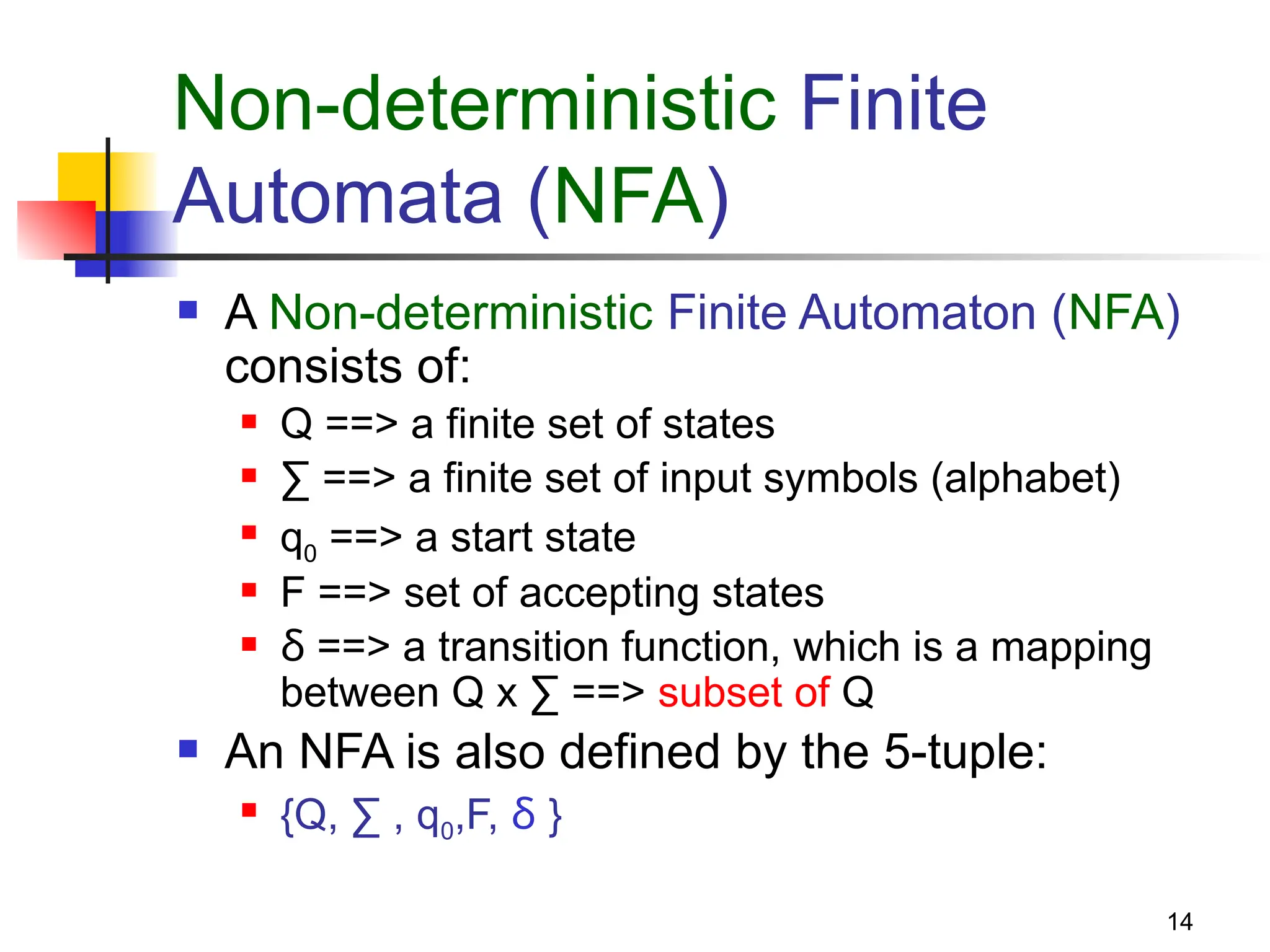

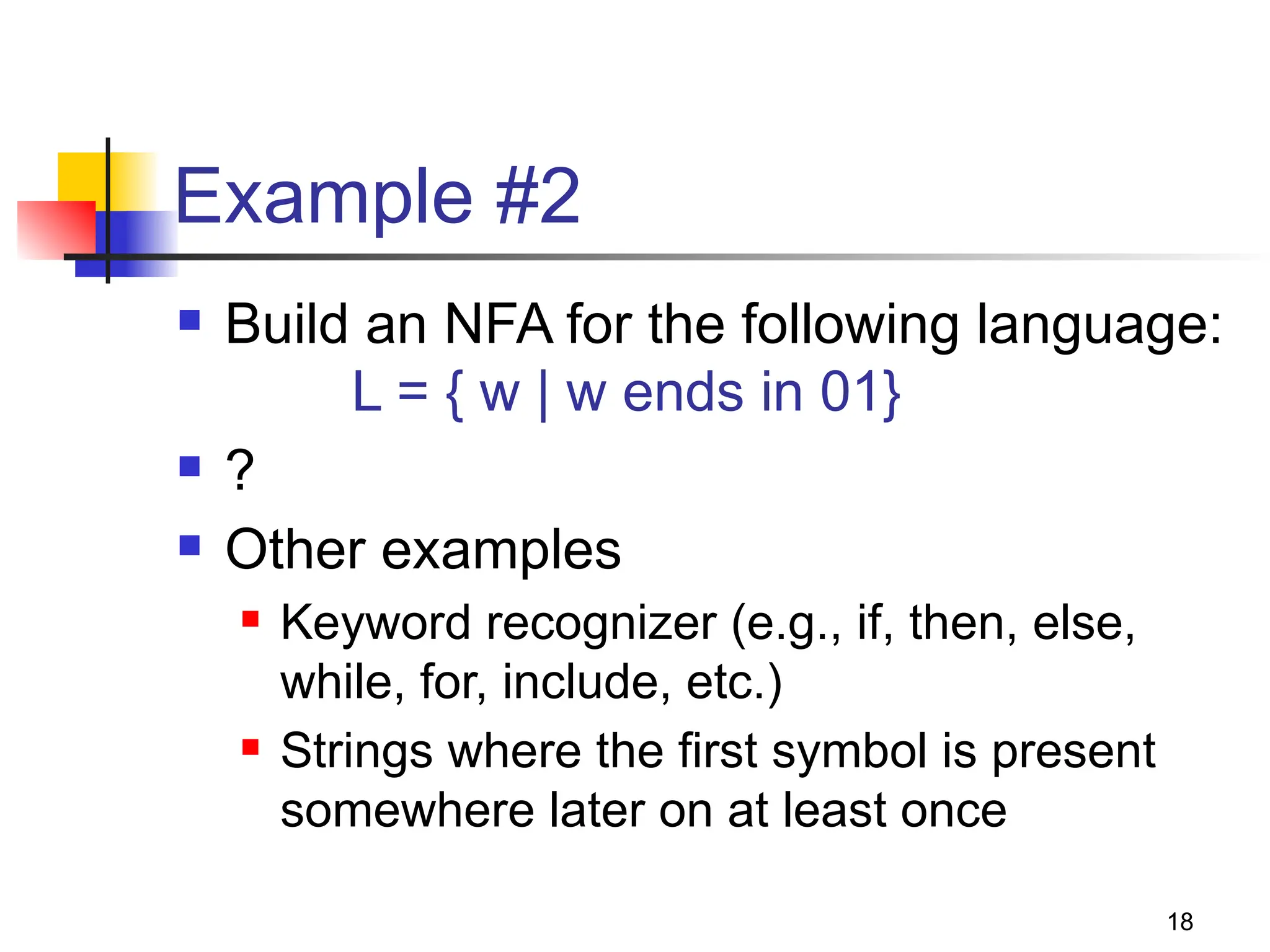

![28

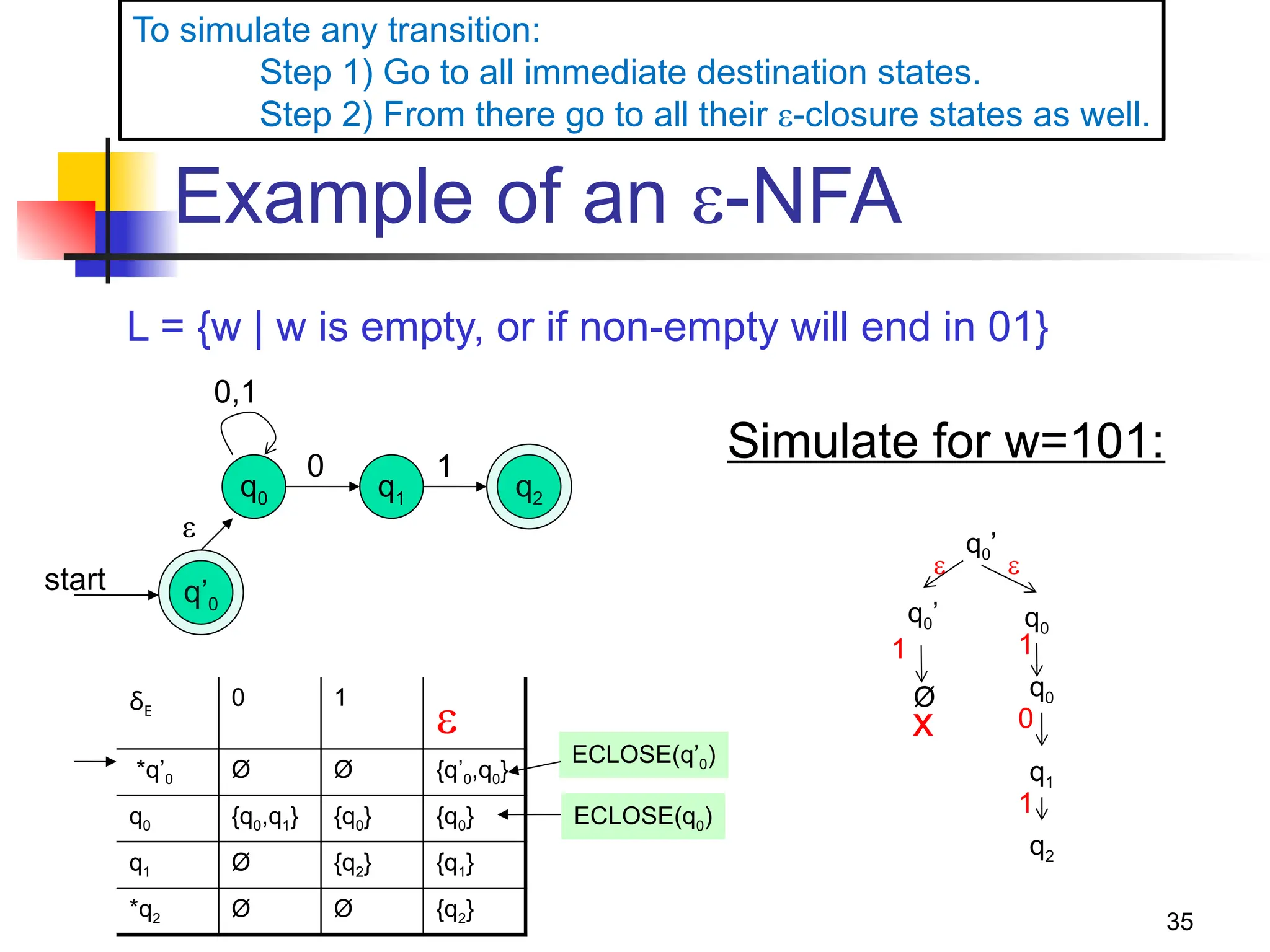

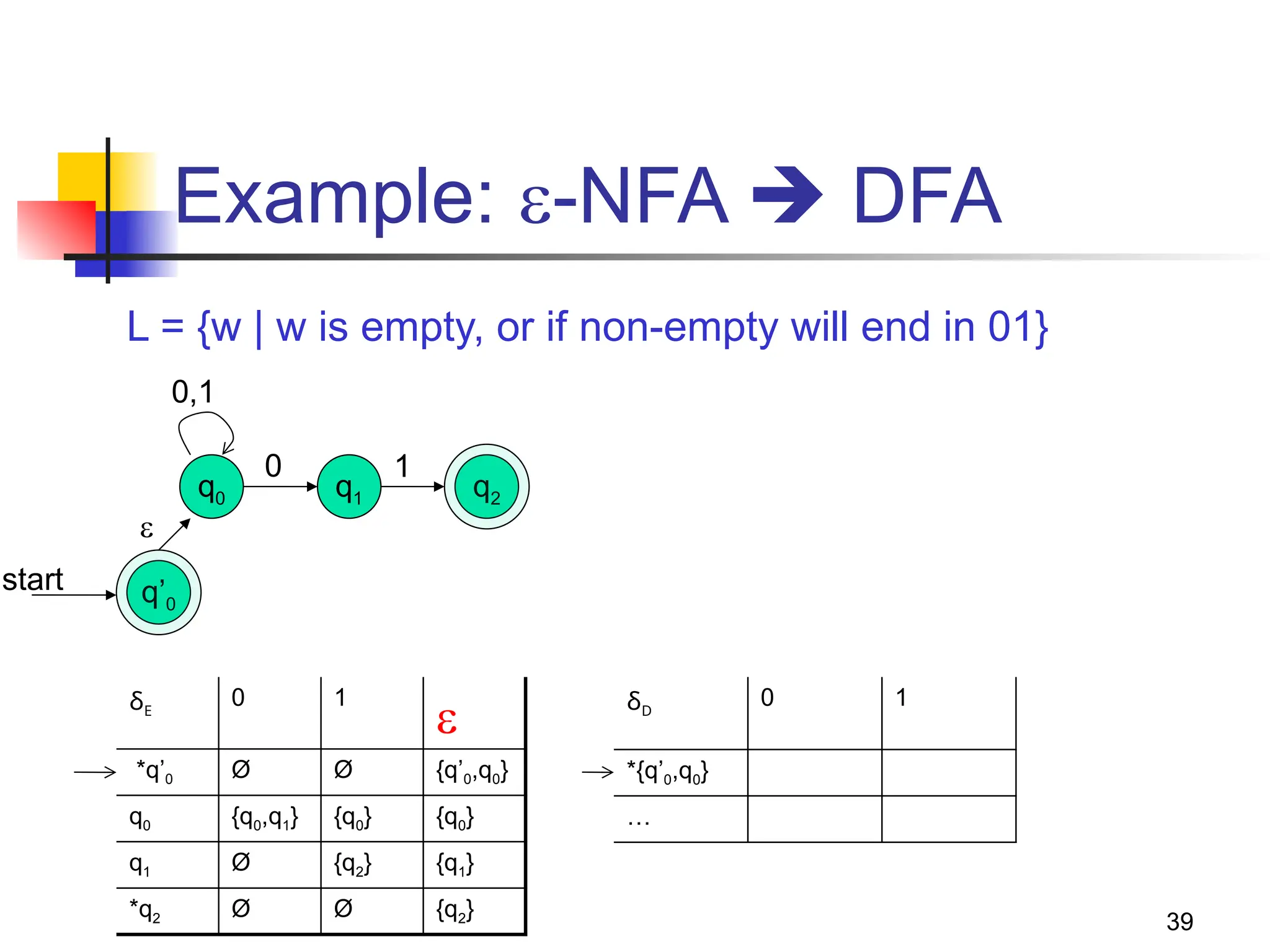

NFA to DFA: Repeating the example

using LAZY CREATION

L = {w | w ends in 01}

q0 q1

0

0,1

q2

1

NFA:

δN

0 1

q0 {q0,q1} {q0}

q1 Ø {q2}

*q2 Ø Ø

DFA:

δD

0 1

[q0] [q0,q1] [q0]

[q0,q1] [q0,q1] [q0,q2]

*[q0,q2] [q0,q1] [q0]

[q0]

1

0

[q0,q1]

1

[q0,q2]

0

0

1

Main Idea:

Introduce states as you go

(on a need basis)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/automata3chapter2-240811031357-00bada55/75/AUTOMATA-THEORY-AUTOMATA-THEORYAutomata3Chapter2-pptx-28-2048.jpg)