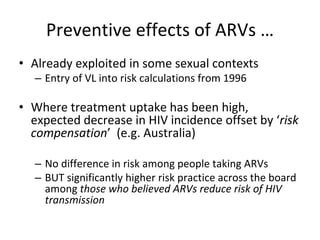

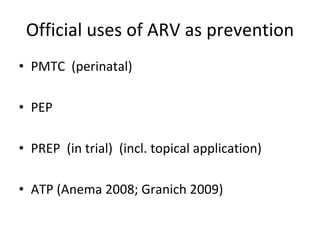

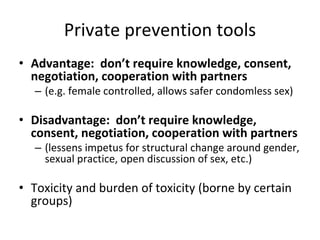

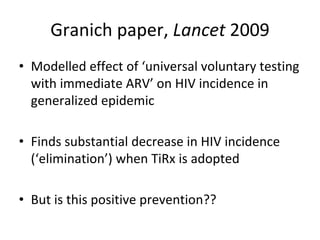

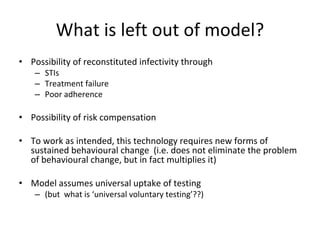

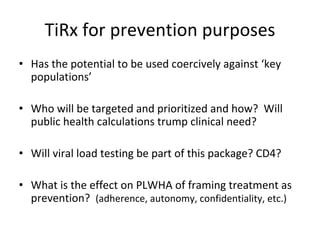

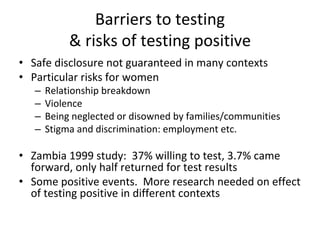

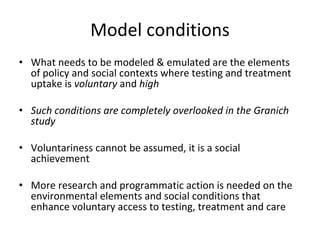

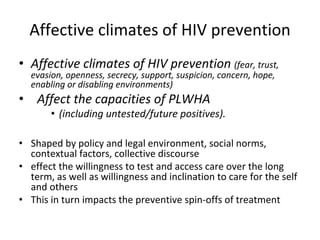

This document discusses the use of antiretroviral (ARV) drugs for HIV prevention, known as treatment as prevention (TasP). It notes that while TasP has benefits, its effects depend on how ARVs are implemented and taken up in different contexts. Concerns include risk compensation, lack of informed consent between partners, and prioritizing population health over individual clinical need. The document also questions assumptions in models showing TasP can eliminate HIV, as barriers to testing, relationship challenges, and sustainability over long term are not fully considered. Overall, it argues more research is needed on social factors that encourage voluntary and informed access to HIV prevention, testing and treatment.