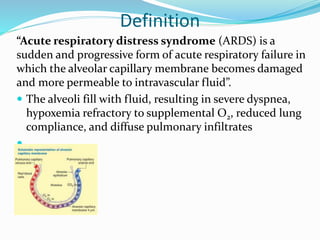

The document provides information on acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), including its definition, etiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, complications, diagnostic findings, and collaborative therapy. ARDS is defined as acute respiratory failure caused by damage to the alveolar-capillary membrane, resulting in fluid-filled alveoli. It has three pathophysiology phases: injury/exudative, reparative/proliferative, and fibrotic. Clinical features include hypoxemia, reduced lung compliance, and diffuse pulmonary infiltrates on chest imaging. Treatment involves mechanical ventilation with low tidal volumes, application of PEEP, and prone positioning to improve oxygenation.

![ Physiologic Stress Ulcers.

Critically ill patients with acute respiratory failure are at

high risk for stress ulcers.

Bleeding from stress ulcers occurs in 30% of patients

with ARDS who require PPV, a higher incidence than

other causes of acute respiratory failure.

Management strategies include correction of

predisposing conditions such as hypotension, shock, and

acidosis.

Prophylactic management includes antiulcer agents

such as H2-histamine receptor antagonists (e.g.,

ranitidine [Zantac]), as well as proton pump inhibitors

(e.g., pantoprazole [Protonix]) and mucosal-protecting

agents (e.g., sucralfate [Carafate]).

Early initiation of enteral nutrition also helps prevent

mucosal damage](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ards-230220035206-3eb572a7/85/ARDS-pptx-27-320.jpg)