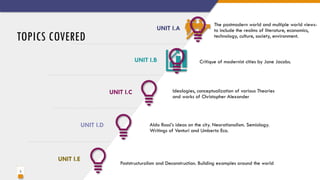

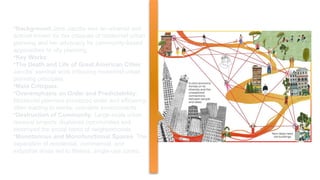

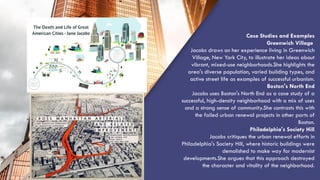

This document focuses on contemporary architecture and postmodern theories, examining significant topics such as critiques of modernism, the works of influential theorists like Jane Jacobs, and the implications of postmodern thought on urban planning. It covers key themes in postmodern literature, economics, culture, society, and technology, emphasizing ideas like cultural pluralism and the interconnectedness of systems. Jacobs’ critiques of modernist urban planning highlight the importance of mixed-use developments and community engagement for vibrant cities.