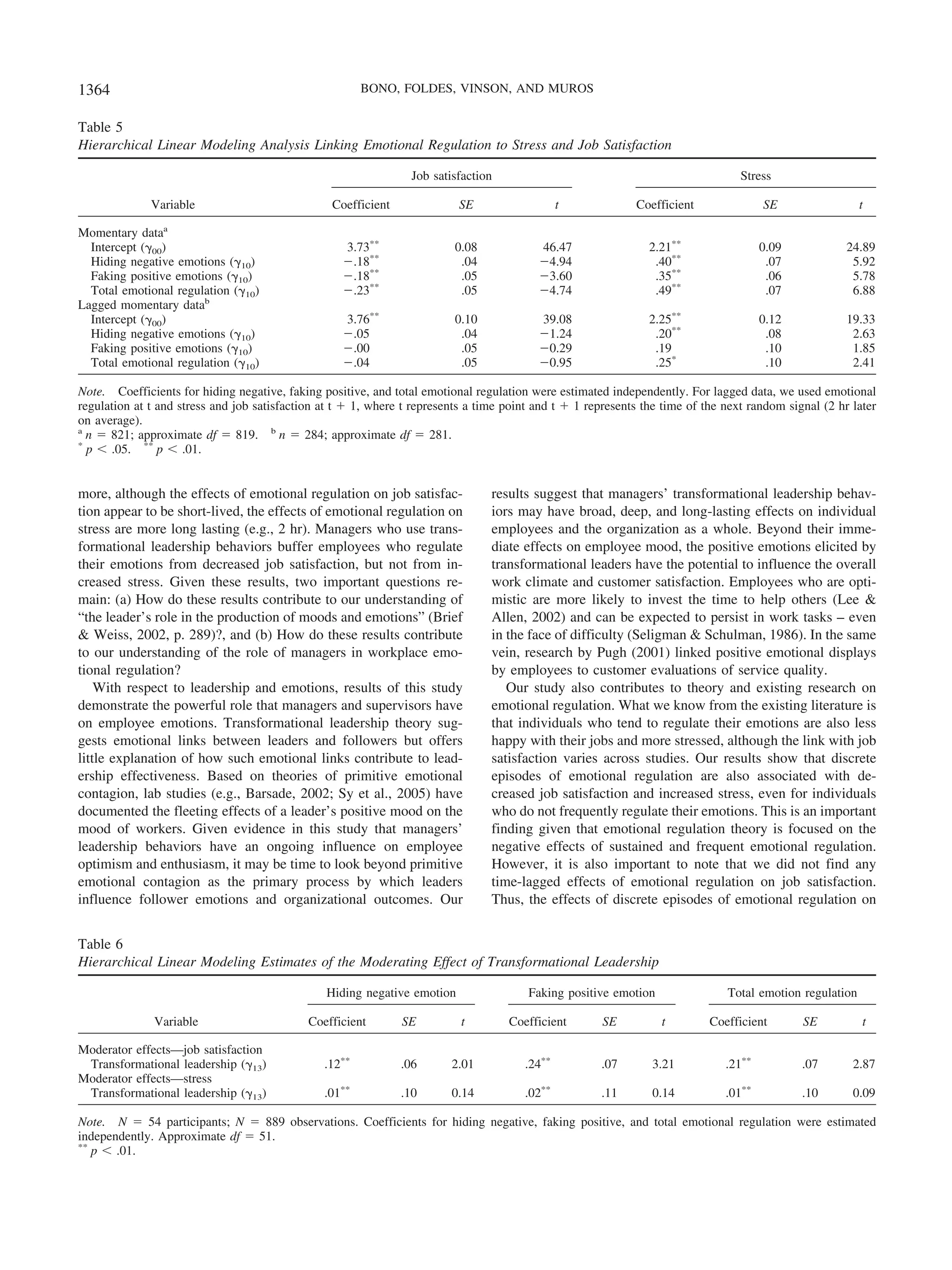

This study examined the role of organizational leaders in employees' emotional experiences. Data were collected from healthcare workers through experience sampling over 2 weeks. The results showed that:

1) Employees experienced fewer positive emotions and more negative emotions when interacting with supervisors compared to coworkers and customers.

2) Employees with supervisors high in transformational leadership experienced more positive emotions throughout the workday, including with coworkers and customers.

3) Employees who regulated their emotions experienced decreased job satisfaction and increased stress, but those with transformational leaders were less likely to be negatively impacted.

![(2002; Judge & Ilies, 2004) have found considerable variation in

job satisfaction over the course of the workday, which our mo-

mentary measure was designed to capture. We also obtained a

measure of general job satisfaction, using five Brayfield–Rothe

items (e.g., “Most days I am enthusiastic about my work”; see

Bono & Judge, 2003; Brayfield & Rothe, 1951). Responses for

these five items were on the same 5-point scale used for momen-

tary job satisfaction.

Work status and interactions. Immediately after being sig-

naled by the PDA, participants were asked to report whether they

were currently at work (yes or no). Next, they responded to the

following question: “When the beep went off, were you interacting

with any of the following?” 1 (supervisor), 2 (coworker), 3 (cus-

tomer/client), 4 (family/friends), 5 (no one), 6 (other).

Affective experiences. Although many taxonomies of affect

and emotion exist in the literature, we were constrained by our

method (i.e., surveys of only 1–2 min in length) to select a small

number of affect terms in attempting to cover the full range of

work-relevant affect and emotion. After reviewing the literature

(Ortony & Turner, 1990; Russell & Feldman Barrett, 1999;

Shaver, Schwartz, Kirson, & O’Connor, 1987) and conducting a

pilot study of workers who reported how frequently they expressed

each of 10 emotions at work, we selected three positive (happiness,

enthusiasm, and optimism) and three negative (anxiety, anger, and

irritation) work-relevant emotions. We excluded some basic emo-

tions (e.g., fear and love) and low-activation affect terms (e.g.,

contentment and calm), deeming them of low relevance to our

study. Participants reported the degree to which they felt the six

selected emotions at each signal.

Because Glomb and Tews (2004) illustrated the importance of

distinguishing between felt emotions and the act of emotional

regulation, we also asked participants about faking (i.e., expressing

an emotion they did not feel) the three positive emotions (happi-

ness, enthusiasm, and optimism) and hiding (i.e., feeling an emo-

tion they were not expressing) the three negative emotions (anxi-

ety, irritation, and anger). Responses for these items were

evaluated on a 7-point scale (1 ϭ none at all, 7 ϭ an intense

amount) for feeling, hiding, and faking.

Stress. We assessed momentary stress by asking participants

to respond to the statement “At this very moment, I am experi-

encing stress.” This measure was intended to capture variability in

stress throughout the day. We also obtained an overall, global

measure of stress, using Motowidlo, Packard, and Manning’s

(1986) four-item measure. Responses for both momentary and

overall stress items were on the same 5-point scale used for job

satisfaction.

Data Analyses

Prior to conducting our analyses of interest, we examined sev-

eral properties of our data. We excluded data from 3 participants

who had responded to fewer than three signals over the course of

the 2 weeks (1 because of job termination, 1 because of PDA

failure, and 1 for an unknown reason). Therefore, the total possible

number of responses was approximately 2,160 (4 responses per

day ϫ 10 workdays ϫ 54 participants ϭ 2,160); however, because

of scheduling the drop-off and pick-up of PDAs, a few participants

responded to surveys on Days 11 and 12, raising the total possible

to 2,266). Participants responded to 1,983 signals (approximately

88% of the total possible), with an average of 37 responses per

participant (ranging from 11 to 42). We excluded data from re-

sponses when participants were not at work (n ϭ 287 episodes)

and for interactions with family or friends (n ϭ 52 episodes),

resulting in 1,653 work-related responses. Our goal was to exam-

ine emotional regulation in a social context. However, in many

cases participants were alone when the signal sounded (n ϭ 764;

48% of work-related responses).4

Thus, our final data set consisted

of 889 responses (52% of total at-work responses; average of 15

per participant) from employees who were at work and involved in

a work-related interaction at the time of the signal.

To form a single leadership score for the supervisor of each

participant, we aggregated the leadership survey responses of all

employees who completed a survey for the target supervisor (av-

erage n ϭ 5 reports per supervisor). Aggregating leadership reports

across followers was deemed justifiable in these data by a signif-

icant ICC-1 value of .29 (p Ͻ .01) and an ICC-2 value of .72. The

ICC-2 value can be interpreted as the reliability of the aggregated

measure of leadership. An average rwg ϭ .84 across groups

(James, Demaree, & Wolf, 1984; assuming a slight negative skew

in the data [Bono & Judge, 2003]) further supports aggregation.

We also created several composite emotion variables. The three

positive (enthusiasm, happiness, and optimism) and three negative

(anger, irritation, and anxiety) emotions were highly correlated

within individuals for both felt emotions and emotional regulation

(average r ϭ .87, .77, .93, and .82, for positive experienced,

negative experienced, positive faked, and negative hidden, respec-

tively). Therefore, we computed four composite emotion variables:

positive emotions experienced, negative emotions experienced,

positive emotions faked, and negative emotions hidden. Principal-

components analysis provided support for creating these compos-

ites, as we found that a single factor explained most of the variance

(ranging from 70%–82%) in each set of related emotions. We also

found that the two types of emotional regulation were highly

related (i.e., faking positive emotions and hiding negative emo-

tions tended to co-occur; r ϭ .88, p Ͻ .01). Because we were

interested in possible differential effects of the two types of emo-

tional regulation, we included faking positive and hiding negative

in our analyses. However, we also formed a total emotional reg-

ulation score by averaging the two types of emotional regulation.

Our hypotheses address two levels of analysis. Within-subject

analyses must be used to link emotional regulation within an

individual with momentary variation in stress and job satisfaction

(Hypothesis 3). In these analyses, data from each individual are

centered around that individual’s mean score, effectively control-

ling for mean differences between individuals in emotional regu-

lation, job satisfaction, and stress. Cross-level (between- and

within-subjects) analyses are used to test our leadership hypothe-

ses (Hypotheses 1, 2, and 4), which posit associations between

supervisory behavior and employees’ emotional experiences.

Therefore, we analyzed our data using multilevel modeling tech-

niques (i.e., HLM 5; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002).

4

A comparison of affective experiences when interacting with others

versus alone revealed no significant differences in experienced positive and

negative emotions or in emotional regulation.

1361LEADERSHIP AND EMPLOYEE EMOTIONS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/apl9251357-pdfemotii-130516171431-phpapp01/75/Apl-92-5_1357-pdf-emotii-5-2048.jpg)

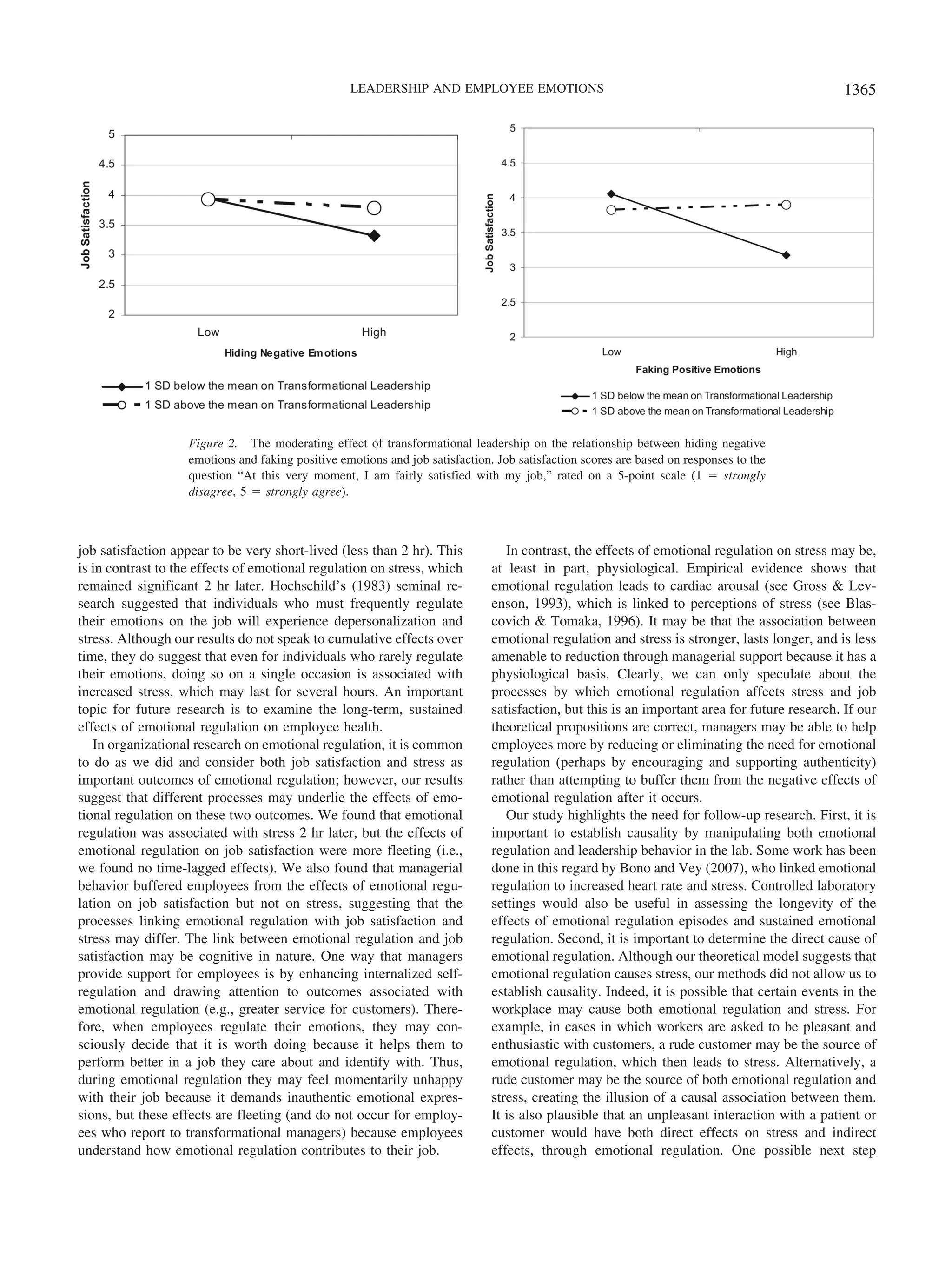

![significant effects for emotional regulation (t) on stress were found

after 4 hr (t ϩ 2), and sample sizes were too small to examine t ϩ

3 data (i.e., average 6-hr time lag). Although our data are corre-

lational and preclude firm causal conclusions, these results lend

support to our proposed causal ordering of the variables (e.g.,

emotional regulation 3 stress), as we also tested the reverse

ordering (e.g., stress [t] 3 emotional regulation [t ϩ 1]) and found

no significant effects. The effects of emotional regulation on job

satisfaction appear to be more fleeting than the effects of stress, as

emotional regulation did not predict job satisfaction after 2 hr.

Leadership as buffer. We suggested that leadership behaviors

would buffer employees from the negative effects of emotional

regulation. Results in Table 6 support Hypothesis 4a, revealing a

significant moderating effect for transformational leadership (␥ ϭ

.21, p Ͻ .01) on the association between emotional regulation and

job satisfaction. Figure 2 shows that when transformational lead-

ership behaviors were low (1 standard deviation below the mean),

episodes of emotional regulation were associated with decreased

job satisfaction. However, when transformational leadership be-

haviors were high (1 standard deviation above the mean), there

was little or no association between emotional regulation and job

satisfaction. A different picture emerged when we examined stress

(Hypothesis 4b). Contrary to our expectations, supervisors’ trans-

formational leadership behaviors did not protect employees from

the stress associated with emotional regulation (see Table 6).5

Discussion

According to Brief and Weiss (2002), “the organizational liter-

ature is populated with many more ideas about the leader’s role in

the production of moods and emotions than it is with relevant data”

(p. 289). In this study we focused on the role of managers in

producing employee emotions and in buffering them from the

effects of emotional regulation. With respect to the former, our

results revealed that employees experience less optimism, happi-

ness, and enthusiasm when they interact with supervisors than

when they interact with customers, clients, and coworkers. We also

found that employees who report to supervisors who engage in

transformational leadership behaviors, compared with those who

do not, experience more optimism, happiness, and enthusiasm

throughout the day, including during their interactions with cus-

tomers and coworkers. With respect to the latter, our results

indicate that when employees regulate their emotions at work, they

experience increased stress and decreased job satisfaction. Further-

5

Several participants in our sample reported to the same supervisor,

creating dependencies in the leadership data that were not addressed in our

hierarchical linear modeling analyses and may have potentially produced

biased tests of significance. Thus, we repeated our moderator analyses

involving leadership (see Table 6) using only 1 participant per leader. This

reduced our sample size (from 54 to 27) but eliminated the dependencies.

All significant effects reported in Table 6 remained significant in this

subsample.

Table 3

Analysis of Variance for Felt and Regulated Emotions by Interaction Partner

Emotion

Interaction

partner M SD F

% total variance explained

by interaction partner

Feel positive Supervisor 3.05 1.44 5.74**

36

Coworker 3.75 1.25

Customer-client 3.53 1.58

Other 3.54 1.47

Feel negative Supervisor 2.08 1.35 1.01 4

Coworker 1.83 1.13

Customer-client 1.90 1.14

Other 1.84 1.19

Fake positive Supervisor 1.38 0.91 0.30 6

Coworker 1.47 0.88

Customer-client 1.46 0.85

Other 1.42 0.86

Hide negative Supervisor 1.50 1.01 0.61 3

Coworker 1.62 1.04

Customer-client 1.67 1.05

Other 1.56 0.99

Note. N ϭ 889. dfs ϭ 3, 886. The frequency of interactions was as follows: coworker, 55%; customer-client,

23%; supervisor, 8%; other (which included groups of individuals), 14%.

**

p Ͻ .01.

Table 4

Hierarchical Linear Modeling Estimates of the Associations

Between Supervisors’ Leadership Behaviors and Participants’

Affective Experiences

Affective experiences

Transformational leadership behavior

(␥01)

Coefficient SE t

Feeling positive .54**

.18 2.94

Feeling negative .03 .22 0.15

Faking positive .11 .16 0.73

Hiding negative .18 .20 0.94

Total emotional regulation .14 .17 0.85

Note. N ϭ 54 participants; N ϭ 889 observations. Coefficients for feeling

positive, feeling negative, faking positive, hiding negative, and total emo-

tional regulation were estimated independently. Approximate df ϭ 51.

**

p Ͻ .01.

1363LEADERSHIP AND EMPLOYEE EMOTIONS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/apl9251357-pdfemotii-130516171431-phpapp01/75/Apl-92-5_1357-pdf-emotii-7-2048.jpg)