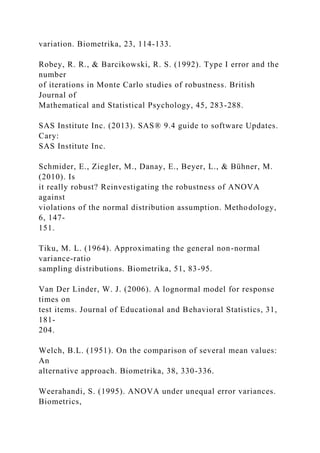

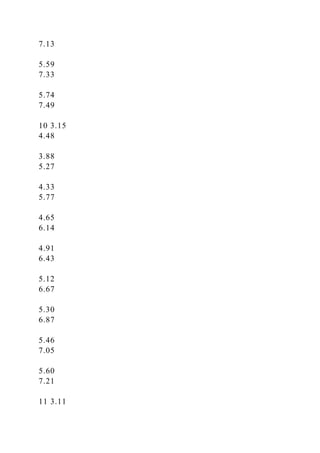

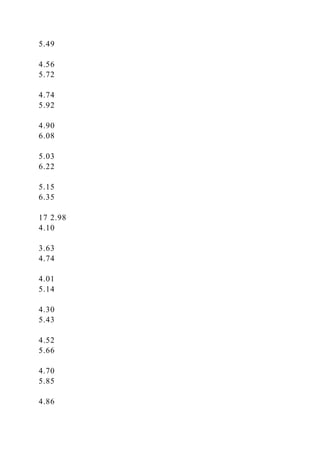

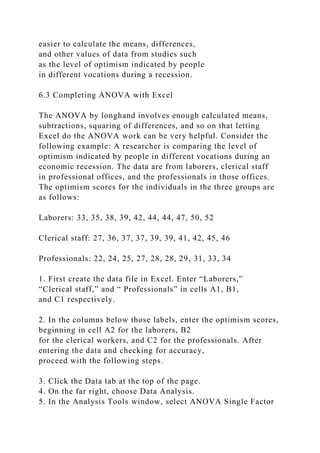

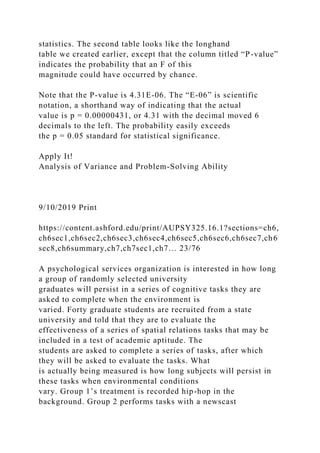

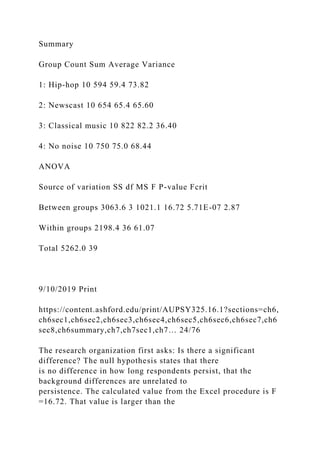

The document discusses the use of one-way ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) to compare the efficacy of three memory techniques: repetition, imagery, and mnemonics. It explains the rationale behind using ANOVA instead of multiple t-tests to analyze differences between groups, details the concept of error variance, and presents a case study involving a researcher analyzing participants' memorization scores. The content also outlines fundamental concepts related to ANOVA, such as hypothesis formulation, sum of squares, and the critical role of the F ratio in determining statistical significance.

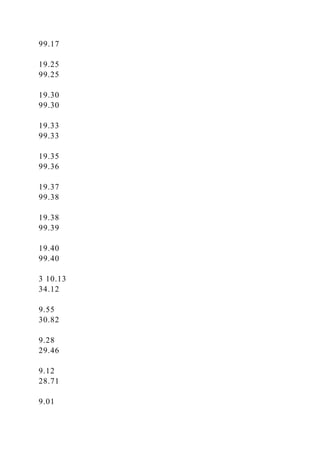

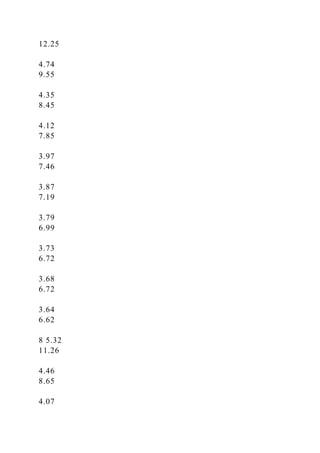

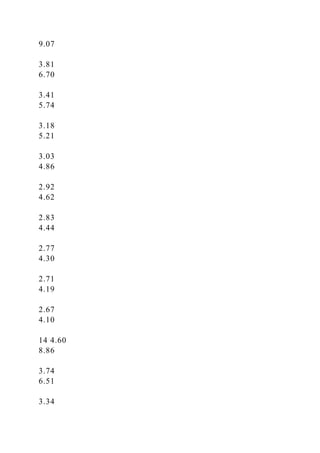

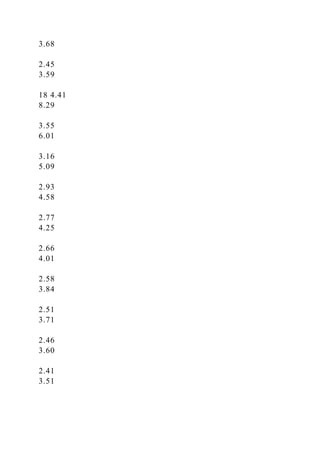

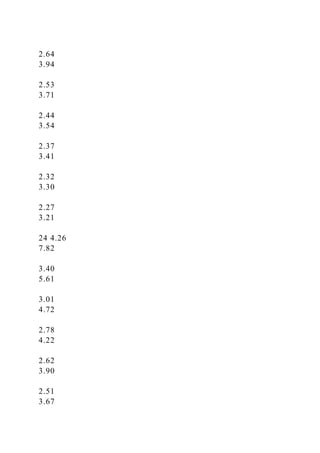

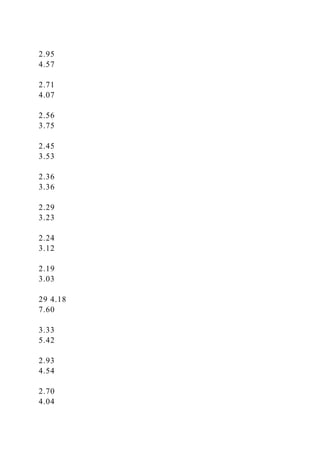

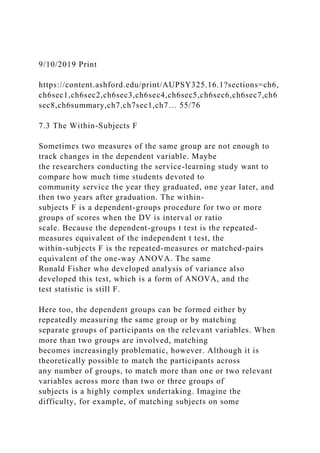

![the calculated F value compares to the

critical value from the table.

2. If the F is significant, which groups are significantly

different from each other? That question is

answered by a post hoc test such as Tukey’s HSD.

3. IfF is significant, how important is the result? The question

is answered by an effect-size calculation.

If F is not statistically significant, questions 2 and 3 are

nonissues.

After addressing the first two questions, we now turn our

attention to the

third question, effect size. With the t test in Chapter 5, omega-

squared

answered the question about how important the result was.

There are

similar measures for analysis of variance, and in fact, several

effect-size

statistics have been used to explain the importance of a

significant

ANOVA result. Omega-squared (ω2) and partial eta-squared

(η2) (where

the Greek letter eta [η] is pronounced like “ate a” as in “ate a

grape”) are

both quite common in social-science research literature. Both

effect-size

statistics are demonstrated here, the omega-squared to be

consistent with

Chapter 5, and—because it is easy to calculate and quite

common in the

literature—we will also demonstrate eta-squared. Both statistics

answer

the same question: Because some of the variance in scores is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/anovainterpretationset1studythisscenarioandanova-221014163318-bc8c28fa/85/ANOVA-Interpretation-Set-1-Study-this-scenario-and-ANOVA-docx-84-320.jpg)

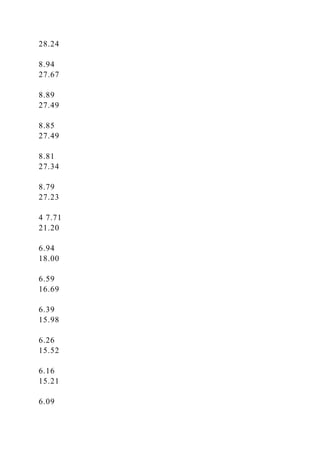

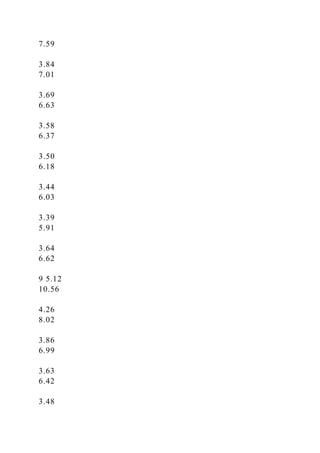

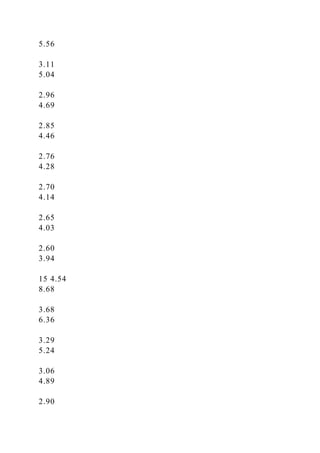

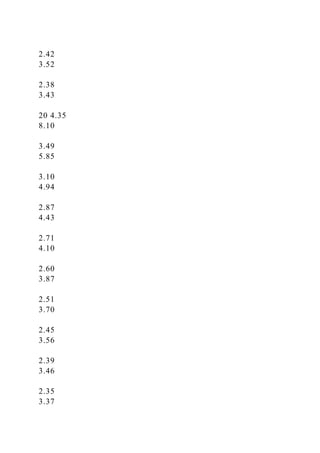

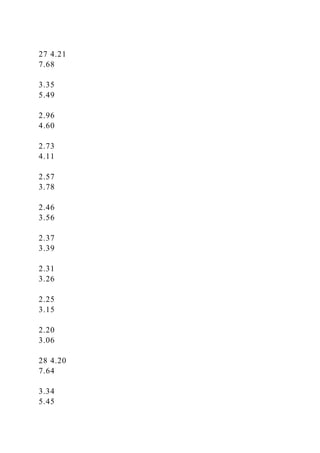

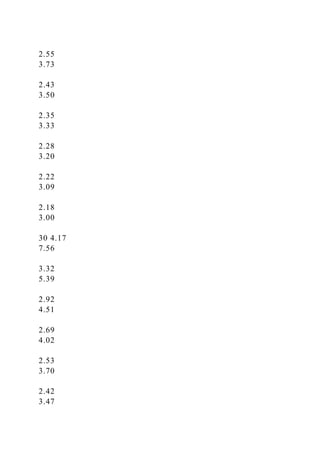

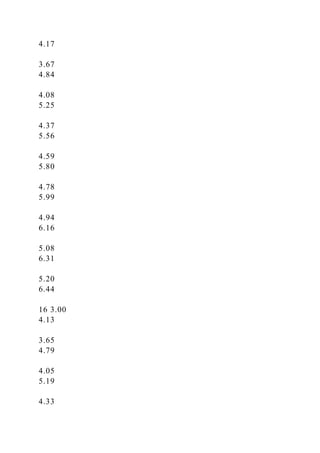

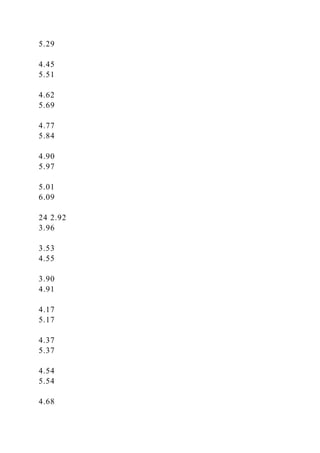

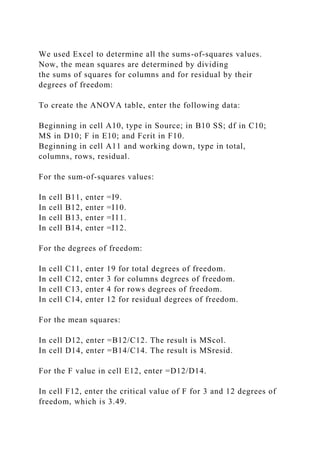

![conocidas. Las

variables manipuladas han sido: igualdad o desigualdad del

tamaño de los

grupos, tamaño muestral total y de los grupos; coefi ciente de

variación

del tamaño muestral; forma de la distribución e igualdad o

desigualdad de

la forma en los grupos; y emparejamiento entre el tamaño

muestral con

el grado de contaminación en la distribución. Resultados: los

resultados

muestran que el estadístico F es robusto en términos de error de

Tipo I en

el 100% de los casos estudiados, independientemente de las

condiciones

manipuladas.

Palabras clave: estadístico F, ANOVA, robustez, asimetría,

curtosis.

Psicothema 2017, Vol. 29, No. 4, 552-557

doi: 10.7334/psicothema2016.383

Received: December 14, 2016 • Accepted: June 20, 2017

Corresponding author: María J. Blanca

Facultad de Psicología

Universidad de Málaga

29071 Málaga (Spain)

e-mail: [email protected]

Non-normal data: Is ANOVA still a valid option?

553](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/anovainterpretationset1studythisscenarioandanova-221014163318-bc8c28fa/85/ANOVA-Interpretation-Set-1-Study-this-scenario-and-ANOVA-docx-179-320.jpg)