An introdution to reliability and maintainability engineering 2nd ed Edition Ebeling

An introdution to reliability and maintainability engineering 2nd ed Edition Ebeling

An introdution to reliability and maintainability engineering 2nd ed Edition Ebeling

![2 An Introduction to Reliability and Maintainability Engineering

coming apart from the main body of the tire. Because of the excessive number of

failures, Firestone was forced to recall 7.5 million tires. On November 8, 1940, the

Tacoma Narrows Bridge, five months old, collapsed into Puget Sound from vibra-

tions caused by high winds. Metal fatigue induced by several months of oscillations

led to the failure. The Manus River bridge (Greenwich, Connecticut) collapsed in

1983, killing three people and injuring three. While there is disagreement on the

cause of the disaster, blame has been placed on the original design, on corrosion that

had caused undetected displacement of the pin-and-hanger suspension assembly, on

poor maintenance, and on inadequate inspections. The Hartford (Connecticut) Civic

Center Coliseum roof collapsed in 1978 from structural failure due to the weight of

the snow and ice accumulated on the roof. A major shortcoming in the roof frame

system was the lack of redundancy of members to carry loads when other individual

members failed. An inadequate safety margin may also have contributed. The Three

Mile Island disaster in 1979, which resulted in a partial meltdown of a nuclear reac-

tor, was a result ofboth mechanical and human error. When a backup cooling system

was down for routine maintenance, air cut off the flow ofcooling water to the reactor.

Warning lights were hidden by maintenance tags. An emergency relief valve failed

to close, causing additional water to be lost from the cooling system. Operators were

either reading gauges that were not working properly or taking the wrong actions

on the basis of those that were operating. The 1986 explosion of the space shuttle

Challenger was a result of the failure of the rubber O-rings that were used to seal

the four sections of the booster rockets. The below-freezing temperatures before the

launch contributed to the failure by making the rubber brittle.!

From the above examples one can conclude that the impact of product and sys-

tem failures varies from minor inconvenience and costs to personal injury, signif-

icant economic loss, and death. Causes of these failures include bad engineering

design, faulty construction or manufacturing processes, human error, poor mainte-

nance, inadequate testing and inspection, improper use, and lack ofprotection against

excessive environmental stress. Under current laws and recent court decisions, the

manufacturer can be held liable for failing to account properly for product safety

and reliability. Engineers responsible for product design must therefore include both

reliability and maintainability as design criteria. The objective of this text is to intro-

duce the technical manager and the engineer to the concepts, models, and analysis

techniques that form the basis of reliability and maintainability engineering.

This, then, is a book on the failure and repair characteristics ofsystems, products,

and their component parts. Reliability and maintainability engineering attempts to

study, characterize, measure, and analyze the failure and repair ofsystems in order to

improve their operational use by increasing their design life, eliminating or reducing

the likelihood of failures and safety risks, and reducing downtime, thereby increas-

ing available operating time. Closely associated with reliability and maintainability

for systems or components that can be repaired or restored to an operating state once

they have failed is the concept of availability. Availability measures the combined

I Details ofthese and other disasters may be found in the highly interesting book When Technology Fails

[Schlager, 1994].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/60222-250303060215-7ac13b08/75/An-introdution-to-reliability-and-maintainability-engineering-2nd-ed-Edition-Ebeling-23-2048.jpg)

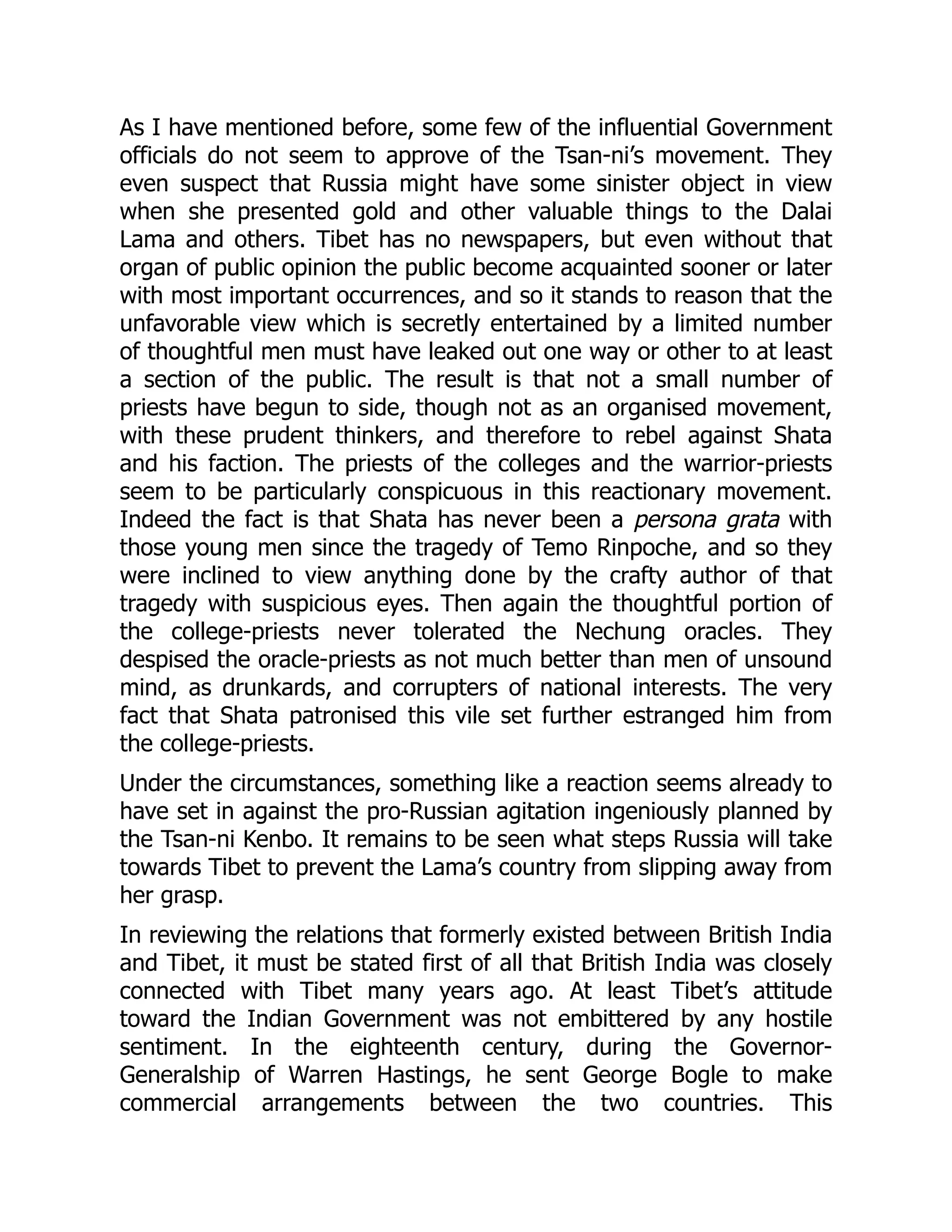

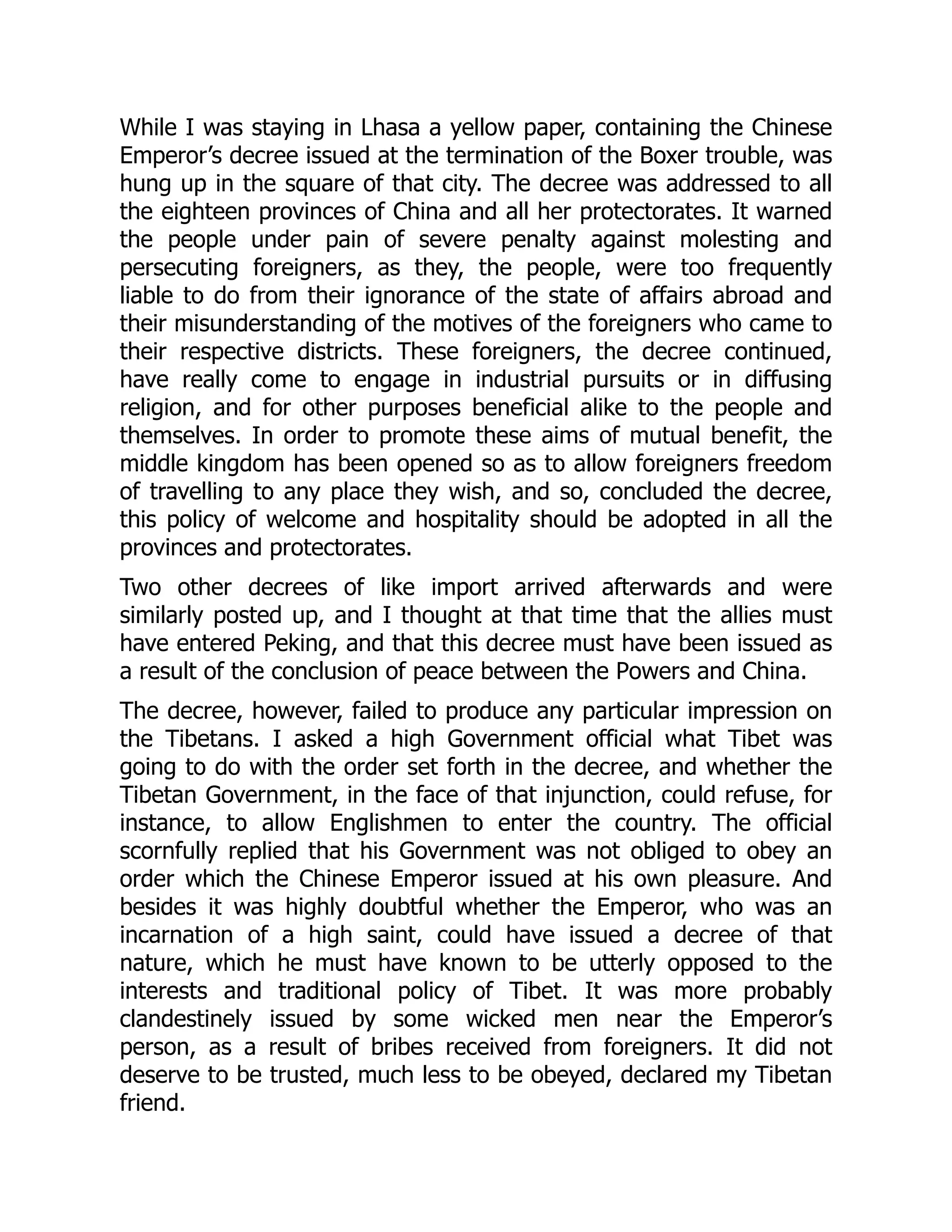

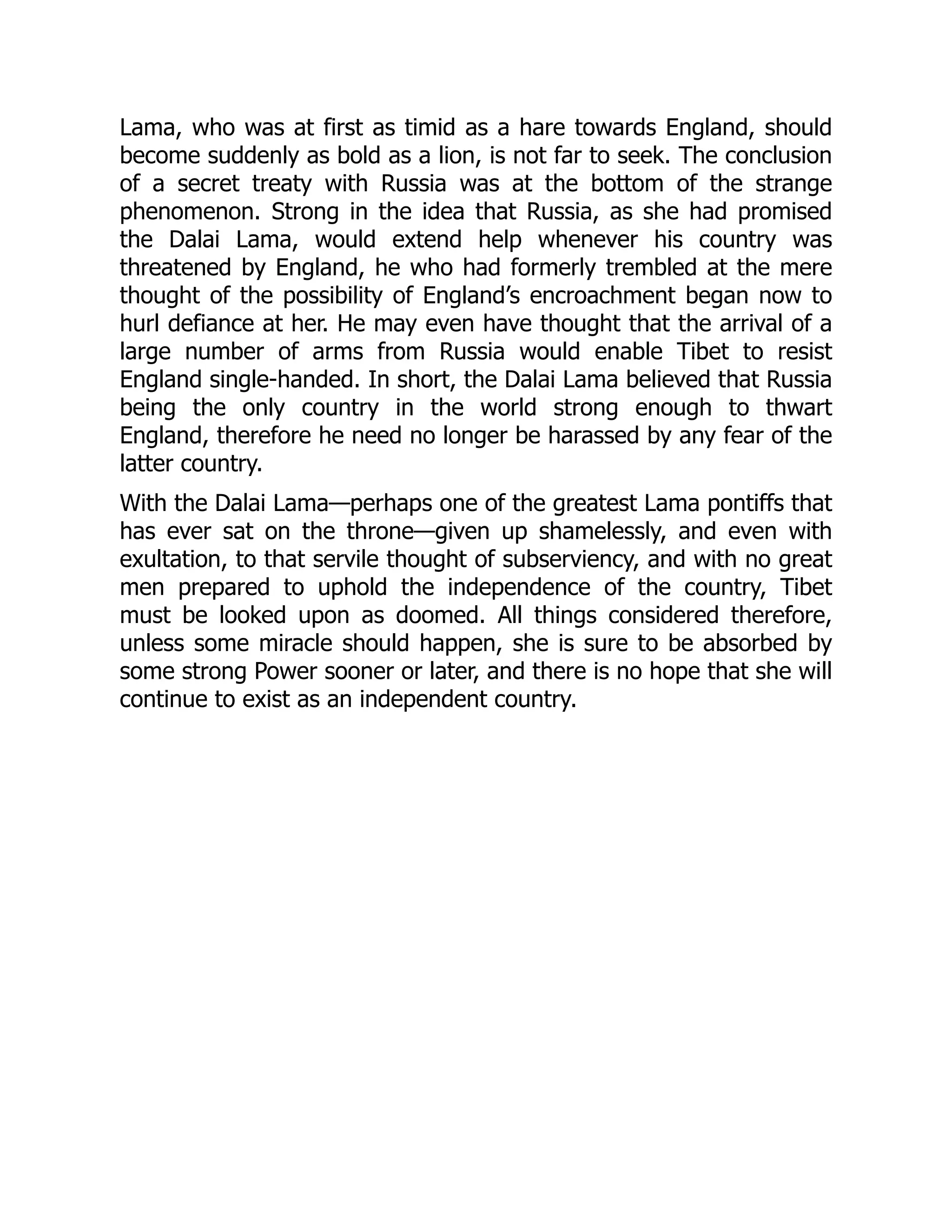

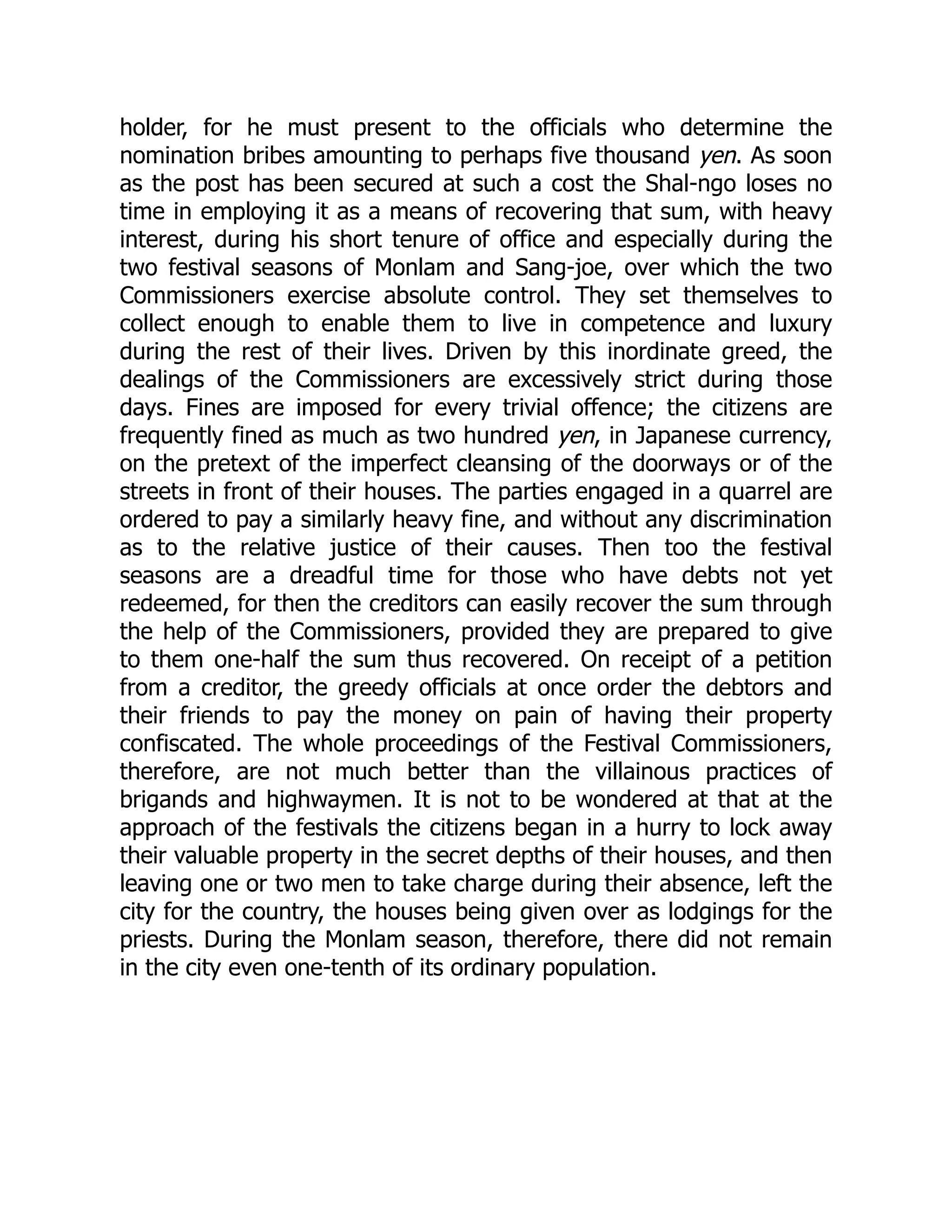

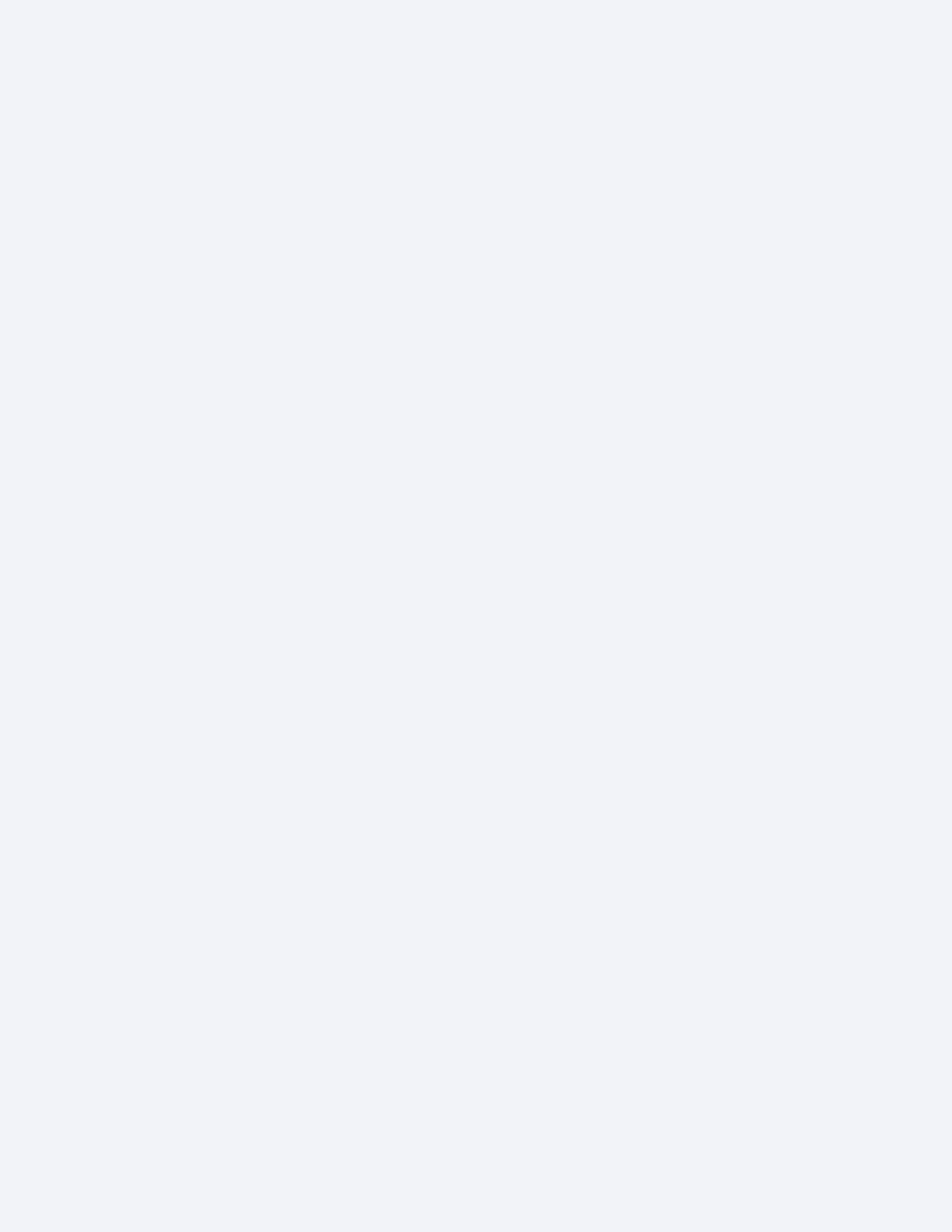

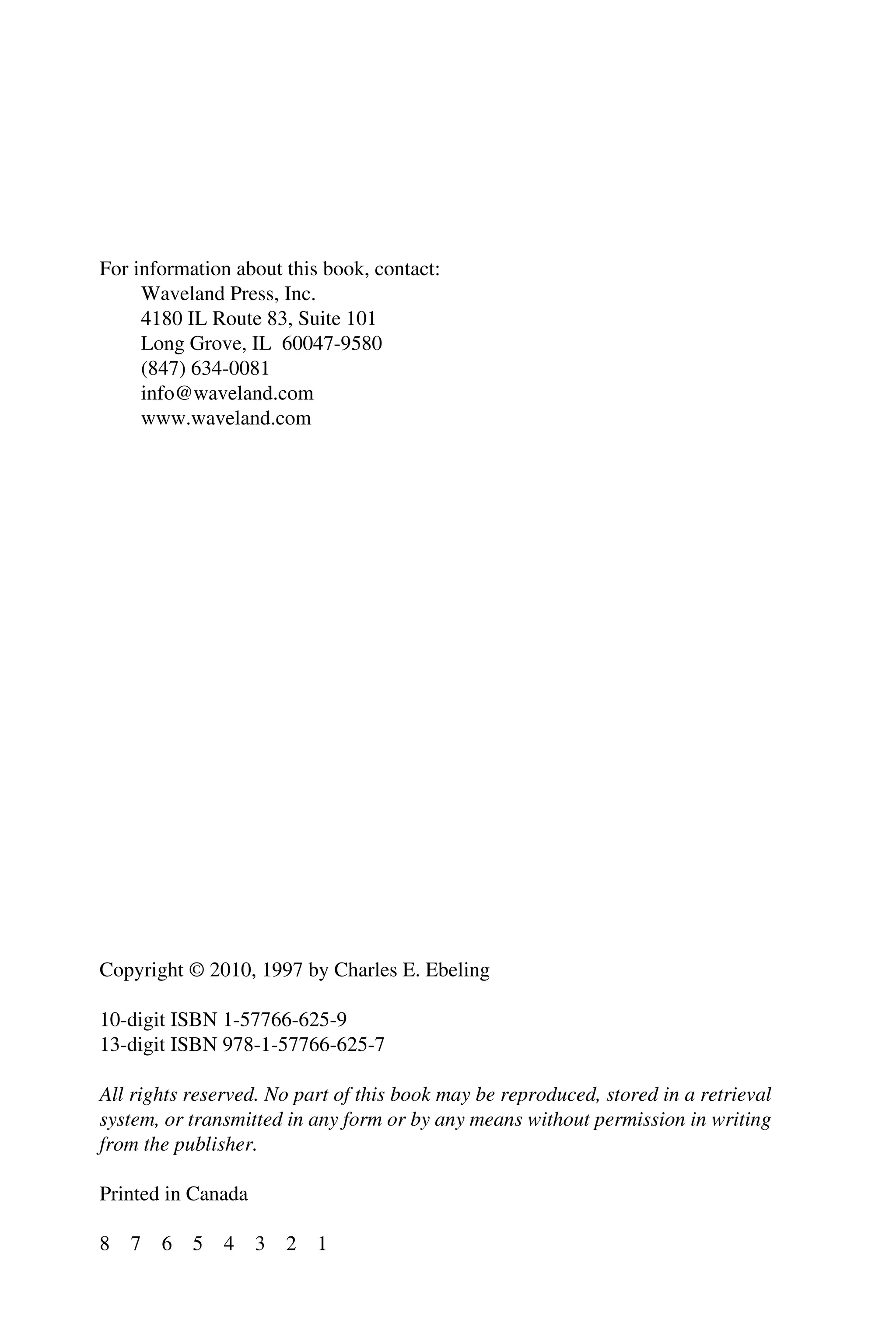

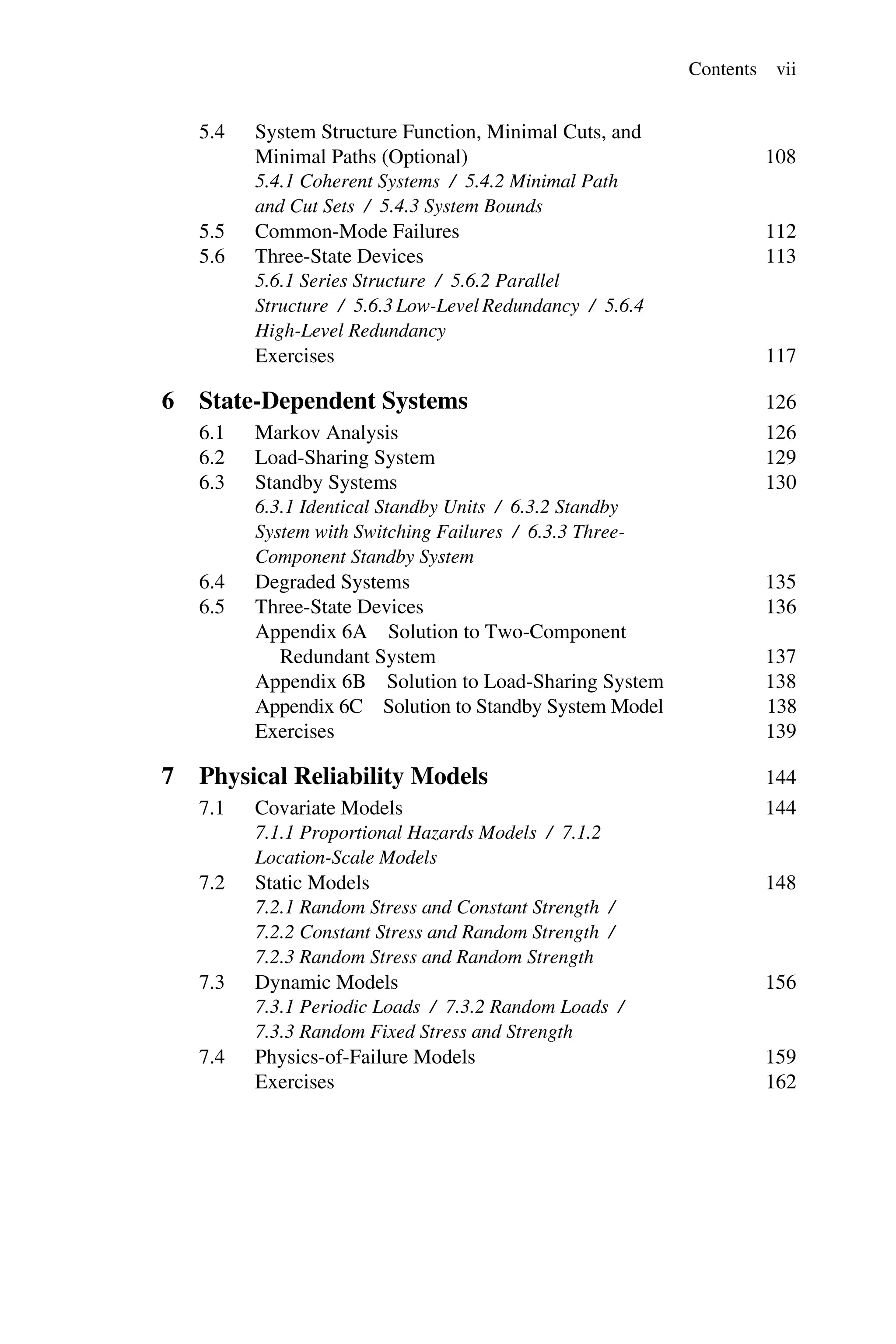

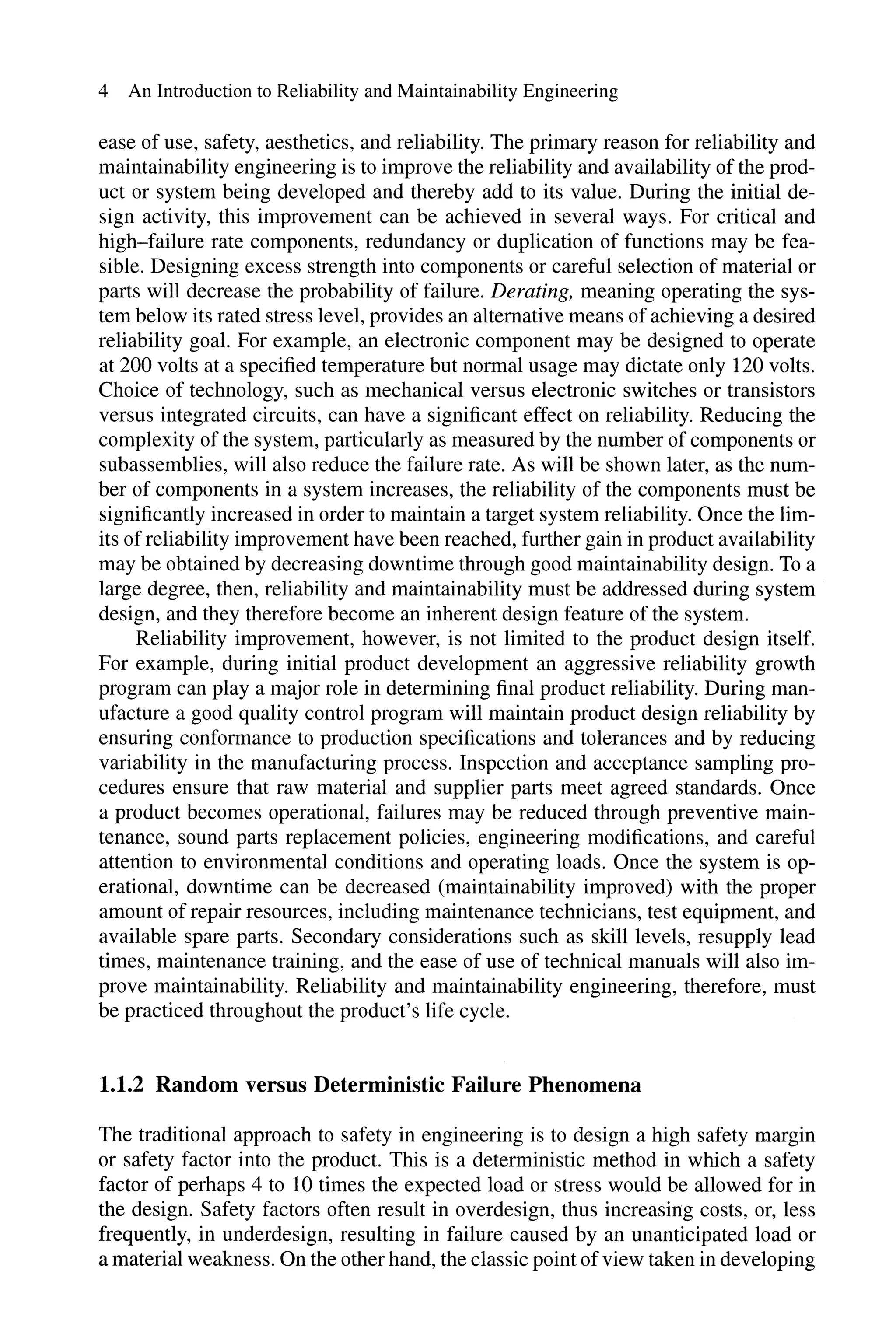

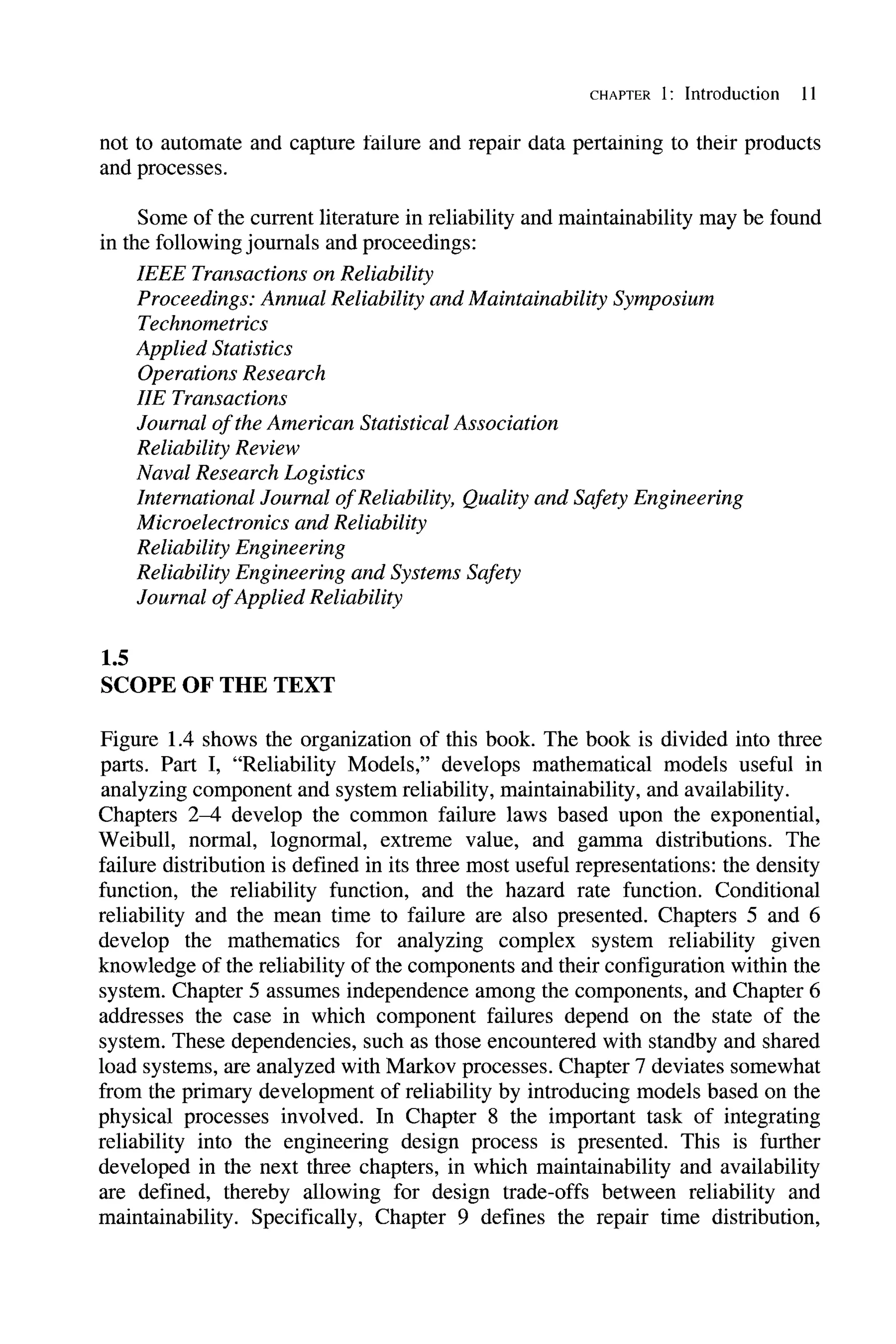

![CHAFfER 1: Introduction 7

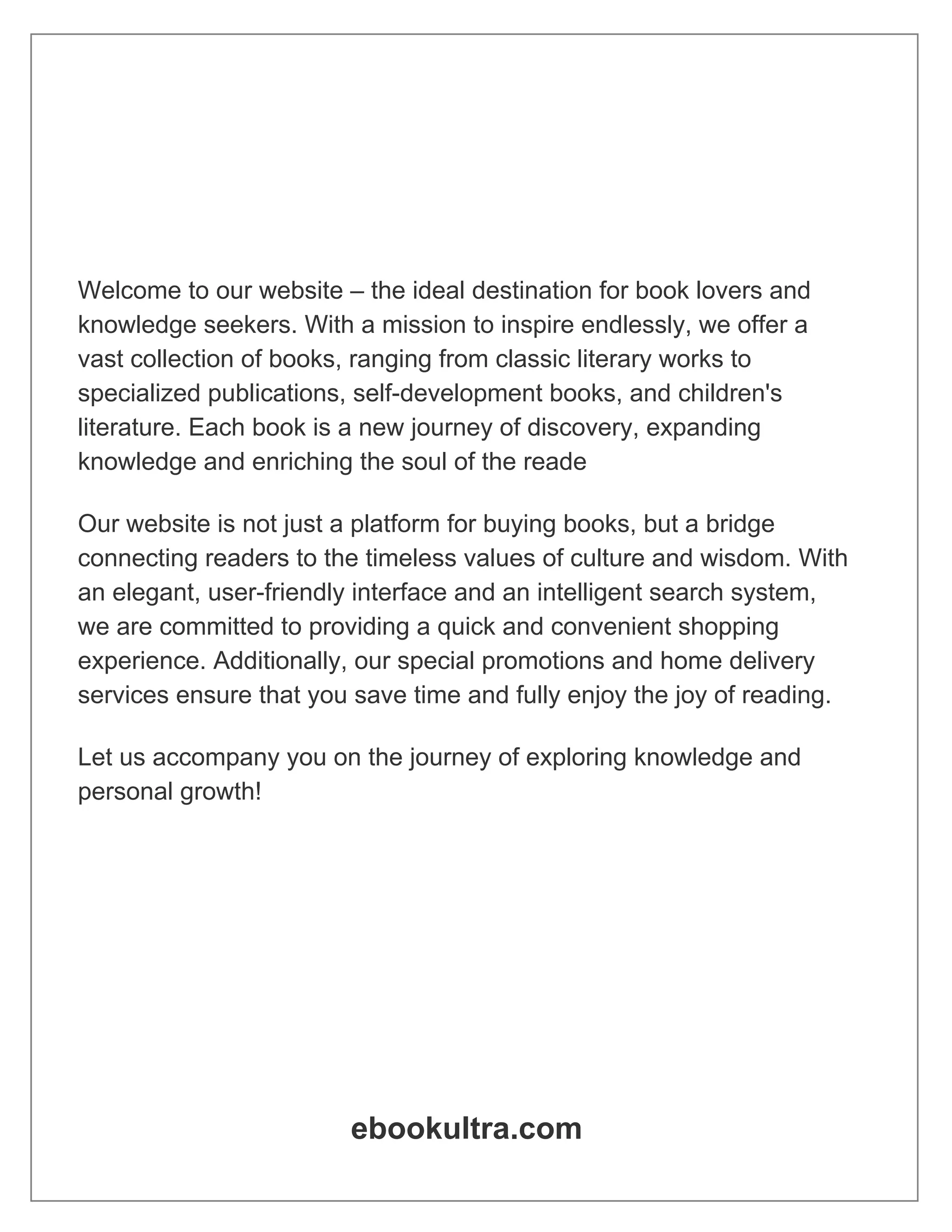

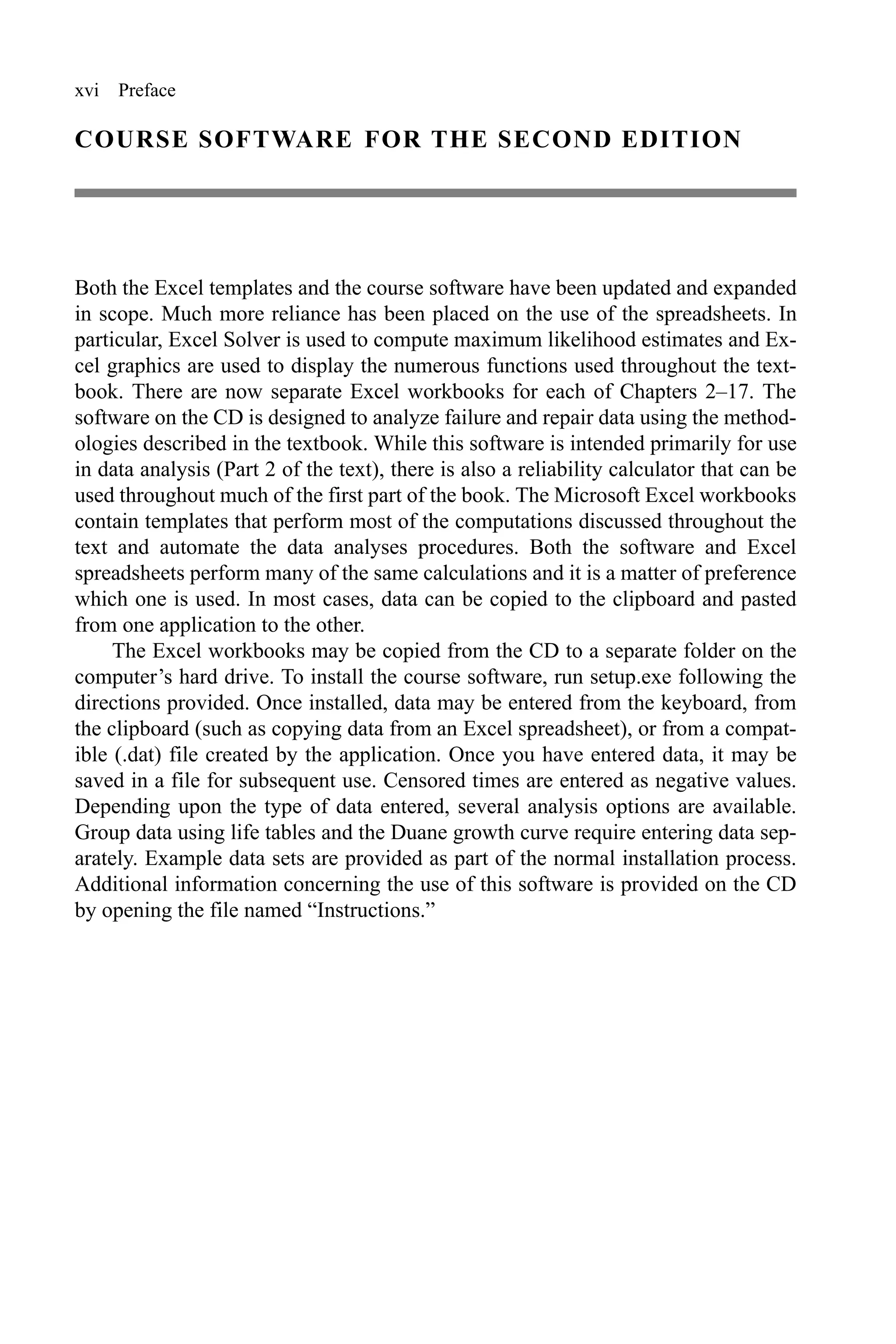

TABLE 1.2

Reliability test data results

Motor

1-100 101-200 201-300 301-400 401-500 Total

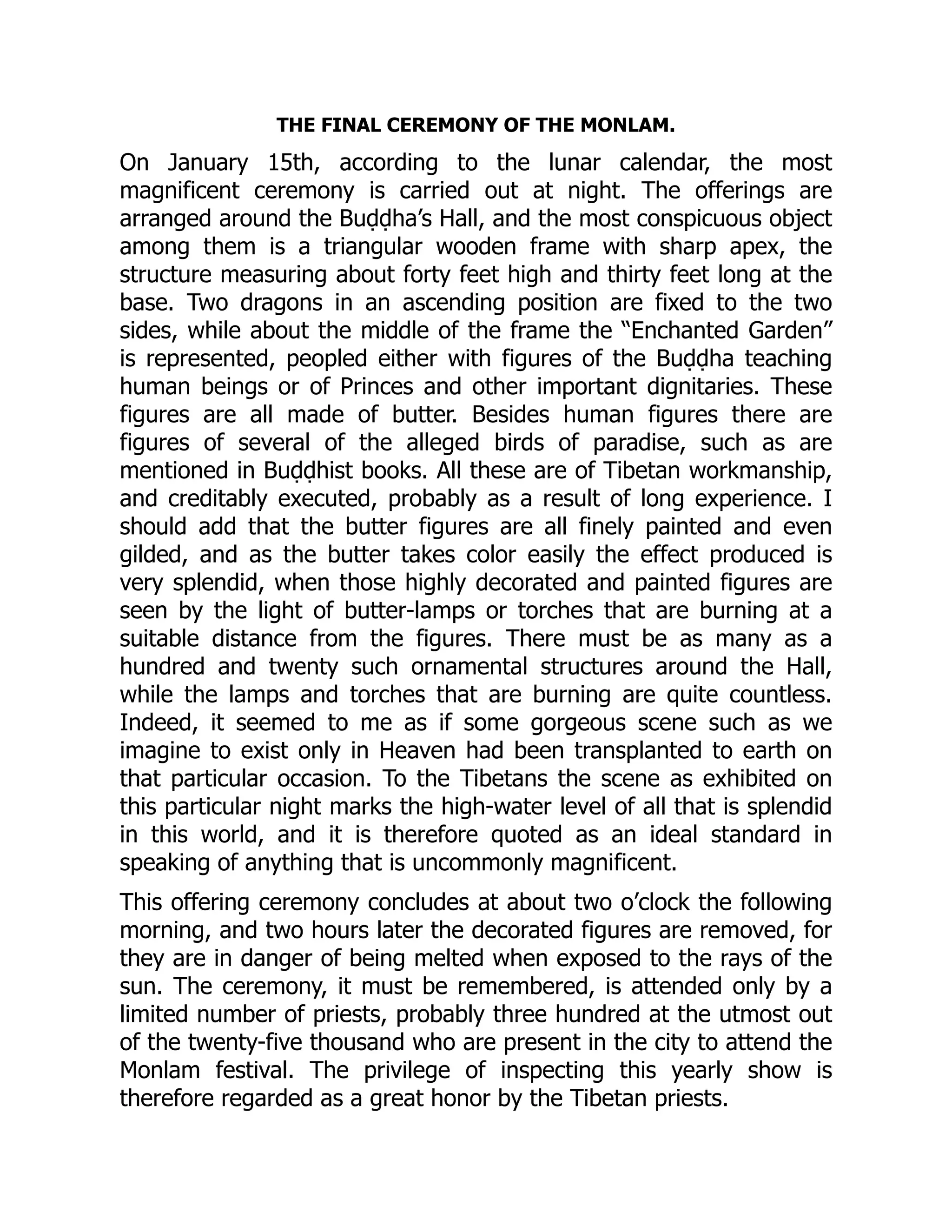

Number tested 12

Hours on test 2540

Number failed 1

Failure rate 0.000394

1.3

APPLICATIONS

11 12

2714 2291

0 1

0 0.000436

12 15 62

1890 2438 11873

5 7 14

0.002646 0.002871 0.001179

The types of problems solved through the use of reliability and maintainability con-

cepts are illustrated by the following examples.

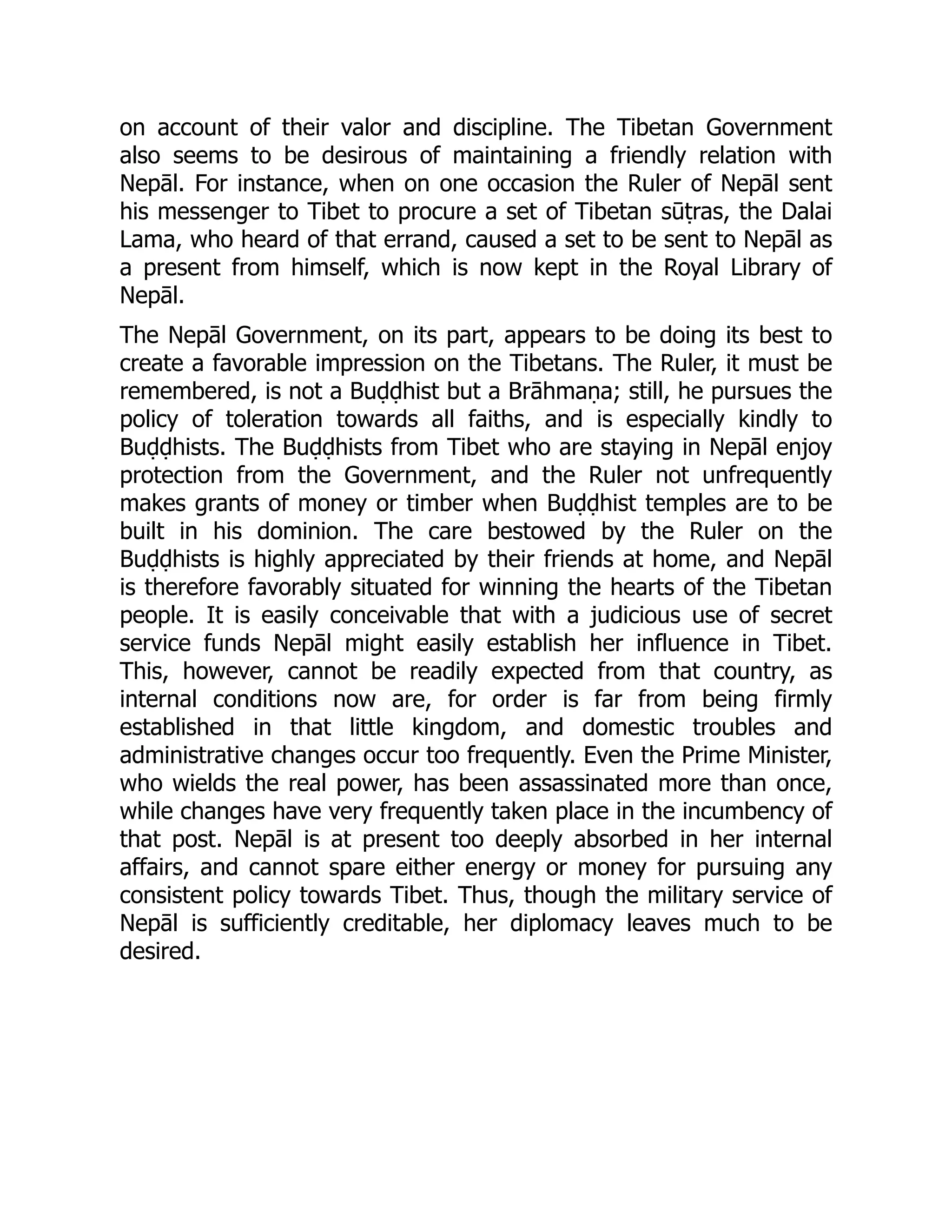

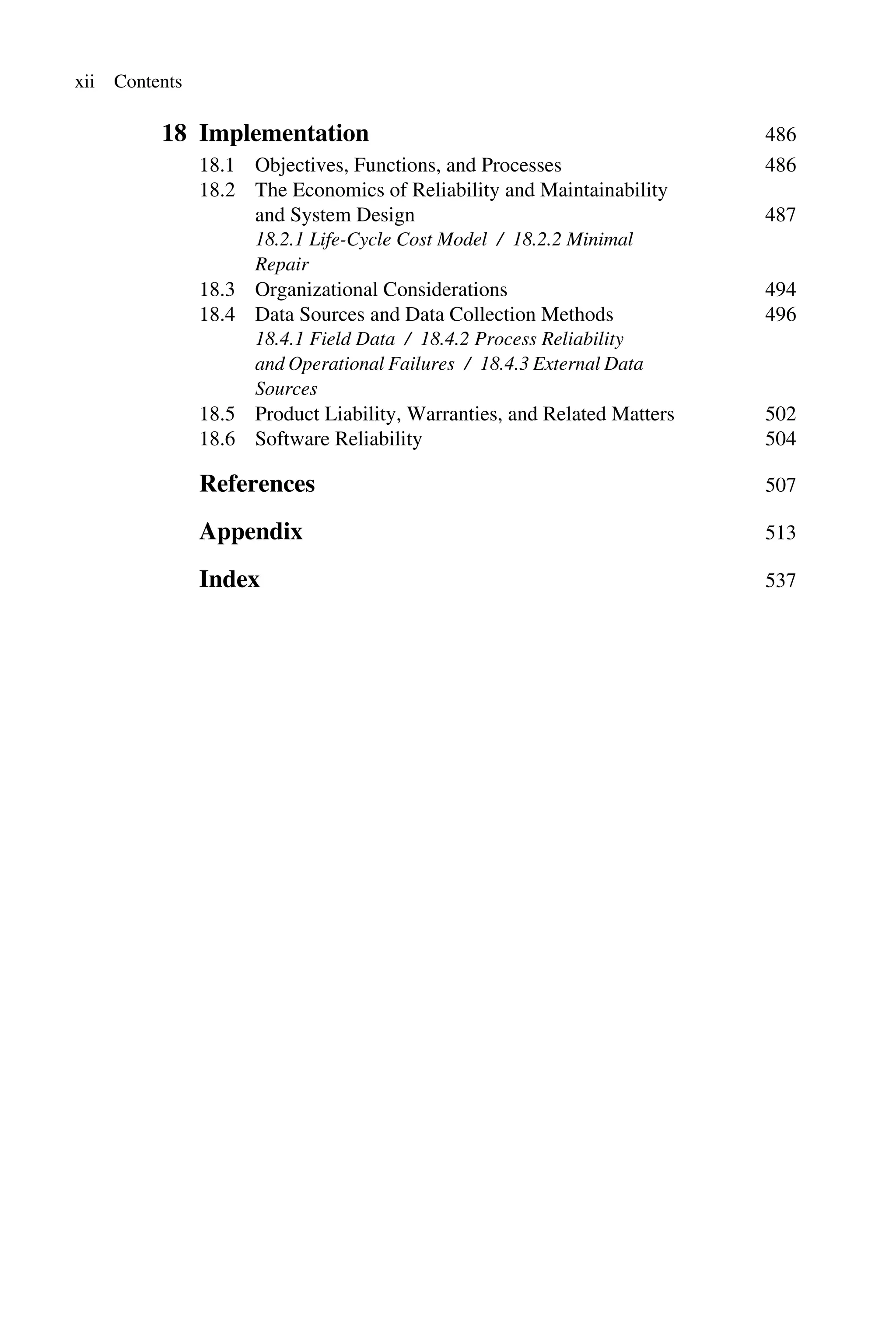

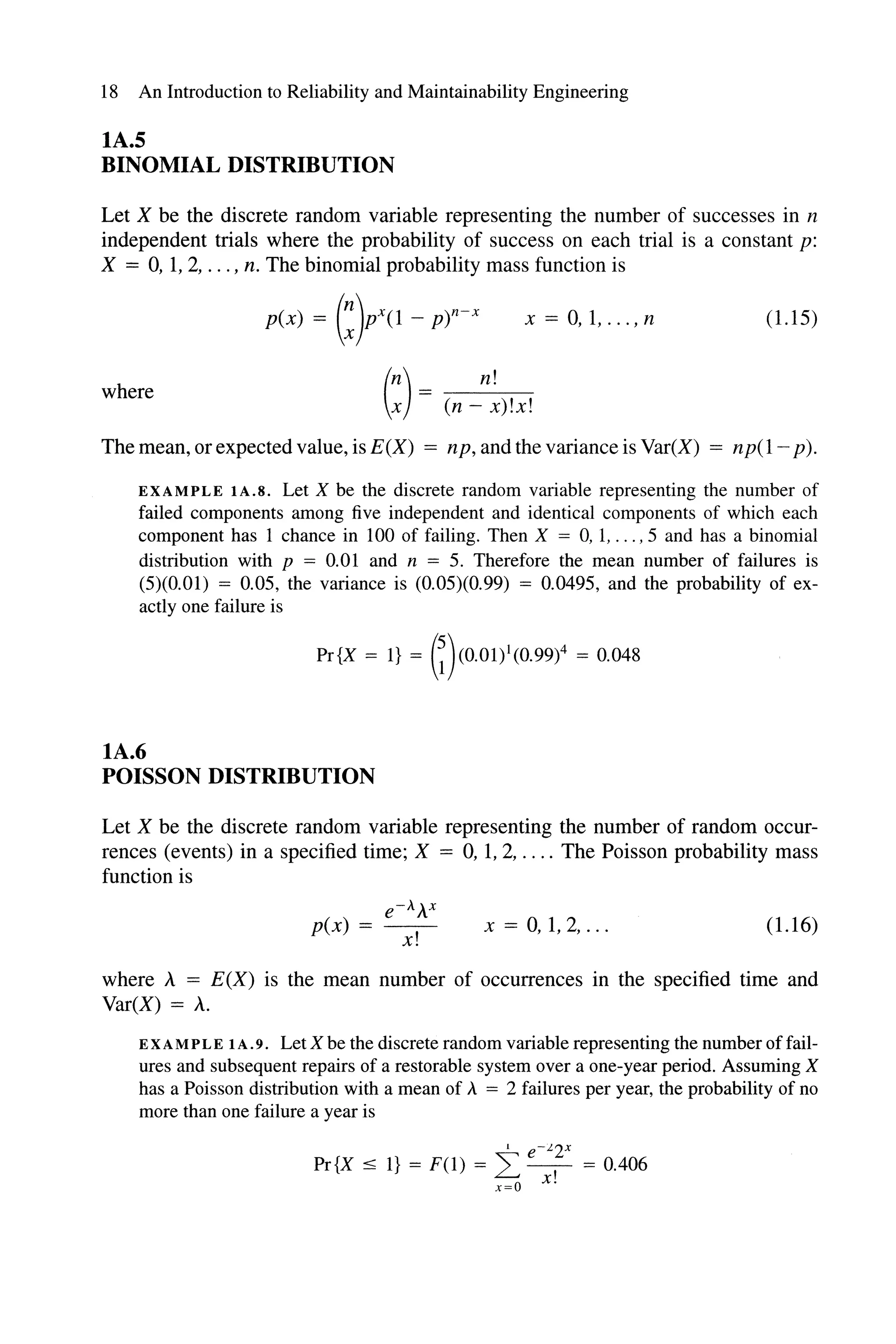

EXAMPLE 1.1. The B. A. Miller Company manufactures small motors for use in house-

hold appliances such as washing machines, dryers, refrigerators, and vacuum cleaners.

It has recently designed a new motor that has experienced the abnormally high failure

rate of 43 failures among the first 1000 motors produced. Several of these failures were

observed during final product testing by the appliance manufacturer. These motors were

inspected, and it appeared that the bearing case was turning in its seat. The sealed ball

bearings, however, appeared to be okay. Possible causes of these failures included faulty

design, defective material, and a manufacturing (tolerance) problem. The company initi-

ated an aggressive program of accelerated life testing of motors randomly selected from

the production line. As a result of the testing program, it observed that those motors pro-

duced near the end of a production run were failing at a higher rate than those at the start

of the run. Table 1.2 summarizes the results of the testing program, which are displayed

graphically in Fig. 1.1.

The failure rate is computed by dividing the number of failures by the total num-

ber of hours on test. Dividing total hours on test by the number of failures provides an

0.0030

.... 0.0025

] 0.0020

....

<I)

c.. 0.0015

'"

!:l

.a

'<a

0.0010

~

0.0005

0

1-100

FIGURE 1.1

Failure rates of motors.

101-200 201-300 301-400 401-500 Touu

Production number](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/60222-250303060215-7ac13b08/75/An-introdution-to-reliability-and-maintainability-engineering-2nd-ed-Edition-Ebeling-28-2048.jpg)

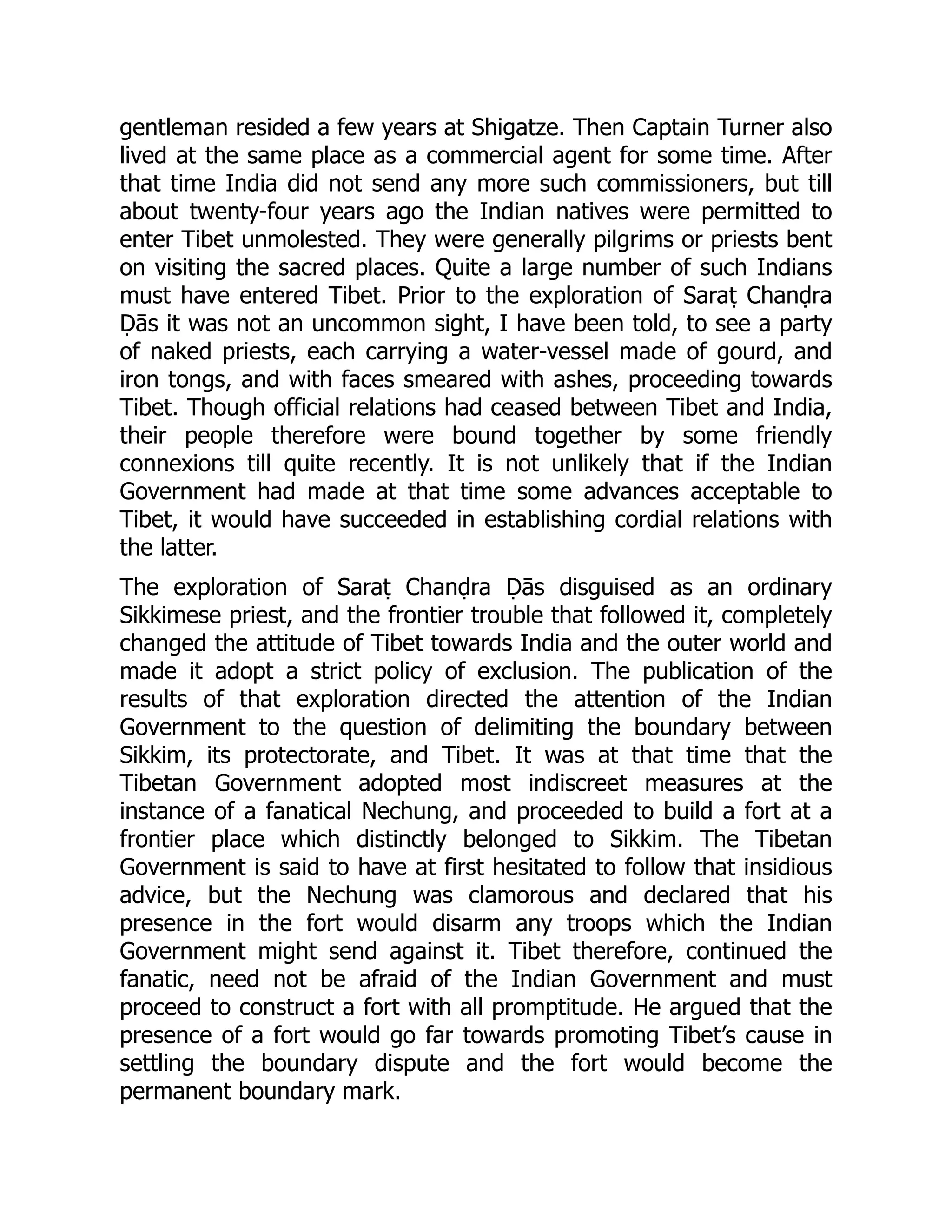

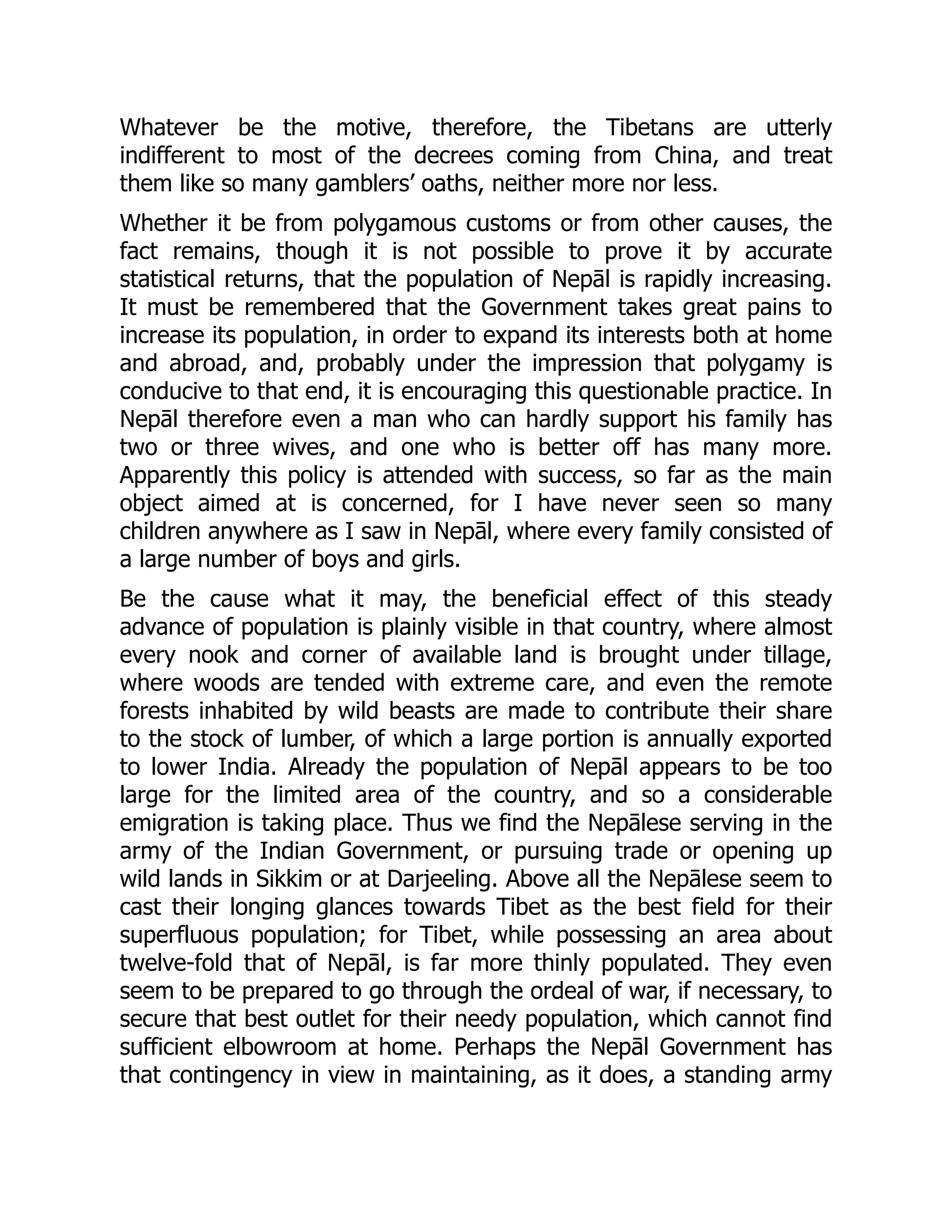

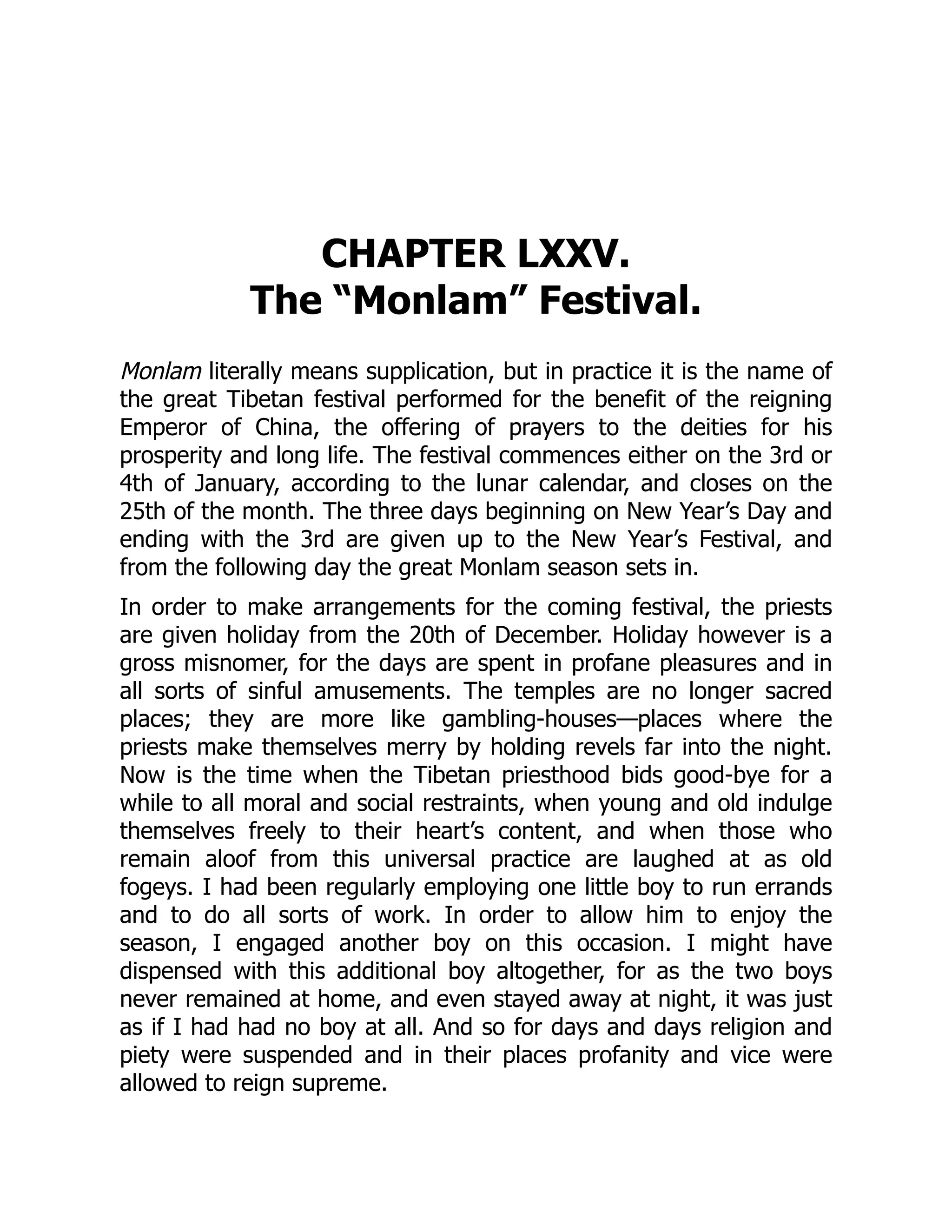

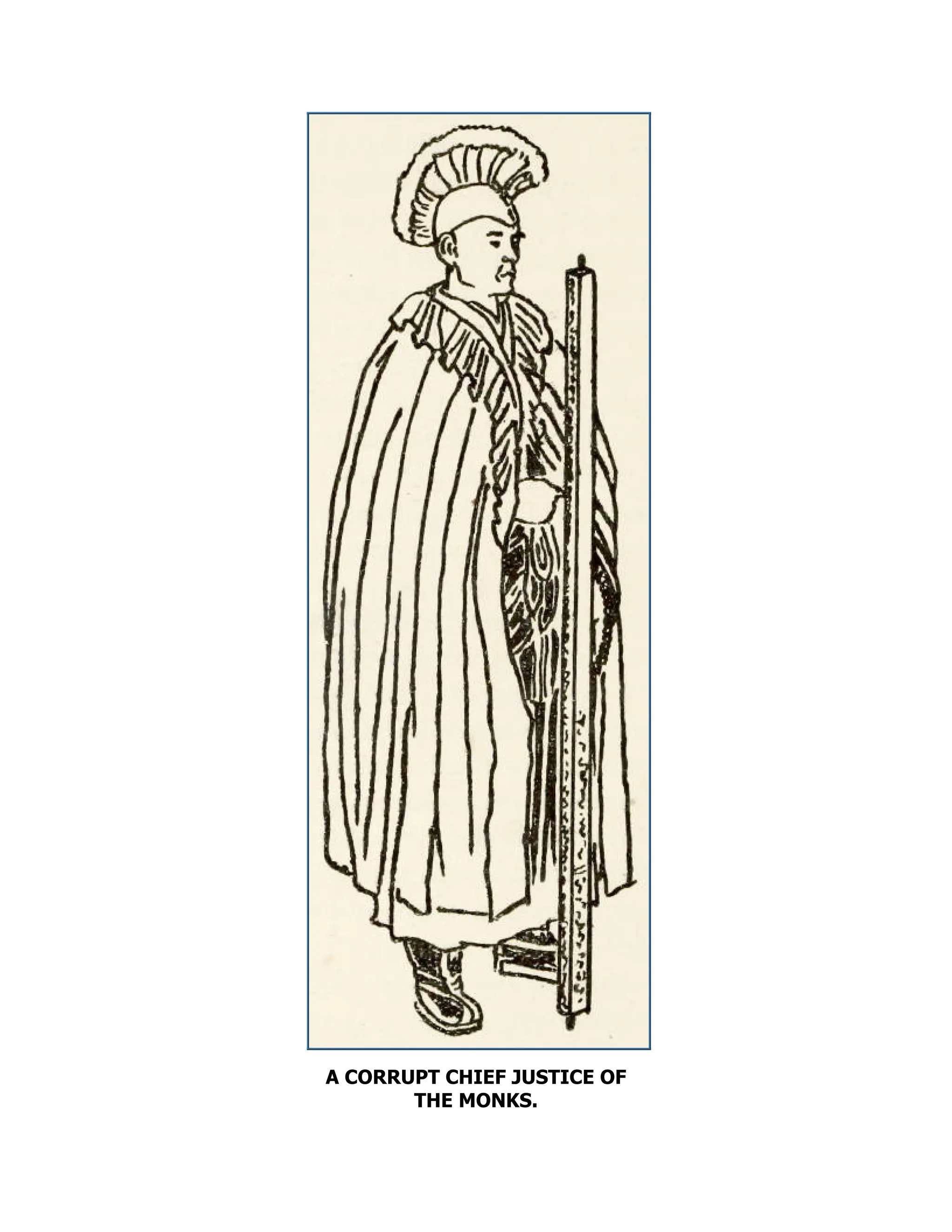

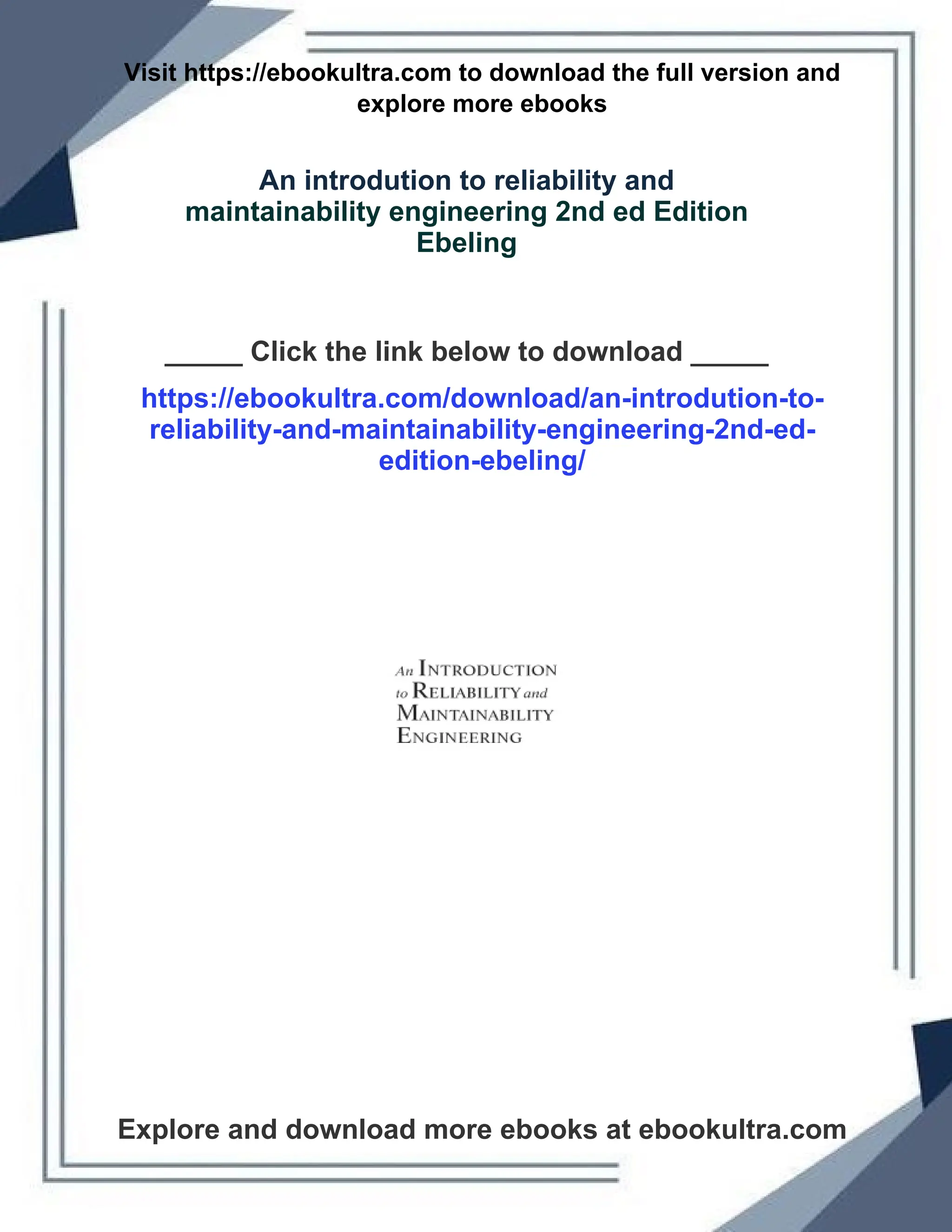

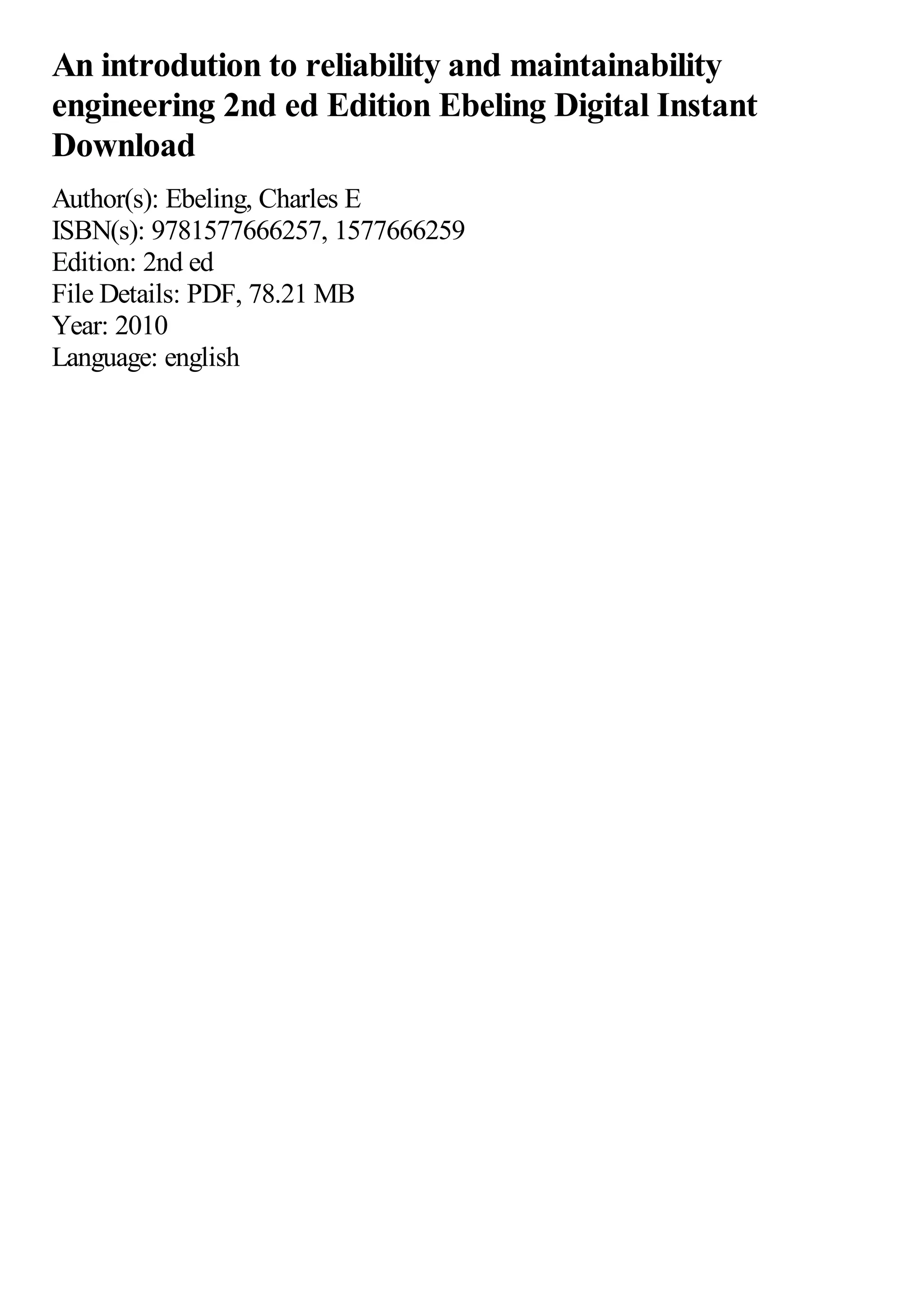

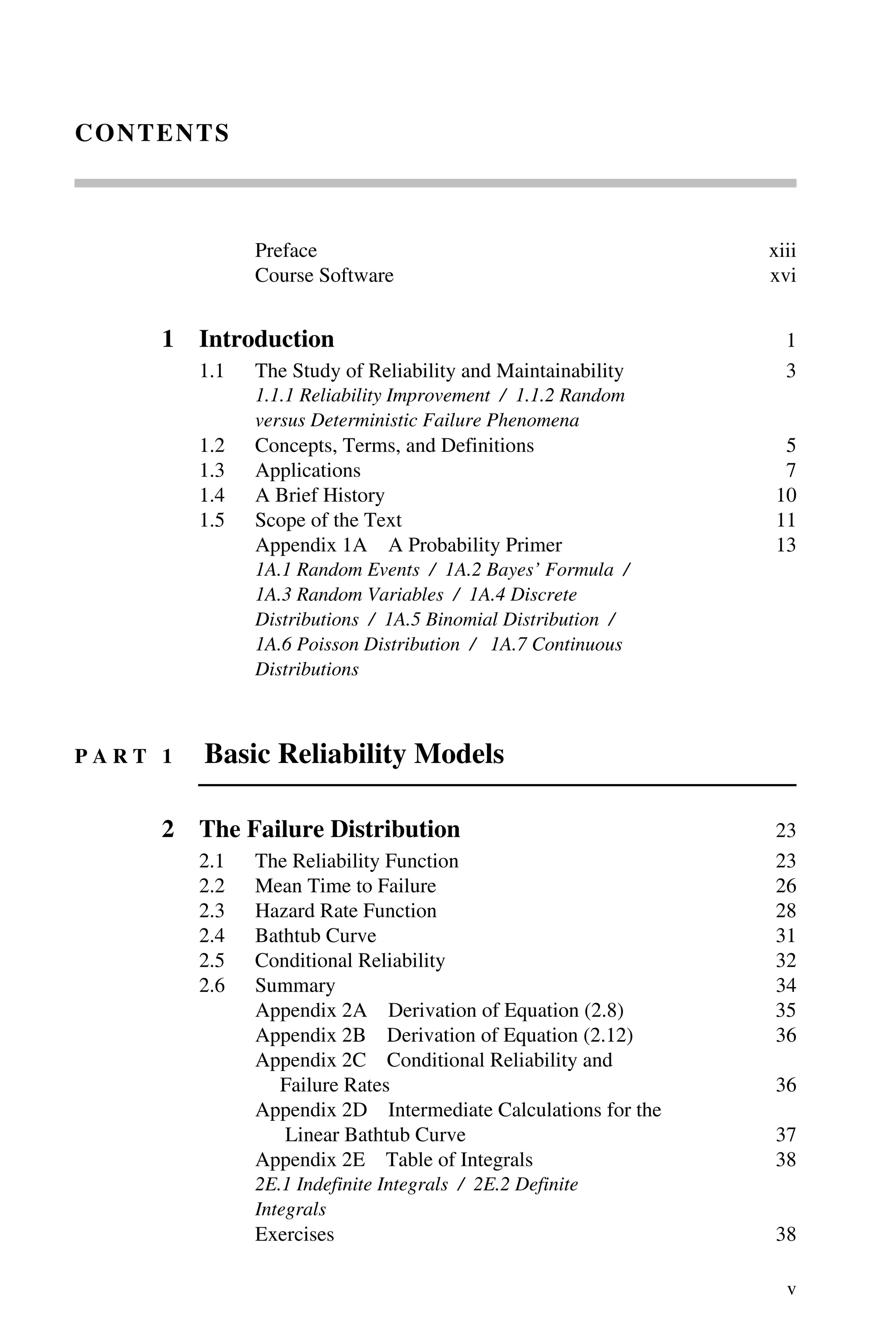

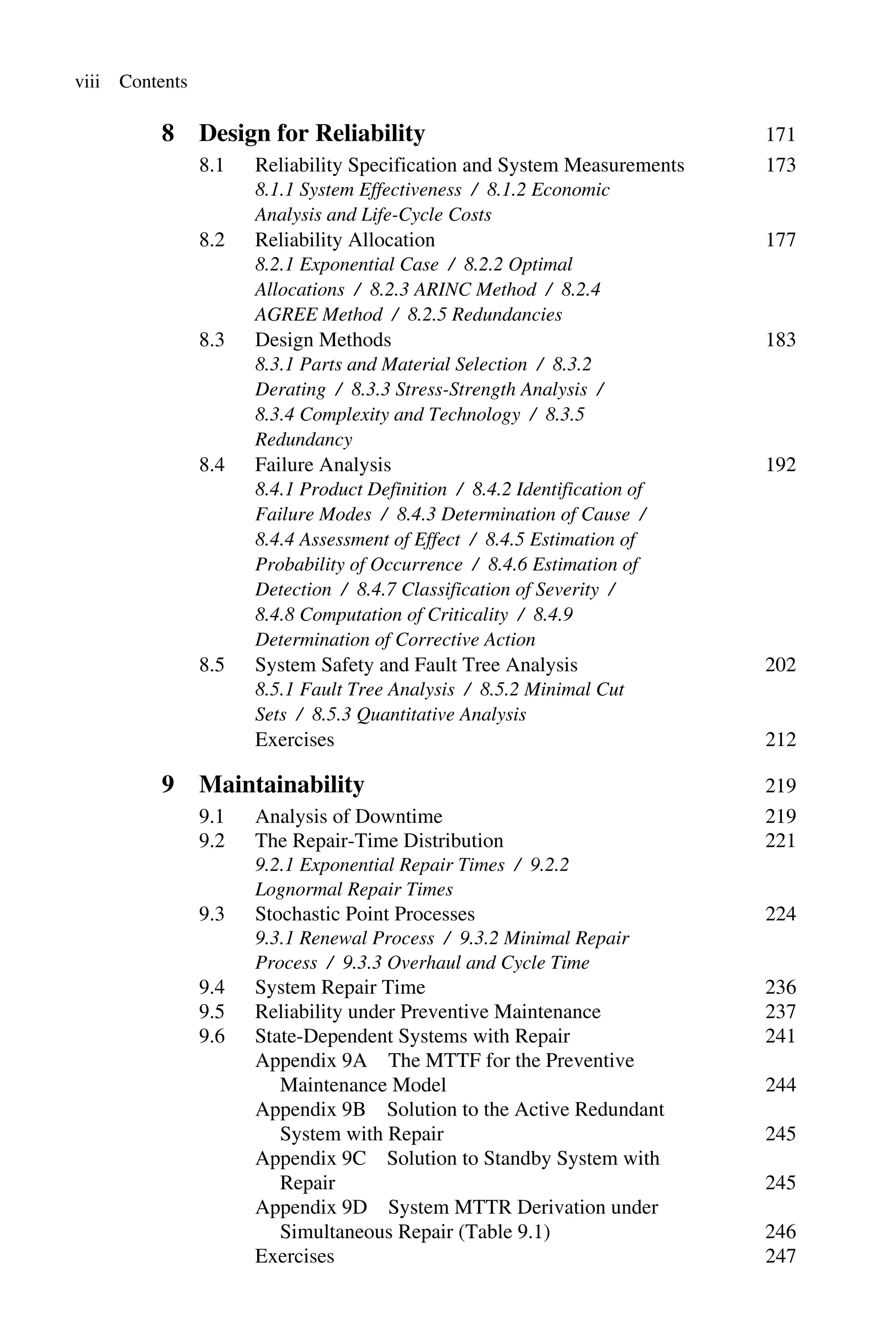

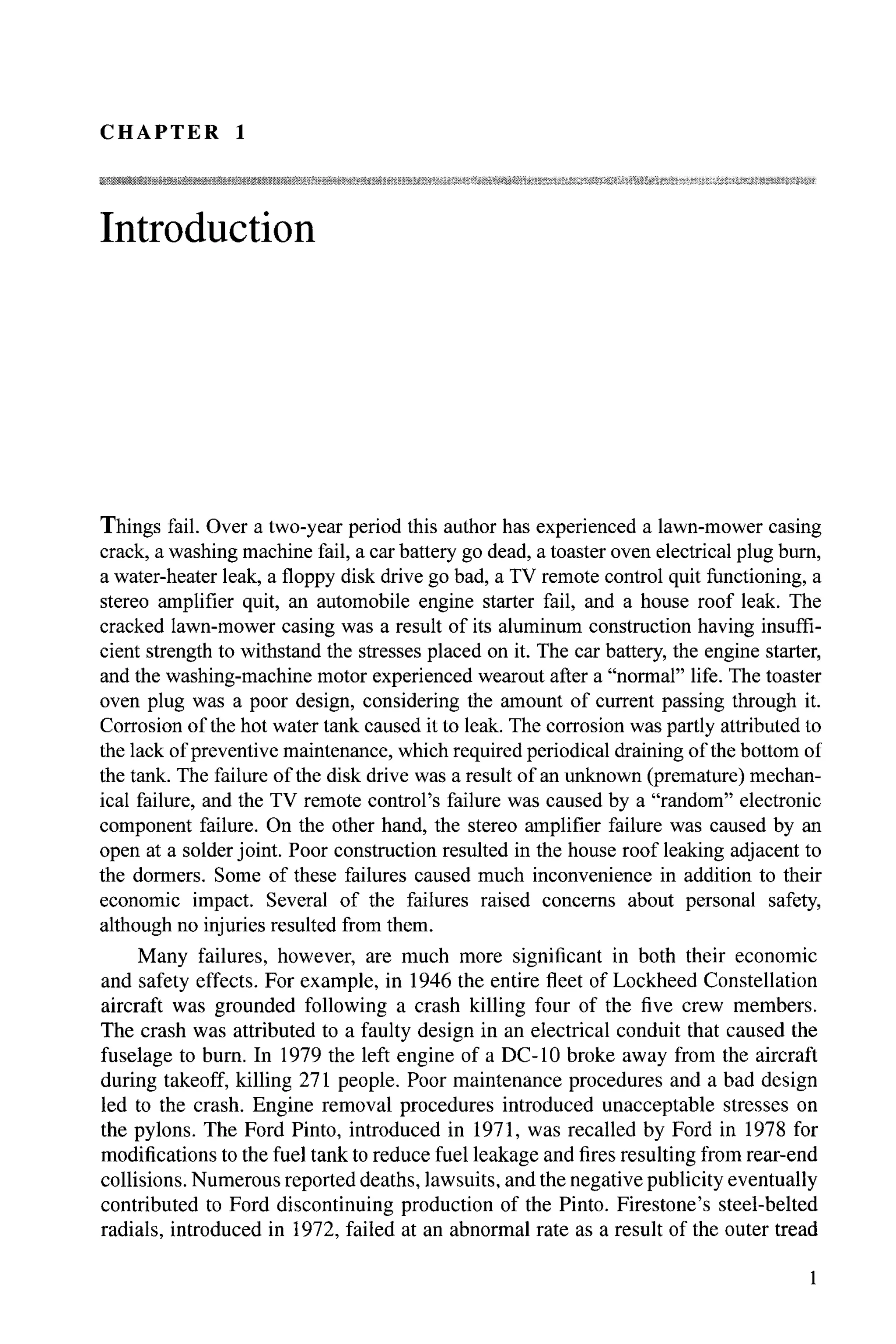

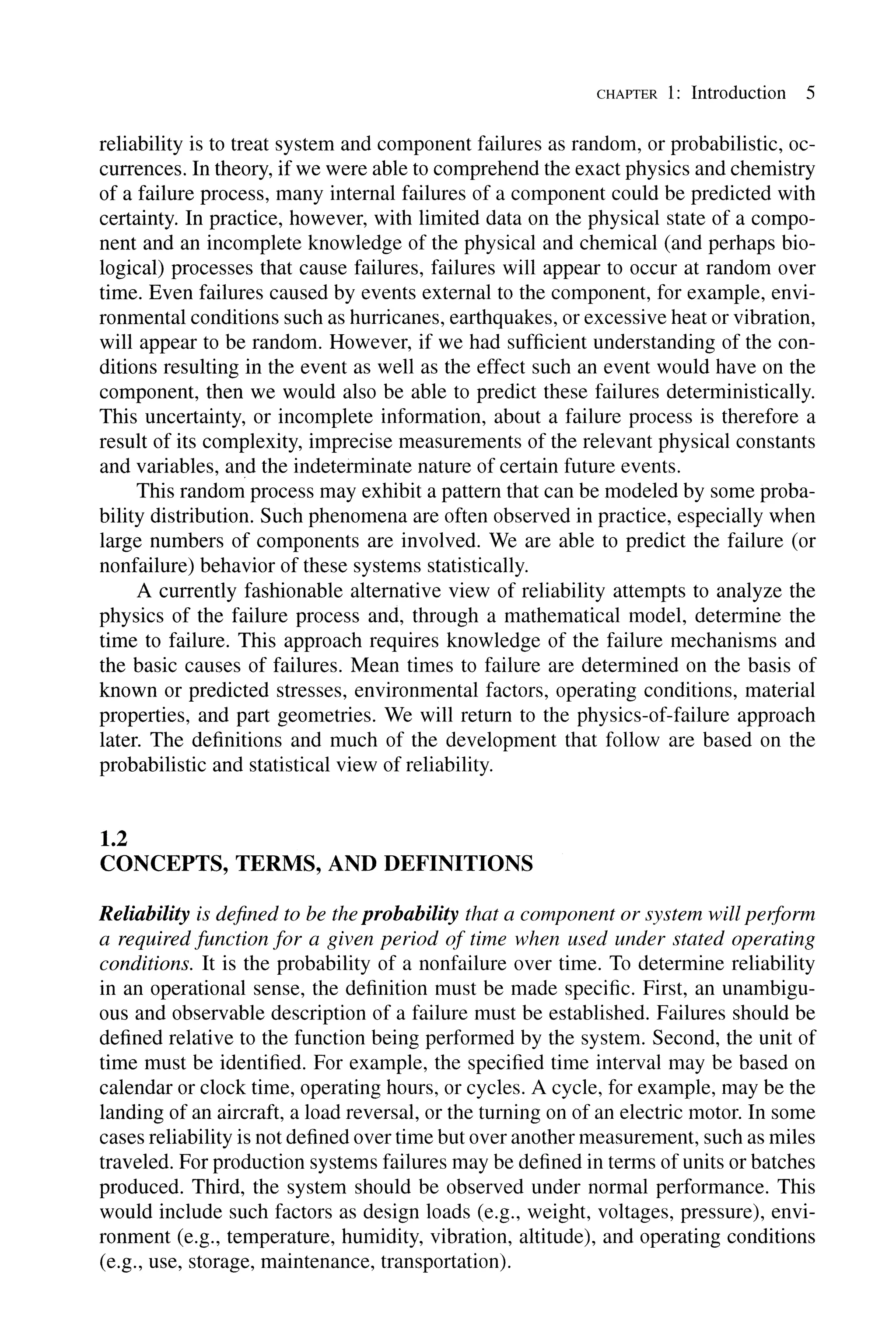

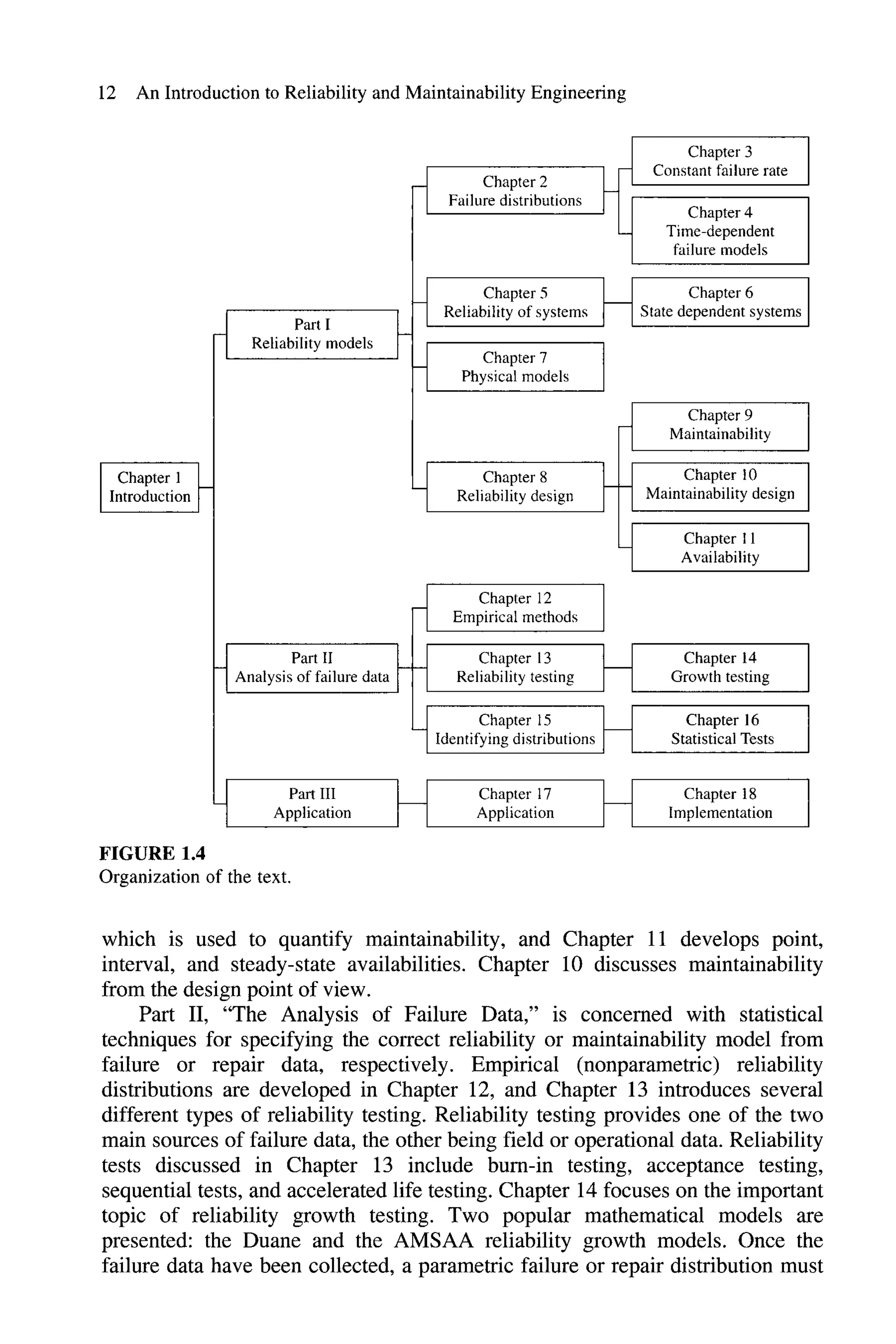

![CHAPTER 1: Introduction 9

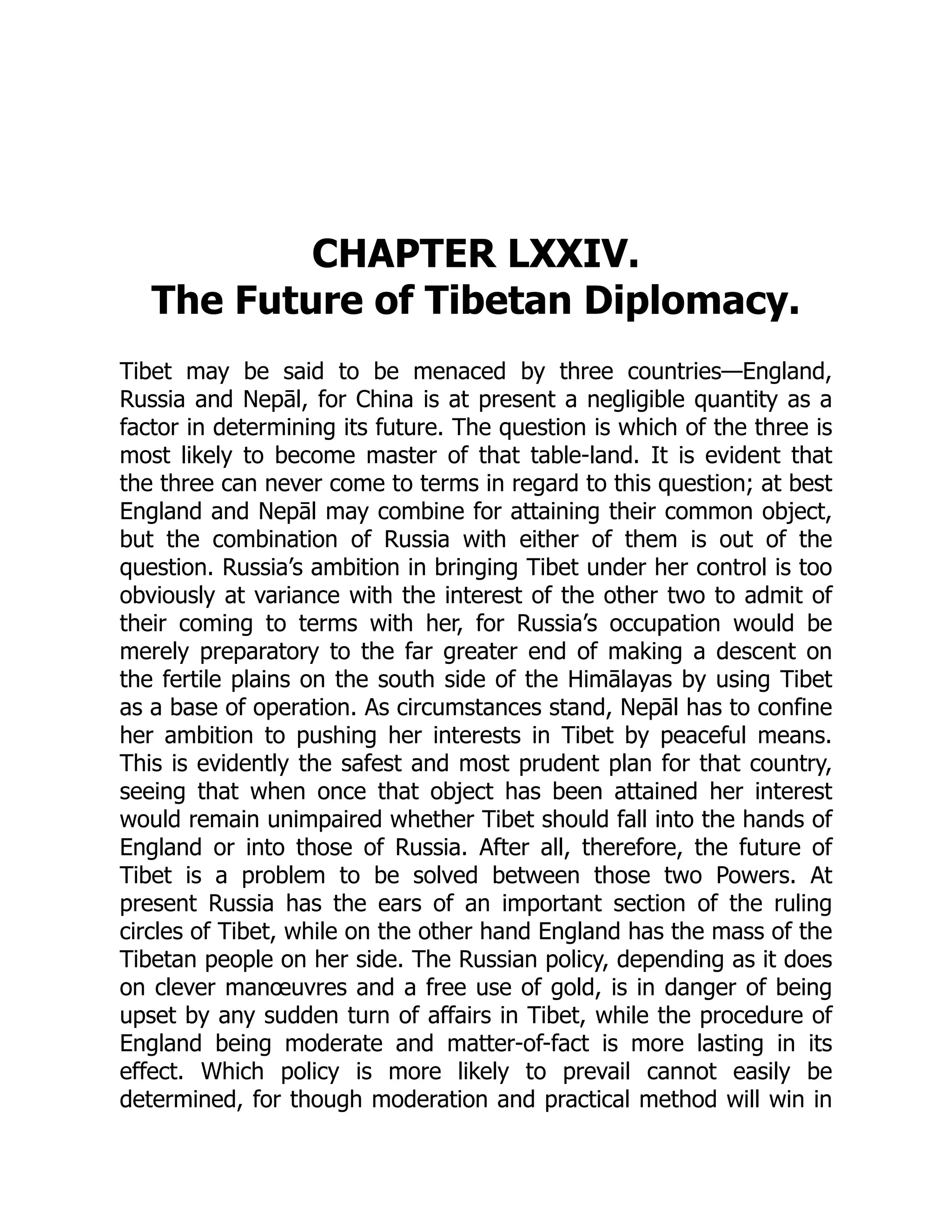

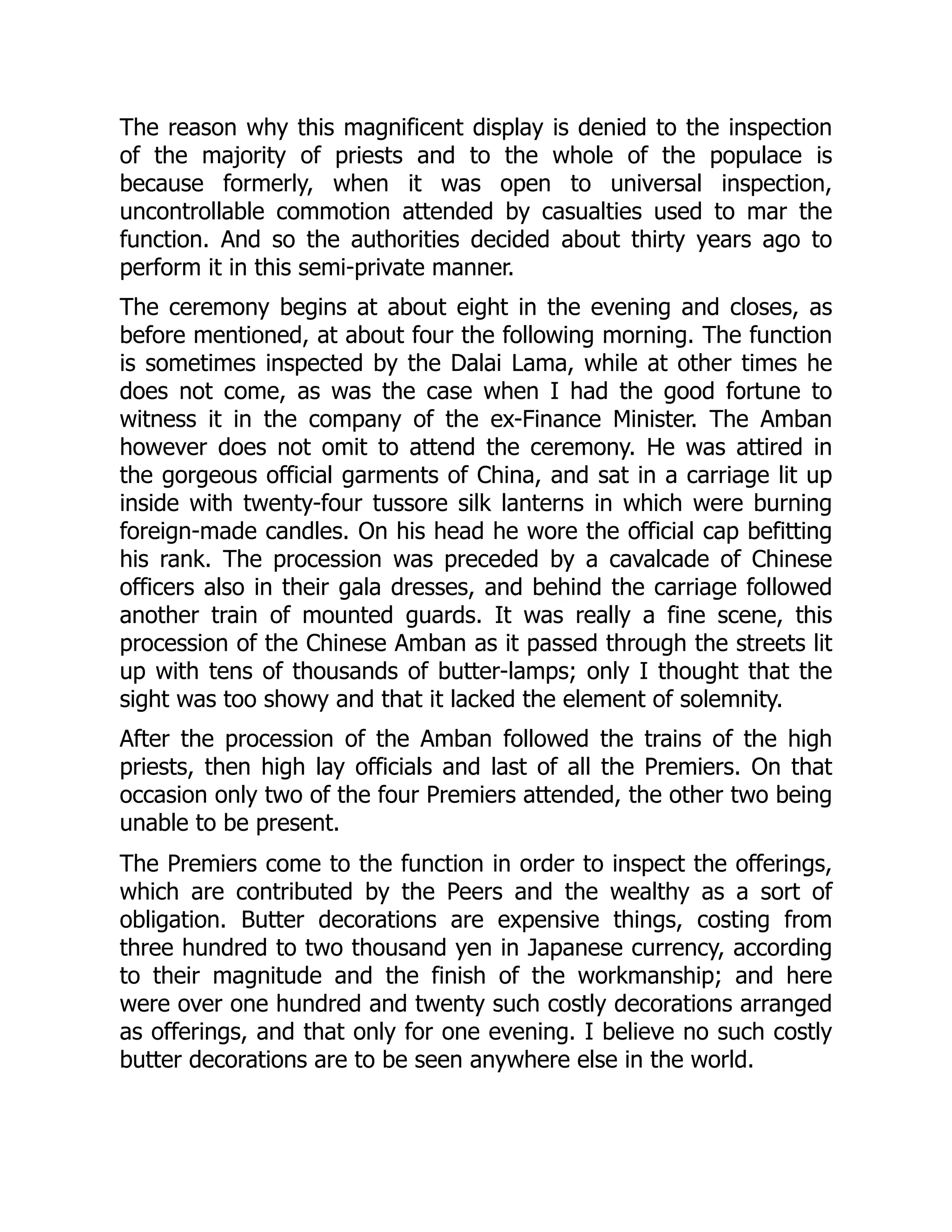

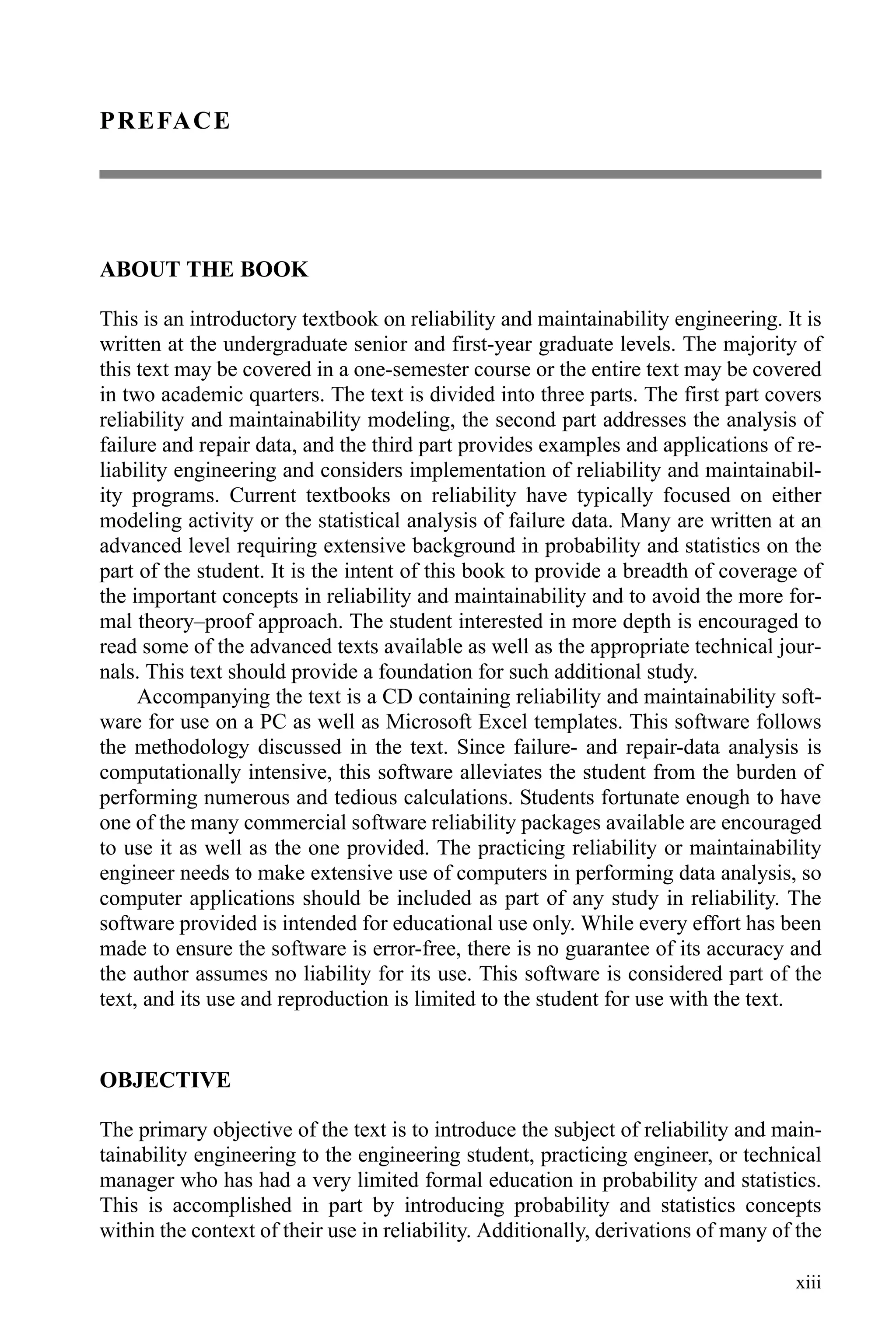

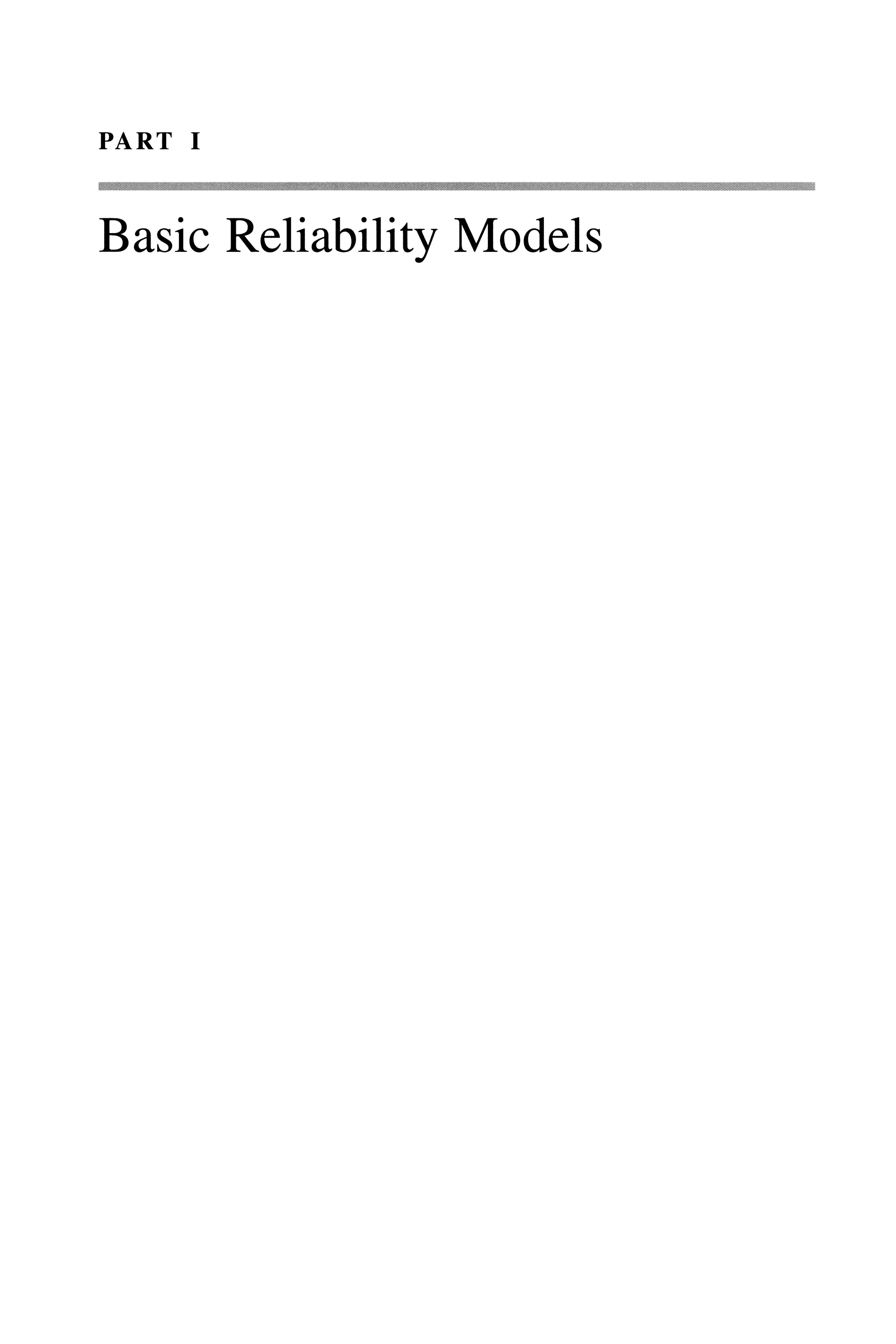

EXAMPLE 1.3. A continuous-flow production line requires a product to be processed

sequentially on 10 different machines. When a machine breaks down, the entire line

must be stopped until the failure is repaired. The average downtime of the line is 12 hr.

This includes time spent waiting for parts and maintenance personnel as well as time

spent troubleshooting and fixing the failed machine. Machine specifications require a

0.99 reliability for each machine over an 8-hr production run. Therefore the reliability of

the production line over an 8-hr run is 0.9910 = 90 percent.4 Assuming a constant failure

rate (exponential failure distribution), this is equivalent to a mean time between failures

(MTBF) of 75.9 operating hours, found by solving the following for MTBF: R(8) =

e-8IMTBF = 0.90, where R(8) is the production line reliability over an 8-hr period.

Under fairly general conditions the steady-state availability of a system is given by

MTBF

A = MTBF + MTTR

where MTTR = the mean time to repair. Therefore, the steady-state availability of the

production line is currently 75.9/(75.9 +12) = 0.86. In order to meet production quotas,

the line must maintain at least a 0.92 availability. Since improvements in machine reli-

ability above 0.99 did not appear feasible, the company decided to increase availability

by improving the maintainability (i.e., decreasing the MTTR).

A minimum MTTR is obtained from Fig. 1.3 or by solving the availability formula

75.9/(75.9 + x) = 0.92 for x: x = 6.6 hr.

By hiring an additional maintenance person, increasing machine spare parts inven-

tory, relocating the inventory closer to the production line, improving diagnostic pro-

cedures, and simplifying the removal and replacement of high-failure components, the

company was able to reduce the MTTR to under 6 hr and achieve the desired availability

goal.

.:s

:g

1.00

0.95

~ 0.90

~

~

>, 0.85

]

CIl

0.80

6.6

0.75 L---'_---'-_--'--_-'-_--'--'-.L.-_L---'_---'-_--'--_-'-_--'----'

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14

Mean time to repair

FIGURE 1.3

Availability of the production line.

4The logic of computing a system reliability for serial units is discussed in Chapter 5.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/60222-250303060215-7ac13b08/75/An-introdution-to-reliability-and-maintainability-engineering-2nd-ed-Edition-Ebeling-30-2048.jpg)

![10 An Introduction to Reliability and Maintainability Engineering

1.4

A BRIEF HISTORY

Early foundations of reliability5 may be found in actuarial concepts used in the

insurance industry, particularly in the study of human survival probabilities. In

the late 1930s and 1940s Weibull analyzed fatigue life in materials, leading to

the probability distribution bearing his name. The study of structural reliability

and fatigue failure began in the 1930s and has since continued. Although early

(l930s and 1940s) development in such areas as queuing and renewal theory,

particularly with the use of the exponential distribution, provided some of the

mathematical foundations of reliability, it was not until after World War II that

reliability became a subject of study. This came about because of the relatively

complex electronic equipment used during the war and the rather high failure

rates observed. In particular, vacuum tubes were notoriously unreliable.

Following the war, Aeronautical Radio, Inc. (ARINC) was established by

commercial airlines to improve airborne electronic equipment (referred to as

avionics by the military). In 1950 the U.S. Air Force formed an ad hoc group to

improve general equipment reliability, and in 1952 the Defense Department

established the Advisory Group on Reliability of Electronic Equipment

(AGREE). The requirement of reliability testing and demonstration of new

systems emerged from this advisory group.

Work published during the 1950s centered around the use of the exponential

distribution to represent failure times, although interest in and the importance of

the Weibull distribution increased by the end of the decade. Initial textbooks on

reliability include Bazovsky [1961] and Barlow and Proschan [1967]. These were

followed by Smith [1976] and Kapur and Lamberson [1977]; the latter book is

still popular today. During the 1970s focus shifted to fault tree analysis, largely

because of concern about nuclear reactor safety. Progressing into the 1980s,

reliability networks received considerable attention in the literature. Both

reliability and maintainability received renewed emphasis in the mid-1980s with

the introduction of the Air Force's Reliability and Maintainability (R&M) 2000

program. Objectives of the R&M 2000 program were to increase system

readiness and availability and to reduce maintenance personnel requirements and

life-cycle costs through increased reliability and maintainability by the year 2000.

Since the turn of the century, much of the research in reliability has

transitioned from the military to industry and academia. This is particularly true

with regard to automotive manufacturers and their suppliers, who have had to

compete in the world market with increasingly reliable vehicles. To participate in

a global economy, companies must consider product reliability as a primary

concern. More universities are teaching reliability and faculty research and

publications on reliability have seen steady growth. Perhaps the most significant

development in reliability research has been the increased availability of

reliability data in electronic format. Today, there is little reason for a company

5Students interested in more detail about the development ofreliability are encouraged to read "Mathematical

Theory of Reliability: A Historical Perspective,'· by Barlow [1984].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/60222-250303060215-7ac13b08/75/An-introdution-to-reliability-and-maintainability-engineering-2nd-ed-Edition-Ebeling-31-2048.jpg)

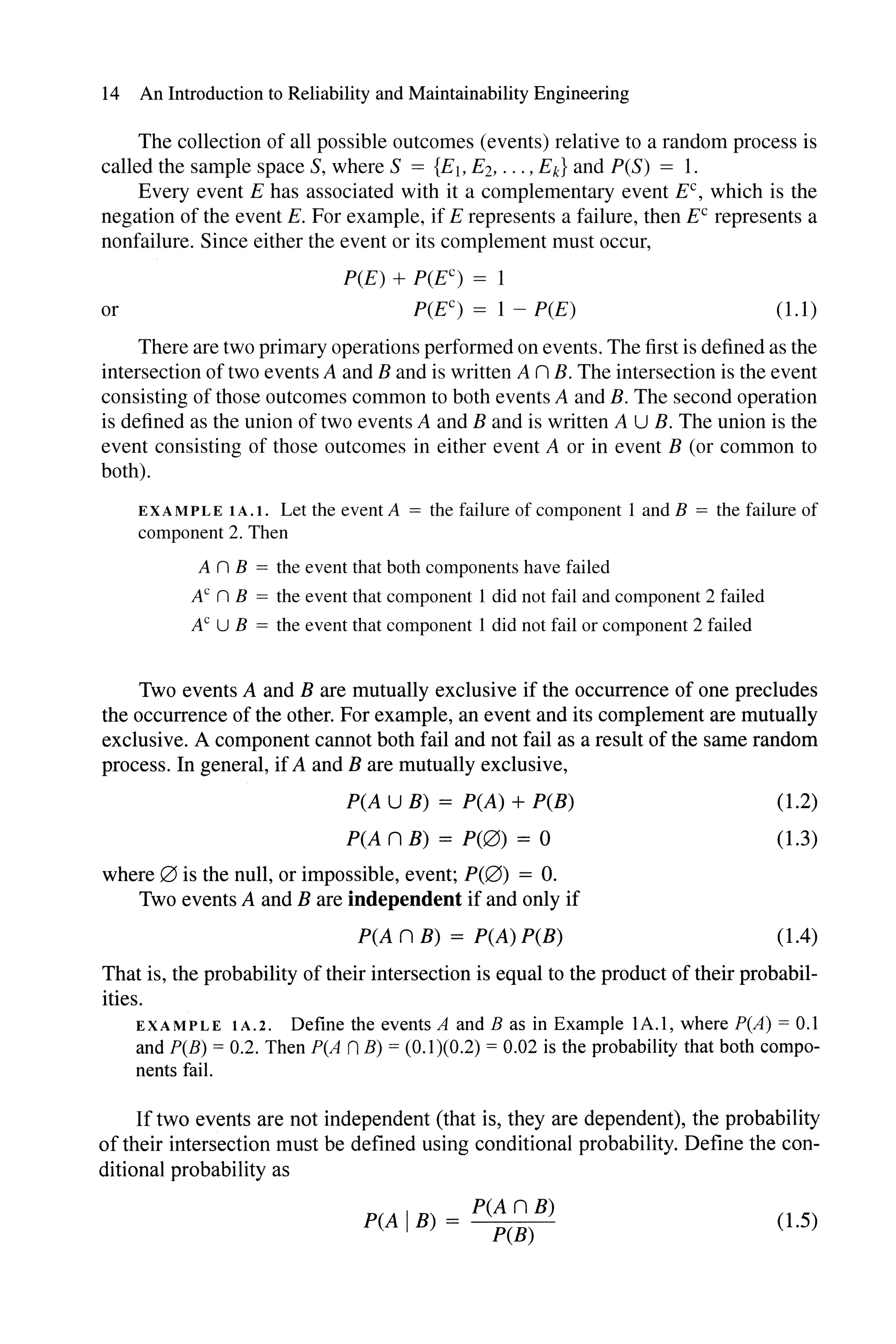

![CHAPTER 1: Introduction 13

be selected from among those models discussed in Part I. This requires

estimation of the distribution parameters, discussed in Chapter 15, and a

statistical goodness-of-fit test, discussed in Chapter 16, to either reject or not

reject the hypothesized distribution. From the material presented in Part II, the

reliability engineer should be able to establish a test plan, collect failure or repair

data, and complete a statistical analysis of the data, resulting in an acceptable

Part III, "Application," concludes the development of reliability engineering

by presenting several applications in Chapter 17 and by identifying policies,

procedures, issues, and concerns in implementing a reliability program in

Chapter 18. Together, these last two chapters attempt to integrate the material

from Parts I and II.

Other introductory texts on reliability include Bain and Engelhardt [1991],

Blanks [1992], Bunday [1991], Crowder et al. [1991], Dai and Wang [1992],

Elsayed [1996], Grosh [1989], Kales [1998], Kececioglu [1991], Leemis [1995],

Ramakumar [1993], Rao [1992], Sundararajan [1991], Todinov [2005], and

Zacks [1992].

APPENDIX IA

A PROBABILITY PRIMER

There are two general approaches to modeling uncertainty by using probability con-

cepts. The more basic method makes use of the idea of a sample space and events

defined over the sample space. It then defines the probability of these events and

computes probabilities of more complex events formed from unions and intersec-

tions of elementary events. The second method is based on the concept of a random

variable and a probability distribution associated with the random variable. A ran-

dom variable is a variable that takes on certain values in accordance with specified

probabilities. By specifying the probability distribution of a random variable, we can

completely characterize the random process. We will have occasion throughout this

text to utilize both methods. For example, we may define an event to be a component

failure and a random variable to be the time to failure of the same component.

IA.I

RANDOM EVENTS

In reliability engineering a failure can be described as a random event. A random

event E will occur with some probability denoted by peE) where 0 :s; peE) :s; 1.

peE) = 0 describes an impossible event, and peE) = 1denotes a certain event. The

closer peE) is to 1, the more likely it is that the event (e.g., failure) will occur.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/60222-250303060215-7ac13b08/75/An-introdution-to-reliability-and-maintainability-engineering-2nd-ed-Edition-Ebeling-34-2048.jpg)

![16 An Introduction to Reliability and Maintainability Engineering

1 - 0.005 = 0.995, which is the probability that at least one ofthe two components does

not fail.

lA.2

BAYES' FORMULA

Bayes' formula involves conditional probabilities of two events. It can be derived

by observing that

p(AnB) p(BnA)

peA IB) = PCB) = P[(B n A) U (B n N)]

PCB IA)P(A)

PCB IA)P(A) + PCB IN)P(AC)

where the events B n A and B n AC are mutually exclusive.

(LlO)

EXAMPLE lA.6. A smoke detector is routinely inspected. Eighty percent of the detec-

tors found inoperative had experienced a power surge, and 10 percent of those found

in operating condition had experienced a power surge. Twenty percent of the detectors

inspected have failed. What is the probability of a detector failing given it experiences

a power surge?

Solution. LetA = the event that a detector has failed and B = the event that the detector

had experienced a power surge. Then peA) = 0.20, PCB IA) = 0.80, and PCB IAC) =

0.10. Therefore

peA IB) (0.80)(0.20) = 0.16 = 0667

= (0.80)(0.20) + (0.10)(0.80) 0.24 .

Bayes' formula is generalized as follows:

i = 1, ... , n (1.11)

where the events Ai, i = 1, ... , n, form a partition. That is, they are mutually exclu-

sive and their intersection comprises the entire sample space (they are collectively

exhaustive). As a result the denominator in Eq. (1.11) is equal to P(B).

lA.3

RANDOM VARIABLES

Although the concept of a random event is a useful one in describing random pro-

cesses, a more useful concept is that of a random variable. A random variable is a

variable that takes on numerical values in accordance with some probability dis-

tribution. Random variables may be either continuous (taking on real numbers)

or discrete (usually taking on nonnegative integer values). The probability dis-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/60222-250303060215-7ac13b08/75/An-introdution-to-reliability-and-maintainability-engineering-2nd-ed-Edition-Ebeling-37-2048.jpg)

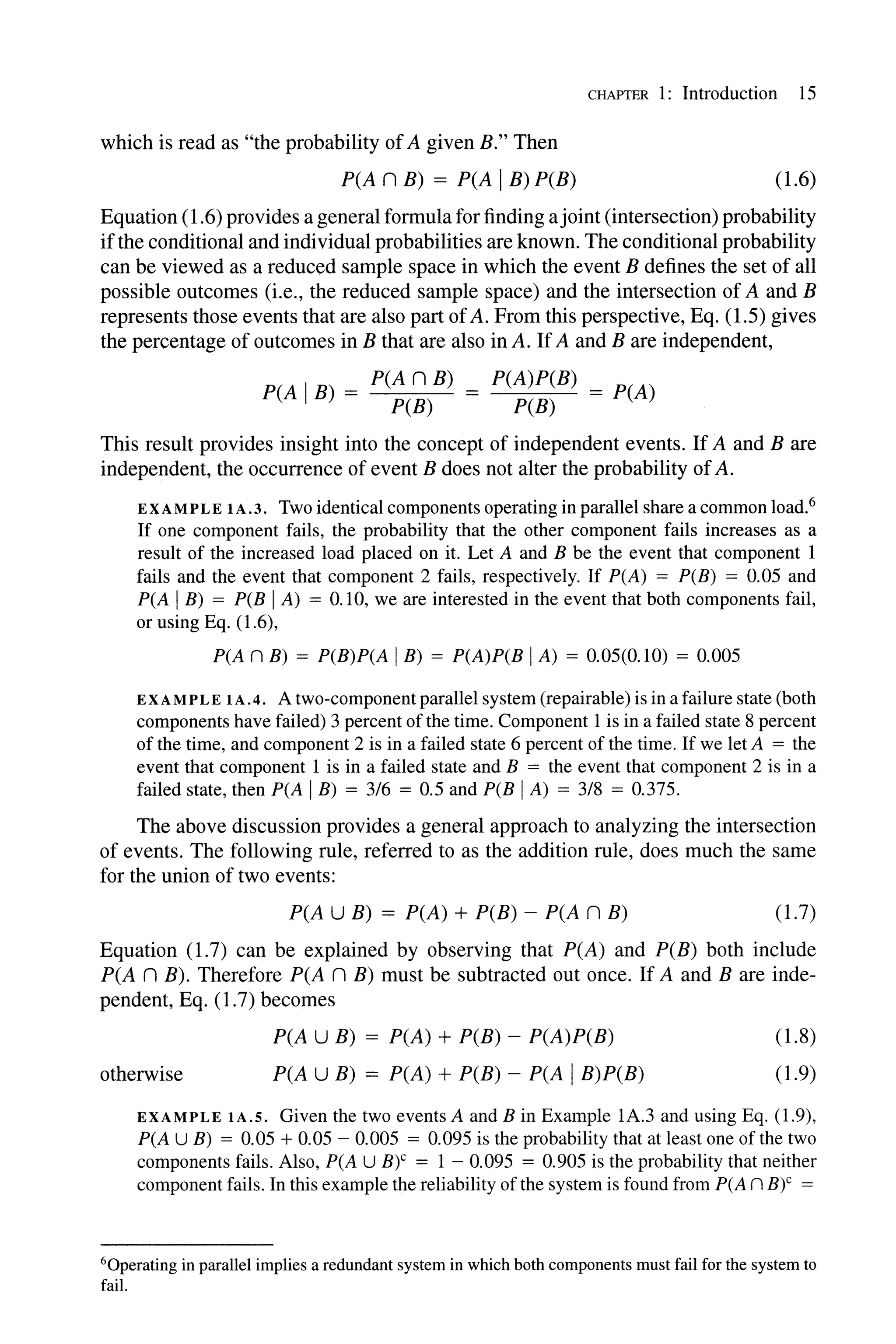

![CHAPTER 1: Introduction 19

lA.7

CONTINUOUS DISTRIBUTIONS

The following relations hold for any continuous probability distribution:

1. 0 :5 F(x) :5 1

x

2. Pr{X :5 x} = F(x) = If({) d{

3. f(x) = d~~x)

00

4. I f(x)dx = 1

-00

b

5. Pr{a:5 X :5 b} = If(x)dx = F(b) - F(a)

a

00

6. E(X) = JL = Ixf(x)dx

-00

where JL is the mean or expected value of the random variable X.

00

7. Var(X) = u 2 = I(x - JL)2 f(x)dx

where u 2 is the variance of the distribution.

(1.17)

(1.18)

(1.19)

(1.20)

(1.21)

(1.22)

8. If Y = L.7=1 aiXi where the Xi are independent random variables having means

JLi and variances uf and the ai are constants, then

n

E(Y) = 2:aiJLi

i= 1

and

n

Var(Y) = 2:afuf (1.23)

i= 1

In general we may describe the distribution of a random variable in terms of its

PDF, f(x), or its CDF, F(x). Although a random variable may be defined over the

open interval (-00,00), when the random variable represents a failure time or repair

time, only nonnegative values are permitted. Therefore the domain of the random

variable would normally be [0, 00), and the lower limits of the integrals in relations

2, 4, 6, and 7 would reflect this change. The concepts ofrandom variables and proba-

bility distributions are explored more fully in the next several chapters as the failure

probability distribution is developed as the primary focus ofPart I. Examples ofthese

distributions will therefore be presented in the context of their use in developing re-

liability models. More detailed coverage of probability theory may be found in Ross

[1987].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/60222-250303060215-7ac13b08/75/An-introdution-to-reliability-and-maintainability-engineering-2nd-ed-Edition-Ebeling-40-2048.jpg)

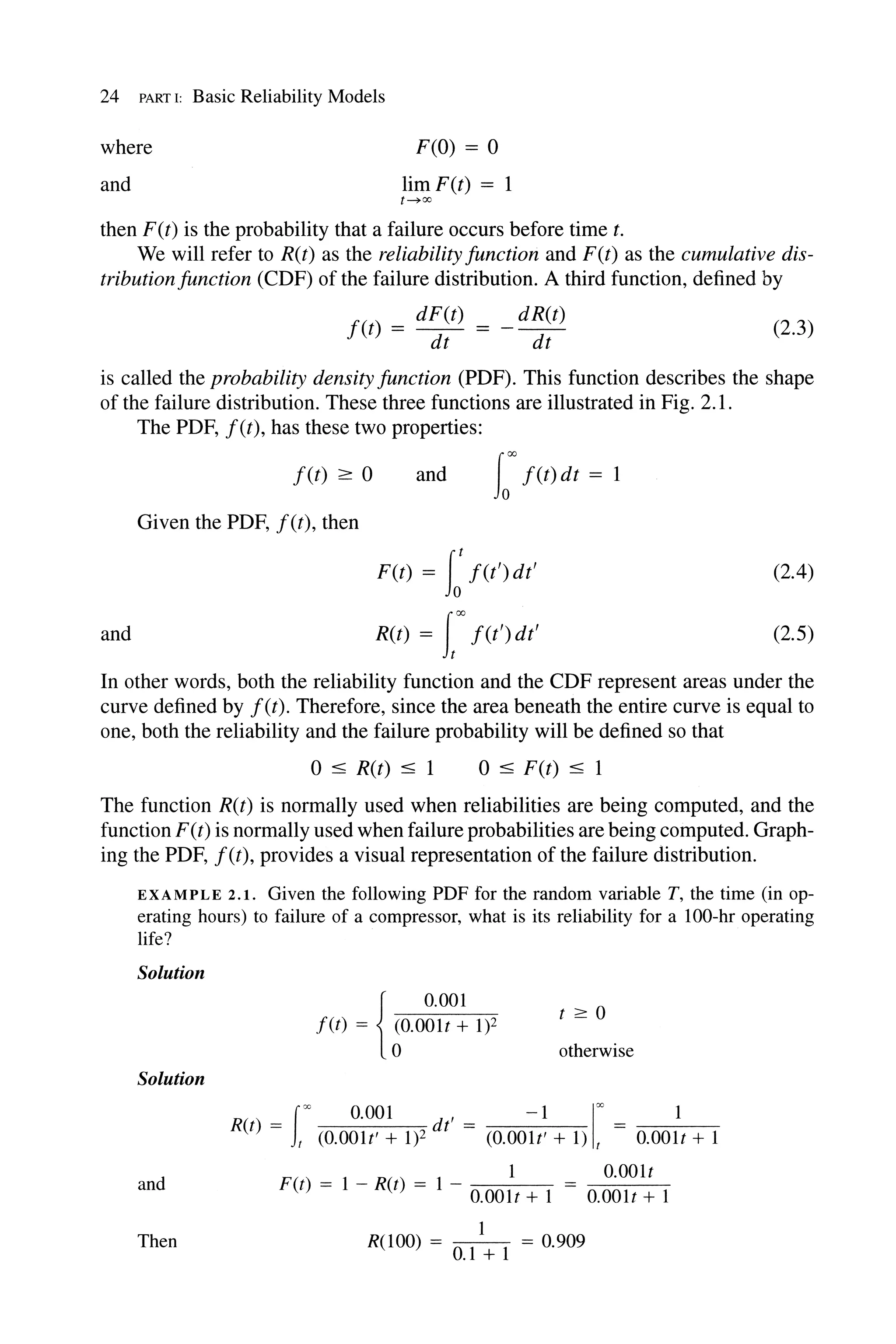

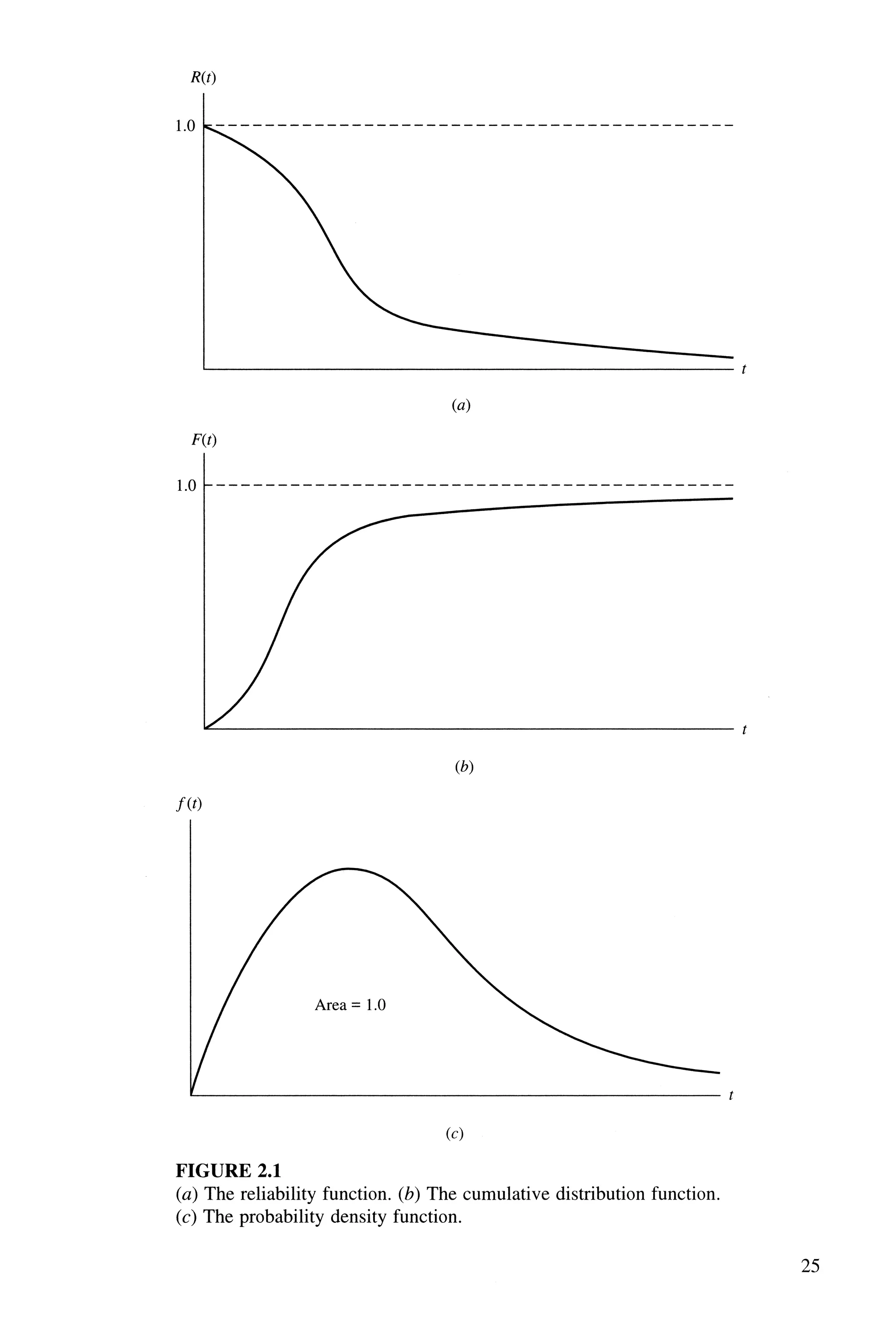

![26 PART I: Basic Reliability Models

A design life is defined to be the time to failure tR that corresponds to a specified reliabil-

ity R. That is R(tR) = R. To find the design life if a reliability of 0.95 is desired, we set

1

R(t ) = 0.95

R O.OOltR +1

Solving for tct,

tR =1000(0.~5 -1)= 52.6hr

The probability of a failure occurring within some interval of time [a, b] may be

found using any of the three probability functions, since

Pr{ a :::; T :::; b} = F(b) - F(a) = R(a) - R(b) = rf(t)dt (2.6)

From the previous example,

1 1

Pr{ 10 :::; T :::; 100} = R(10) - R(100) = 0.01 + 1 - 0.1 + 1 = 0.081

2.2

MEAN TIME TO FAILURE

The mean time to failure (MTTF) is defined by

MTTF = E(T) = fo'''' tf(t)dt (2.7)

which is the mean, or expected value, of the probability distribution defined by f(t).

It can also be shown (Appendix 2A) that

MTTF = fo'''' R(t) dt (2.8)

Equation (2.8) is often easier to apply than (2.7).

The mean of the failure distribution is only one of several measures of central

tendency of the failure distribution. Another is the median time to failure, defined by

R(tmed) = 0.5 = Pr{ T 2: tmed} (2.9)

The median divides the distribution into two halves, with 50 percent of the fail-

ures occurring before the median time to failure and 50 percent occurring after the

median. The median may be preferred to the mean when the distribution is highly

skewed.

A third frequently used average is the mode, or most likely observed failure

time, defined by

f(tmode) = max f(t)

O:s«oo

(2.10)

For a small fixed interval of time centered around the mode, the probability offailure

will generally be greater than for an interval of the same size located elsewhere

within the distribution. Figure 2.2 shows the locations of the mean, the median, and

the mode for a distribution skewed to the right.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/60222-250303060215-7ac13b08/75/An-introdution-to-reliability-and-maintainability-engineering-2nd-ed-Edition-Ebeling-47-2048.jpg)

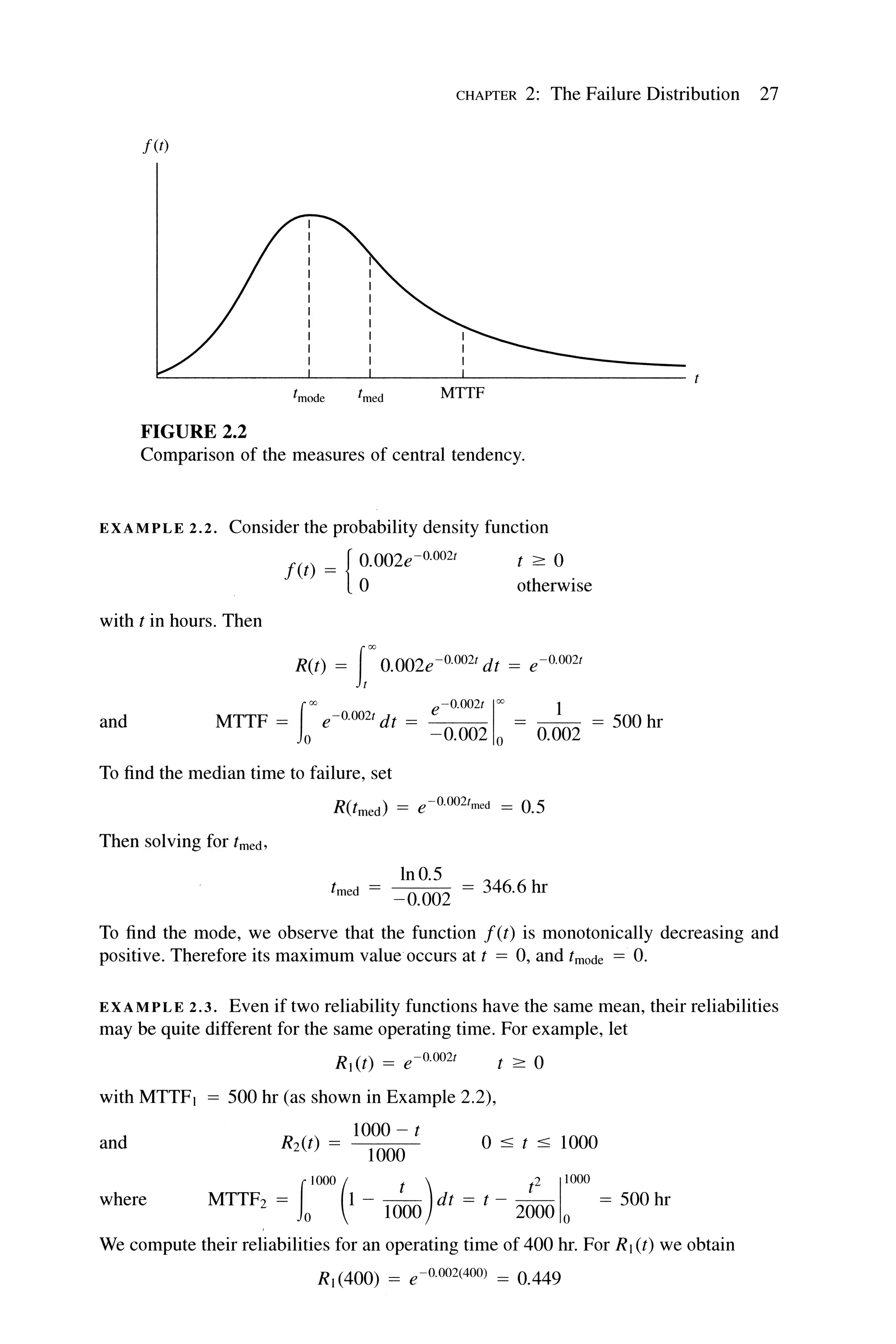

![Then

CHAPTER 2: The Failure Distribution 29

Pr{t :::; T :::; t + !It IT;::: t} = _R-,-(t,---)---=-R-,-:,(t_+_L1....:...t)

R(t)

R(t) - R(t + L1t)

R(t) L1t

is the conditional probability of failure per unit of time (failure rate).

Set

A(t) = lim -[R(t + L1t) - R(t)] . _1_

~t-+O !It R(t)

-dR(t) 1 f(t)

-----:d:--t:....:... . -R(-t) = -R(-t)

(2.13)

Then A(t) is known as the instantaneous hazard rate or failure rate function. The

failure rate function A(t) provides an alternative way of describing a failure distribu-

tion. Failure rates in some cases may be characterized as increasing (IFR), decreas-

ing (DFR), or constant (CFR) when A(t) is an increasing, decreasing, or constant

function.

A particular hazard rate function will uniquely determine a reliability function.

To see this, let

A(t) = -dR(t) . _1_

dt R(t)

or ( )d = -dR(t)

1 t t R(t)

Integrating,

(t , , _ IR(t) -dR(t')

Jo A(t ) dt - 1 R(t')

where R(O) = 1 establishes the lower limit in the integral on the right-hand side.

Then

-I:A(t') dt' = In R(t)

or R(t) = exp [- I:A(t')dt'] (2.14)

Equation (2.14) can then be used to derive the reliability function from a known

hazard rate function.

EXAMPLE 2.5. Given the linear hazard rate function A(t) = 5 x 1O-6t where t is mea-

sured in operating hours, what is the design life if a 0.98 reliability is desired?

Solution](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/60222-250303060215-7ac13b08/75/An-introdution-to-reliability-and-maintainability-engineering-2nd-ed-Edition-Ebeling-50-2048.jpg)