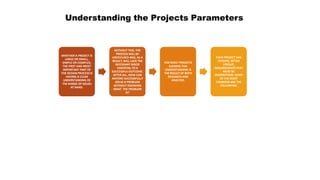

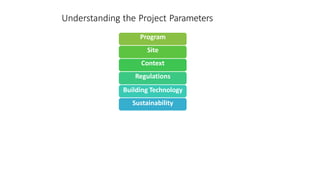

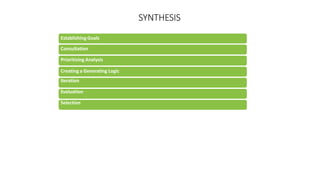

The document discusses the essential components of managing an architectural project, emphasizing the importance of project management principles applicable to various scales of work. It outlines the project manager's responsibilities, the necessary organizational tools, and the design process, highlighting the need for a structured approach towards understanding client requirements and project parameters. Additionally, it describes the contractual framework governing these projects, detailing the phases from design to construction administration.