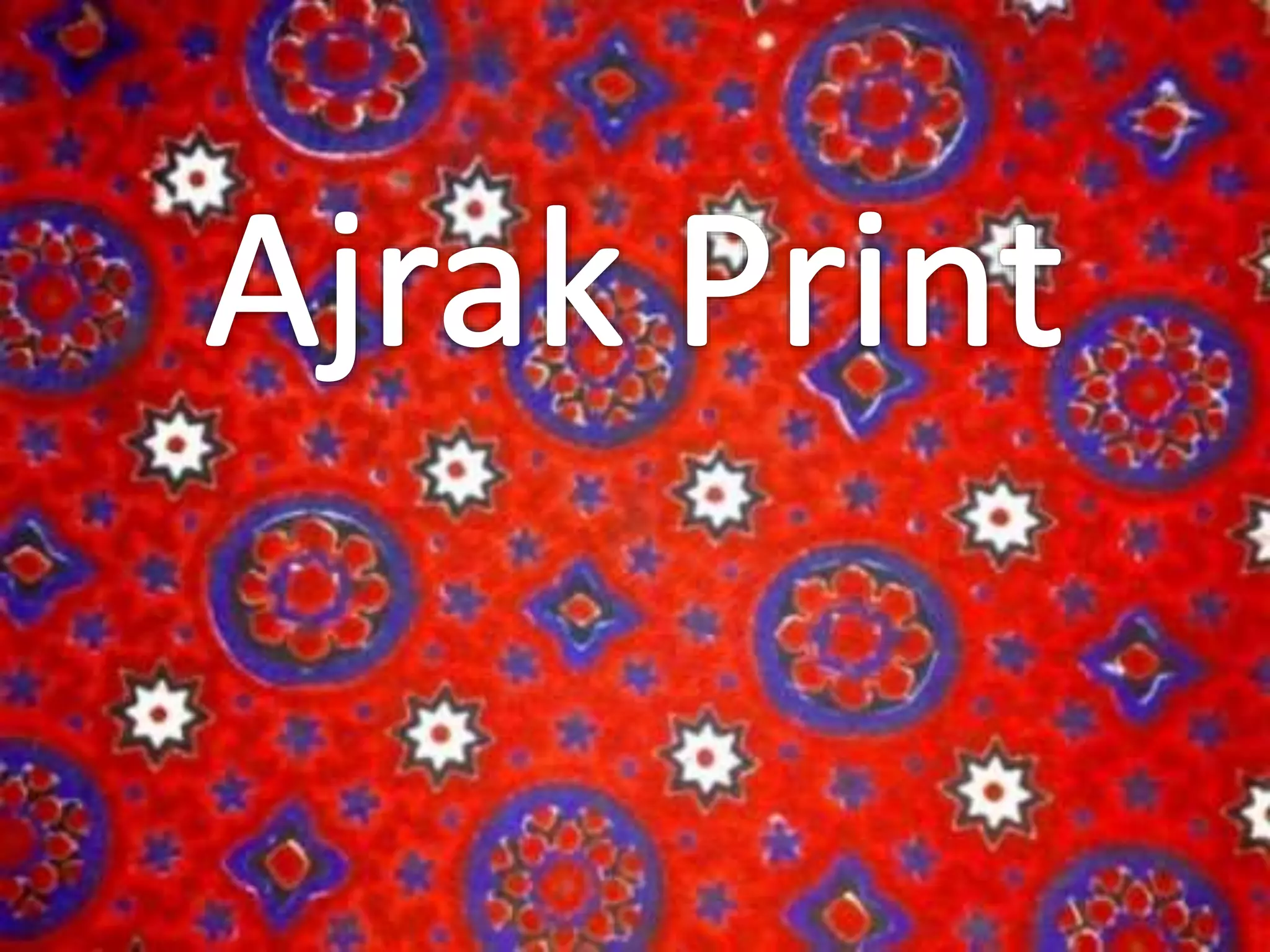

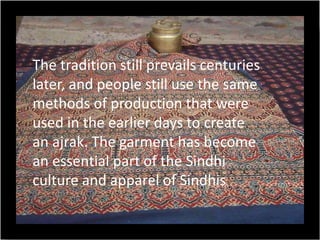

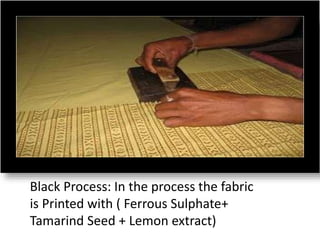

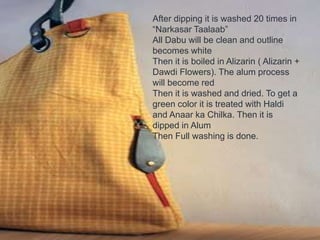

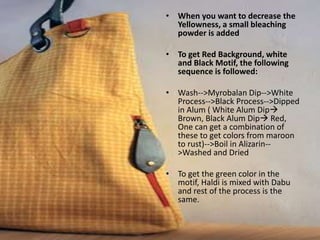

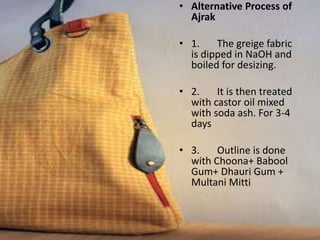

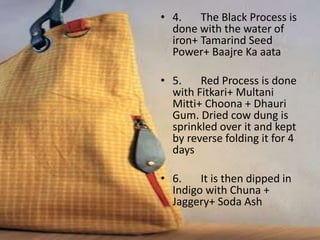

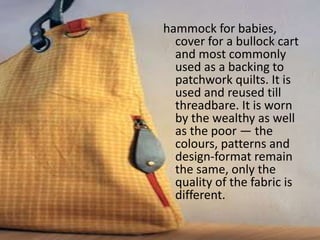

The traditional craft of Ajrakh block printing has reached great heights of excellence in Ballotra, Rajasthan, due to the availability of good water needed for the hand printing process. Ajrakh printing involves laboriously block printing both sides of the fabric simultaneously using natural dyes in a resist dyeing technique. This makes the hand-printed fabric from Ballotra very exclusive and expensive. Ajrakh printing is one of the oldest block printing techniques still practiced in parts of Gujarat and Rajasthan in India and Sindh in Pakistan.