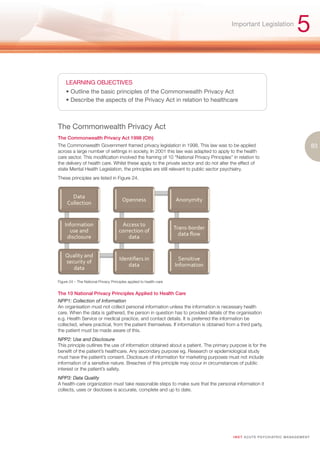

The document is a comprehensive guide for junior doctors on managing acute psychiatric conditions, focusing on assessment, treatment, and management challenges. It provides insights into risk assessment, treatment options, and the complexities of psychiatric care within the New South Wales public health system. The resource aims to equip psychiatric trainees with essential knowledge and practical approaches to care for patients in acute mental health settings.

![Long-term impairment of psychosocial and interpersonal functioning

The prospect of chronic psychosocial disability relates to both factors in the illness and the

experience of stigma by those suffering mental illness. Wing and Morris (1981) defined this

phenomenon as “secondary disability” building upon the primary disability of the disorder itself.

Such disability extends from the experience of the illness, in particular “adverse personal reactions”

by those around the patient. Tertiary disabilities arise from the “social disablements” borne of broad

community responses to people with mental illness.16

The notion of stigma is relevant to this process. Stigma, meaning ‘mark’ alludes to the process

in which a person with a mental illness is ‘marked’ as different from others by that illness. Erving

Goffman described stigma in relation to mental illness as a process of “spoiled identity”.17 One

study found stigma as having multiple components – ‘social distance’, ‘dangerous/unpredictable’,

10 ‘weak not sick’, ‘stigma perceived in others’ and ‘reluctance to disclose’.18 Despite recent efforts at

educating the public about the stigma of mental illness, perceptions of the mentally remain in the

realm of “psychokiller/maniac”, “indulgent”, “libidinous”, “pathetic and sad” and “dishonest hiding

behind ‘psychobabble’ or doctors”.19 A survey by SANE Australia found that 76% of consumers and

carers experienced stigma at least every few months. Moreover, virtually all people suffering from

mental illness believe that negative portrayals of mental illness in the media had a negative effect, in

particular, “self-stigma”.20 The portrayal of mental illness in the media often reflects and perpetuates

the myths and misunderstandings associated with mental illness.21 So severe is the problem, that

the World Health Organization and the World Psychiatric Association have identified stigma related

to mental illness as the most significant challenge.22

The experience of stigma manifests as the propensity of a person with a mental illness to have lower

expectations of themselves and their lives, this is particularly the case in seeking employment in

an open market.23 Indeed, unemployment rates for people with serious and persistent psychiatric

disabilities are typically 80-90%.24 Prospective employers are frequently reluctant to hire someone

with past psychiatric history or currently undergoing treatment for depression, and approximately

70% are reluctant to hire someone with a history of substance abuse or someone currently taking

antipsychotic medication.25 The experience of such discrimination leads many people with mental

illness to view themselves as unemployable and stop seeking work altogether.26 Figure 5 provides

an approach for formulating an assessment of a patient whose illness presents risk of psychosocial

disability.

16.

Wing JK, Morris B Handbook of Psychiatric Rehabilitation Practice Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981

17.

Goffman E. 1963 Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Engelwood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall

18.

Jorm A, Wright A. Influences on young people’s stigmatising attitudes towards peers with mental disorders: national survey

of young Australians and their parents. The British Journal of Psychiatry 2008 192: 144-149

19.

Byrne P. Stigma of mental illness and ways of diminishing it. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 2000 6: 65-72

20.

SANE Australia. Make it Real 2005 www.mindframe-media.info/client_images/355550.pdf (accessed April 1 2008)

21.

Hyler SE, Gabbard GO, Schneider I. Homicidal maniacs and narcissistic parasites: Stigmatisation of mentally

ill persons in the movies. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 1991, 42, 1044-1048

22.

Sartorius N. The World Psychiatric Association global programme against stigma and discrimination because of schizophrenia.

In: Crisp AH, editor. Every family in the land [revised edition]. London: Royal Society of Medicine Press; 2004. pp. 373-375

23.

Marrone JF, Follwy S, Selleck V. How mental health and welfare to work interact: the role of hope, sanctions, engagement,

and support. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation 2005; 8:81-101

24.

Crowther RE, Marchall M, Bond GR et al. Helping people with severe mental illness to obtain work: systematic review.

BMJ 2001; 322:204-208

25.

Scheid TL. Employment of individuals with mental disabilities: business response to the ADA’s challenge. Behavioral Sciences

and the Law 1999; 17:73-91

26.

Link B. Mental patient status, work, and income: an examination of the effects of a psychiatric label. American Sociological

Review 1982; 47:202-215](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/acutepsychiatricmanagementnswimet-111016154659-phpapp01/85/Acute-Psychiatric-Management-12-320.jpg)