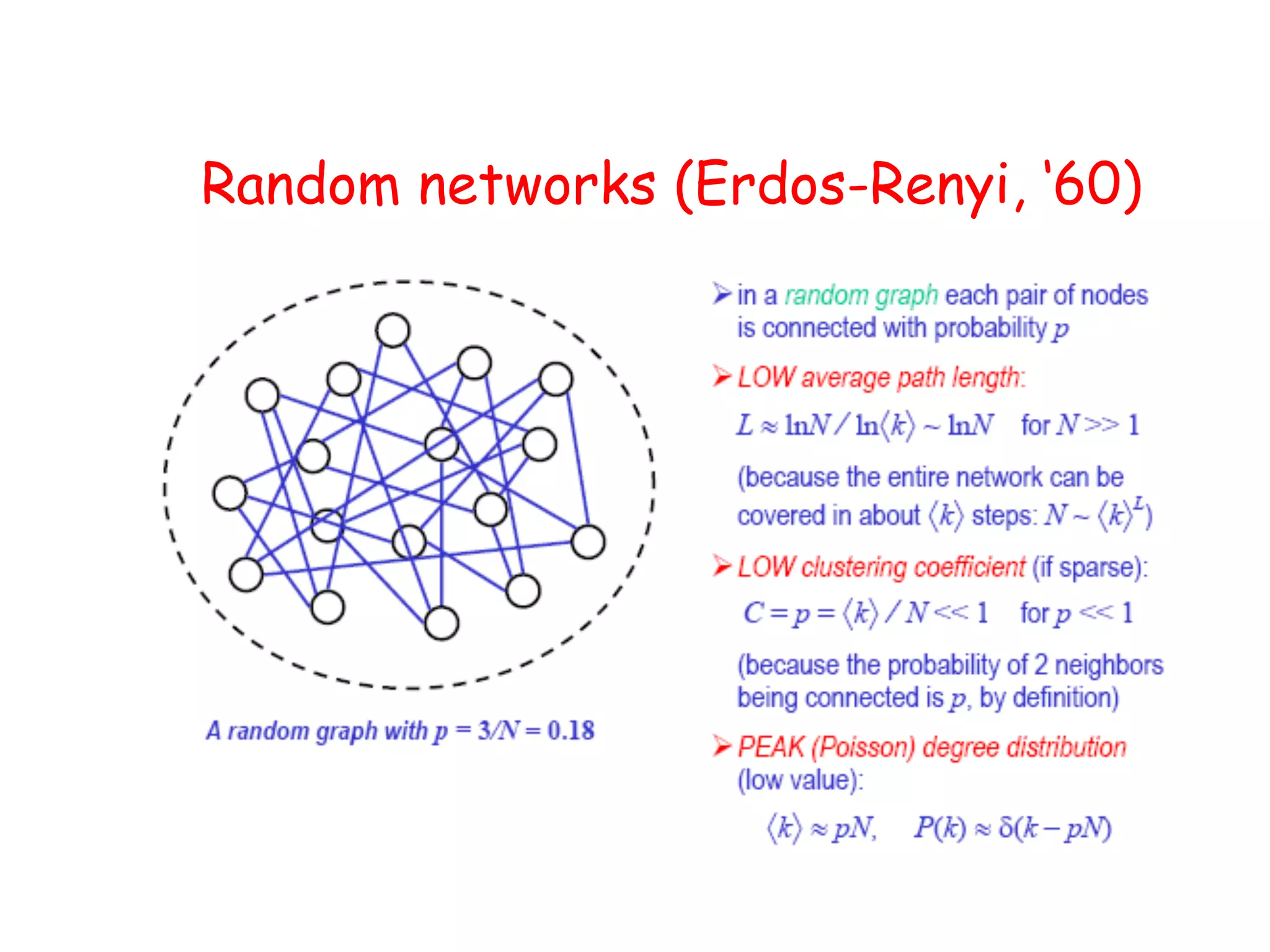

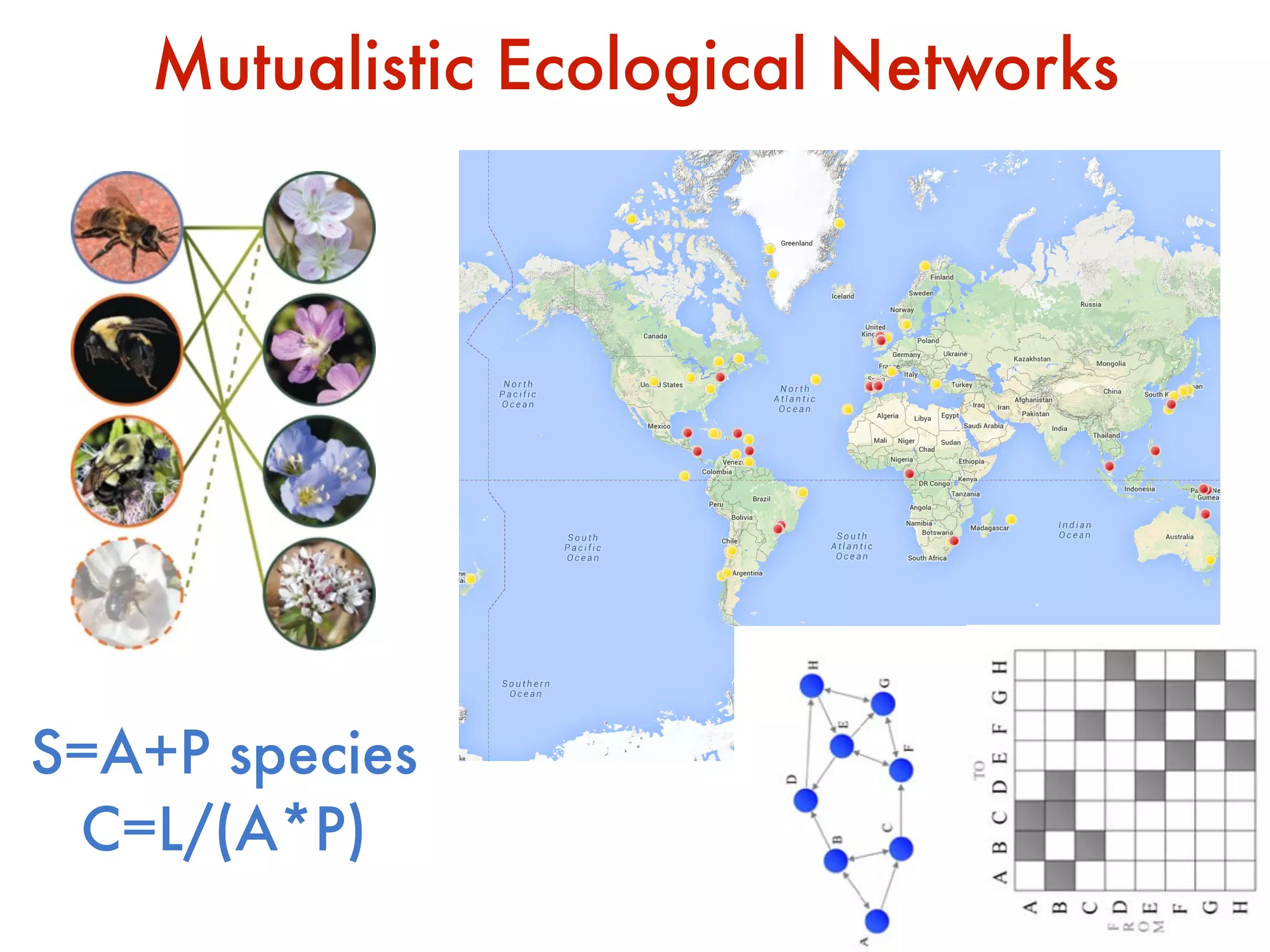

- Systems biology is an interdisciplinary field that studies biological systems using a holistic approach, focusing on complex interactions within systems.

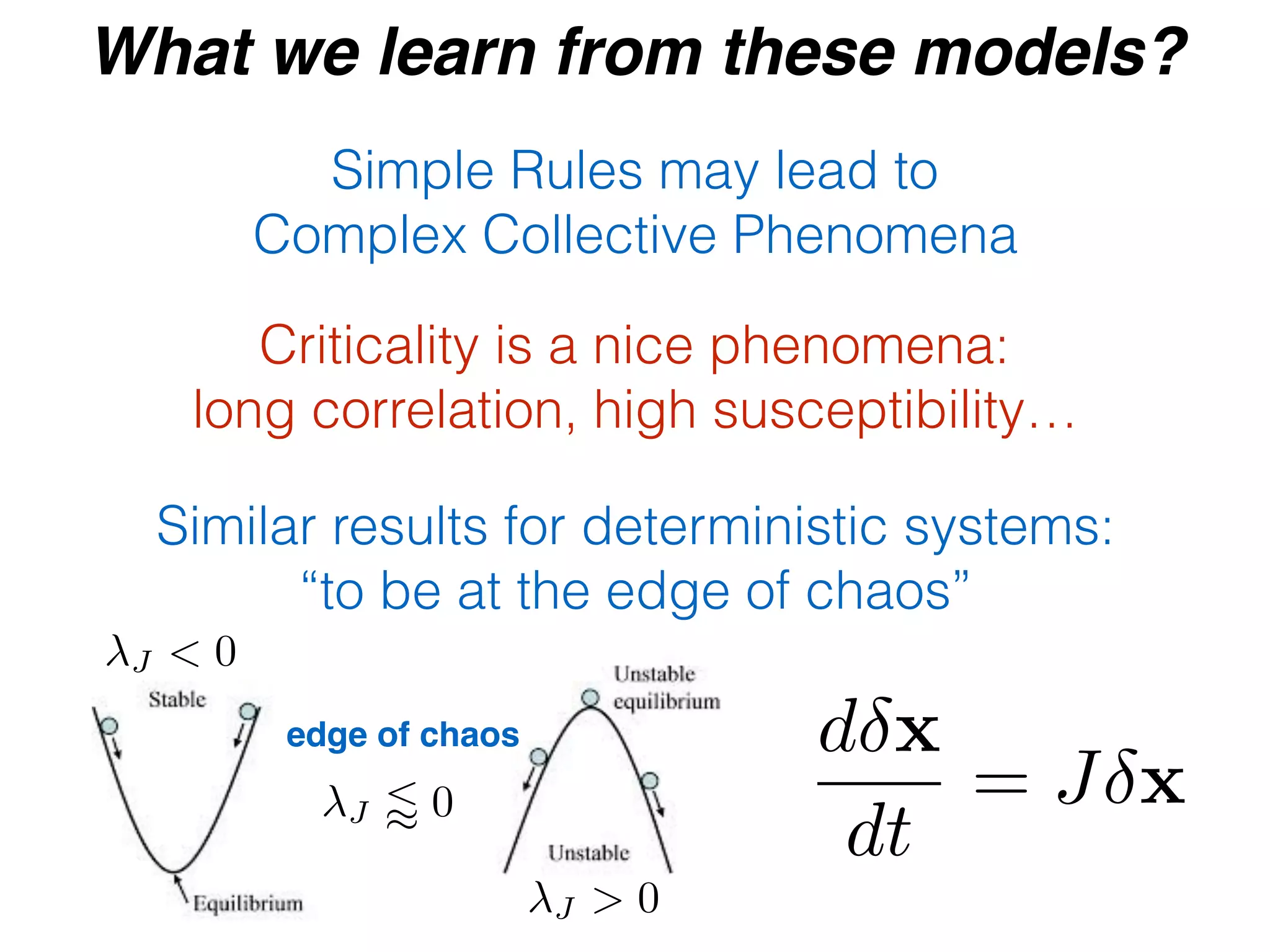

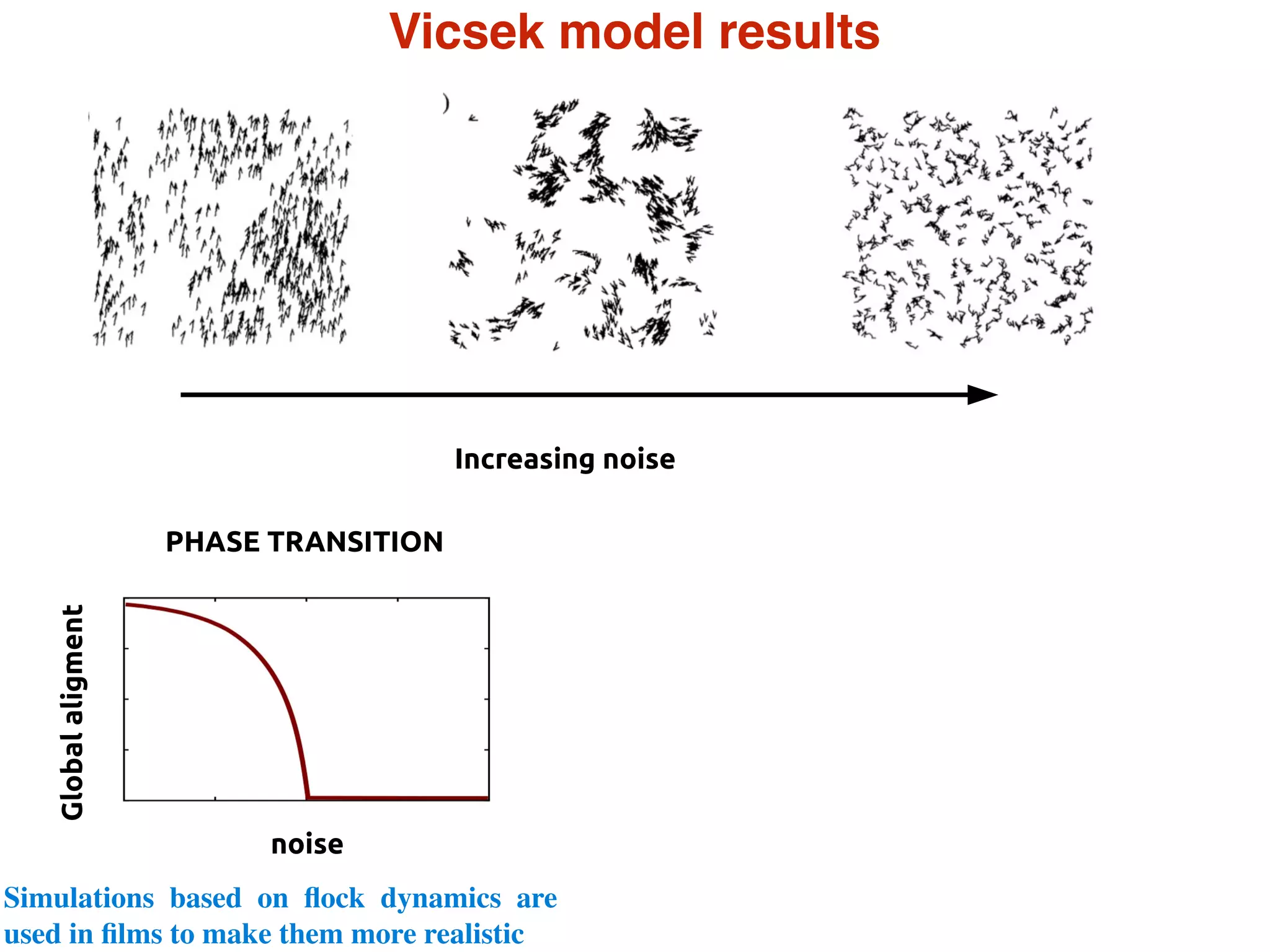

- Statistical physics approaches, like the Ising model of magnetism, can be applied to study biological systems and emergent phenomena. These simple models reveal how complex collective behavior can arise from local interactions.

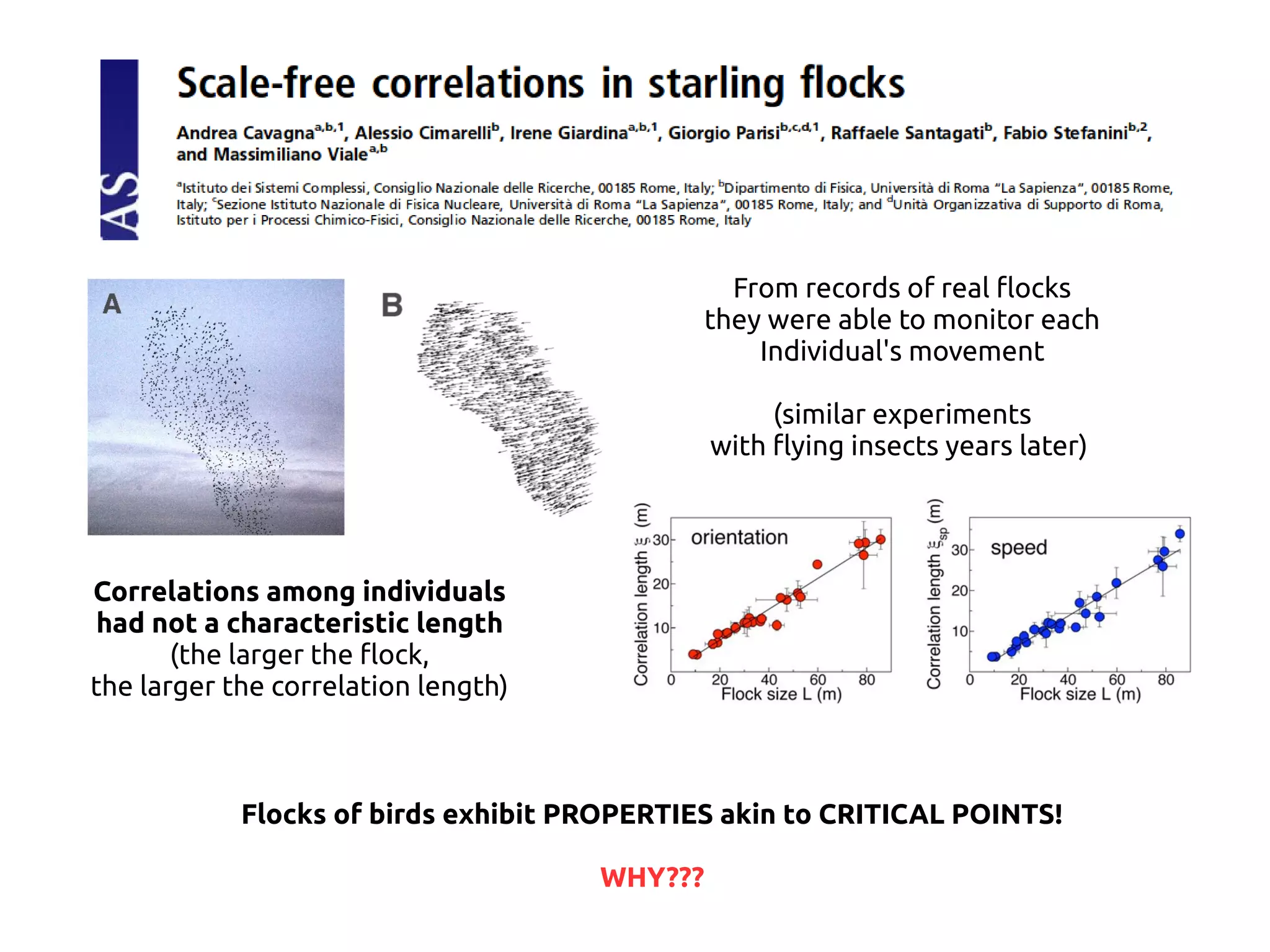

- Critical phenomena observed in models like the Ising model provide insights into how biological systems may benefit from operating near a critical point, with long-range correlations and sensitivity to perturbations.

![ie e viene descritta dalla birth-deah master equation [8], che descrive la probabilità P(n, t)

data specie al tempo t di avere una popolazione di n individui

dP

dt

(n, t) = b(n 1) · P(n 1, t) [b(n) + d(n)] · P(n, t) + d(n + 1) · P(n + 1, t)

e b(n) e d(n) sono rispettivamente i parametri di nascita e morte, dati dalle seguenti

b(n) = (1 n) ·

n

J

J n

J 1

d(n) = (1 n) ·

n

J

J n

J 1

+ n ·

n

J

Notiamo che queste definizioni sono consistenti con le due regole della dinamica del V

del:

con probabilità 1 n si ha la morte di un individuo della comunità non appartenente

specie data (con probabilità J n

J ) accompagnata dalla nascita di un individuo della sp

scelta ( n

J 1 );

con probabiltà n

J si ha la morte di un individuo appartenente alla specie data accompag

ta o dalla migrazione di un individuo proveniente da una delle altre specie presenti

probabilità (1 n)

⇣

J n

J 1

⌘

) o dalla comparsa di una nuova specie (con probabilità n).

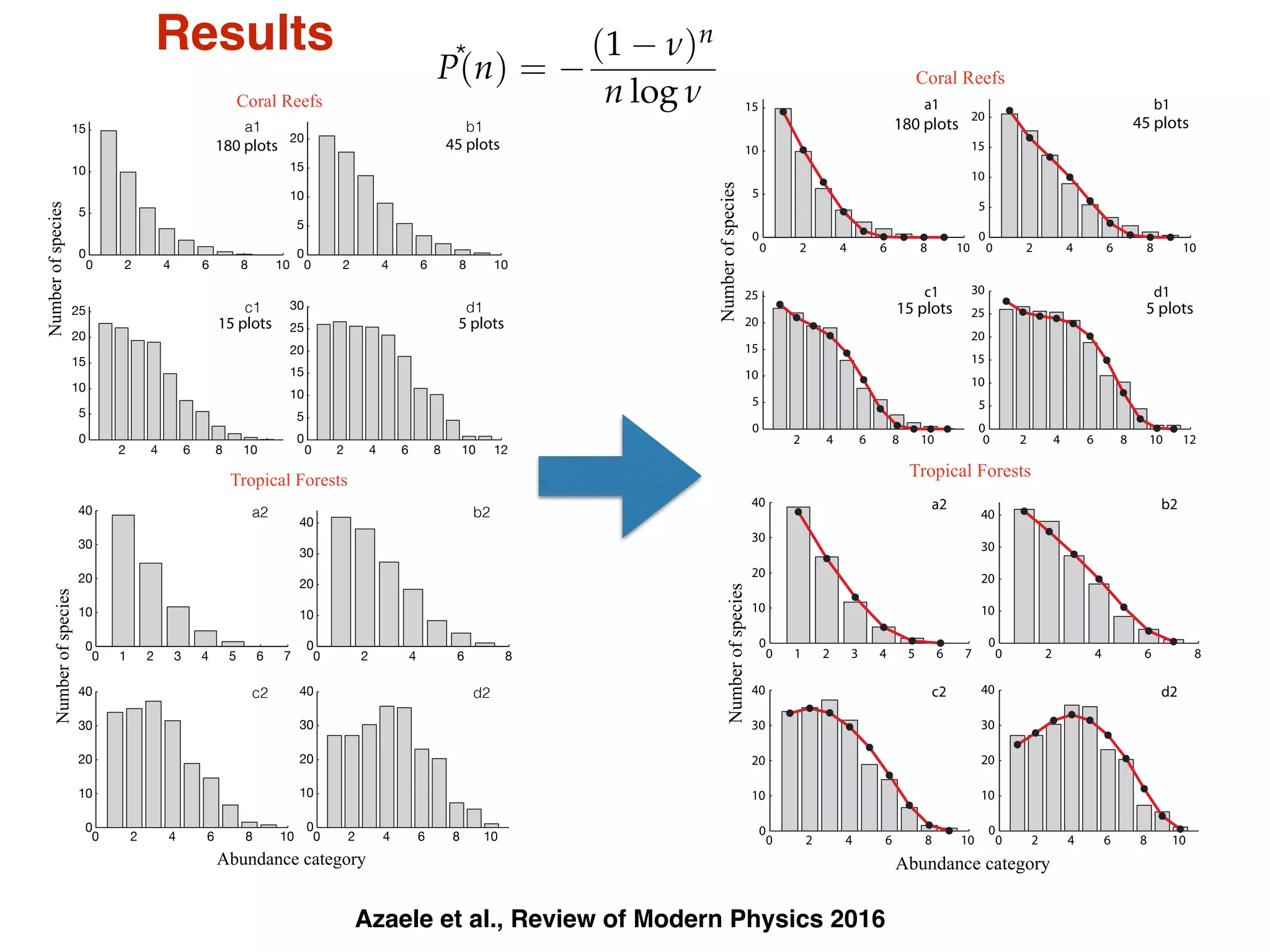

oluzione stazionaria o di equilibrio P⇤(n) per la (3.1) è la seguente [8]

escritta dalla birth-deah master equation [8], che descrive la probabilità P(n, t) per

al tempo t di avere una popolazione di n individui

) = b(n 1) · P(n 1, t) [b(n) + d(n)] · P(n, t) + d(n + 1) · P(n + 1, t) (3.1)

) sono rispettivamente i parametri di nascita e morte, dati dalle seguenti

b(n) = (1 n) ·

n

J

J n

J 1

(3.2)

d(n) = (1 n) ·

n

J

J n

J 1

+ n ·

n

J

(3.3)

e queste definizioni sono consistenti con le due regole della dinamica del Voter

bilità 1 n si ha la morte di un individuo della comunità non appartenente alla

a (con probabilità J n

J ) accompagnata dalla nascita di un individuo della specie

);

biltà n

J si ha la morte di un individuo appartenente alla specie data accompagna-

migrazione di un individuo proveniente da una delle altre specie presenti (con

à (1 n)

⇣

J n

J 1

⌘

) o dalla comparsa di una nuova specie (con probabilità n).

zionaria o di equilibrio P⇤(n) per la (3.1) è la seguente [8]

Ciascun nodo è un individuo rappresentato da un label che ne identifi

za. Denotiamo con C la collezione di tutti gli individui appartenenti a

~n = {n1, n2, . . . , nS} il vettore delle abbondanze per C, dove nj indica

della j-esima specie.

Ci poniamo nell’ensemble microcanonico, imponendo che ogni in

sostituito immediatamente da un altro della stessa o di un’altra specie

J =

S

Â

i=1

ni

La dinamica del mean field Voter Model a ogni istante di tempo è

selezionato casualmente muore e viene sostituito con un individuo di

probabilità n, mentre con probabilità 1 n il sito viene colonizzato d

presente su un nodo selezionato casualmente nella griglia. A differe

del Voter Model, dove l’interazione avveniva tra primi vicini, nel mode

con qualsiasi nodo della griglia, senza che però ci sia dispersione sulla

Il parametro n, detto diversification rate, gioca un ruolo fondamental

da che esso sia o meno nullo, la dinamica è completamente differente

parla di mean field Voter Model senza speciazione e in questo caso s

specie: in un tempo finito tutti i nodi saranno occupati da individui

popolazione dei votanti ha raggiunto un consenso). Se, invece, n > 0

Model con speciazione: in questo caso, in un tempo finito si raggiun

della distribuzione delle specie presenti.

P⇤

(n) = P(0)

n

’

z=1

b(z 1)

d(z)

(3.4)

e dedotta dalla condizione di normalizzazione

Â

n

P⇤

(n) = 1

esto risultato, imponiamo la condizione di equilibrio dP

dt (n, t) = 0 e notiamo

ere l’equazione come

I(n + 1) I(n) = 0 (3.5)

to

I(n) = d(n)P⇤

(n) b(n 1)P⇤

(n 1)

zione fisica che non si possa avere un numero di individui negativo, si ha che

quindi, I(0) = 0. Inoltre, supporre che quando una specie si estingue con-

na nuova la rimpiazza è equivalente a imporre condizioni al contorno riflet-

a ipotesi è ragionevole sulle scale temporali di nostro interesse. Sommando

otteniamo

1

[I(z + 1) I(z)] = I(n) I(0) = 0 =) I(n) = 0

La soluzione stazionaria o di equilibrio P⇤(n) per la (3.1) è la segue

P⇤

(n) = P(0)

n

’

z=1

b(z 1)

d(z)

dove P(0) può essere dedotta dalla condizione di normalizzazione

Â

n

P⇤

(n) = 1

Per arrivare a questo risultato, imponiamo la condizione di equ

che possiamo riscrivere l’equazione come

I(n + 1) I(n) = 0

dove abbiamo definito

I(n) = d(n)P⇤

(n) b(n 1)P⇤

(n 1

Imponendo la condizione fisica che non si possa avere un numero d

b( 1) = d(0) = 0 e, quindi, I(0) = 0. Inoltre, supporre che quan

temporaneamente una nuova la rimpiazza è equivalente a imporr

tenti alla (3.1): questa ipotesi è ragionevole sulle scale temporali d

Per arrivare a questo ri

che possiamo riscrivere l’e

dove abbiamo definito

Imponendo la condizione

b( 1) = d(0) = 0 e, quin

temporaneamente una nu

tenti alla (3.1): questa ipot

su tutti gli n la (3.5) ottenia

n 1

Â

z=0

[I(z +

da cui segue che P⇤(n) è ri

z=1

dove P(0) può essere dedotta dalla condizione di normali

Â

n

P⇤

(n) = 1

Per arrivare a questo risultato, imponiamo la condizio

che possiamo riscrivere l’equazione come

I(n + 1) I(n) = 0

dove abbiamo definito

I(n) = d(n)P⇤

(n) b(n 1)

Imponendo la condizione fisica che non si possa avere un

b( 1) = d(0) = 0 e, quindi, I(0) = 0. Inoltre, supporre c

temporaneamente una nuova la rimpiazza è equivalente

tenti alla (3.1): questa ipotesi è ragionevole sulle scale tem

su tutti gli n la (3.5) otteniamo

n 1

Â

z=0

[I(z + 1) I(z)] = I(n) I(0) = 0

e P(0) può essere dedotta dalla condizione di normalizzazione

Â

n

P⇤

(n) = 1

Per arrivare a questo risultato, imponiamo la condizione di equilibrio dP

dt (n, t) = 0 e notiamo

possiamo riscrivere l’equazione come

I(n + 1) I(n) = 0 (3.5

e abbiamo definito

I(n) = d(n)P⇤

(n) b(n 1)P⇤

(n 1)

onendo la condizione fisica che non si possa avere un numero di individui negativo, si ha che

1) = d(0) = 0 e, quindi, I(0) = 0. Inoltre, supporre che quando una specie si estingue con

poraneamente una nuova la rimpiazza è equivalente a imporre condizioni al contorno riflet

i alla (3.1): questa ipotesi è ragionevole sulle scale temporali di nostro interesse. Sommando

utti gli n la (3.5) otteniamo

n 1

Â

z=0

[I(z + 1) I(z)] = I(n) I(0) = 0 =) I(n) = 0

ui segue che P⇤(n) è ricorsiva, come si voleva: d(n)P⇤(n) = b(n 1)P⇤(n 1).

Â

n

P⇤

(n) = 1

niamo la condizione di equilibrio dP

dt (n, t) = 0 e notiamo

e

n + 1) I(n) = 0 (3.5)

)P⇤

(n) b(n 1)P⇤

(n 1)

si possa avere un numero di individui negativo, si ha che

noltre, supporre che quando una specie si estingue con-

za è equivalente a imporre condizioni al contorno riflet-

ole sulle scale temporali di nostro interesse. Sommando

I(n) I(0) = 0 =) I(n) = 0

si voleva: d(n)P⇤(n) = b(n 1)P⇤(n 1).

dP

dt

(n, t) = b(n 1) · P(n 1, t) [b(n) + d(n)] · P(n, t) + d(n + 1) ·

dove b(n) e d(n) sono rispettivamente i parametri di nascita e morte, dati dal

b(n) = (1 n) ·

n

J

J n

J 1

d(n) = (1 n) ·

n

J

J n

J 1

+ n ·

n

J

Notiamo che queste definizioni sono consistenti con le due regole della

Model:

• con probabilità 1 n si ha la morte di un individuo della comunità no

specie data (con probabilità J n

J ) accompagnata dalla nascita di un ind

scelta ( n

J 1 );

• con probabiltà n

J si ha la morte di un individuo appartenente alla specie

ta o dalla migrazione di un individuo proveniente da una delle altre s

probabilità (1 n)

⇣

J n

J 1

⌘

) o dalla comparsa di una nuova specie (con p

La soluzione stazionaria o di equilibrio P⇤(n) per la (3.1) è la seguente [8]

P⇤

(n) = P(0)

n

’

z=1

b(z 1)

d(z)

dove P(0) può essere dedotta dalla condizione di normalizzazione

Mapping birth-death ME with Voter Model: Analytical Solution

Birth rate

Death rate

BCCurrent of probability

Solution](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/udinesummerschool-suweis-180909213937/75/A-statistical-physics-approach-to-system-biology-27-2048.jpg)

![Connected components in a network

Laplacian matrix!

The Laplacian matrix is a similarly useful matrix defined by:!

L = K - A!

dΨ[t]/dt=-DLΨ[t]

Eigenvalues of L

Connected Compone](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/udinesummerschool-suweis-180909213937/75/A-statistical-physics-approach-to-system-biology-39-2048.jpg)

![y health

of com-

m patho-

nt (3–6).

s ecolog-

different

tends to

periods

for host

res that

unctions

espond-

ity com-

h (4, 13).

en char-

al work.

erstand-

rticular,

y. There

heory to

erns for

n made

dels (14)

ities (15).

y diverse

), which

llenging

ecology

dels that

rge and

develop

he gen-

where the types of interactions between species

are randomly distributed, meaning that +/+ (coop-

eration) and –/– (competition) interactions occur

with half the probability of +/– (exploitation) inter-

actions. Also, whereas ecological competition is

thought to be prevalent in natural microbial com-

munities (20), it is commonly assumed that the

functioning of microbiome communities restsupon

species that engage in cooperative metabolism (+/+)

potentialcommunitytypes,coveringthefullrangeof

possible interactions and species diversities [Fig. 1

and supplementary method 1 (31)]. We develop

our theory for unstructured ecological networks

because, unlike in plant-pollinator communities

or food webs (32, 33), there is no evidence of strong

structuring within microbial communities (16).

However, although no single structure type dom-

inates in these communities, our mathematics

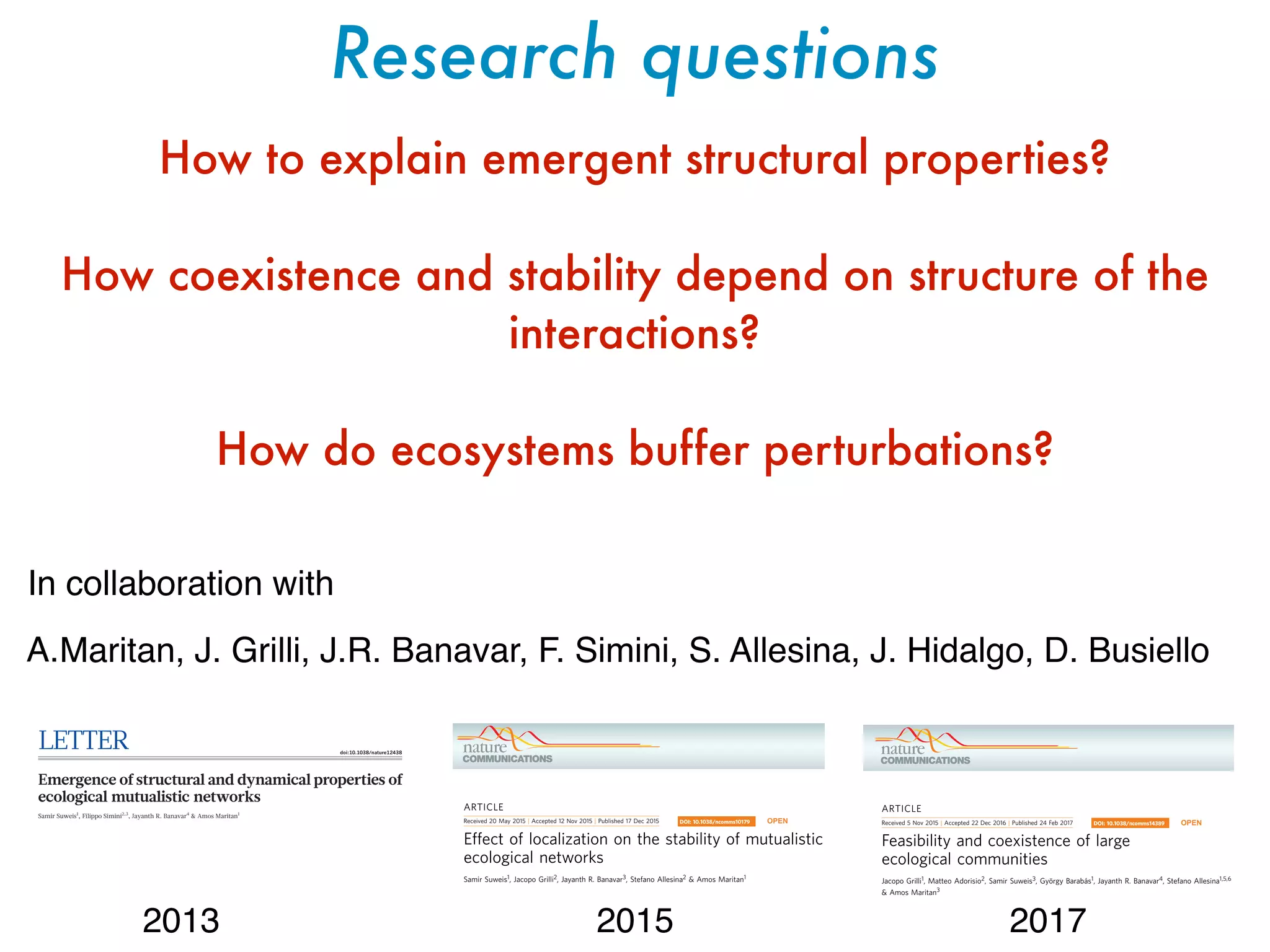

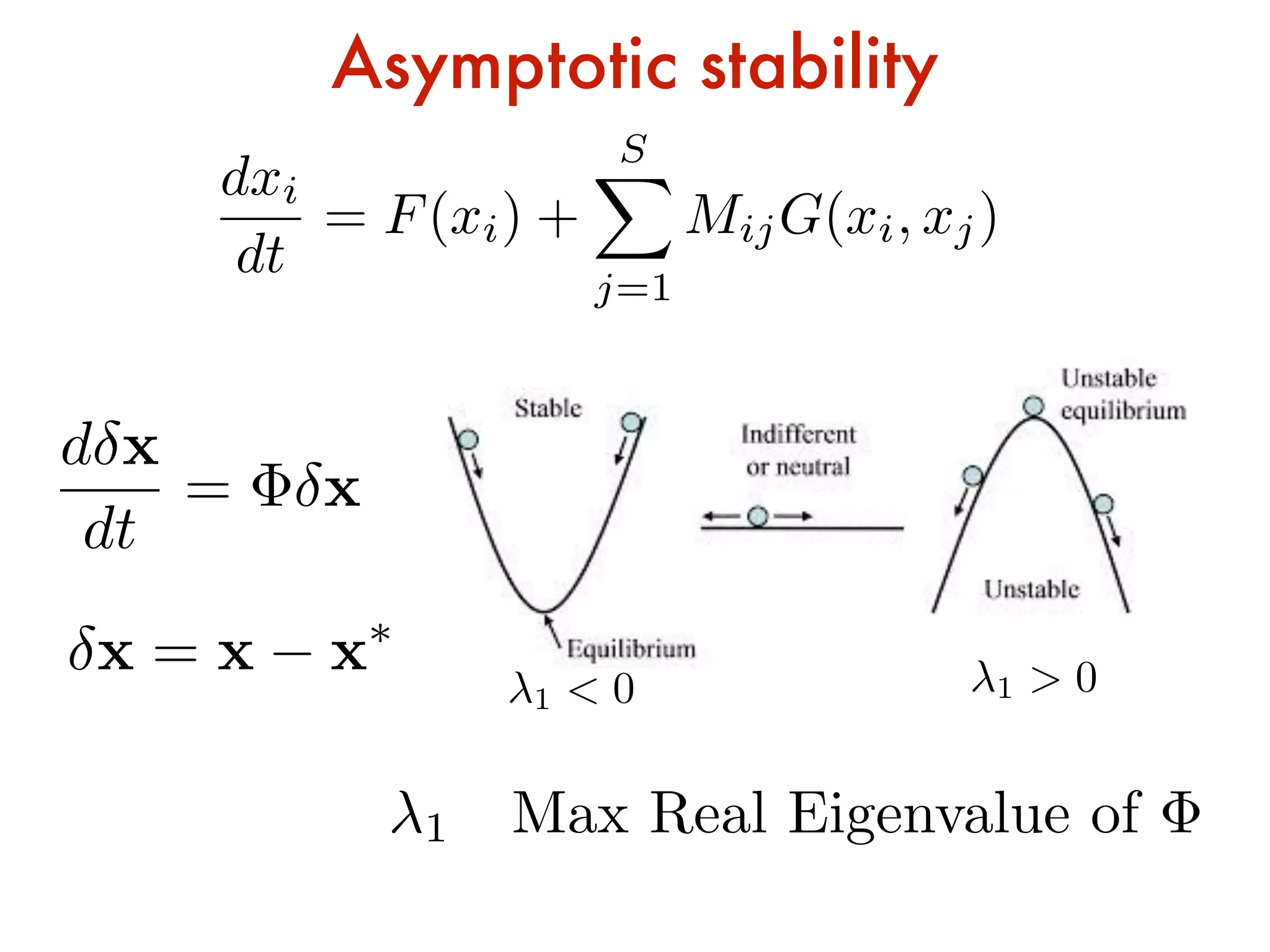

Fig. 1. Ecological theory and microbiota stability. (A) Ecological network theory captures networks of

microbial species that interact with themselves (–s) and other genotypes (aij). (B) Coupled ordinary differential

onNovemwww.sciencemag.orgDownloadedfromonNovemwww.sciencemag.orgDownloadedfromonNovemwww.sciencemag.orgDownloadedfromonNovemwww.sciencemag.orgDownloadedfrom

tion of cooperative interactions within communi-

ties nearly always decreases the overall return

rate and the likelihood of stability [Fig. 2 and

lysis, we find the same

is destabilizing. Howe

plementary materials

Fig. 2. Cooperation reduces community stability. (A) Illustration of changin

the proportion of cooperative links in networks. Pm, proportion of cooperative in

MICROBIOME

The ecology of the microbiome:

Networks, competition, and stability

Katharine Z. Coyte,1,2

* Jonas Schluter,1,2,3

*† Kevin R. Foster1,2

†

The human gut harbors a large and complex community of beneficial microbes that remain stable

over long periods.This stability is considered critical for good health but is poorly understood.

Here we develop a body of ecological theory to help us understand microbiome stability.

Although cooperating networks of microbes can be efficient, we find that they are often unstable.

Counterintuitively, this finding indicates that hosts can benefit from microbial competition when

this competition dampens cooperative networks and increases stability. More generally, stability is

promoted by limiting positive feedbacks and weakening ecological interactions.We have analyzed

host mechanisms for maintaining stability—including immune suppression, spatial structuring, and

feeding of community members—and support our key predictions with recent data.

T

he human microbiome contains hundreds

of species and trillions of cells that reside

predominantly in the gastrointestinal tract

(1, 2). These microbes provide many health

benefits, including the breakdown of com-

plex molecules in food, protection from patho-

gens, and healthy immune development (3–6).

The gut microbiome is often noted for its ecolog-

ical stability. Different people may carry different

microbial species, but any one individual tends to

carry the same key set of species for long periods

(6–8). This stability is considered critical for host

Seminal work by May suggests that species di-

versity can be problematic for community stability

(17, 19). However, May’s work focused on networks

where the types of interactions between species

are randomly distributed, meaning that +/+ (coop-

eration) and –/– (competition) interactions occur

with half the probability of +/– (exploitation) inter-

actions. Also, whereas ecological competition is

thought to be prevalent in natural microbial com-

munities (20), it is commonly assumed that the

functioning of microbiome communities restsupon

species that engage in cooperative metabolism (+/+)

and

The

Com

num

tera

anti

coop

prod

ly re

olism

alth

tent

ecol

T

biom

fects

with

crob

ics. T

of th

subs

gene

pote

poss

and

our

beca

or fo

stru

How

inat](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/udinesummerschool-suweis-180909213937/75/A-statistical-physics-approach-to-system-biology-42-2048.jpg)

![Why do physicists care ?

PPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

50 100 200 500

0.02

0.05

0.10

0.20

0.50

Number of Species [S]

Connectance[CΓ

]

C~1/S](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/udinesummerschool-suweis-180909213937/75/A-statistical-physics-approach-to-system-biology-50-2048.jpg)

![Why this recurrent topological properties?

Optimization Principles to explain

emergent patterns

UPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

50 100 200 500

0.02

0.05

0.10

0.20

0.50

Number of Species [S]

Connectance[CΓ

]

e S1: Best fit (red solid line) of the connectivity as a function of the number of

es for 56 mutualistic communities. Dashed gray lines represent the region within

±1 standard deviation confidence interval for the exponent estimate. The plot is in

g scale.

C~1/S

Busiello et al., Scientific Report

The Origin of Sparsity in the Interaction Networks of Living Systems

This talk](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/udinesummerschool-suweis-180909213937/75/A-statistical-physics-approach-to-system-biology-54-2048.jpg)

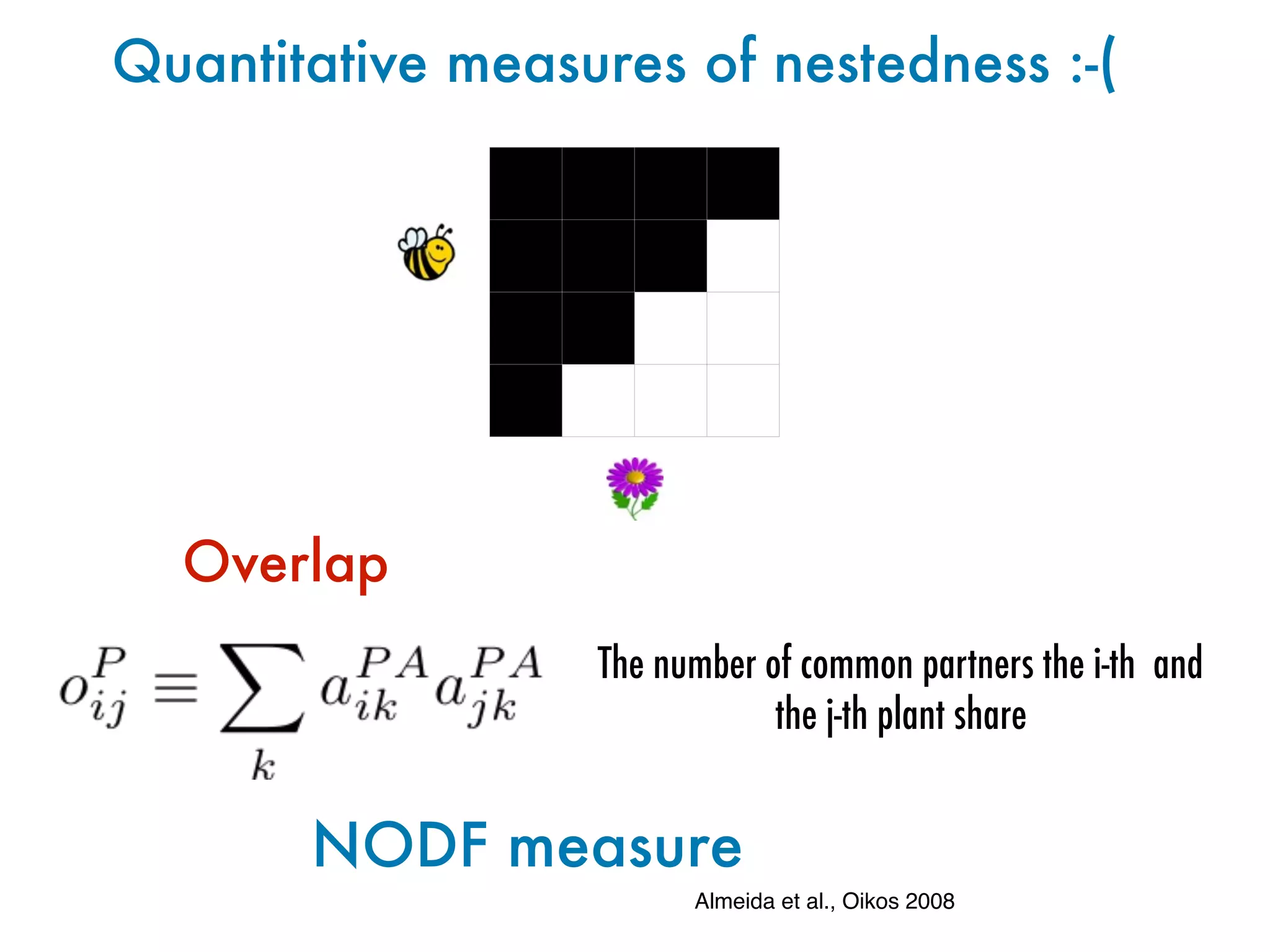

![Network data vs Randomization 1

Null model 1: we keep fixed S and C,

and place at random the edges

# Species [S]

Nestedness[NODF]

20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160 180 200

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

Random

Data](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/udinesummerschool-suweis-180909213937/75/A-statistical-physics-approach-to-system-biology-57-2048.jpg)

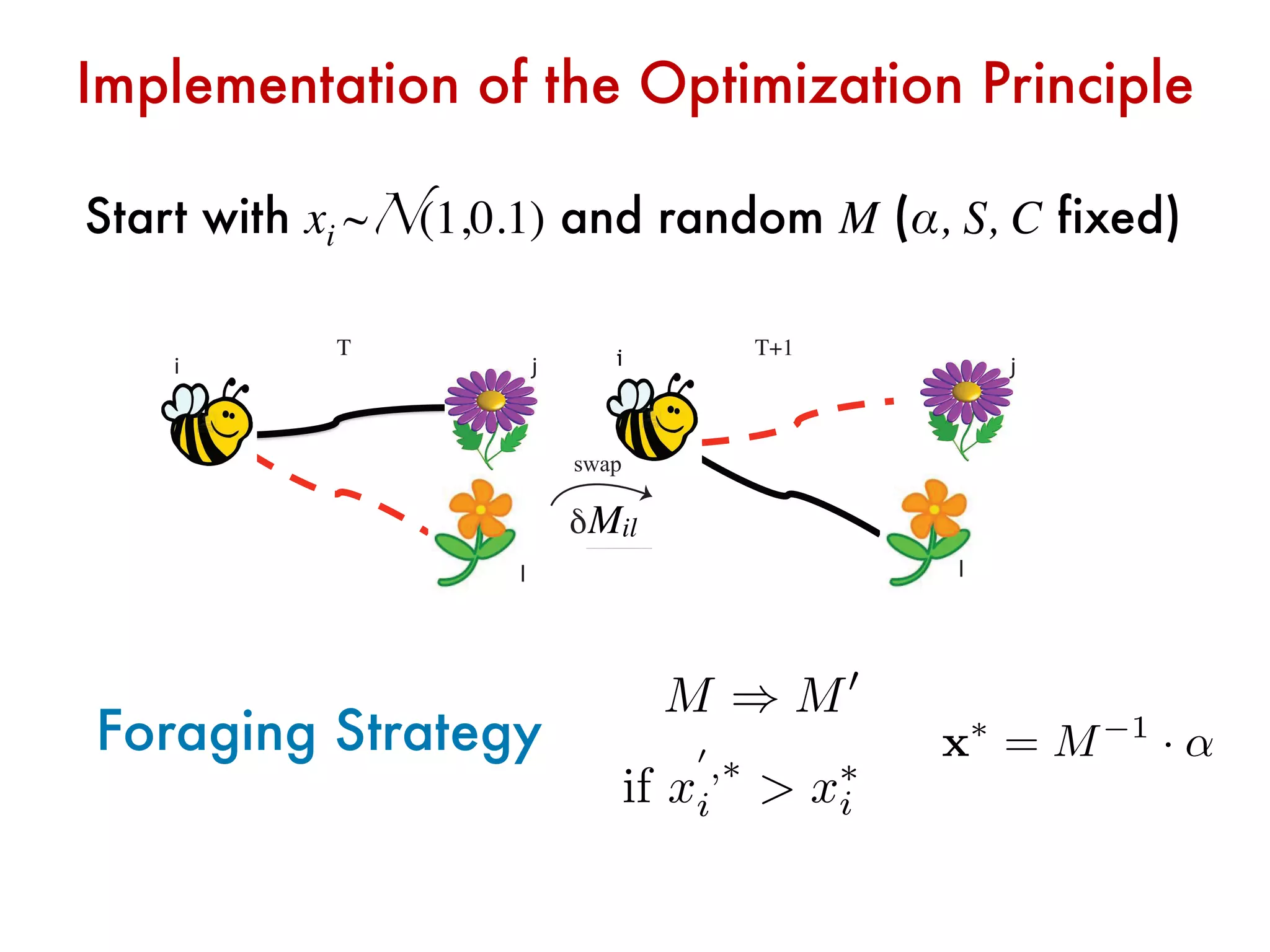

![Relation between sigle species and total abundance

i

li

j

|γij

|=0.0017

|γij

|=0

T=n

i

li

j

|γij

|=0.0017

|γij

|=0

T=n+1

swap

0.803522

1.08178

1.05803

1.05014

0.977939

1.01422

0.958128

1.13397

1.04078

1.0356

0.9664

1.02013

1.00682

0.67361

1.10131

1.07571

1.10289

0.959658

0.996913

0.918892

1.15298

1.03813

1.0223

1.01314

0.958794

1.00217

::

x* = x* =

T T+1

i j

l

k j

l

swap

δWilMil

x⇤

= M 1

· ↵

���� �����

����������[��]

Suweis et al., Nature 2013](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/udinesummerschool-suweis-180909213937/75/A-statistical-physics-approach-to-system-biology-72-2048.jpg)

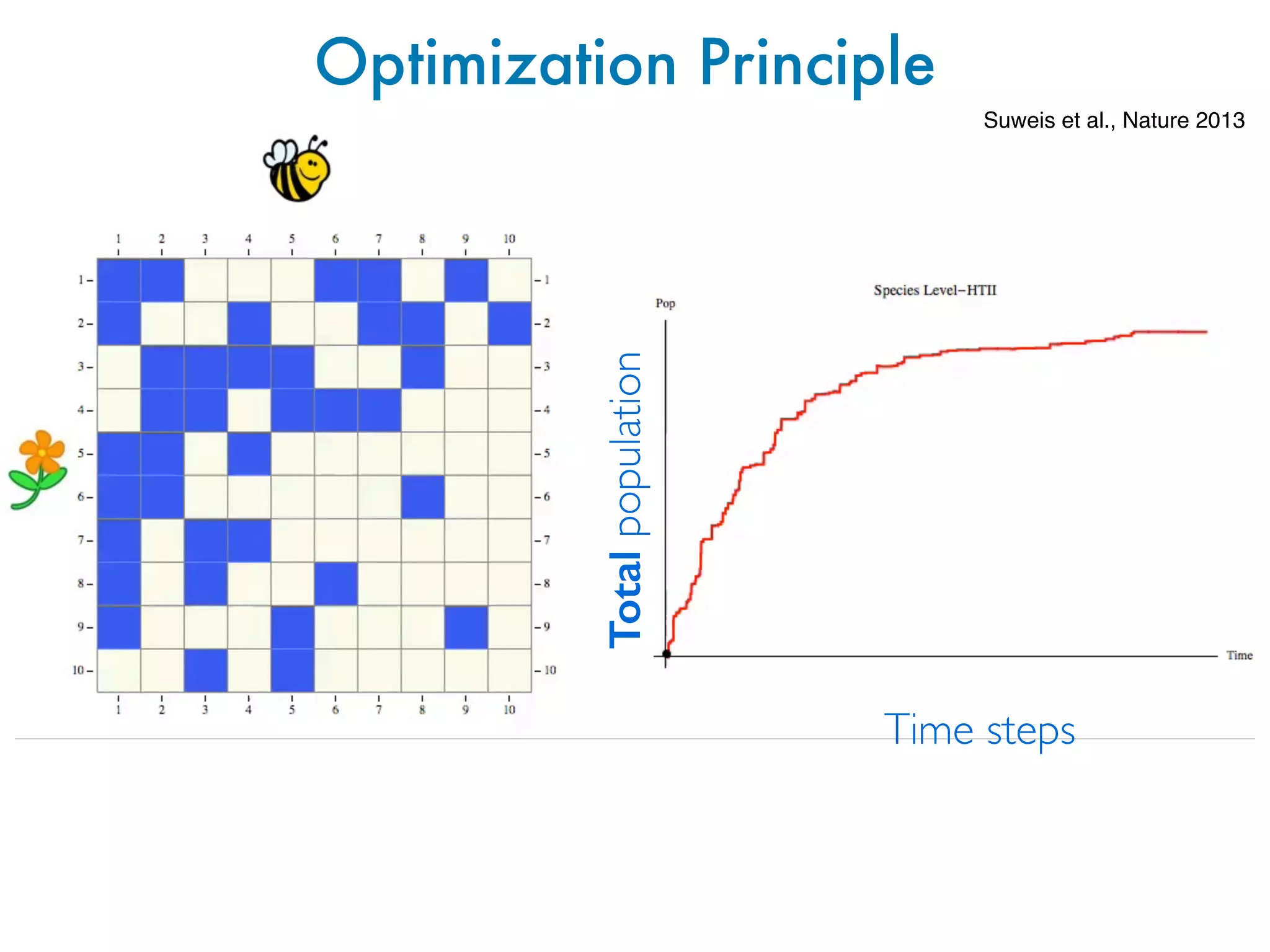

![Overlap and community abundance are correlated!

M = M0 + V =

I + ⌦ O

O I + ⌦

+

O

T

O

xtot

= K + Co ) o / C 1

xtot

+ constant

0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8

50

54

58

62

66

Nestedness [NODF]

Abundance[x]

C

ij =

⇢

with probability C ( > 0)

0 with probability 1 C

⌦ij = C!(1 ij) ! > 0

x⇤

= M 1

· ↵

Suweis et al., Nature 2013

x⇤

= M 1

· ↵ x⇤

+ x⇤

= (M + M) 1

· ↵

0 200 400 600 800 100012001400160018002000

9.8

10

10.2

10.4

10.6

10.8

11

11.2

11.4

11.6

11.8

STEPS [T]

Population

0 200 400 600 800 100012001400160018002000

9.8

10

10.2

10.4

10.6

10.8

11

11.2

11.4

11.6

11.8

STEPS [T]

Population

Averaged over 100 realizations

0 200 400 600 800 100012001400160018002000

19.5

20

20.5

21

21.5

22

22.5

STEPS [T]

TotoalPopulation

mean

1 realiz

if x⇤

k > 0 ) x⇤

tot > 0

Cooperation in nested mutualistic community!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/udinesummerschool-suweis-180909213937/75/A-statistical-physics-approach-to-system-biology-73-2048.jpg)

![# Species [S]

Nestedness[NODF]

σΓ

=0.0025

σΓ

=0.05

20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160 180 200

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

Random σΓ

=0.025

DataA

Suweis et al., Nature 2013](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/udinesummerschool-suweis-180909213937/75/A-statistical-physics-approach-to-system-biology-74-2048.jpg)

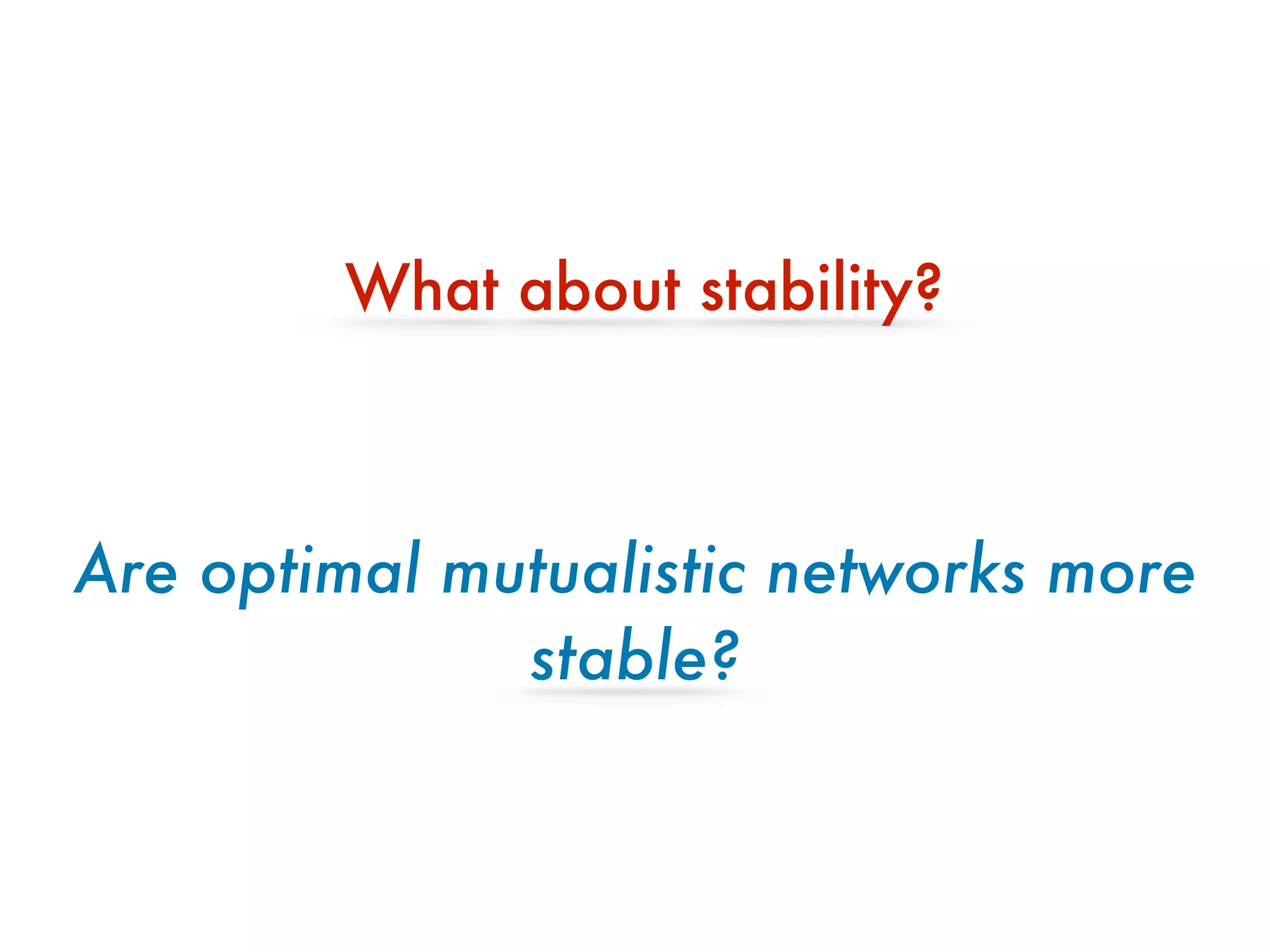

![No! Optimal networks are less resilient

c

−0.05 −0.04 −0.03 −0.02 −0.01 0

0

0.01

0.02

0.03

0.04

0.05

Max[Re(λ)]RarestSpecies[x]

b

R2

=0.999

0 5 10 15 20 25

0

1

2

3

4

5

number of connections [k]

speciesabundance‹x›

si

=|∑j

γij

|

a

‹x›

pdf

Max[Re(λ)]

0 1 2

5

0

4

3

2

1

-0.8 -0.7 -0.6 -0.5 -0.4 -0.3

5

10

15

20

25

Suweis et al., Nature 2013

A CB

time

perturbationstrength

λH reactivity

λ1 resilience

amplitude1

d x

dt

= J x

Jv1 = 1v1

u1J = 1u1

Suweis et al., in Nature Communications 2015

Beyond Resilience: Localization](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/udinesummerschool-suweis-180909213937/75/A-statistical-physics-approach-to-system-biology-76-2048.jpg)

![0 200 400 600 800

1

2

5

10

20

50

Size S

rIPRleft

0 200 400 600 800

1.0

10.0

5.0

2.0

3.0

1.5

15.0

7.0

Size S

rIPRright

A B

Ecological networks are localized!

A1 = |⇠0|(

X

j

v1,j|)2

Localization attenuates perturbations

Max|{v1}

A1 = 1/

p

S

Min|{v1}

A1 = i,j⇤

●

●●

●

●

●

●

●

●●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●●

●

●

●

●

●●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●●

●

●

●

●

●

■

■■

■

■

■

■

■

■■

■

■

■

■

■

■

■

■

■■

■

■

■■

■

■

■

■

■

■

■

■

■ ■■

■

■

■

■

■■

■

■

■

■

■

■

■

■

■

■

■

■

■

■

■

■

■

■

◆

◆

◆

◆◆

◆

◆

◆

◆

◆

◆

◆

◆

◆

◆

◆◆◆

◆◆

◆

◆

◆◆

◆

◆

◆

◆ ◆

◆

◆

◆

◆

◆

◆

◆

◆

◆

◆

◆◆

◆

◆

◆

◆

◆

◆

◆◆

◆

◆

◆

◆

◆◆

◆

◆

◆

◆

� ��� ��� ��� ���

���

���

���

���

���

���

���

���

���� [�]

/���

Trade Off with May!

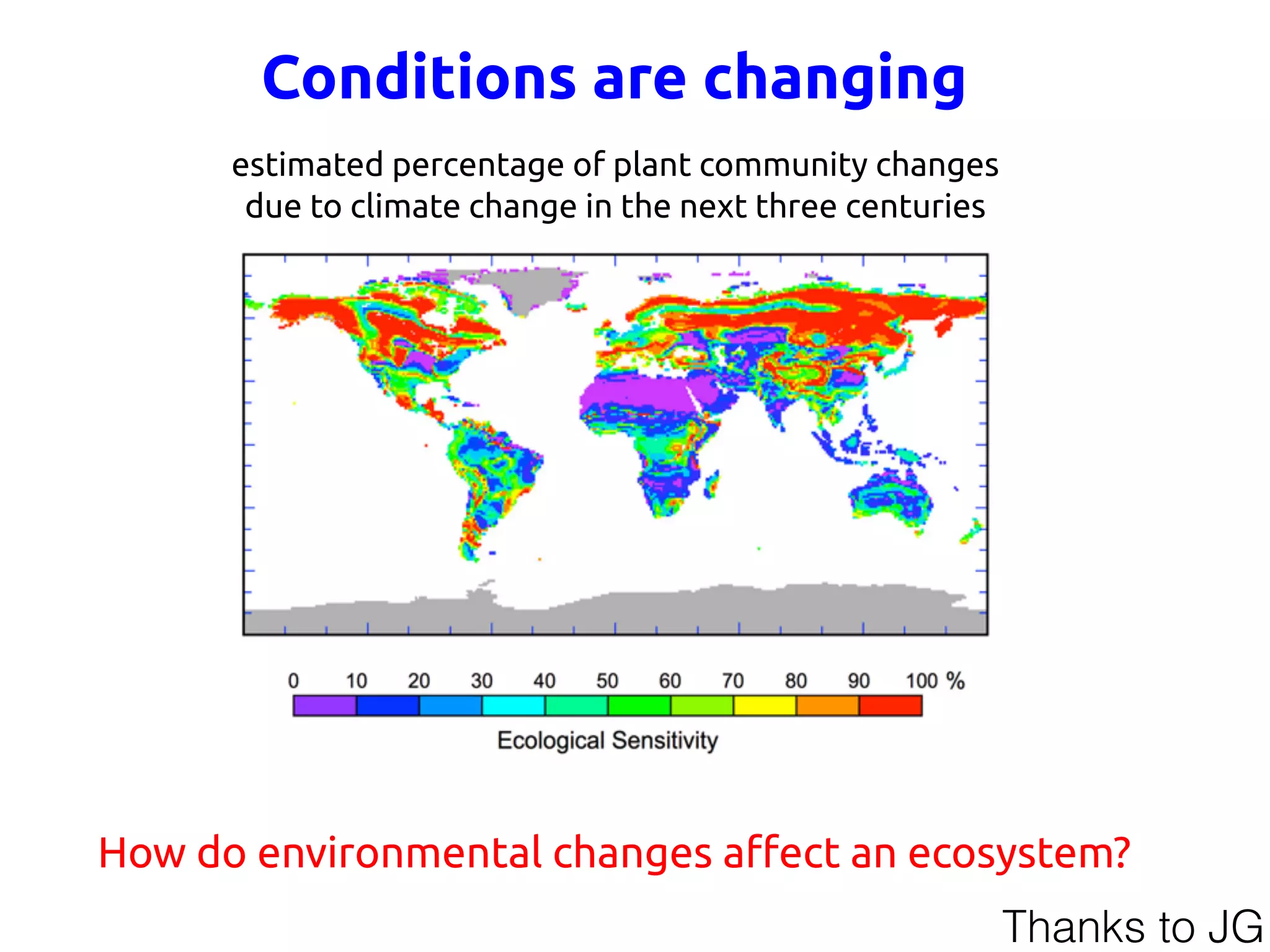

Suweis et al., in Nature Communications 2015](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/udinesummerschool-suweis-180909213937/75/A-statistical-physics-approach-to-system-biology-80-2048.jpg)

![Localization occurs on the hubs

Suweis et al., in Nature Communications 2015

1.0

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0 20 40 60

max=–0.27v1

u1

WH

s

smax

H=0.47

Species

TURE COMMUNICATIONS | DOI: 10.1038/ncomms10179

[| |]

#

#

Figure S33: Comparison between the histogram of all species degree and degree of lo-

calized species (✓ = 1.5/S) merging all the species in the 59 mutualistic networks (with

asymmetric interactions = 0.5).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/udinesummerschool-suweis-180909213937/75/A-statistical-physics-approach-to-system-biology-81-2048.jpg)

![Generalized Lotka-Volterra

intrinsic

growth rates

interaction

matrix

fixed point

how many combinations of growth rates

are compatible with coexistence?

What is the effect of the interaction matrix?

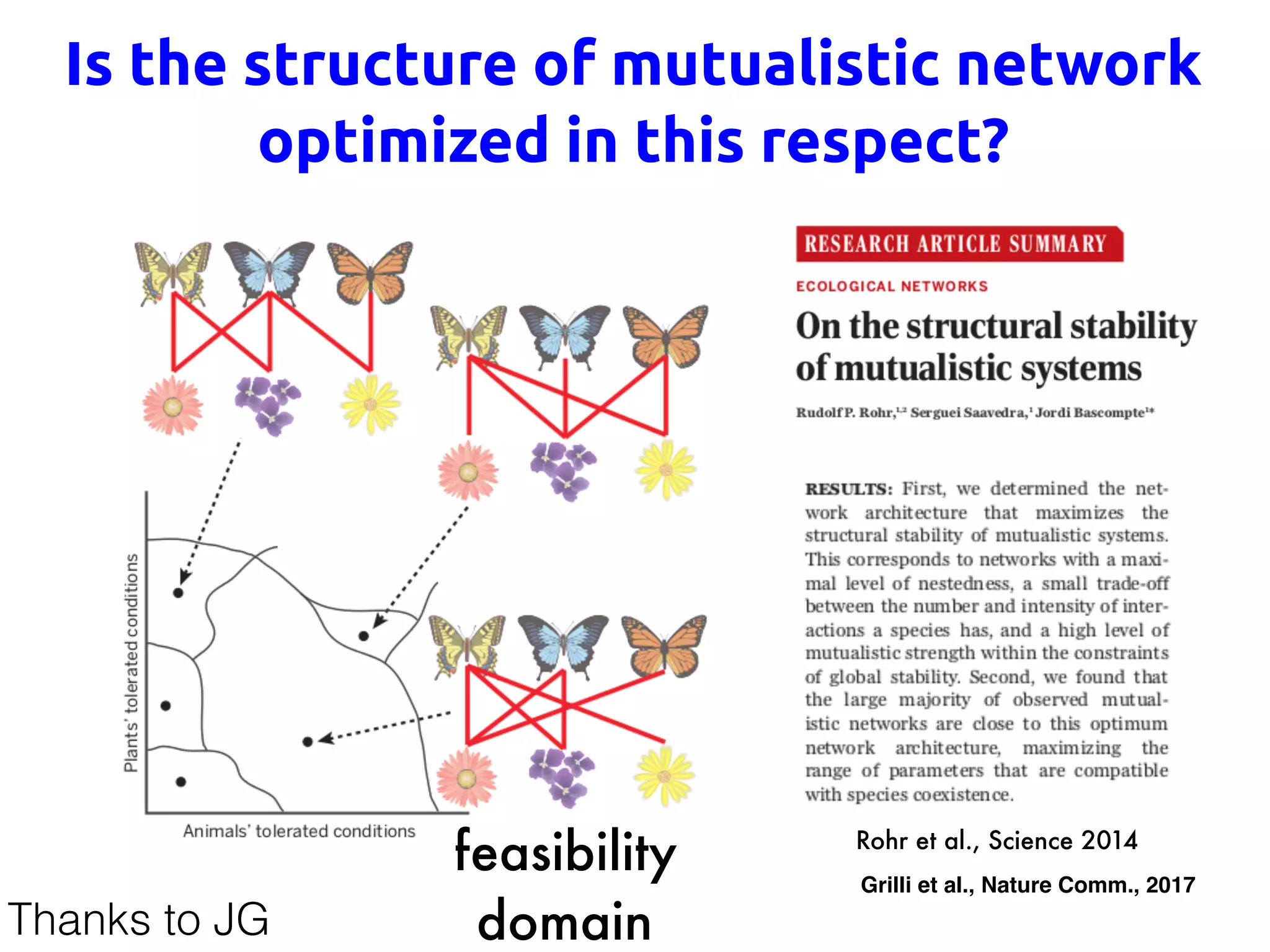

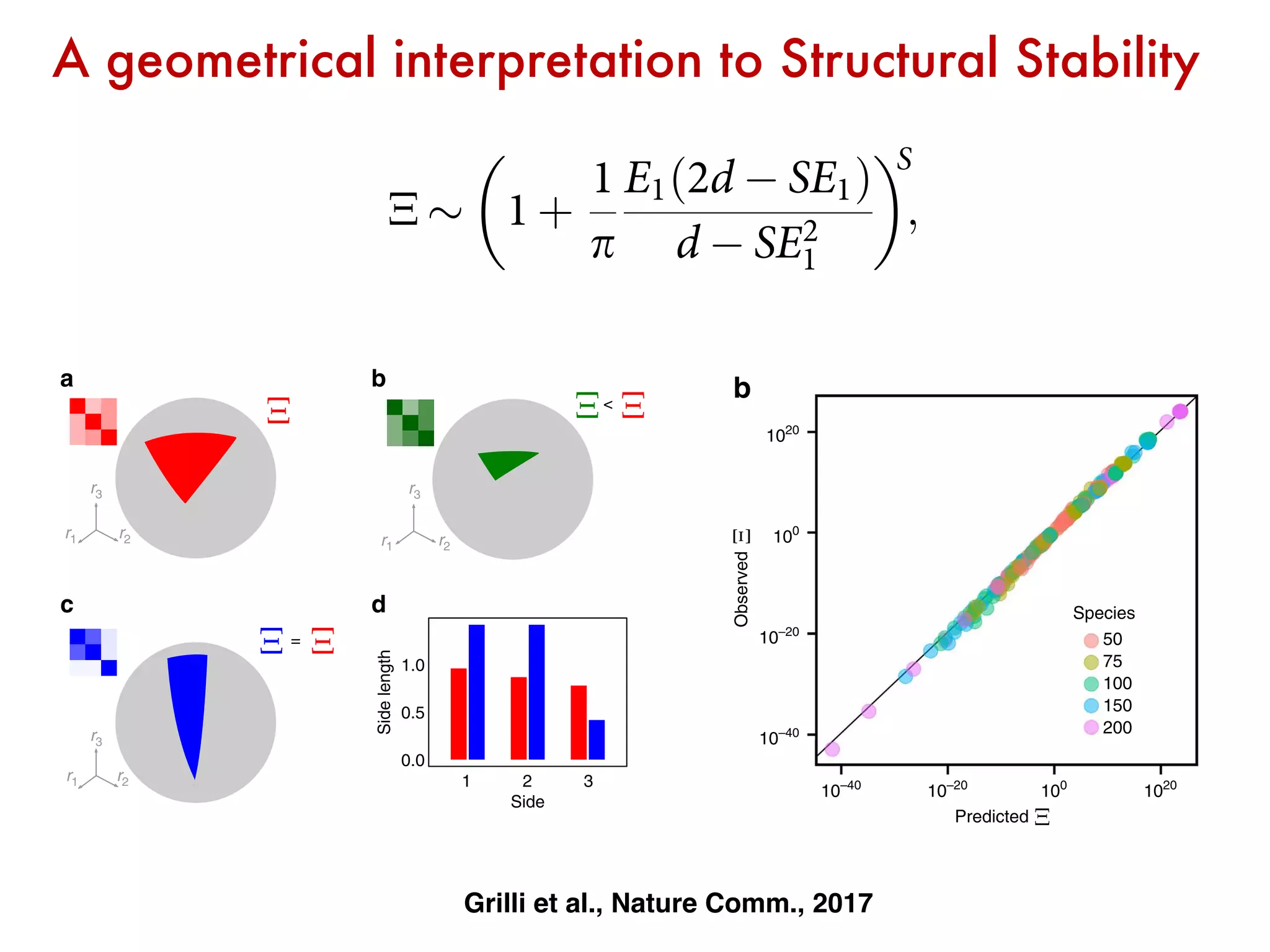

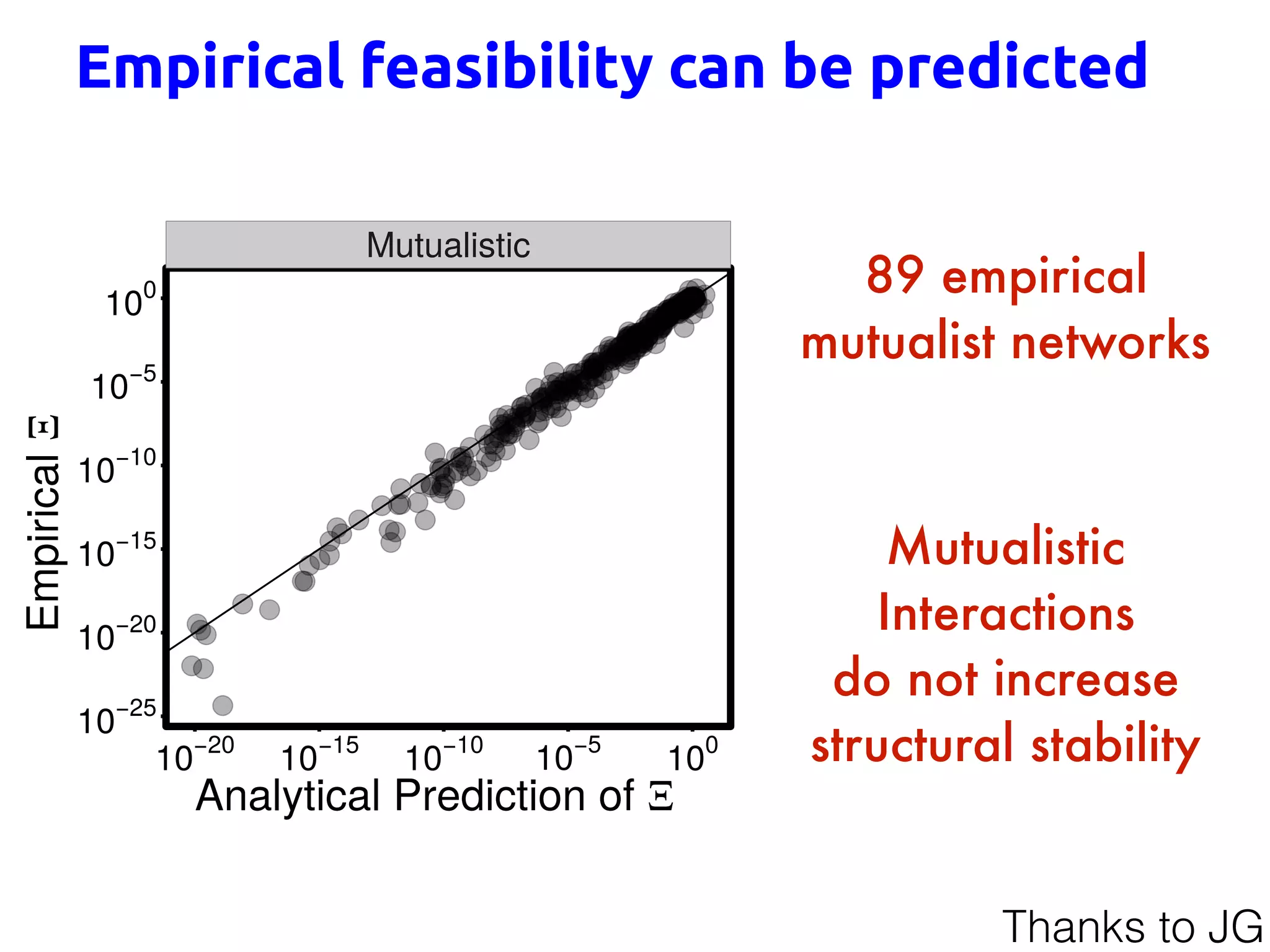

[Grilli, Adorisio, Suweis, Barabas, Banavar, Allesina and Maritan, 1507.05337]

Stable &

Feasible

(n>0)

Thanks to JG

-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/udinesummerschool-suweis-180909213937/75/A-statistical-physics-approach-to-system-biology-83-2048.jpg)

![Why this recurrent topological properties?

Optimization Principles to explain

emergent patterns

UPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

50 100 200 500

0.02

0.05

0.10

0.20

0.50

Number of Species [S]

Connectance[CΓ

]

e S1: Best fit (red solid line) of the connectivity as a function of the number of

es for 56 mutualistic communities. Dashed gray lines represent the region within

±1 standard deviation confidence interval for the exponent estimate. The plot is in

g scale.

C~1/S](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/udinesummerschool-suweis-180909213937/75/A-statistical-physics-approach-to-system-biology-87-2048.jpg)

![Network Connectivity [C]

Explorability[E]

Ability of living system to adapt and

explore new states

Trade-off stability-adaptability?

Explorability:

fixed C

Varying strengths W

volume of feasible

and stable x* the

dynamics can visit

M = TC ⇤ W(t)

C~1/S](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/udinesummerschool-suweis-180909213937/75/A-statistical-physics-approach-to-system-biology-88-2048.jpg)

![1 ⇠ SC

Explorability[E]

Asymptotic stability [Λ]

Morestable,lessexplorable

Less stable, less explorable

Less stable, more explorable

Optimizing

Explorability

Optimizing Stability

Starting Random Networks

Increasing C

Optimal tree-like

Convergent Optimality

C~1/S

Busiello et al. Sci. Report 2017](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/udinesummerschool-suweis-180909213937/75/A-statistical-physics-approach-to-system-biology-89-2048.jpg)

![257

biomass[OD620]

time [hours]

0 10 20 30 40

0

0.05

0.1

0.15

0.2

on

ucts

Enterobacter

Raoultella

Citrobacter

Pseudomonas

Stenotrophomonas

44%

20%

26%

7%

3%

OD620nm

time [hours]

0 10 20 30

0.4

0.2

0.0

0.2% glucose

Enterobacter byproducts

Logistic fit

Citrobacter growth

r = 0.34

K = 0.35

M9 + Glucose

?

M9 + metabolic

byproducts

a b

c d

e

% change biomass after 24h

-40 0 40numberofcommunities

0

10

20

30

40

50

f

K

Pseudomonas Raoultella

EnterobacterCitrobacter

0.2% Glucose

Coexistence of bacteria species with 1 resource!

characterization of all dominant genera within a representative community (fig. S5).

1

2

3

4

5

6

inoculum

7

8

9

10

11

12

0

0

0.25

0.25

0.5

0.5

0.75

0.75

1

10

0.25

0.5

0.75

1

0

0

0.25

0.25

0.5

0.5

0.75

0.75

1

10

0.25

0.5

0.75

1

Enterobacteriaceae

Pseudomonadaceae Pseudomonadaceae

Otherfamilies

Otherfamilies

Enterobacteriaceae

Initial (t = 0) Final (t = 84)

a

Inoculate

growth

dilution

Cross feeding is

fundamental

for coexistence!

Goldford et al. BioArxiv 2017 - Emergent Simplicity](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/udinesummerschool-suweis-180909213937/75/A-statistical-physics-approach-to-system-biology-90-2048.jpg)