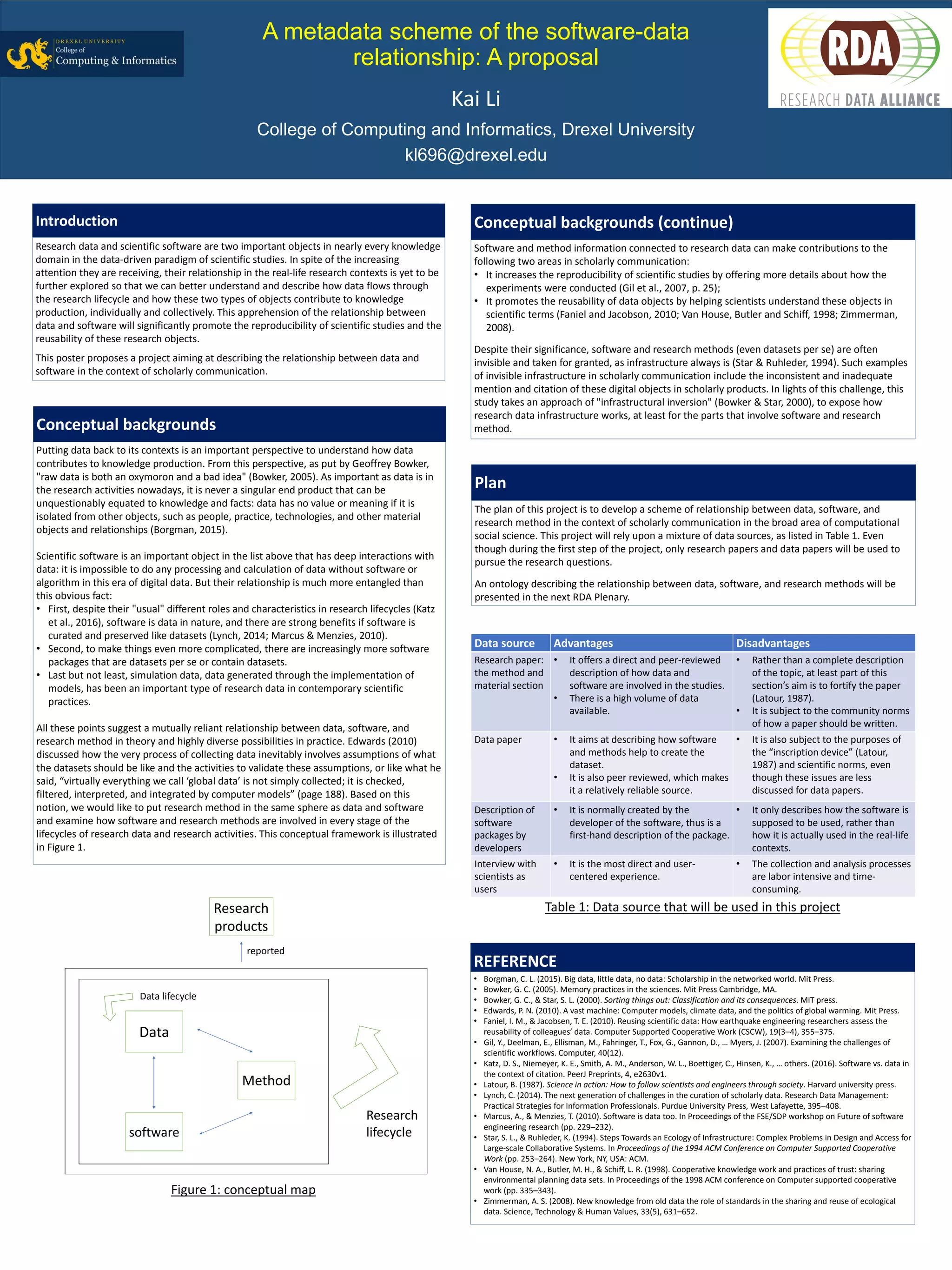

This document proposes developing a scheme to describe the relationship between research data, software, and methods. It argues that these elements are intertwined and influence each other throughout the research lifecycle. The goal is to increase reproducibility and reuse of digital research objects. To understand these relationships, the project will analyze research papers, data papers, software documentation, and interviews with scientists. An ontology will then be presented to formally represent how data, software, and methods interconnect in scholarly communication.