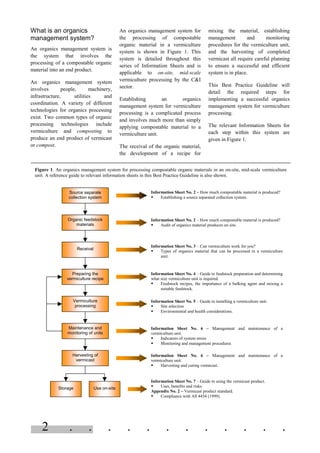

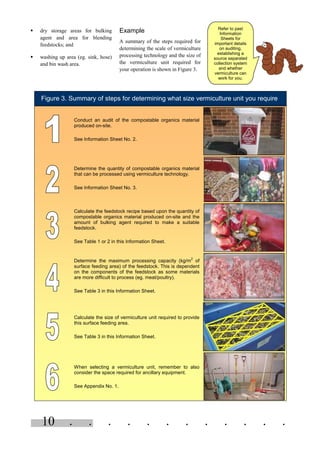

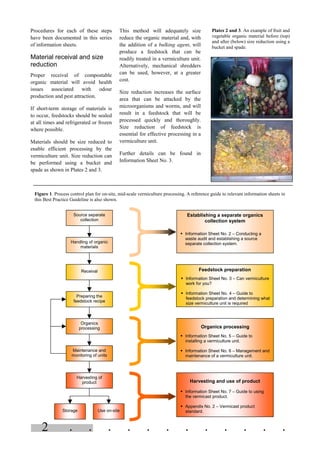

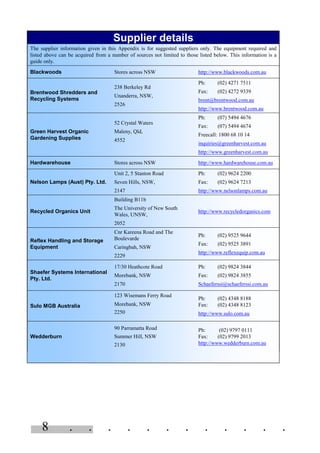

The document provides guidelines for managing on-site vermiculture technologies. It was published by the Recycled Organics Unit (ROU) in January 2002. The ROU is the NSW centre for organic resource management, information, research and development, demonstration and training. The guidelines contain 7 information sheets that provide details on establishing and managing an on-site vermiculture unit to process compostable organic waste for commercial and industrial organizations. The information sheets cover topics such as determining waste quantities, site selection, installation, operation, and end product use.